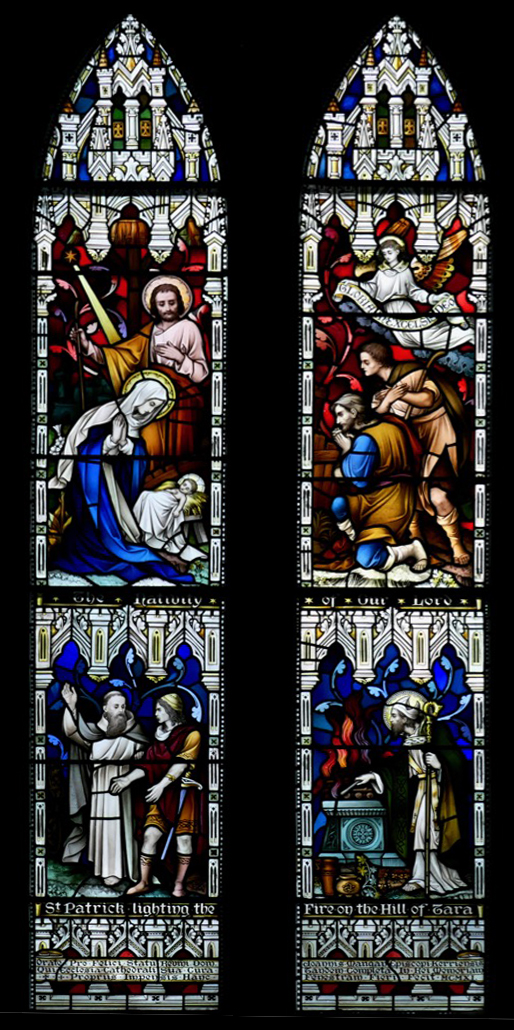

Every Catholic Church in Ireland has a set of Stations of the Cross on the wall – fourteen focus points for devotion and reflection on the Way of the Cross. The Stations, as they are universally known in Ireland, come from a long tradition within the Catholic Church, often associated with St Francis, but also with the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, and the custom that Pilgrims had of retracing Jesus’ footsteps on the way to Calvary.

Most Stations appear to have been ordered from a catalogue and all look similar, painted in an Italianate Renaissance style and framed in wood. The image above, of one of the stations in a rural church in Cork, is typical.

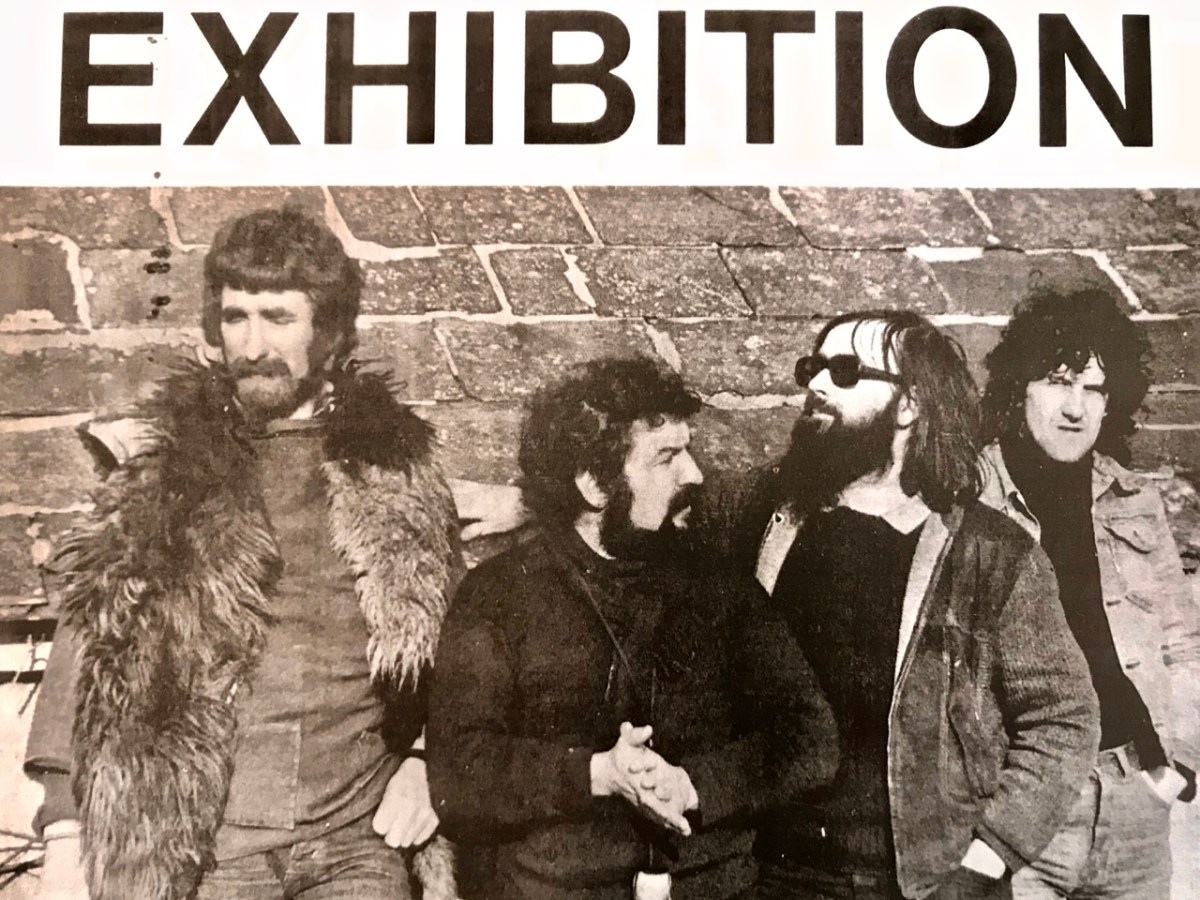

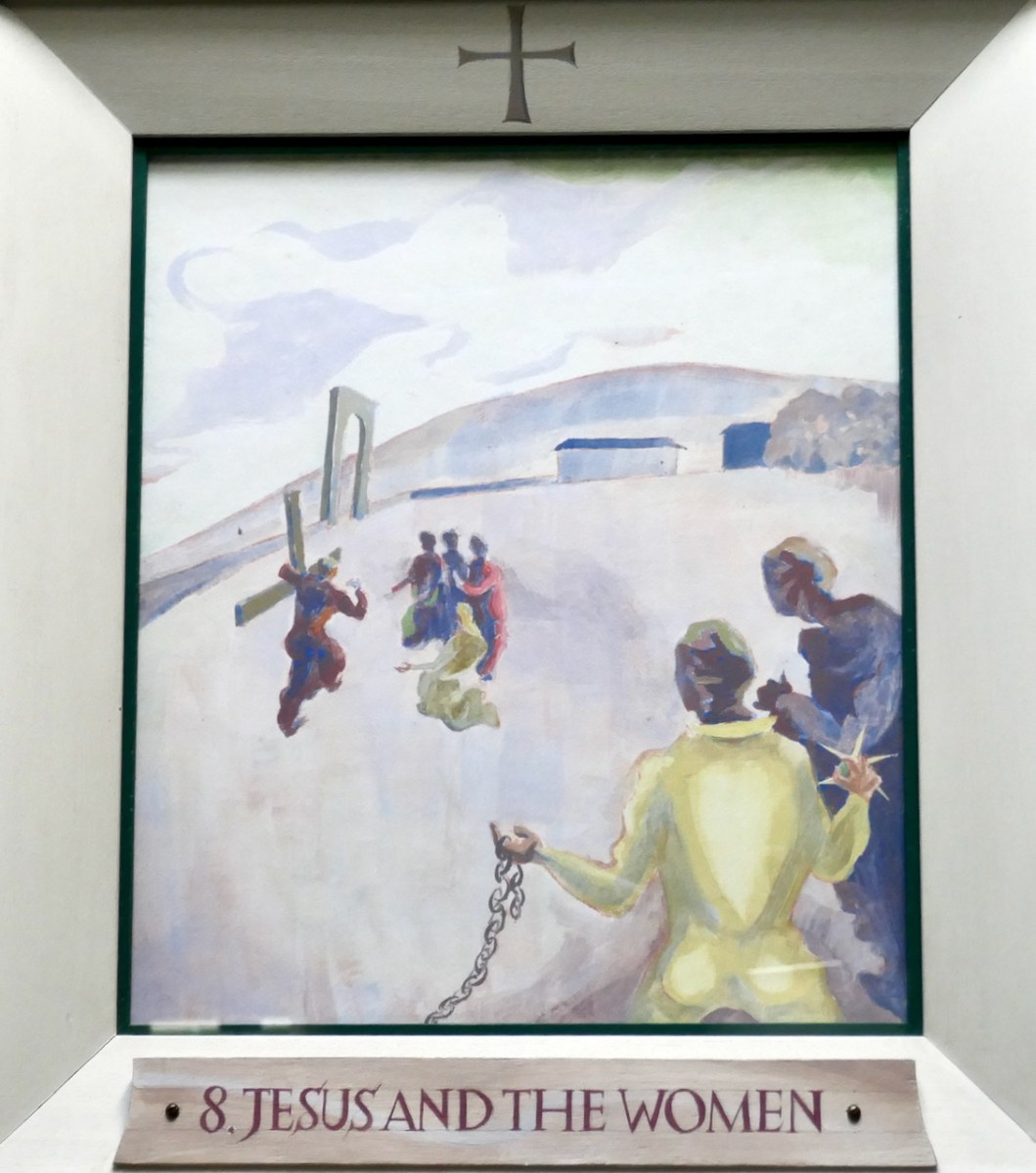

However, architects, priests, and parish committees sometimes took the bolder step of commissioning Stations from a contemporary artist. The lead image and the one above are both from sets of Stations by Richard King. The lead image is the Deposition (Christ taken down from the Cross) and is in a small church in Foilmore in Kerry, while that immediately above is from Swinford, Co Mayo, as is the one below – a painting that focuses ferociously on the suffering of the crucified Jesus.

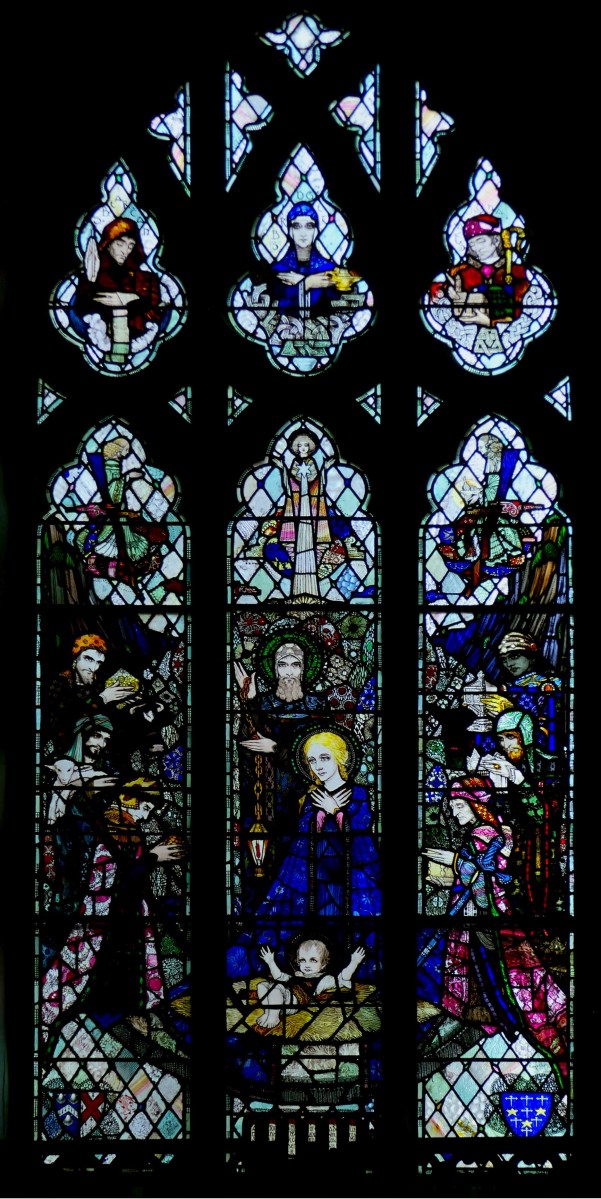

This was an important source of income for artists from the beginning of the new Irish State. While we don’t often think of the Catholic Church as a patron of the arts, in practical terms it functioned as such for many painters and sculptors. In fact it is hardly an exaggeration to say that the church was the largest commissioner of contemporary art in Ireland during most of the twentieth century.

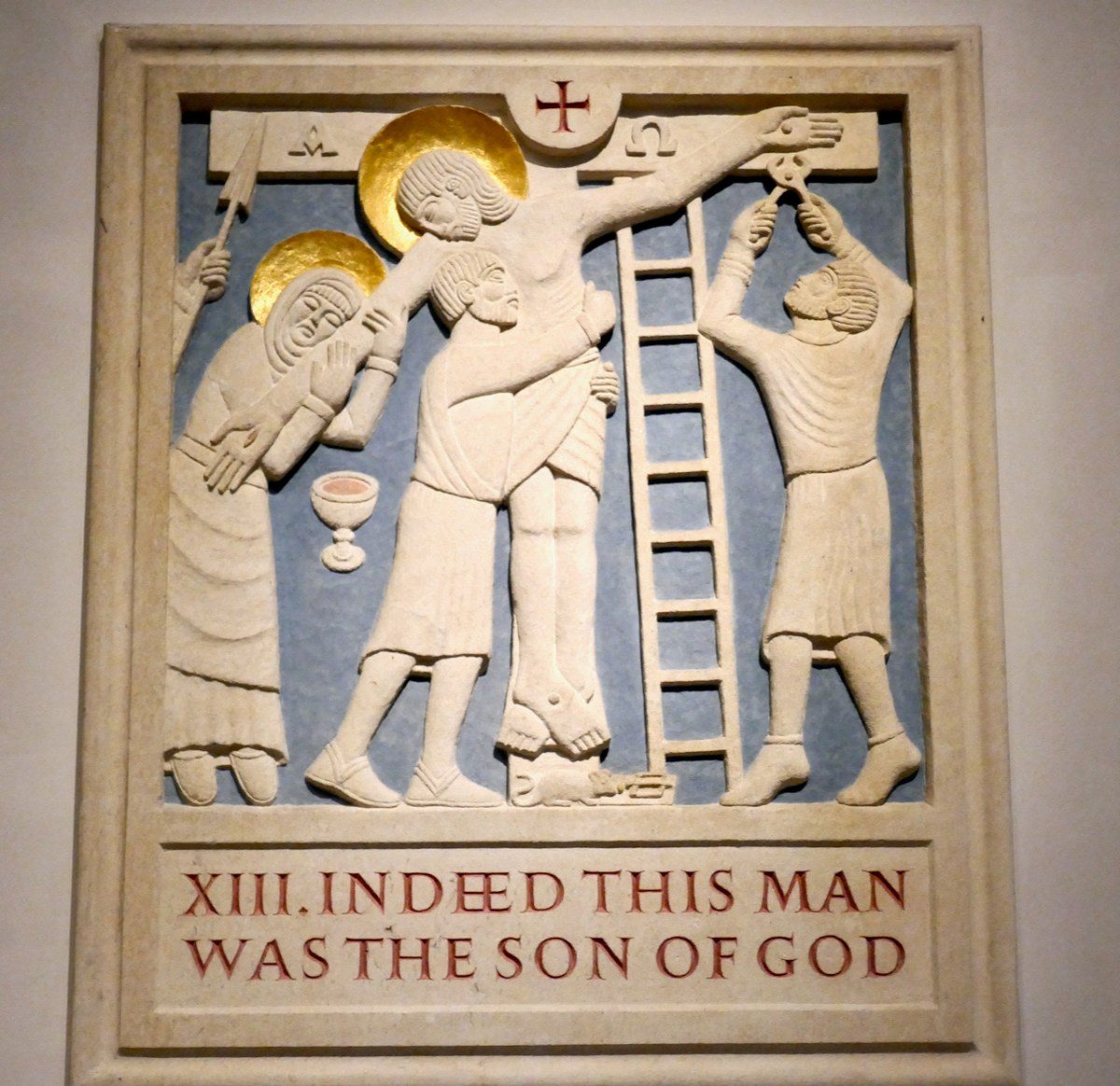

Galway Cathedral is a showcase for twentieth-century artists and all fourteen Stations were carved in portland stone by Gabriel Hayes. It took her eighteen years to complete them and she called them ‘the main work of my life.’

Certain architects – Liam McCormack, for example, or Richard Hurley – considered each aspect of their design and included specification for contemporary art. Some indeed, like Eamon Hedderman, worked closely with artists to plan a church holistically, incorporating the art into the integral fabric of the building. A magnificent example of this can be seen in the Church of the Irish Martyrs in Ballycane (Naas) where large-scale graphic stations designed by Michael Burke are surrounded by contemporary glass by George Walsh.

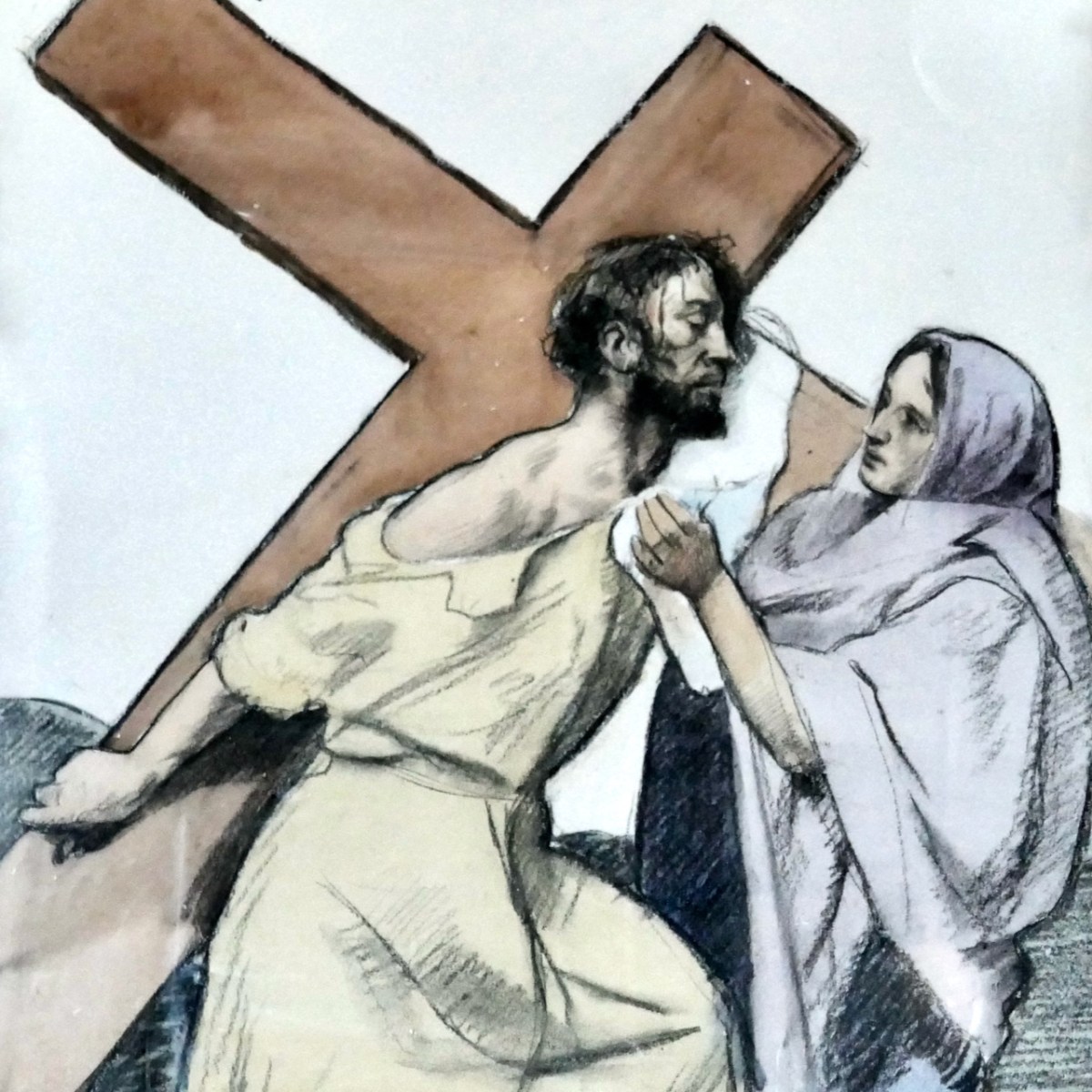

Many of the Irish artists familiar to us from the 20th century catalogues have contributed Stations to churches around the country – sometimes to the large cathedrals but often too to obscure country parishes where the priest (it was usually the priest) wanted something more than a standard imported set. Sean Keating‘s Stations for St John’s Church in Tralee (both images below) are arresting in their drama and strong character studies.

Stations come in many media and I have tried to show a variety in this post by well-known Irish artists. Bath stone was the medium of choice for Ken Thompson – the image below is of one of his stations for St Mel’s Cathedral in Longford. Below that is a Station from Ballywaltrim Church in Bray by the Breton/Irish Sculptor Yann Renard Goulet, although I am not sure what the material is.

Patrick Pye is more commonly associated with his stained glass windows for Irish churches, but his painted Stations for the Church of the Resurrection in Killarney (below) bring a quietly beautiful reflective focus to a contemporary interior.

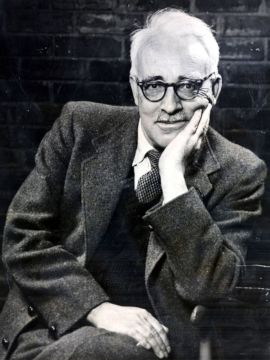

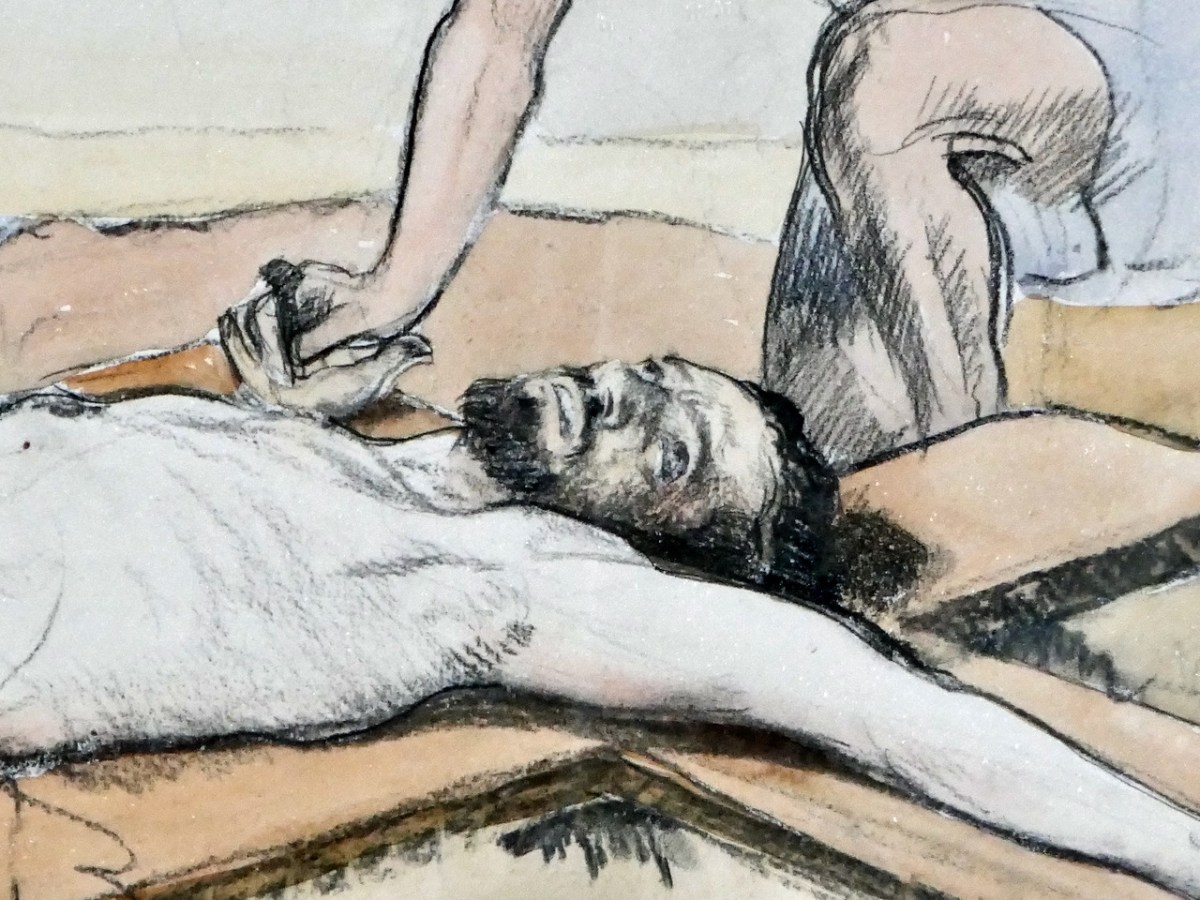

Sean O’Sullivan was known primarily as a portrait painter, but he also designed Stations, such as the ones below for the church in Newquay in Clare. Using only pencil and colour washes, he has produced powerfully emotive scenes (below).

Stations, however, are often unsigned and so our old friend Anon is responsible for many. A future post will include some of his or hers. The enamel Station below, for example, may be by Nell Murphy, but I can’t confirm this, so Anon it is, for the moment.

I am also planning a post on Stations done in stained glass – they are some really beautiful example, starting of course with Harry Clarke’s Lough Derg windows. But this post will start us off with some of the examples I have seen in churches around the country – let’s call it an Introduction to Irish Contemporary Stations. I’d love to hear from readers who have their own favourite set. And if anyone knows the artist responsible for the Stations in the Franciscan Church in Wexford (example below), do let me know!