We often find time to visit the east side of the country – where we see everything from a different perspective! But we are just as interested in history and archaeology over there as we are here in our own West Cork. Today I am bringing together three sites from three different eras – all equally fascinating, and all within a stone’s throw of each other, hovering on the borders of South County Dublin and County Wicklow.

From the high ground in these two counties you find stunning views to the north out across Dublin Bay, with Howth in the distance. The twin striped chimneys on the right of this picture are protected historic structures: they date from 1971 and were built to serve the Poolbeg electricity generating station. At 270m they are amongst the tallest artificial structures in Ireland and are a visible feature on the skyline from many parts of the city. The power station closed in 2010.

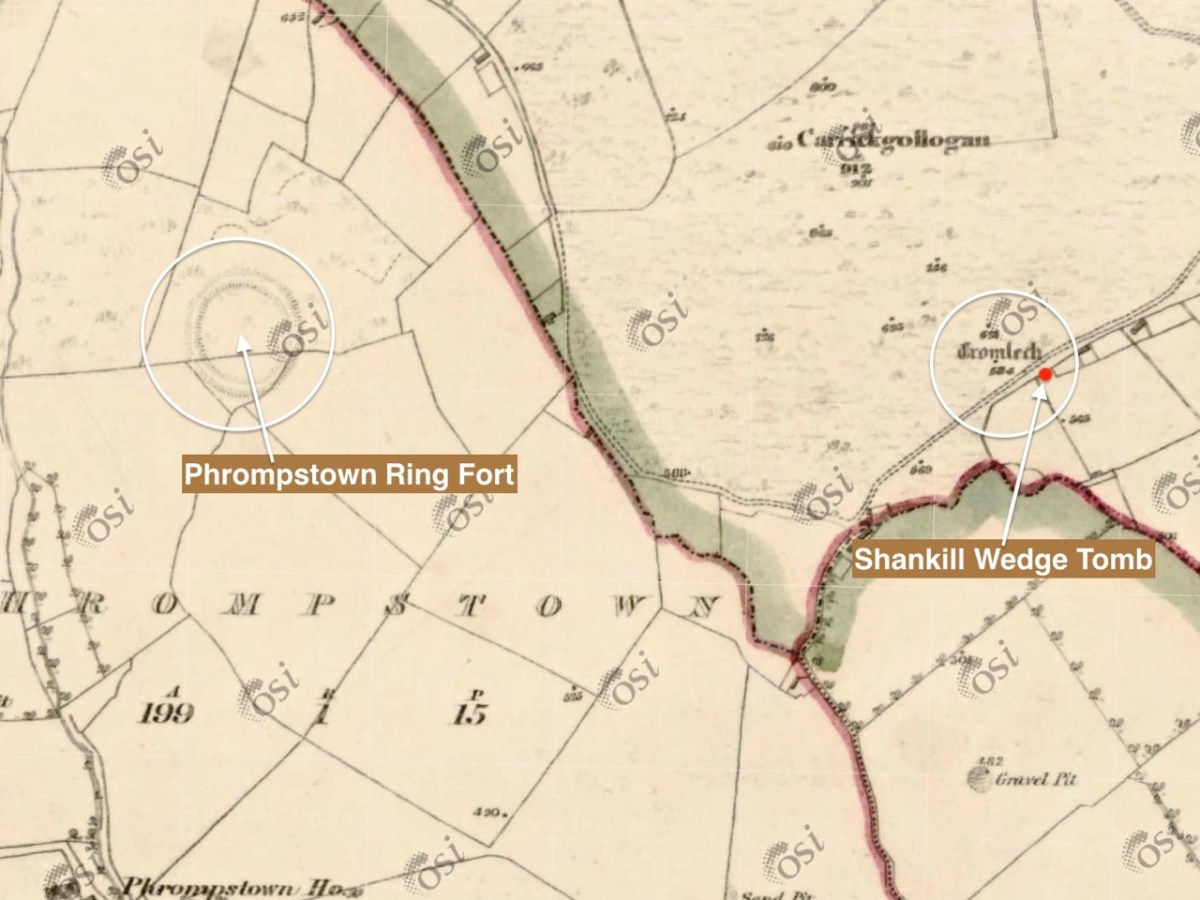

The first site we are visiting in this little tour is the wedge tomb in Shankill townland, County Dublin. It lies below Carrickgollogan hill, and commands distant views to the two distinctive Sugar Loaf peaks, which are situated in County wicklow. Or – let’s say – it should command those views, but it now reposes in a rather neglected state, engulfed by a modern hedge boundary, which you can see below.

The picture above is taken a little to the west, to show the full skyline profile. The monument is not in good shape: the photo below (courtesy Ryaner via The Modern Antiquarian) shows the tomb in 2006, when the capstone remained intact on its supports. In less than two decades the capstone has fallen, as you can see from our photos taken a few days ago.

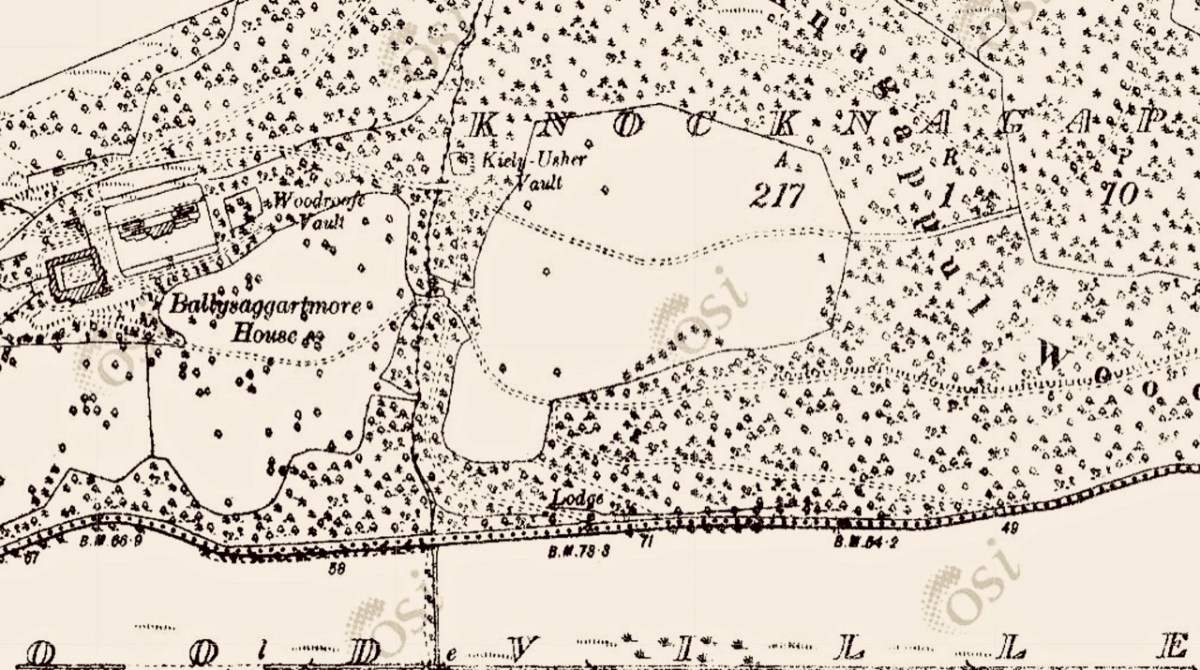

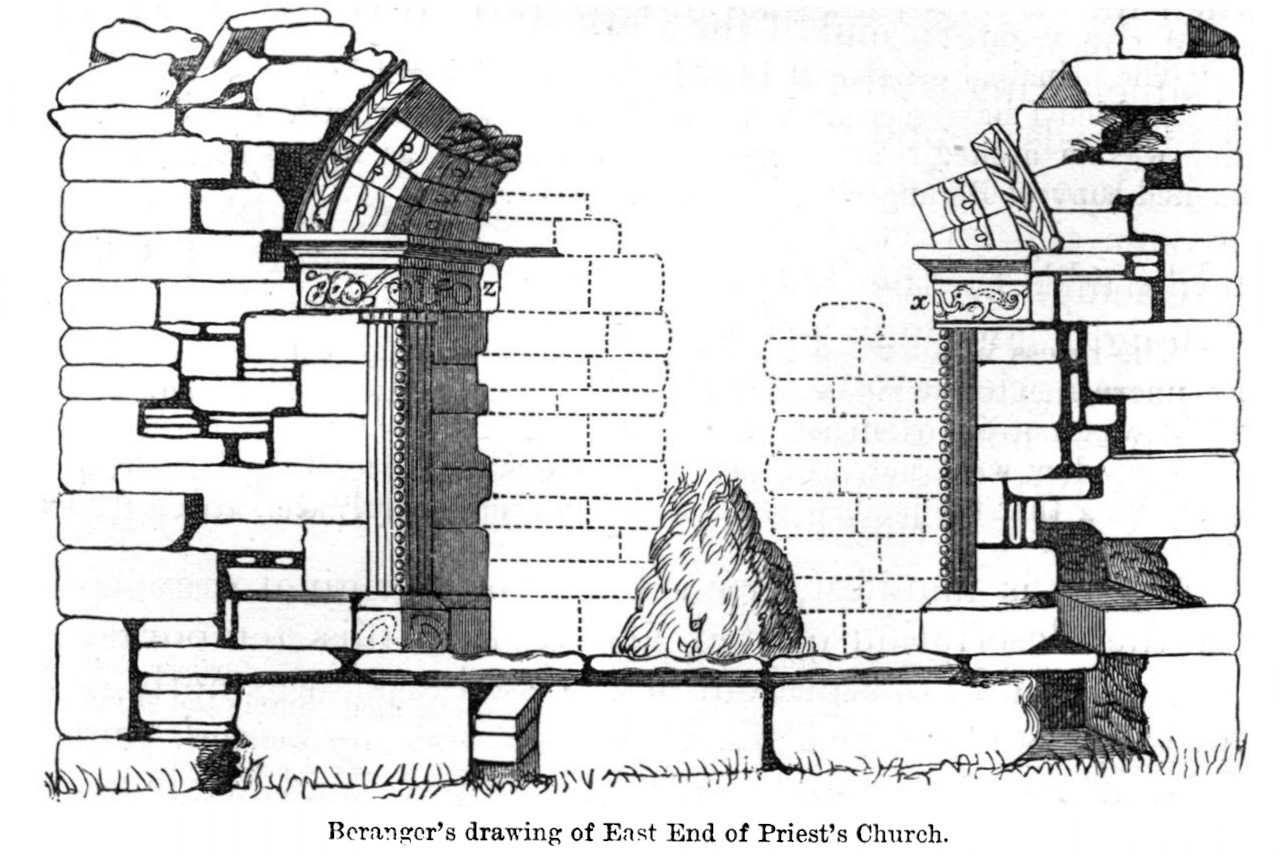

It is quite difficult to penetrate the undergrowth to see what remains of this structure, which probably dates from between 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. It seems a shame that such an ancient survival is not cared for in any significant way by our State. The tomb was recorded (as a ‘dolmen’) by the archaeologist William Borlas in 1897. Just over a century later, it has significantly deteriorated. The extract (below( from the first edition 6″ OS map gives it the title ‘Cromlech’ – and also shows nearby a substantial ring-fort: there is no trace of that remaining today.

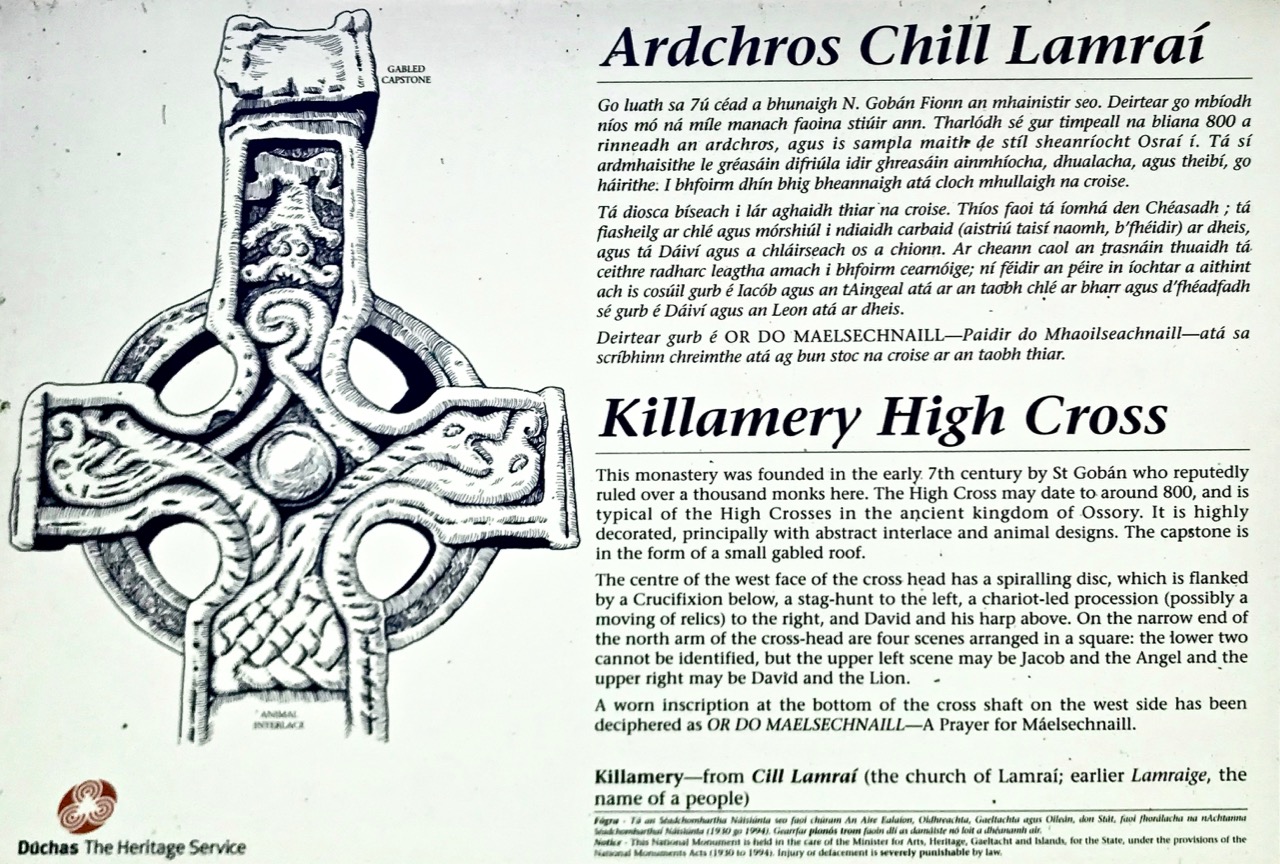

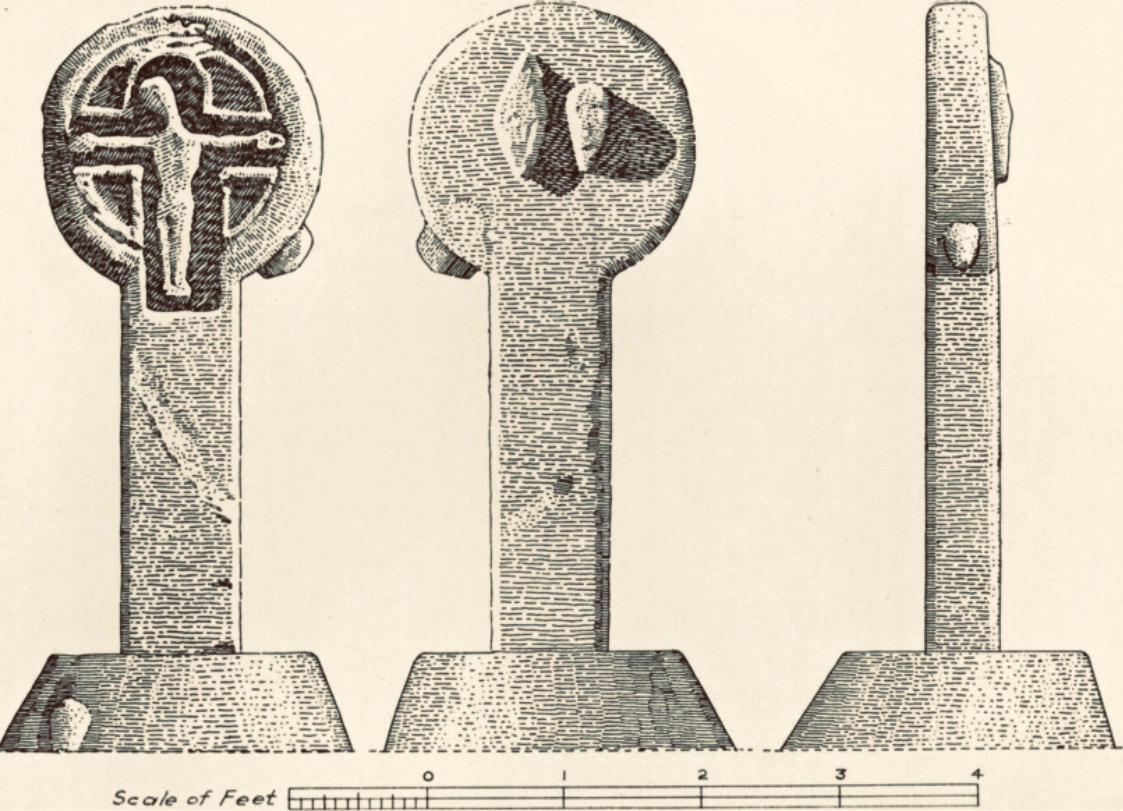

We leap forward about three thousand years for our next archaeological site, but we are only a short distance away as the crow flies – in Fassaroe, Co Wicklow, less than half a kilometre. This was a great discovery for me: a very fine carved cross, likely to date from the 12th century. Although it has been moved from its original site, it is cared for, and easily found right beside a strangely deserted modern traffic roundabout with little sign of habitation nearby.

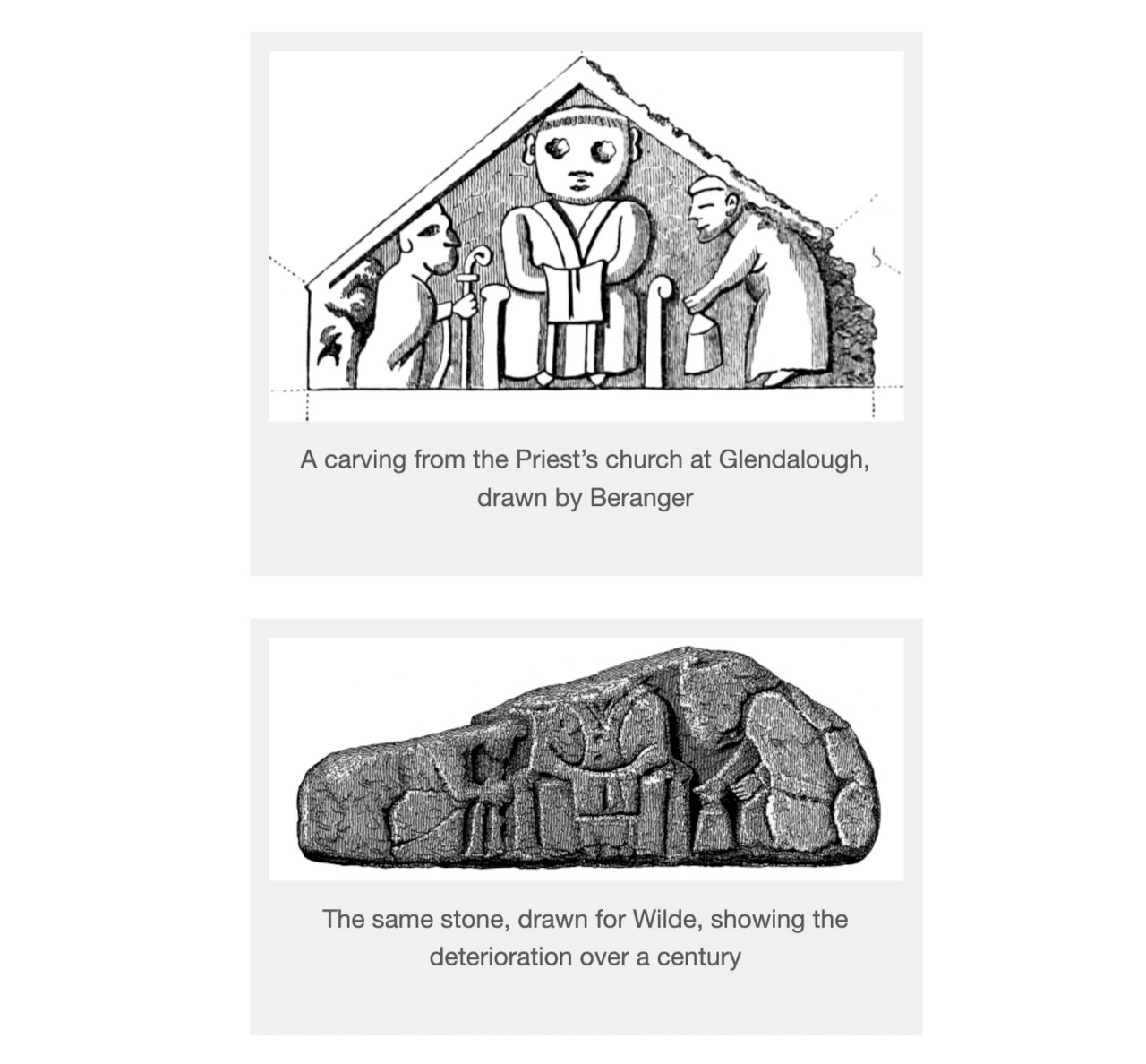

The granite cross face is carved with a crucifixion, but there are also ‘bosses’ on the back, sides and base stone. These are believed to be heads, well worn now but in good light some features can be seen: a pointed ‘ceremonial’ head-dress, and beards.

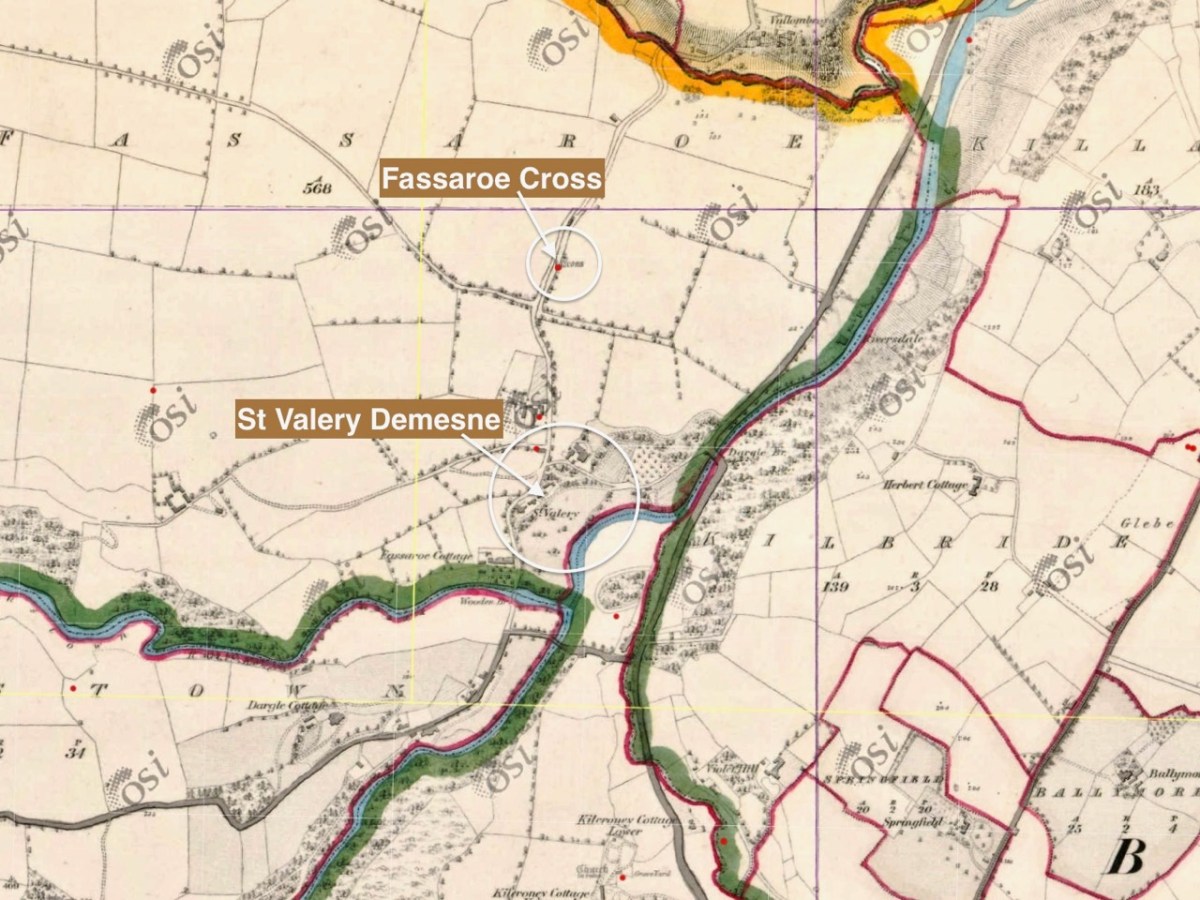

The clearest view of the carvings (above) is illustrated in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 88, 1958. An article by P Ó hÉailidhe discusses this cross and others nearby. The carving is popularly known as St Valery’s Cross as it purportedly came from the nearby demesne of that name. Some archaeologists theorize that it was originally brought to that estate from elsewhere.

This extract from the first edition of the 6″ Ordnance Survey map (c1840) shows the location of the cross, not far from St Valery.

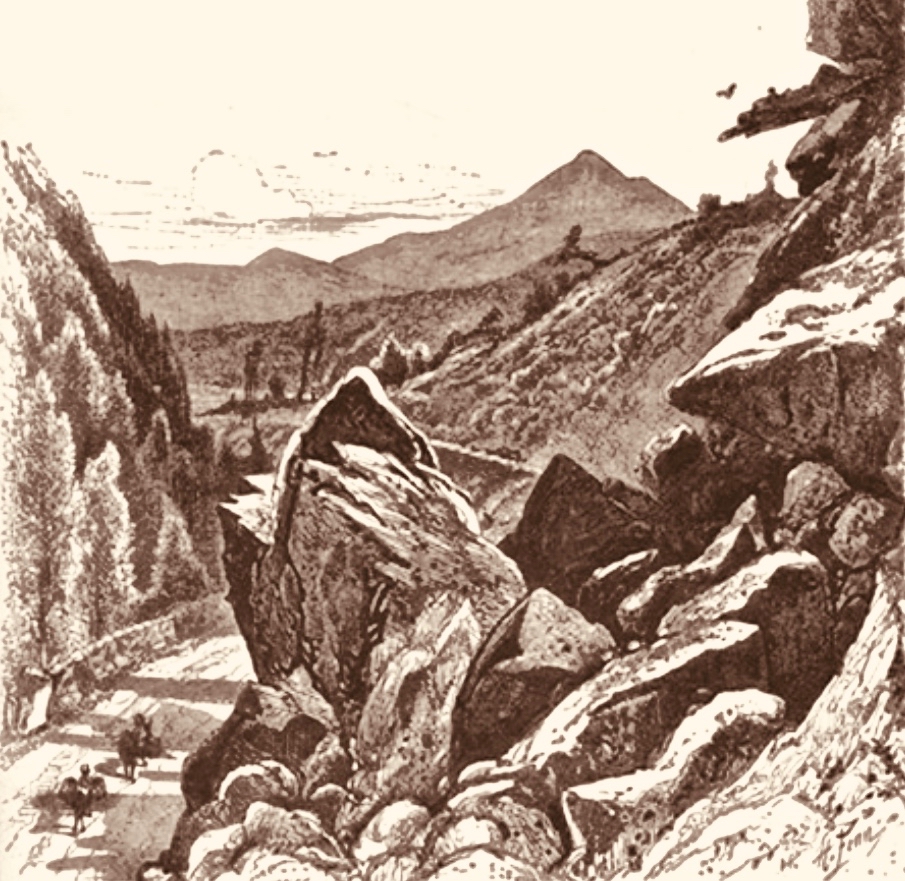

It’s about 7km from the Fassaroe Cross to the last stop on our journey. We have to head north on a road that takes us through The Scalp.

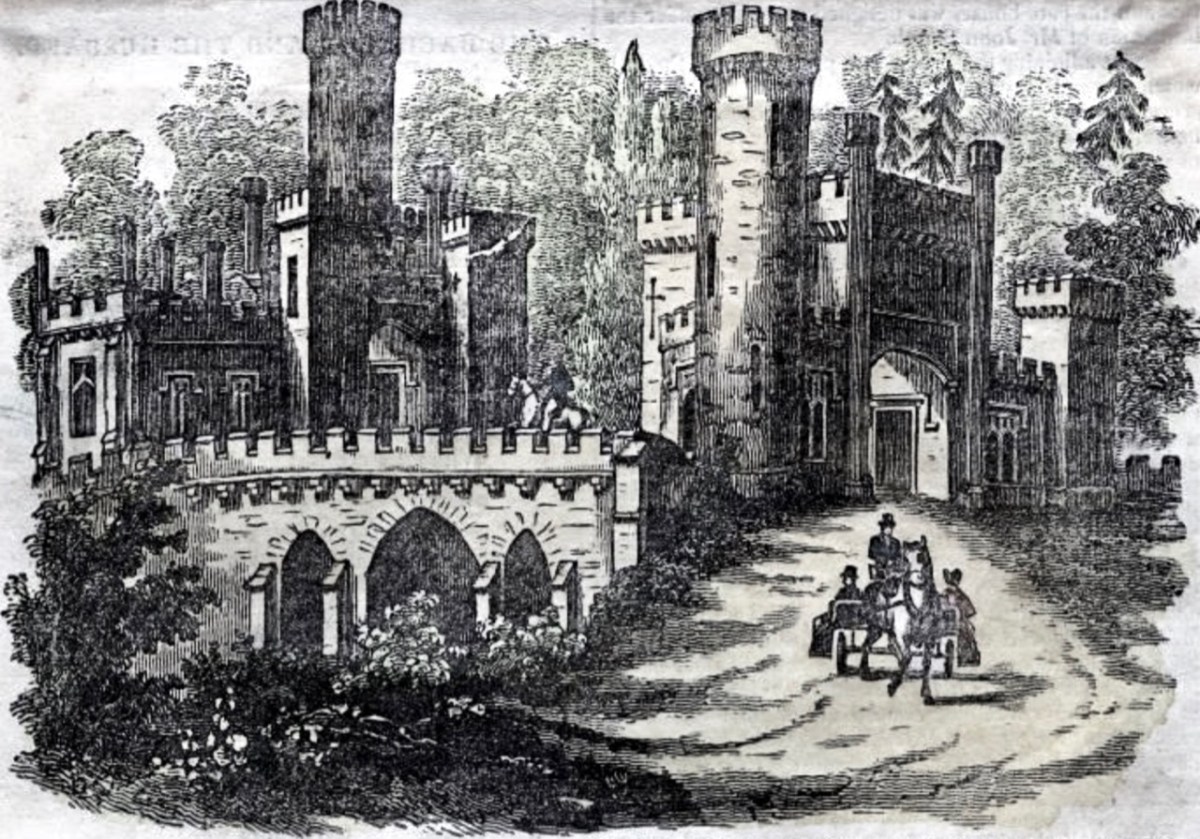

. . . Within an easy drive of Bray is a wild ravine known as the Scalp. The road runs over a shoulder of Shankhill Mountain and through this ravine; it presents a very wild appearance, enormous masses of granite being heaped up in grand and picturesque confusion on either side. It looks as if nature, in order to spare man the trouble of blasting a road, had by some mighty convulsion torn a rent through the mountain just wide enough for a high road . . .

Irish Pictures Drawn with Pen and Pencil, Richard Lovett, 1888

The view above accompanies Richard Lovett’s 1888 account. In spite of the topological interest of the Scalp road, our journey took us on and forward a few hundred years to our last stop – the lead workings on Carrickgollogan hill, Ballycorus townland. The hilltop mine chimney which forms our header picture is a well-known landmark in this part of the country.

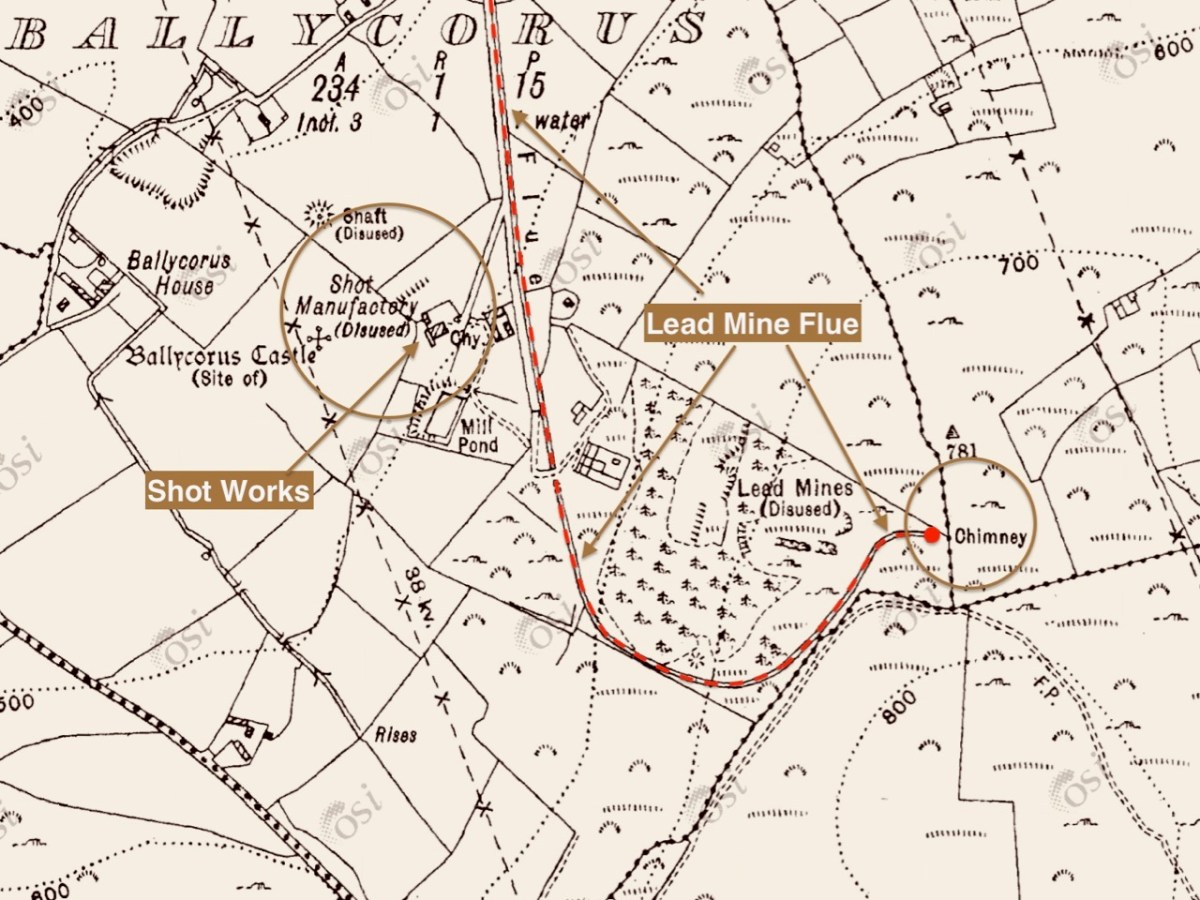

The mine was established in the early nineteenth century. Many of the lead works buildings remain today in the valley below the landmark chimney, mainly converted to modern dwellings: the photo above (courtesy Joe King via Wiki Commons) shows a distant view of the converted buildings and ‘shot tower’. The ‘Shot Works’ can be seen on the 25″ OS extract, above. This also show the location of the Lead Mine flue and chimney, which was the destination of our archaeological journey. That’s us (below) climbing the hill towards the chimney that’s on the 220m contour line, and offers views towards Dublin Bay.

Open-cast mining commenced in 1807. The Mining Company of Ireland took over the site in 1826 and began to carry out underground extraction. A 2 km long flue (shown in red on the map above) was laid out from the smelting facilities to the great chimney at the summit of the hill. You might think this was an acknowledgment of the poisonous fumes which lead working released, and an attempt to divert those fumes from the main site – but no!

. . . A process had been discovered in the 1770s whereby additional quantities of lead could be extracted from the fumes emitted by reverberatory furnaces if the vapours could be trapped long enough to precipitate the lead. To this end a flue 2 kilometres long running from the lead works and terminating at a chimney near the summit of Carrickgollogan was constructed in 1836. The precipitated lead deposits were scraped out of the flue by hand and many of the workers subsequently died of lead poisoning, giving the surrounding area the nickname “Death Valley”. . .

Wikipedia

The lead mine chimney remains – although a brick upper section was removed in the twentieth century for safety reasons (see lower picture) – and so does much of the enclosed flue. A public trail follows its course to the top of the hill. The remaining chimney is a fine granite structure, in reasonably good condition. It’s certainly much visited: Finola – who grew up in Bray – has fond memories of cycling out there with her two brothers, and finding ways to climb part way up the spiral staircase which accessed a viewing platform, in spite of key parts of the stair structure being missing!

All three examples of archaeology we have studied today have one thing in common: they are constructed of local granite. Thousands of years separate the oldest and the most recent, but the inherent strength of the material has ensured survival, at least in part. As with West Cork and all other parts of Ireland, the temporal history is rich, and much of it is largely intact. We have so much more to explore!