It’s about as far away as we can get from St Patrick’s Day, so it’s probably ok to talk about snakes in Ireland…

Ah yes – the old fable that he banished all the snakes out of the land…

That’s enough of the ‘old fable’ – there’s no doubt about it: there are no snakes in Ireland at all, so it must be true that St Patrick sent them packing! Although I was a bit alarmed when, out walking in the Mayo hills a while ago, I came across this…

A slow-worm? Anguis Fragilis… How does that fit into the St Patrick story?

Well, there shouldn’t be any slow-worms here really – as the Saint expelled all the reptiles and lizards – and that’s a lizard. But evidently someone introduced them into County Clare illegally back in the twentieth century, and they’ve survived there. (Frogs were also introduced, incidentally, as a food source by the Normans). My sighting in Mayo, however, is something of an anomoly…

But didn’t I hear that these serpenty creatures couldn’t actually live on Irish soil because of Ireland’s purity?

Now you’re talking. It’s perfectly true that if you try to bring a snake into Ireland it drops dead as soon as you enter Irish waters…

Now you’re talking. It’s perfectly true that if you try to bring a snake into Ireland it drops dead as soon as you enter Irish waters…

Oh? Has that been proven?

Indeed – by Gerald of Wales. He lived in the twelfth century and states that ‘…it is a well-known fact that no poisonous thing can live in Ireland and if Irish soil is taken and scattered elsewhere it will expel poisonous things from that vicinity…’ Other stories mention toads brought to Ireland by accident (having, presumably, stowed away in the holds of ships) ‘…which when thrown still living onto the land, turn their bellies up, burst in the middle and die…’ Perhaps you’ve heard of the Fir Bolg?

I think so – aren’t they one of the early races who inhabited Ireland?

They are – and the name means Men of the Bags. They carried bags of Irish soil around with them when they travelled all over the world, because they would be kept safe by its serpent slaying properties…

I like that idea – remind me to go and do some digging in the garden. Where are you getting all this information from?

Much of it out of a most wonderful book: Ireland’s Animals by Niall Mac Coitor (The Collins Press, Cork 2010), but there are plenty of other early sources, many of which Mac Coitor admirably collects together. Perhaps the best of these is the old medieval Irish text Lebor Gabála Érenn – the Book of Invasions. I have already quoted from that in my story of Cessair, the very first person to set foot on Ireland in 2680 BC…

Yes, I remember that. She was Noah’s grand-daughter. Wasn’t it the case that Ireland was supposed to have been a land without sin, which is why she went there to escape the flood?

That’s her. And it’s a nice bit of symbolism that Ireland was without sin because it had no serpents…

But hang on – that was Old Testament times – long before the saints…

You do have a point there. And, you know, in archaeological terms there are no fossil records of any reptiles having ever been here in Ireland – except for one: the common lizard Lacerta (Zootoca) Vivipara which has always been here, and still is…

Now I’m getting very confused about St Patrick…

Don’t worry about it – it’s a grand story…

Yes, I have this picture of our good saint standing on the top of Croagh Patrick in Mayo and all the crowd of little snakes and reptiles climbing up there to surround him, only to be cast down to their doom by a sweep of his crozier…

Hmmm… but surely they would have just rolled and bounced down to a soft landing at the bottom? It’s only a hill, after all…

You’ve obviously got something else in mind?

Well I like the story of St Patrick’s Chair, which is at Altadaven, Co Tyrone. The Chair is a huge boulder which seems to have been carved into the shape of a chair or throne. Beside it is a holy well – also ascribed to St Patrick – which appears to be a bullaun stone: offerings are made at the well and the trees around it are hung with rags and tokens. Altadaven means Cliff of the Demons, and it was evidently where all the snakes, serpents and reptiles once lived. The saint went there, sat on his chair (presumably) and cast them all down the cliff and into Lough Beag below…

Which is a bit different to just rolling down the hill at Croagh Patrick…

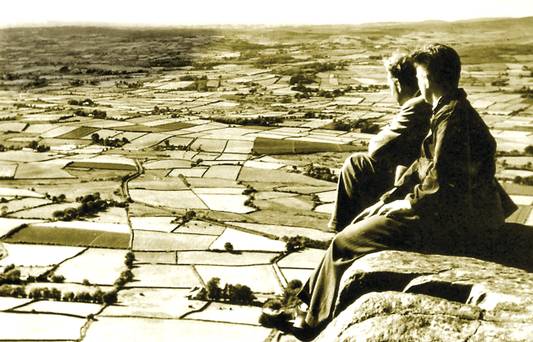

Another St Patrick’s Chair at Slieve Mish, Co Antrim – this one looks like a good candidate for the place where the snakes were cast down… (Irish Times 1956)

And there was a tradition at Altadaven of an annual gathering known as Blaeberry Sunday or ‘The Big Sunday of the Heather’, probably connected with Lúnasa customs. People would climb the rock to sit in the chair and make a wish which, of course, always came true. Then they visited the well and left pins and pennies behind…

Anything else we should know about reptiles in Ireland?

Well, earlier this year one of the world’s rarest turtles – the Kemps Ridley Sea Turtle – appeared in Donegal. Unfortunately it was dead – washed up on the beach. But there are also other small turtles which do inhabit Irish waters.

The exception to the rule, possibly. But perhaps being in the water isn’t quite the same as being on the land…

I’m always keeping my eyes open. I had a ‘serpent’ experience once, in Devon. On my first visit to St John’s holy well up on Hatherleigh Moor I opened the door to the well (which was surrounded by a stone built enclosure) and there inside was an eel swimming around!

I heard that’s a very good omen – to see an eel in a holy well?

Oh yes – why wouldn’t I be a total believer in such things? In Celtic Brittany holy wells are always protected by a ‘Fairy’ who has the form of an eel, and is a benign spirit. Interestingly, though, there is no stream or watercourse near to the Hatherleigh well, so the eel must have travelled some away across the moor to get there – on dry land!

So – I have to ask: are there eels in Ireland?

There are – Anguilla Anguilla – It’s a fish, so not a problem to the saint. Eels have been eaten in Ireland since the earliest human times and have been found in association with Mesolithic sites such as Mount Sandel, Co Derry.

Thank you – you’ve taken us on a serpentine tour through Irish history and mythology…