Every so often I have to come up with a post about hares – they are an obsession with me, and have been for as long as I can remember. So, when I looked out of the window this morning and saw a real, live Irish Hare foraging in our garden at Nead an Iolair I knew the time had arrived to pen another paean to this most beautiful and elusive of animals. Lepus timidus hibernicus is Ireland’s only native lagomorph; the other two are the Brown Hare and the Rabbit – both have come from elsewhere. But the Irish Hare has been here at least since the Pleistocene: that’s getting on for three million years ago, implying that the species is totally attuned to its habitat.

Here is the hare that arrived on our doorstep today. We know that this is an Irish Hare because of his ears – shorter than the length of his head: the Brown Hare species has ears which are longer than the head.

Before I came to live permanently in Ireland I frequently visited West Cork, and a hare sighting in the wild could be virtually guaranteed each time. Also, when we first came here in 2011, we would encounter a hare or hares once every few weeks. In the last couple of years, however, hares seemed to have disappeared completely, apart from a notable day in August 2018: it was the most soaking of wet Irish August days, and we found that we had the most bedraggled of Irish hares sitting forlornly on our terrace.

As you can see, it was a mere youth – no more than a slightly matured leveret. We invited him indoors for a dry off, but he wasn’t having any of that; however, he did hang around for three days, allowing us to get a few more pictures.

We named this little hare Berehert, after an Irish saint we were researching at the time, and wrote a post about him here. In fact, hares seldom stay in one place for very long – it’s part of their self-protection mechanism to be always on the move. And they do move: they are our fastest mammal and can outrun everything else. Since Berehert departed I always harboured a little fantasy (should we say conviction?) that he would one day call in again to let us know how he was getting on… Very nicely, thank you, would seem to be the order of the day if it is, indeed, Berehert who has come along to test out our lawn – this animal appears to be in fine condition.

But maybe there’s another reason why this handsome hare has decided to honour us with his presence: could it be the new sculpture which has appeared in the garden? It is temporarily lodged down by the hedge (header picture) but it has been expertly laser cut from stainless steel (by Pre-Met Fabrications of Cork City) to grace our recently built stone gatepost at our entrance. My design for this hare incorporates the moon, because in folklore all around the world the hare is associated with the moon; it’s artistic licence that I have exaggerated the length of the ears (thereby making this a Brown Hare rather than an Irish one!) but the ears of hares are such defining features that they ought always to be fully celebrated.

Finola is giving you the scale of the new gatepost hare, above, and trying him out at his final location. The sculpture was a special birthday treat from Finola – an indulgence for which I am most grateful: she long ago banned me from bringing any more hare inspired accoutrements into the house, which currently harbours scores of them. I’m afraid that’s par for the course if you marry a hare fanatic!

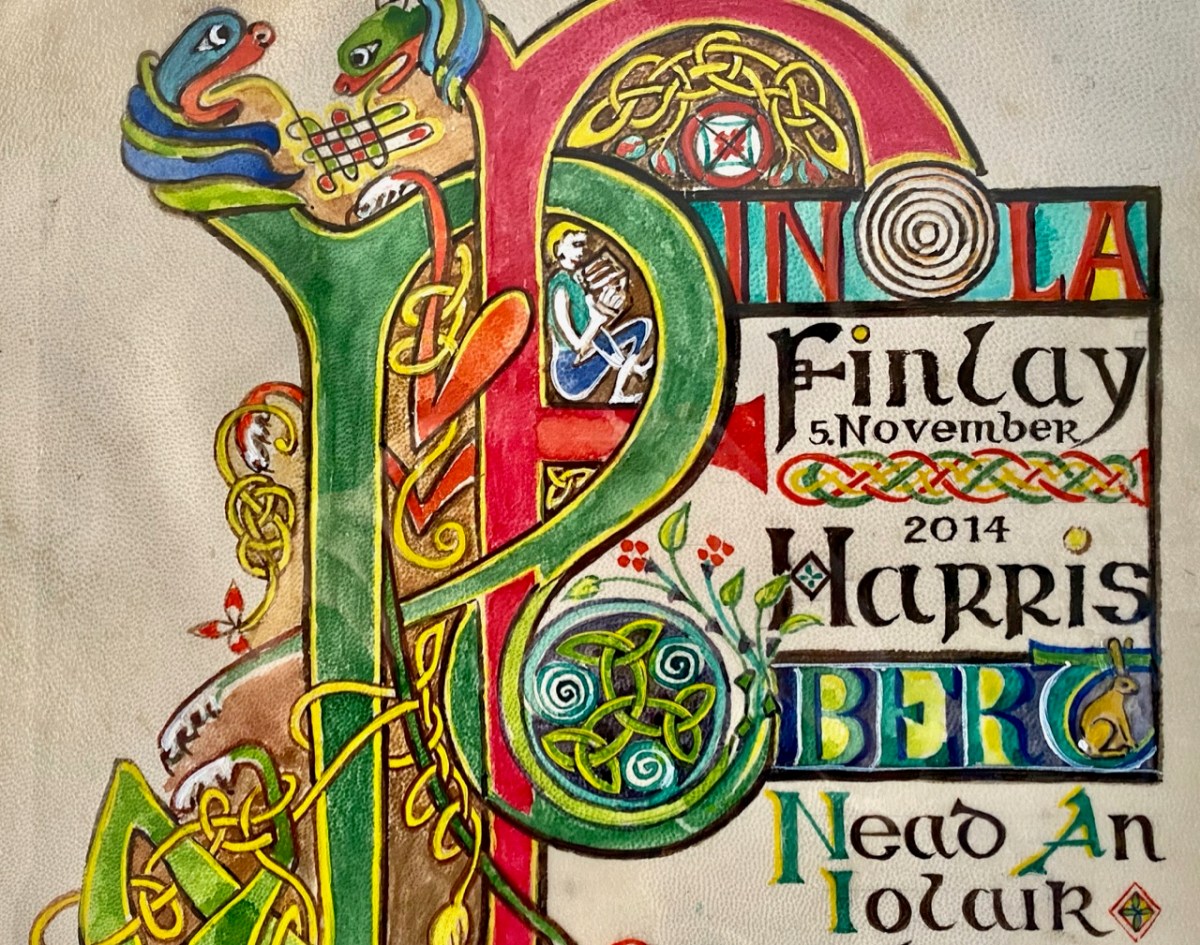

The very fine parchment scroll (above) which was made and presented to us by our neighbours Hildegard and Dietrich to celebrate our wedding has a little hare at the end of ‘Robert’!

You may remember that Finola’s stained glass window that was crafted for us by George Walsh incorporates a wonderful golden hare (at my request), flanked by my own concertina – playing the magical music of the Children of Lir – and a piece of rock art recorded by Finola in her days of yore.

Have a look at this ‘post from the past’ if – like me – you just revel in the elegance of the hare . . .