It’s been a while since I wrote about Irish Romanesque architecture, but a recent visit to Clonmacnoise included a walk to an outlying site – the Nuns’ Church – which ranks as one of the gems of this form.

If you’re new to this series of posts, you can bring yourself up to date with a quick read of previous posts, which will give you the background and vocabulary on this form of architecture – the dominant church building style of 12th century Ireland.

The Nuns’ Church was connected to the main monastery of Clonmacnoise by a causeway, still evident in places, but is now reached by wandering along a boreen that, at this time of year, is delightfully fringed with Cow Parsely, Buttercups and Hawthorn.

There is no glimpse of it in advance – you arrive at a gate, and there it is – one of the wonders of medieval architecture marooned in a peaceful little field.

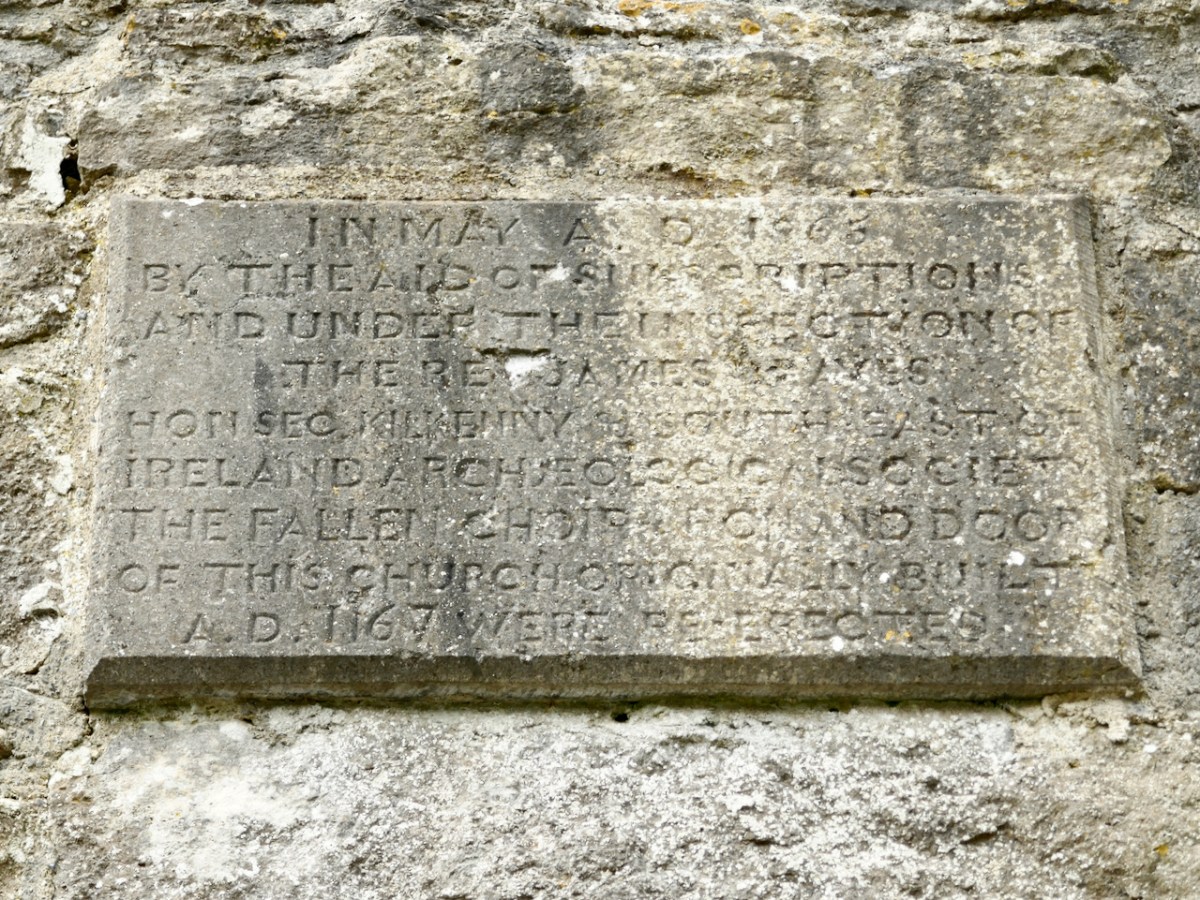

This is a nave-and-chancel church, typical of the time. It is associated with Devorgilla, wife of Tiarnan O’Rourke, as it is said to be the place to which she retired as a penitent, for the sin of absconding with Diarmuid McMurrough and being the unwitting cause of the Norman Invasion. However, there are many sides to this story, and I have just read a most entertaining version, Dervorgilla: scarlet woman or scapegoat?, which claims that she was entirely innocent of the misdeeds she is famous for. Whether she died there, or at Mellifont, as the article asserts, she was certainly responsible for re-building the church in 1167, which places it firmly in the date-range for the full flowering of the Hiberno-Romanesque style.

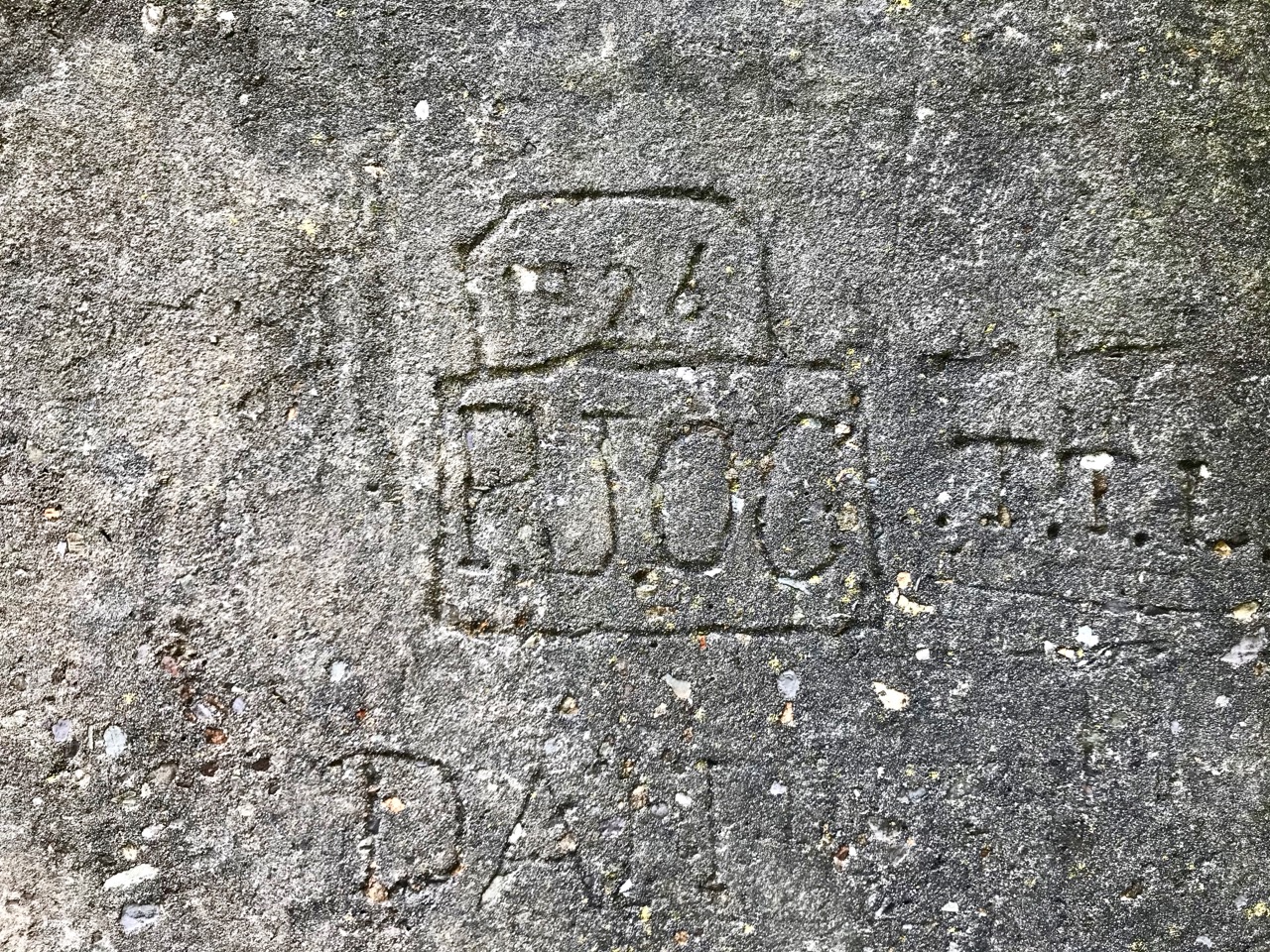

The little church was in ruins by the 1860s and one of the foremost antiquarians of the day, James Graves, of the Kilkenny Antiquarian Society, supervised the reconstruction of the chancel arch, as recorded on a plaque on the inside wall. Our old friend George Victor du Noyer was along to give advice.

By all accounts, they did a careful and informed job of it, digging out the carved stones from the rubble and debris of the collapsed arch and walls, and using a skilled mason to rebuild the arch and doorway. Du Noyer’s drawings* at the time, such as the one above, give an insight into what they found – all the pieces had to be carefully re-assembled, or replaced with ‘blanks’ to indicate what was lost.

In 1907, Thomas Westropp arrived to admire the skill of the reconstruction job and to make his own observations and drawings. (You’ve met Westropp before too, and may again.) From those drawings, it can be seen that Graves’s reconstruction has lasted intact to the present day. While not quite as accurate as du Noyer’s sketches, Westropp’s drawings are a valuable addition to the literature on this church and capture in particular the spectacular west doorway (above).**

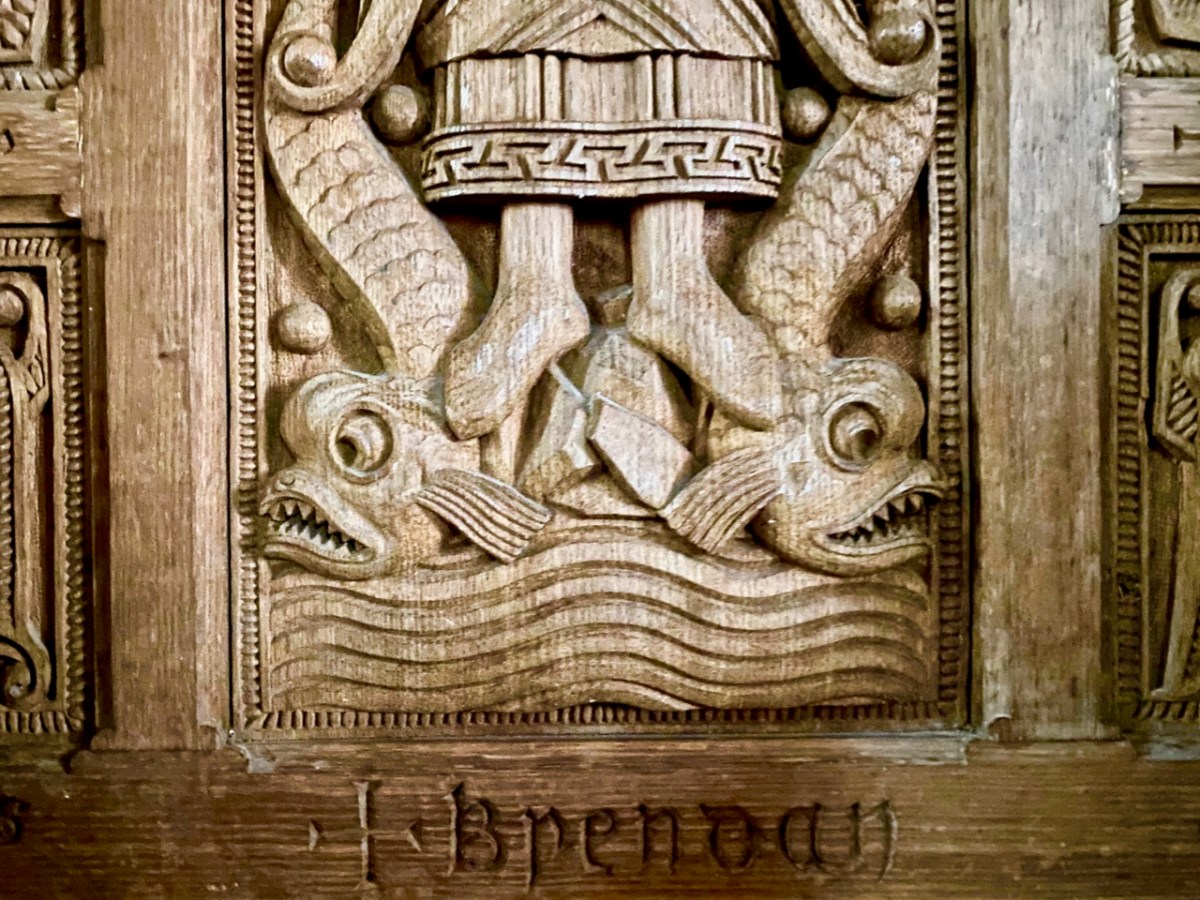

My Romanesque Bible says of the carvings on the Nuns’ Church, The emphasis on low-relief ornament and the use of zoomorphic elements are typical of Irish Romanesque and show the adaptation of English and Continental Romanesque influences to the traditions of Insular art. That’s a fancy way of saying that there are lots of animal motifs here. Most obvious are the voussoirs of beast heads biting on roll moulding that form the arch of the second order of the four orders of the West doorway.

But monster heads and snakes are seen here and there on capitals and jambs, as well as all the usual chevrons, roll mouldings, foliage and interlace patterns.

The chancel arch is equally highly carved. Among the intriguing elements are the capitals on the both sides of the arch, which have both human and beast heads, together with geometric ornamentation (such as a Greek key design), rows of cats’ heads, and beading.

Westropp’s drawing and my photographs above, of the north side of the chancel arch and below, of the south side.

Westropp’s drawing also shows the base or plinth of the jambs, which he says are quite unusual because of both the ‘strange bulbs’ and the ‘discs displaying crosses.’ My photo of what he’s referring to is below.

In one of the lozenges formed by the two rows of chevrons, carved point-to-point on the chancel arch, is an exhibitionist figure – a tiny head and legs, with the legs pulled behind the head. Can you see it in the photograph below?

How about this one, below? It’s been interpreted as a sheela-na-gig, a similar exhibitionist genitals-displaying figure, although this one is a lot smaller than a typical sheela.

Give yourself enough time here to trace the carvings with your eyes – there is so much detail to observe and some of it is easy to miss.

The small field is full of bumps and hollows – evidence that this was once the centre of a convent with substantial buildings around the church, separated, of course, by a ‘decent’ distance from the male monastery, but connected by those causeways.

Many people who visit Clonmacnoise don’t realise that the Nuns’ Church is only a short stroll away and never see this tiny, perfect example of Irish Romanesque architecture. Now – you’ve been let in on the secret!