We’ve done quite a few posts over the years about old maps – we are both fascinated by them. So I’ve decided to draw all those posts together into a new Menu Page, so you can easily find any post you’re interested in.

Several posts went into detail about maps from the Elizabethan period. The Elizabethans were map-makers and they had a special interest in drawing up maps of Ireland – to confiscate tracts of land from the rebellious Irish and assign them to colonisers. Jobson was the cartographer who mapped Munster: two posts detail the maps drawn up for that purpose.

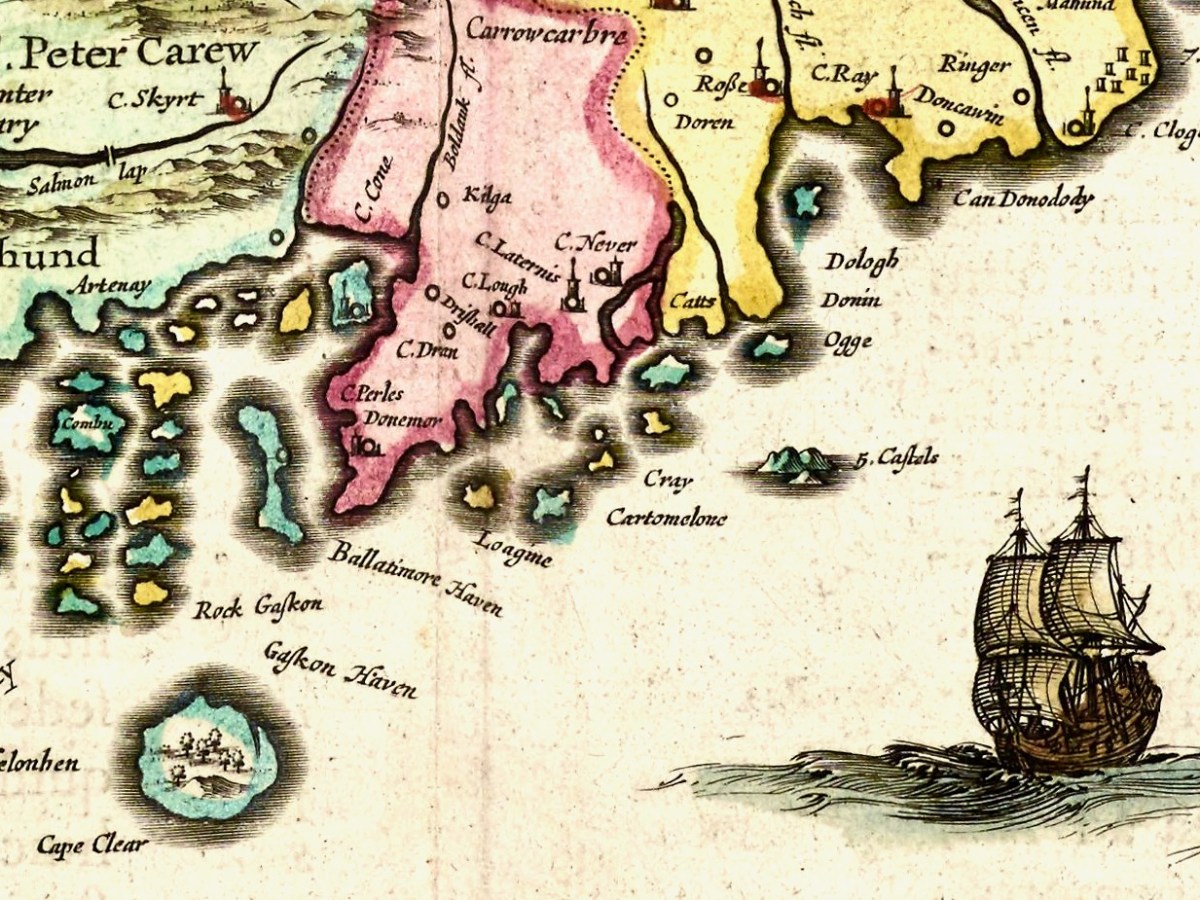

There’s a mysterious map in the British Public Record office – nobody knows who did it, but it was obviously done in the period following the Battle of Kinsale in 1601. While some of the elements are obvious, others are not, and pouring over a map like this raises as many questions as it answers. I titled the two posts Elizabethan Map of a Turbulent West Cork.

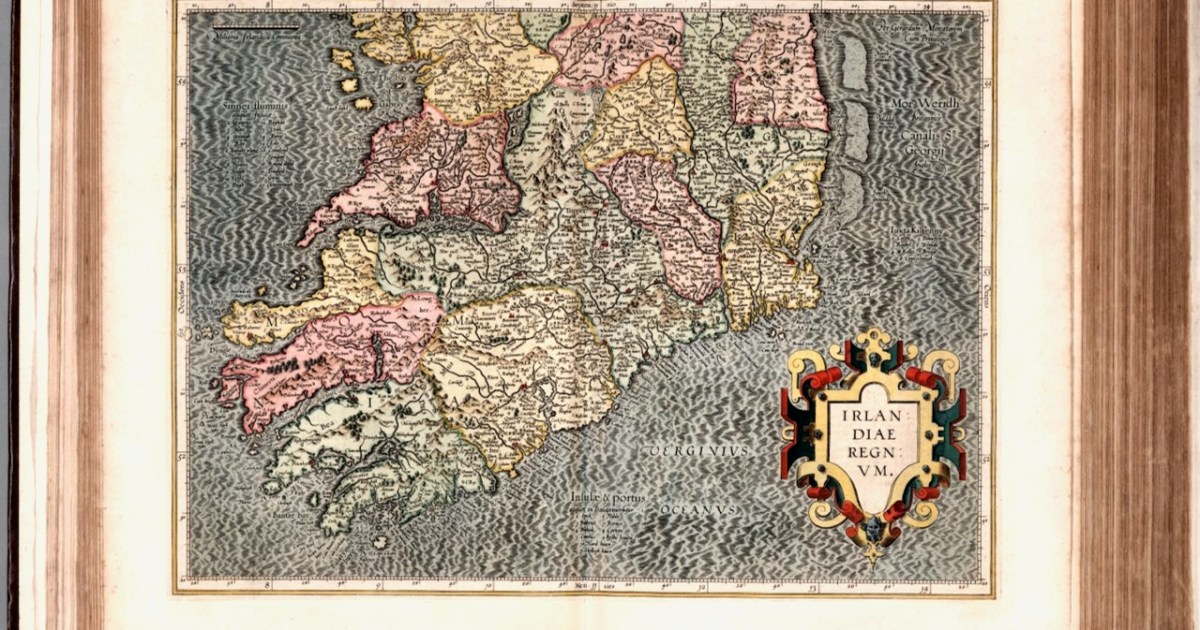

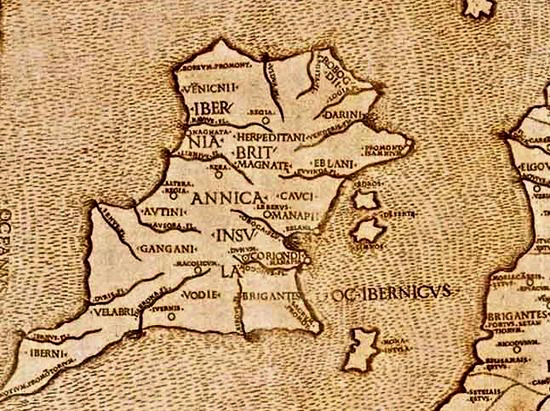

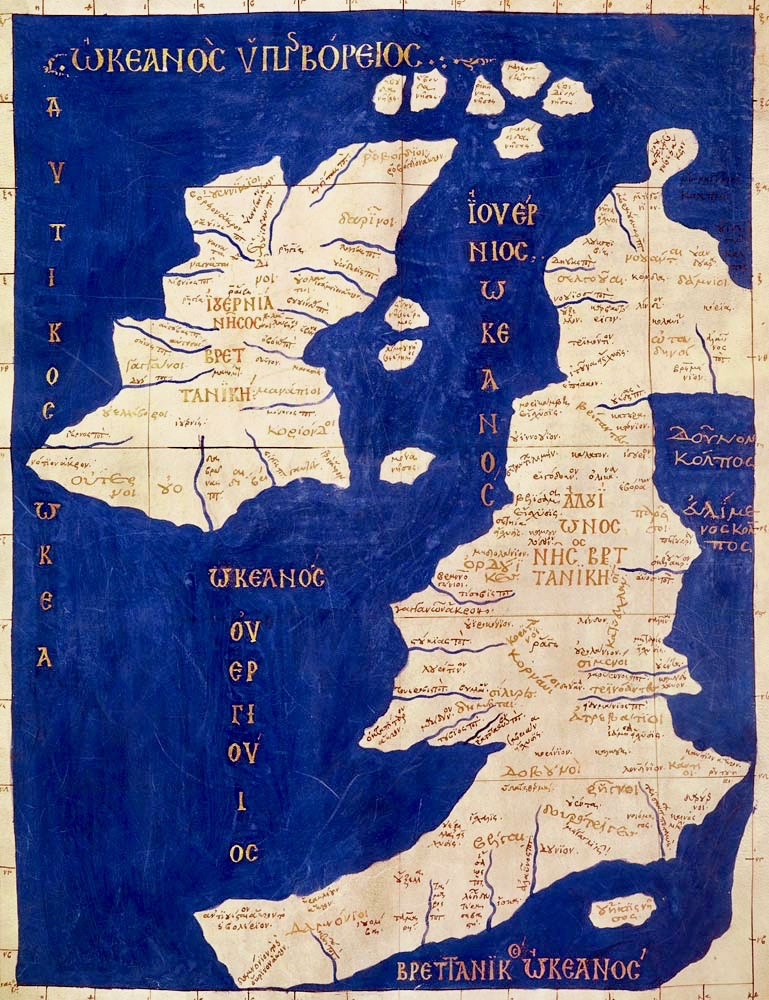

Two posts, Mapping West Cork, drew on maps from the David Rumsay Map Collection – a man who has done the world a great service by collecting and digitising maps from all over the world. These are very early maps by famous cartographers Mercator (done in the late 1500s) and Blaeu (from his 1655 Atlas). I’ve updated this post recently.

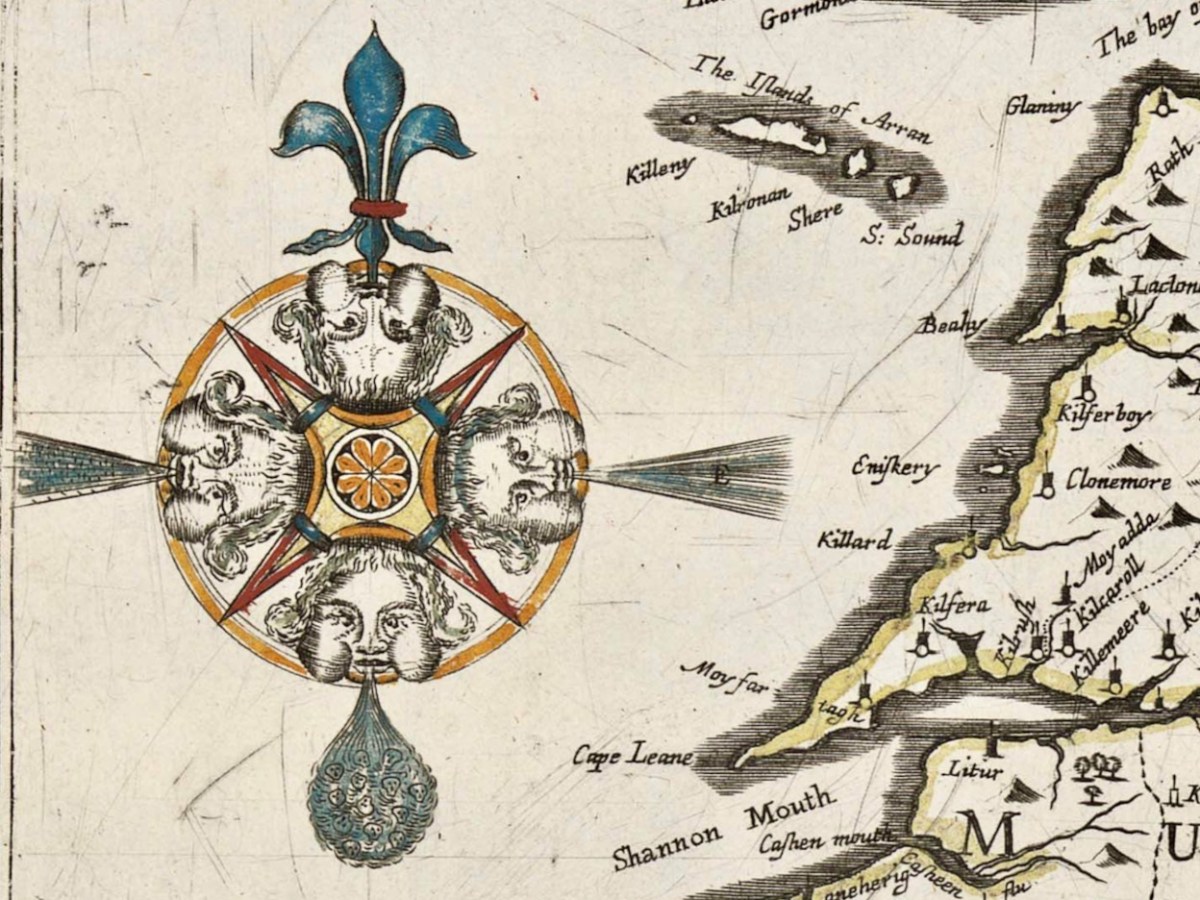

John Speed’s map, dating to 1611, although largely based on Mercator’s work, is more detailed and adds all kinds of interesting details about people and cities.

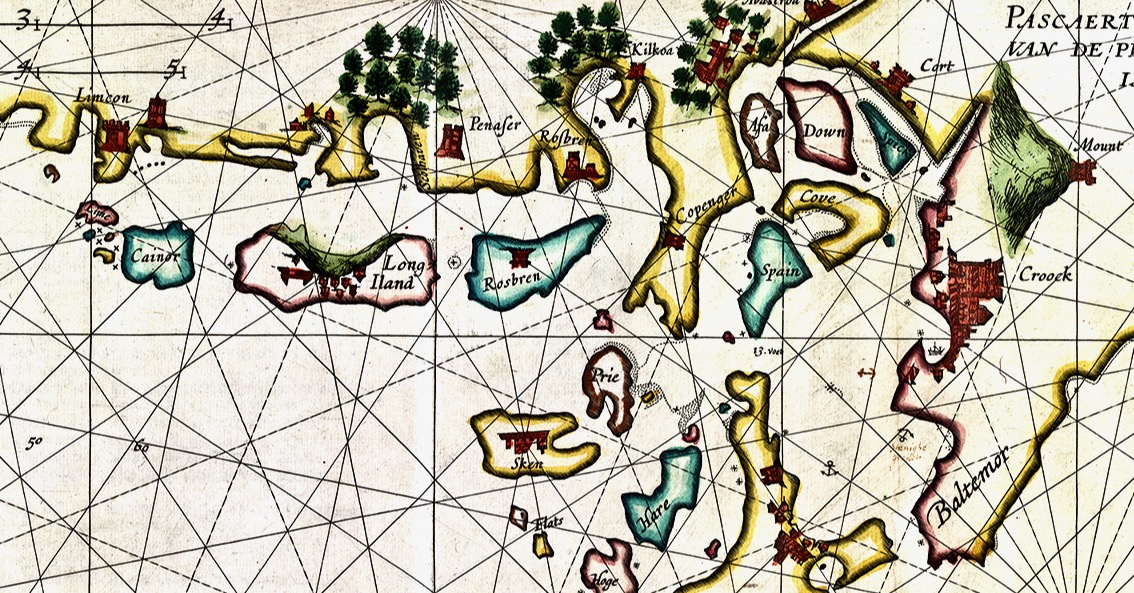

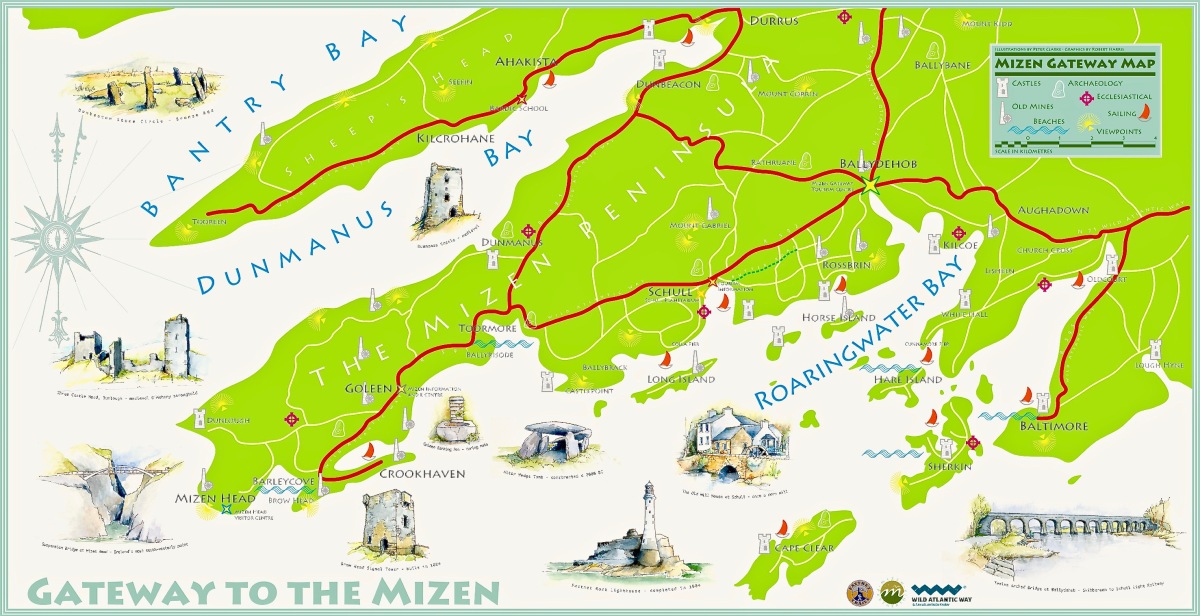

Robert’s post Roaringwater Bay in 1612 is about the Dutch Pirate Map. As he says in his post: The thing that sets the 1612 map apart, however, is that it was made in secret, and largely from surveys only carried out at sea. Also, it was specifically intended to enable a Dutch fleet to assail the pirate strongholds which became numerous around the area from Baltimore to Crookhaven, centred on Roaringwater Bay and ideal for forays into the wider Atlantic trade routes.

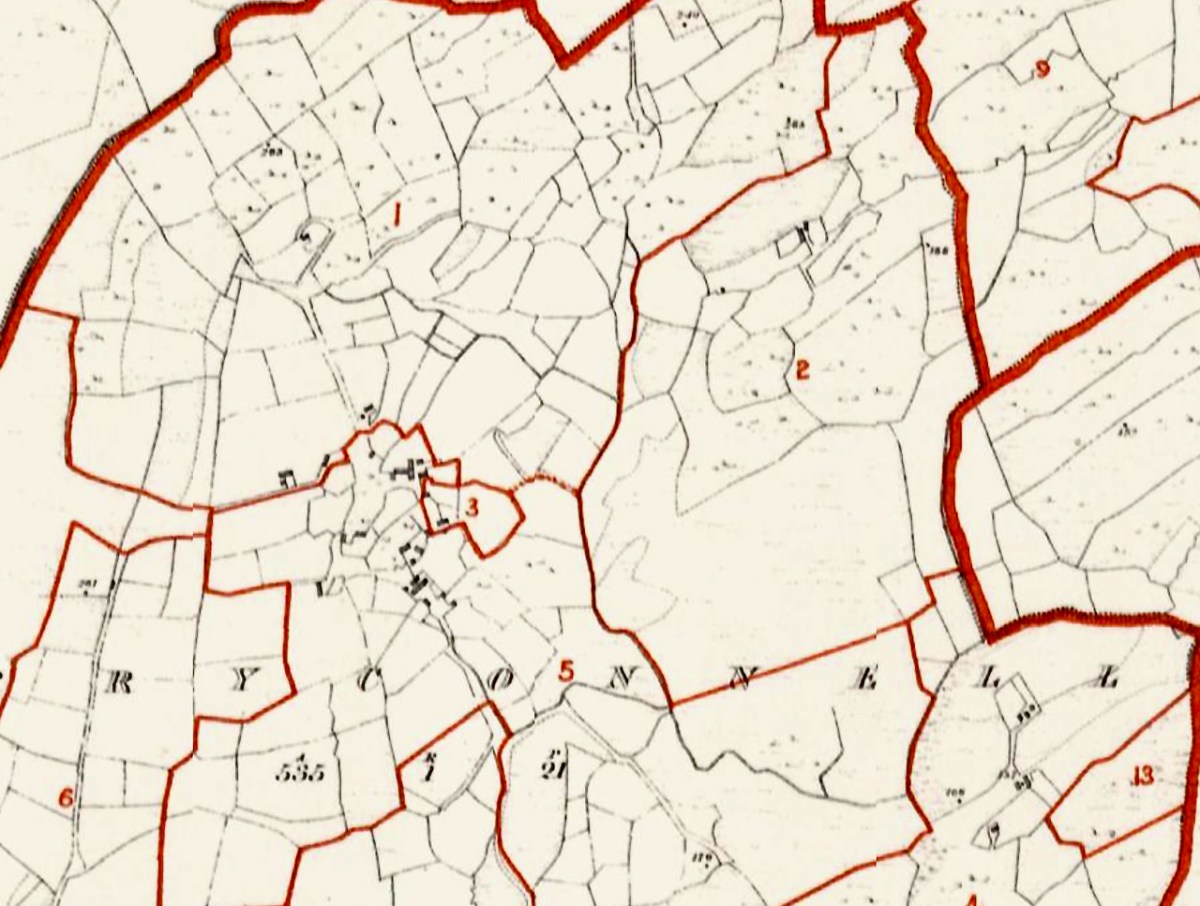

A series of three posts, all written by Robert, explored the world of the Down Survey – conducted by William Petty under the instructions of Oliver Cromwell, and like the Jobson maps, done for the purposes of assigning land to colonisers.

After an introductory post, Robert went into details about West Cork and then, in a third post, looked at Kerry. He is planning more in this series.

Finally, there’s Griffith’s Valuation – a series of detailed maps done by Sir Richard Griffith in the 19th century for the purpose of putting values on every square perch of land. Robert wrote about Griffith in The Rocky Road to Nowhere, and I used the Valuation in my post What the Forest Was Hiding.

We will update The Magic of Old Maps page as we write any new posts. I am leaving you with a new map – it’s the joint work of Robert and Peter Clarke, and the original hangs in the Bank House, Ballydehob’s Tourist Information Centre.

If you want to browse the David Rumsey map collection for yourself, it’s here.