We are often invited to join our friends Amanda and Peter Clarke on their journeys of exploration into the wild places of West Cork and Kerry. We even stray over into Limerick on occasion! And it’s usually all to do with Holy Wells. Amanda has been writing about them for years, and you can find her accounts of them in Holy Wells of Cork & Kerry, here.

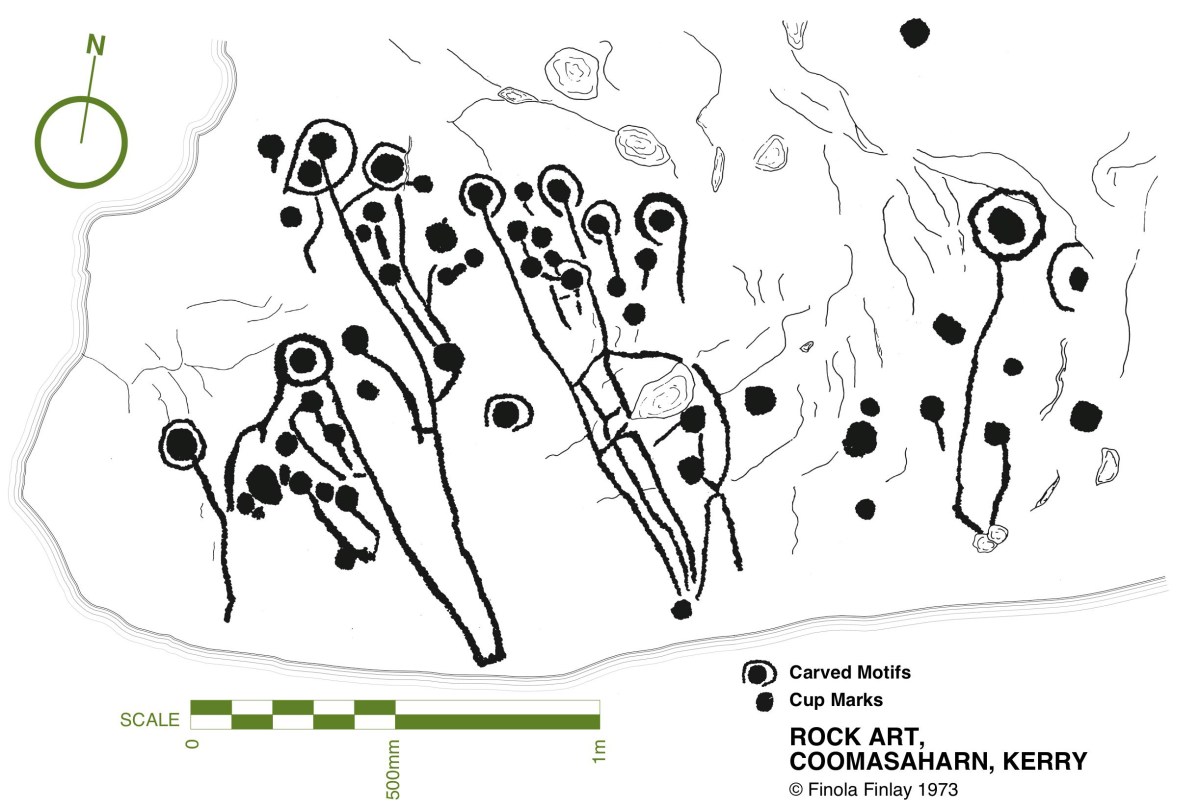

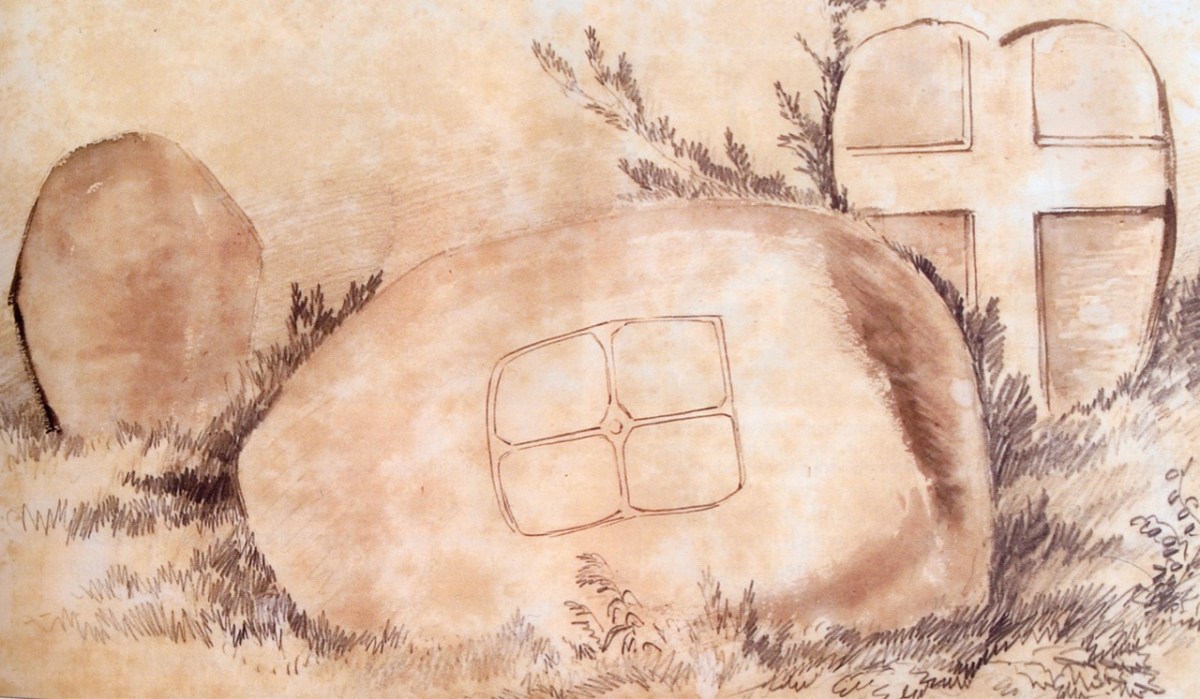

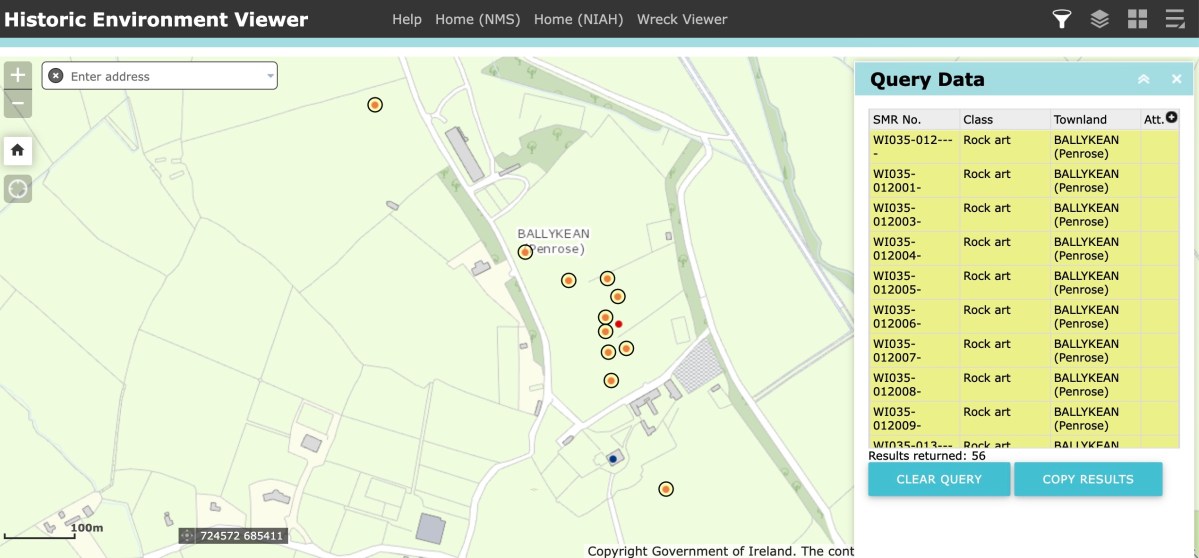

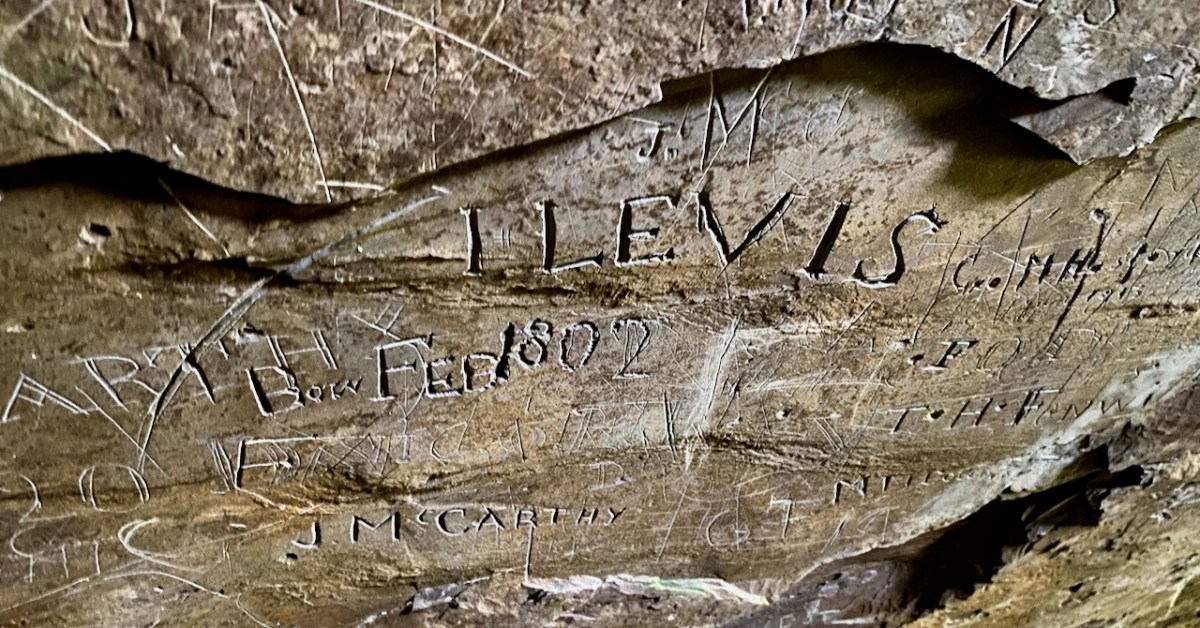

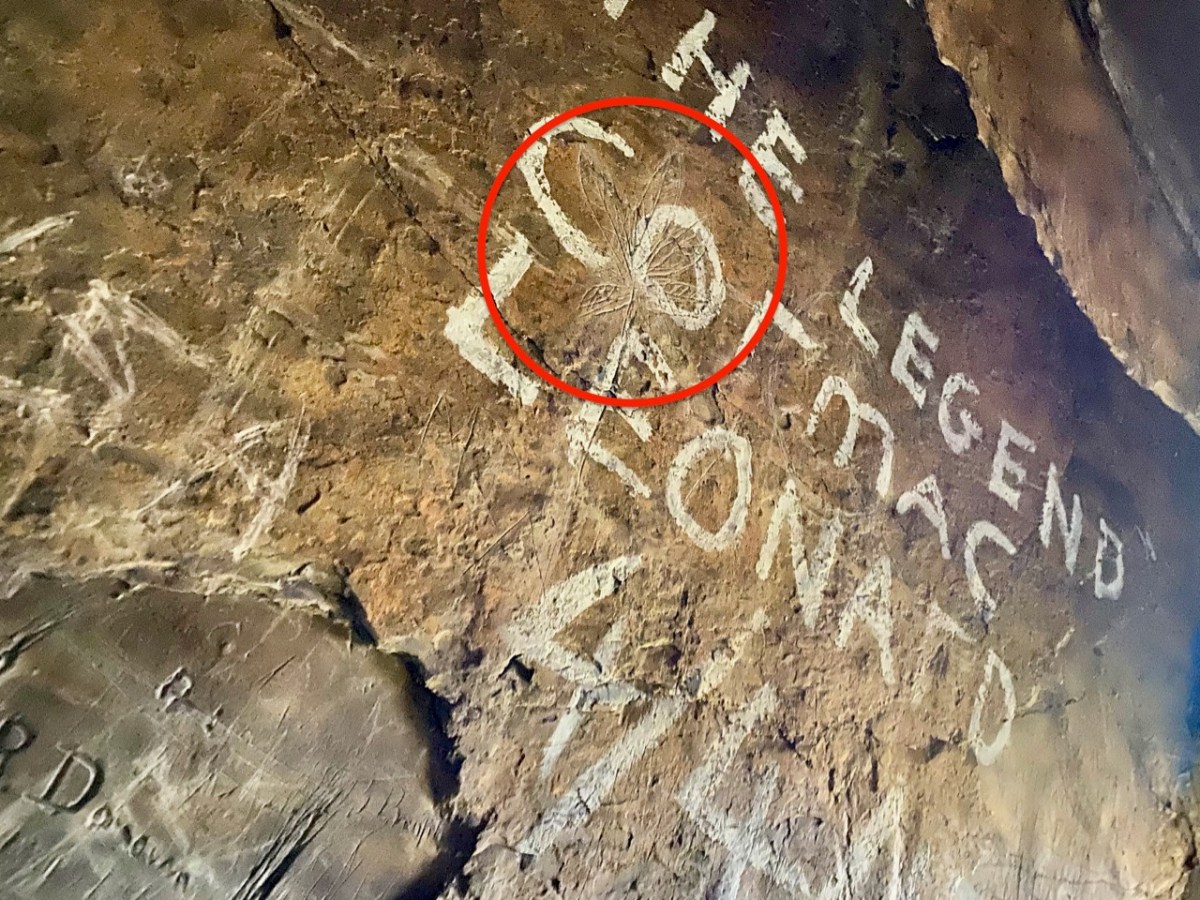

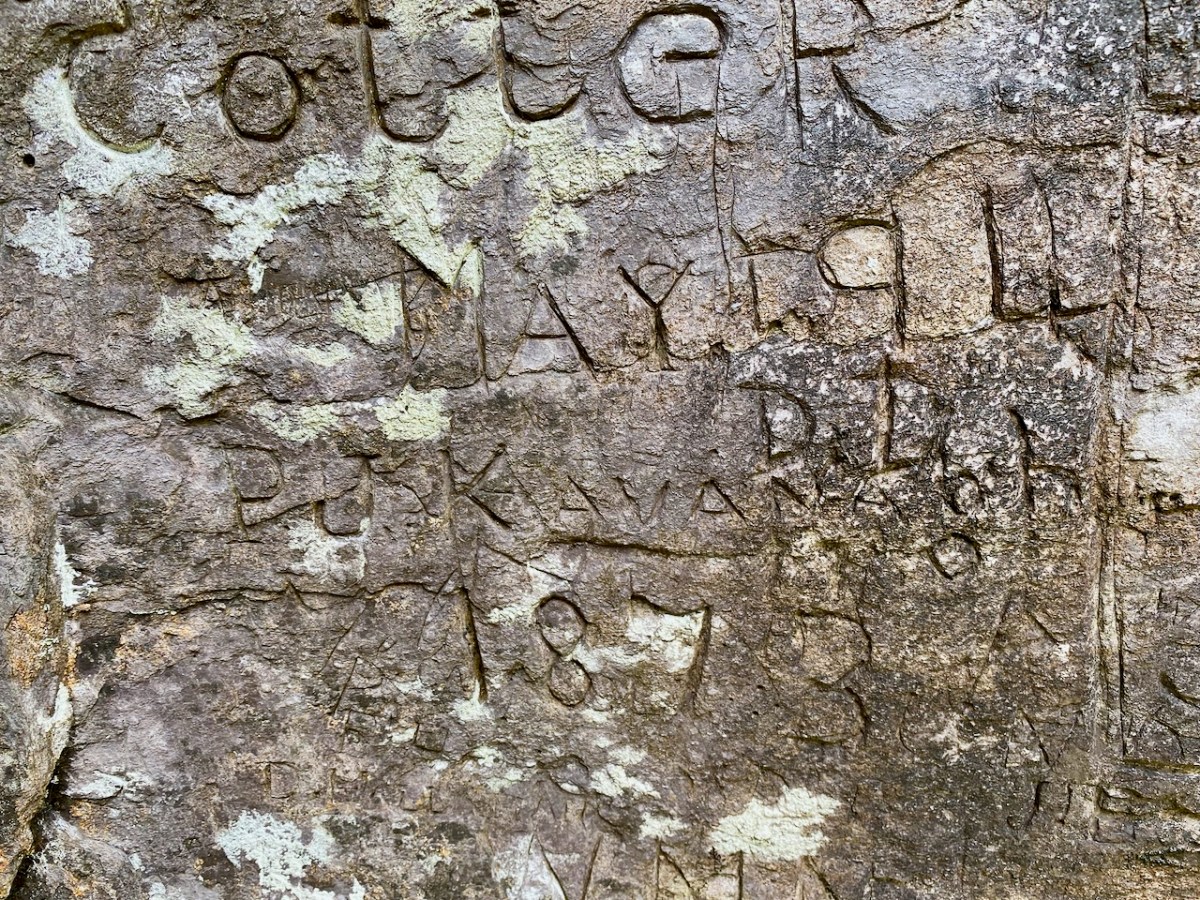

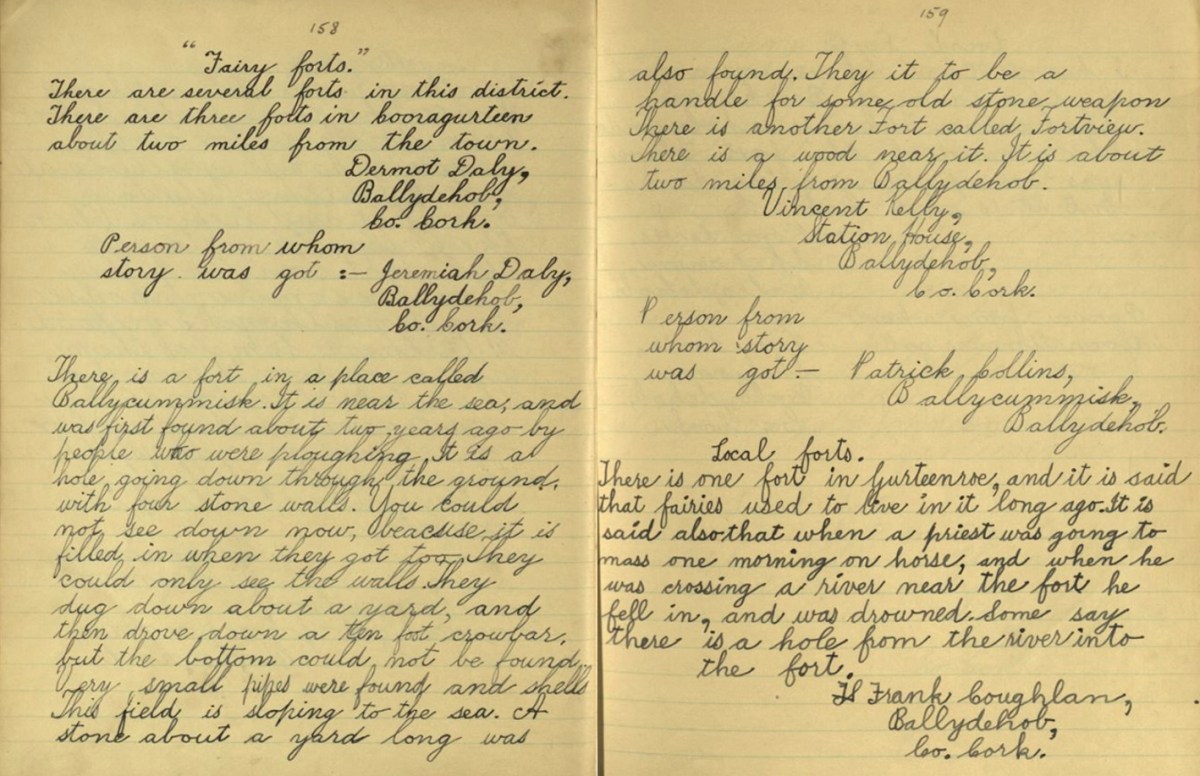

Recently we were at Loo Bridge, near Kilgarvan, Co Kerry. There’s a well there – Tobar na Naomh – All Saint’s Well, and there’s a lively account of it in the Dúchas Schools Folklore Collection. Evidently a ‘band of Saints’ travelling over the mountain to Gougane Barra stopped at this well for refreshment. One of them (St Finnbarr) left his spectacles behind and didn’t realise it until he was a long way up the steep path. Fortunately, there were so many of his companions that he was able to pass a message back down to those who were still starting off from the well and the spectacles were retrieved! But – because they were holy spectacles, they left their imprint on the rock at the well – forever. There it is in the picture above.

There are several crosses etched into the stones around this well by visitors. It’s wonderful to think of the continuity of those pilgrims seeking out the well and keeping its veneration alive – probably through countless generations.

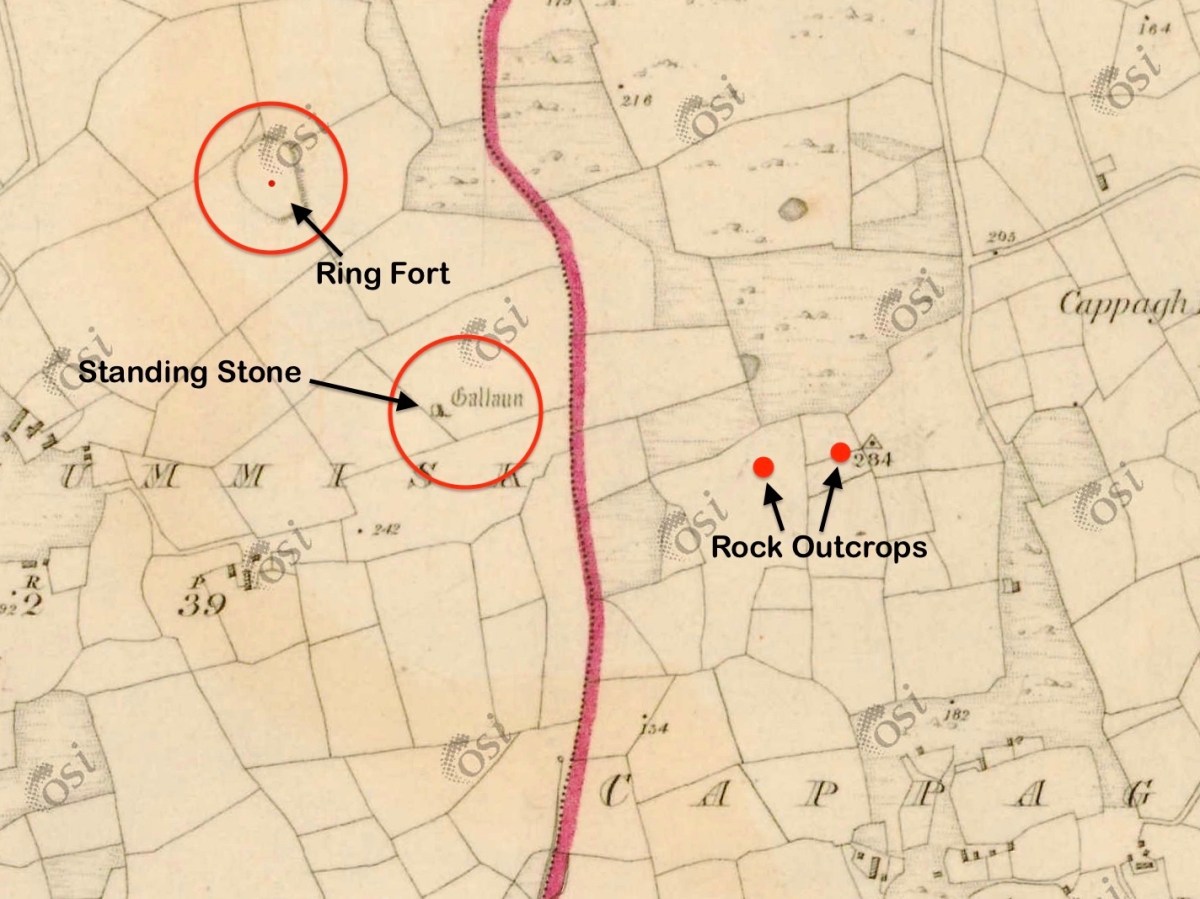

Another well on our agenda involved us walking over a long, muddy trackway. We could see the prints of the feet of other travellers: the top pic looks like bear paws (although perhaps more likely to be badgers), whereas the cloven hoof above is either Satan or a deer. We met none of these on the path that led, eventually, towards the Wells of St Peter and St Paul.

St Peter’s well is clearly defined (above, with Amanda looking on). Beyond it is a weather-worn shrine with a Calvary depiction. It’s quite a surprise to find such a substantial life-sized scene in a remote wood.

A little way to the east of St Peter is St Paul (above). He looks down on his own well. Note the modern mugs, implying that the well is still in use.

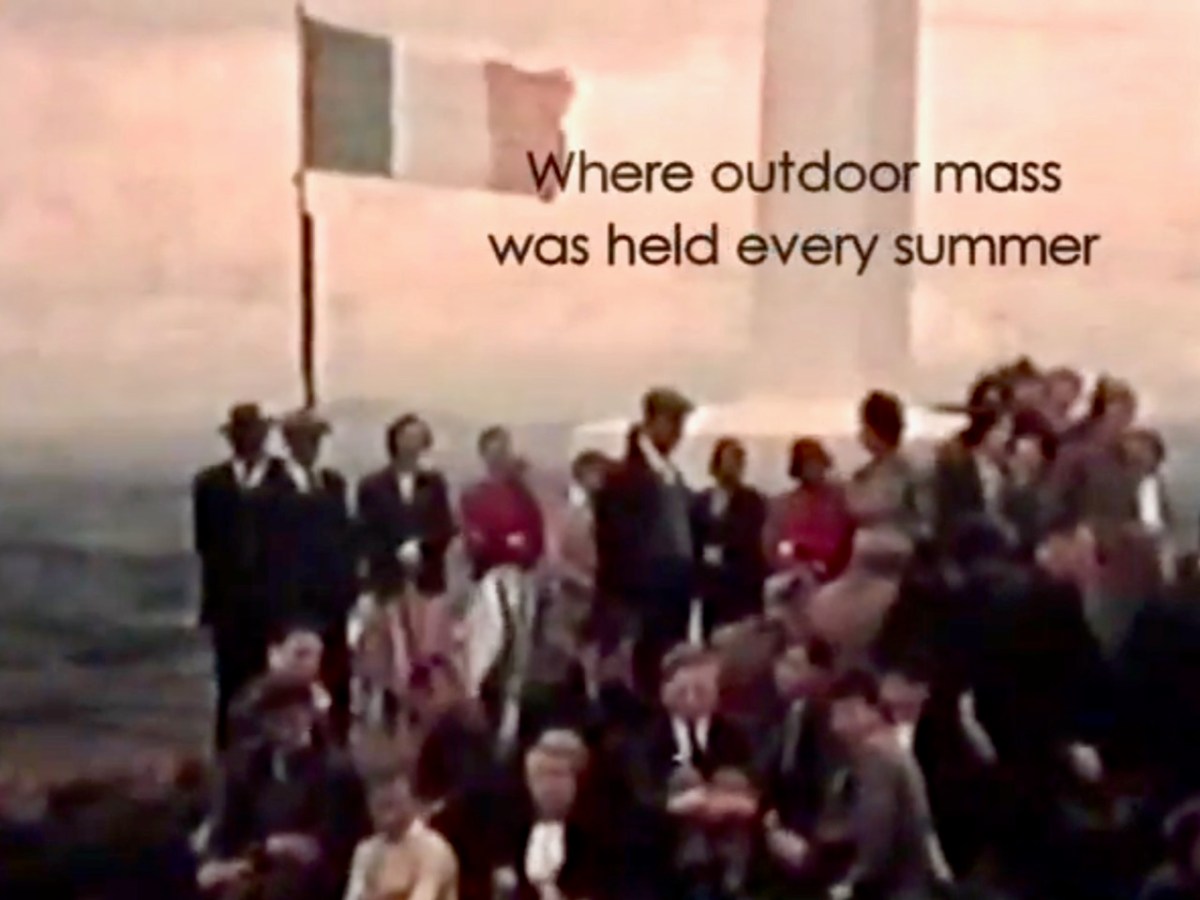

Both St Peter and St Paul share their feast day on 29th June. This is the day when these wells should be visited.

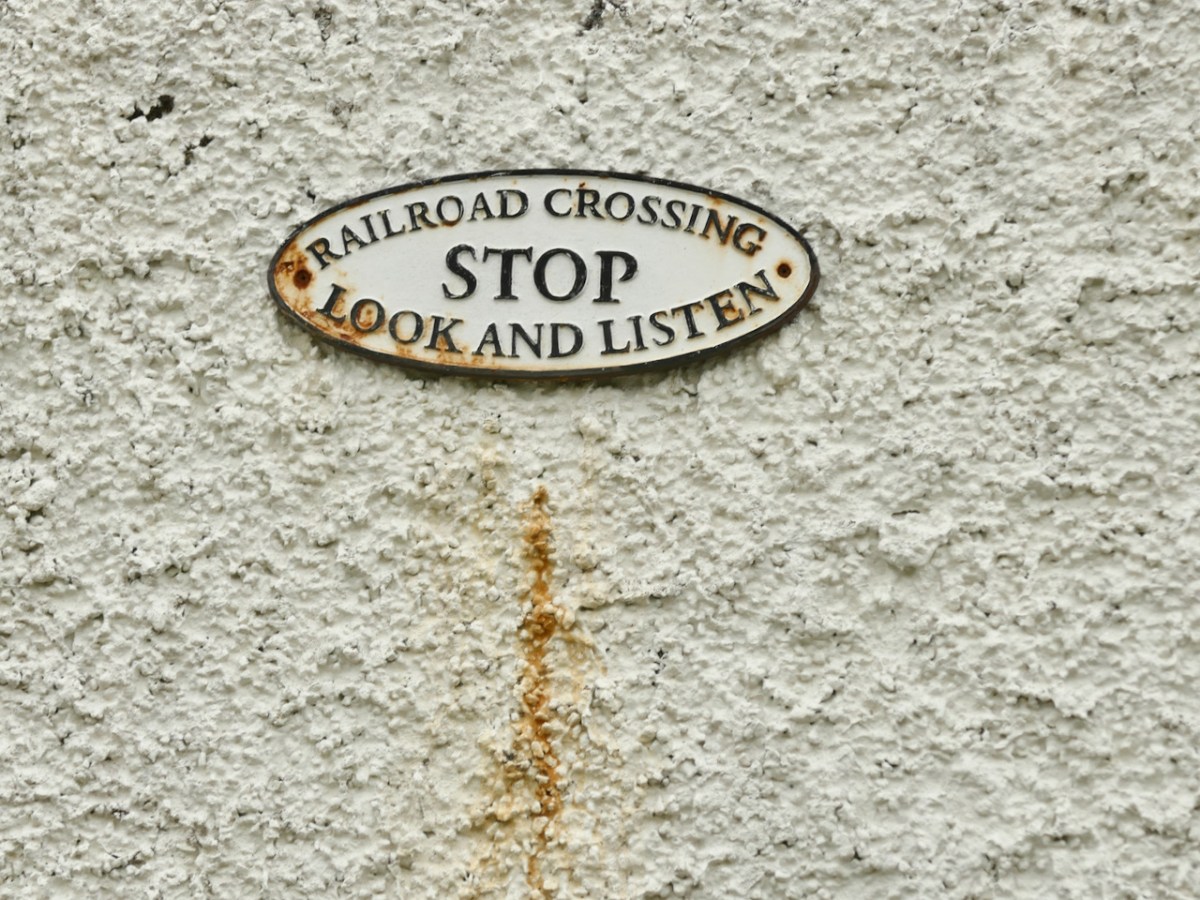

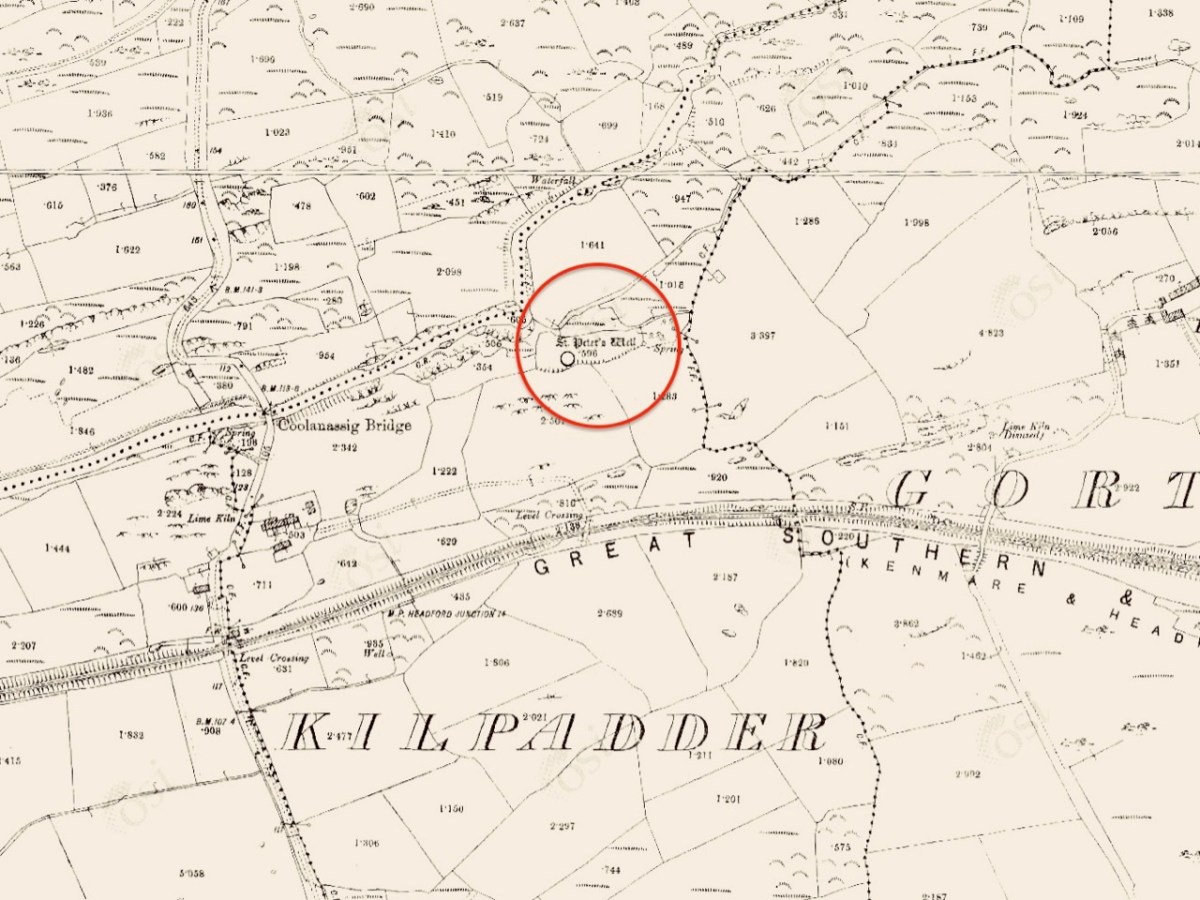

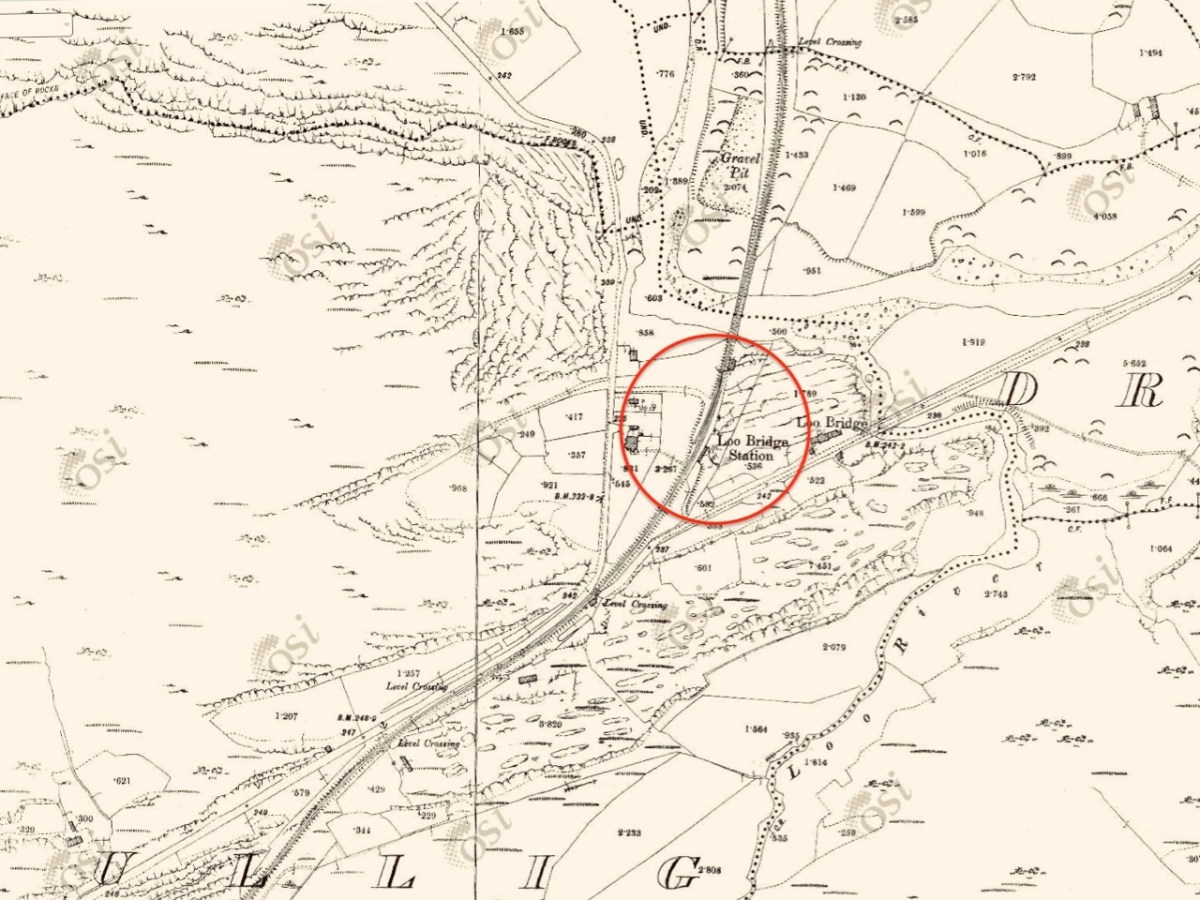

The 6″ OS map, above, dates from the late 19th century. St Peter’s well is marked on it, while St Paul’s only gets mentioned as a spring. Not far to the south is a railway line: The Great Southern Railway: Headford Junction to Kenmare. This was opened in 1890 and closed in 1959. While the track itself is long gone, many features can be traced. We stopped at Loo Bridge where the old station remains, as does an adjacent steel river crossing.

I am always saddened to see abandoned railway lines: they could so easily have had a new lease of life in our present environmentally conscious world. Regardless of their potential functionality, ‘heritage railways’ are also highly popular tourist destinations. I’m afraid, however, that the work and costs now required to recover them is unlikely to be invested any time soon, unless there is a big change in attitude and priority.

Lost railways and fading wells: unlikely bedfellows for a day out in Kerry. But our travels are always fulfilling, and diversity is the essence. In Ireland we can never run out of places to visit, or matters to be researched and recorded. Join us again, on our next expedition!