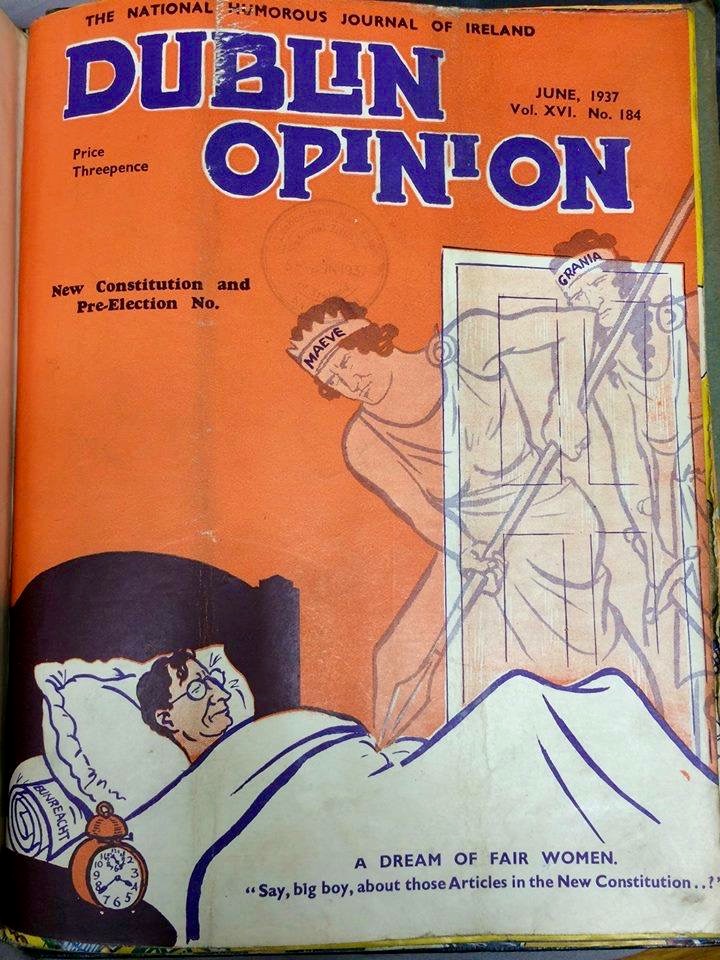

Henry Glassie’s book has been sitting on my shelves for 40 years, waiting to be dusted off and revisited. As a Mummer myself, I eagerly searched out any book on this then neglected subject, and was pleased to find this volume which concentrated on the Mumming tradition in Northern Ireland. It is written and illustrated by Henry Glassie, a Professor of Folklore at Indiana University Bloomington, and is the product of an extended field trip to County Fermanagh in the early 1970s.

Henry Glassie – born 1941 – has written many books about life and traditions in Ireland. His first was All Silver and no Brass, published by The Dolmen Press in 1976

…Winter nights in Ireland are black and long. A sharp wet wind often rises through them. Midwinter is a time to sit by the fire, safe in the family’s circle, waiting for the days to lengthen and warm. It is no time for venturing out into cold darkness. The ground is hard, the winds bitter. But for two and a half centuries, and possibly for many years before them, young men braved the chilly lanes, rambling as mummers from house to house, brightening country kitchens at Christmas with a comical drama. Their play, compact, poetical, and musical, introduced an antic crew and carried one character through death and resurrection…

(From the Preface to All Silver and no Brass by Henry Glassie)

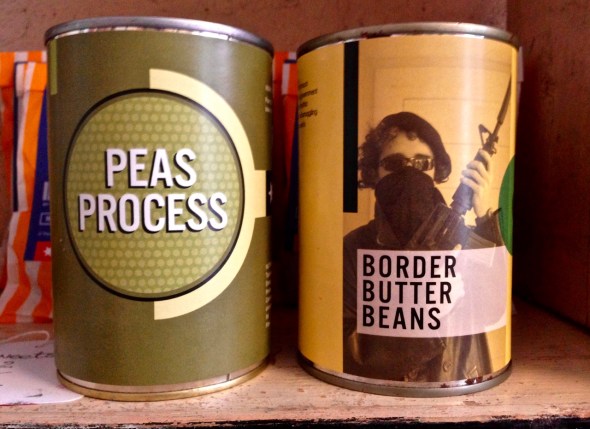

Glassie stayed in Ireland during the Troubles, and deliberately chose a community that was close to the upheavals of those days.

…Mumming was neither my project nor my goal. My project was the creation of an existentially grounded ethnography of people in trouble… We settled next to the barbed-wire bound barracks in the southwest Ulster town of Enniskillen, in the County Fermanagh, about twelve miles north and east of the burning border. I began quickly, luxuriously conducting my study on foot. I came to know every dog, bog, path and field in a small area south of the town, lying west of Upper Lough Erne, its waters as bright, its isles as green as promised in the old ballad of the Inniskilling Dragoon…

Enniskillen, from a photograph dated 1900, and Henry Glassie’s illustration of the mummers ‘Doin the Town’ as remembered in the 1970s

I like the way the book is set out. One section transcribes a number of conversations that Glassie has with people who remembered – and had been involved with – the mumming tradition.

…Most of the kitchens at the centers of those white houses were opened willingly, generously to me. My Americanness set me outside the local social categories, so I got on well with people of opposed political and religious persuasions. More of the people were Catholics than Protestants, more were men than women, more were old than young. Almost all had made courageous adaptations within the terrors that frame our lives. That was what interested me most: how daily life passed sanely, even artfully, despite armored cars hurtling down the country lanes, despite bombs that cracked the air and rattled the windows. I had forgotten all about mumming. Then one evening Mrs Cutler and I were chatting about Christmas and she mentioned the mummers’ arrival as the season’s high point. Suddenly excited, I asked if any of the play’s performers were still alive, and she listed people I knew well. All of them were men in their sixties and seventies who had begun to stand out in my thinking as exceptionally energetic, outgoing, and articulate. From that time on, I asked many questions about the drama, its performance, meaning, and purpose. I learned that the memory of mumming is cherished…

Upper picture – Wrenboys from Athea, Co Limerick, 1946 and below – ‘Mummers hunting the wren’ in Macroom, Co Cork, around 1950

Glassie talks at length to two brothers, Peter and Joseph Flanagan, who have very clear memories of taking part in the mumming.

“…We’d just take every house that we faced, whether we’d be admitted or not. We’d just take every house that we’d face. Of course, there was people on the other hand that wouldn’t admit them because it might frighten the youngsters, you see, or cause some confusion. That’s the way. That’s the way it goes now. So, You all stood at the door and…”

He twists and rapidly knocks five times on the table.

“…’who’s there?’

“…’Captain Mummer. Any admission?’ Yes, aye, or no: that was the way. ‘Any admittance for Captain Mummer and his men?’

“and if the person was pleased to admit you, well, they’d open the door. Throw it wide open for you.

“And Captain Mummer walked in.”

Peter moves quickly from his seat and down the kitchen. His heavy boots sound sharp on the floor. He closes the front door behind him, raps on it thrice, and re-enters. He strides ten feet into the kitchen and stands to deliver his lines, turning his torso to project to the audience assembled in a semi circle that runs from the front table past the hearth to the back table. Joe and I are fixed upon him…

“Here comes I, Captain Mummer and all me men.

Room, room, gallant room, gimmee room to rhyme,

Till I show you some diversion round these Christmas times.

Act of young, and act of age, the like of this were never acted on a stage.

If you don’t believe in what I say, enter in Beelzebub and he will clear the way.”

Frowning, Peter returns to his stool. It has been years since he has thought of the rhymes. “Let me see now,” he says, and sits repeating the speeches of Beelzebub and Prince George under his breath. Joe picks up the large turf out of the fire with the tongs and sets them at the front of the hearth. He sweeps the thick ashes off the iron to his side with a besom, places new turf against the backstone, and arranges the old coals next to them. The smoke and glow increase as the new turf ignite. Joe, too, went mumming, but he went out less often than Peter and cannot remember the part he played. He sits back as Peter starts in again…

Henry Glassie’s drawing of ‘how a mummer’s hat is made’ together with two examples from more recent times

Glassie’s writing goes on to describe the recollections of the play from those who undertook the performances. It is an invaluable record: his informants have now passed away. They would probably be surprised to know that their plays have not been lost: a new generation is performing in the north – and elsewhere on the island of Ireland. They would be even more surprised, perhaps, to learn that their own play breathes again: there is a Mummers Centre in Derrylin and the Aughakillymaude Community Mummers (Aughakillymaude translates as the wooden field of the wild dog) perform regularly in the area around Christmas time once more, while at other times they travel across Europe keeping the spirit of mumming in Ireland very much alive:

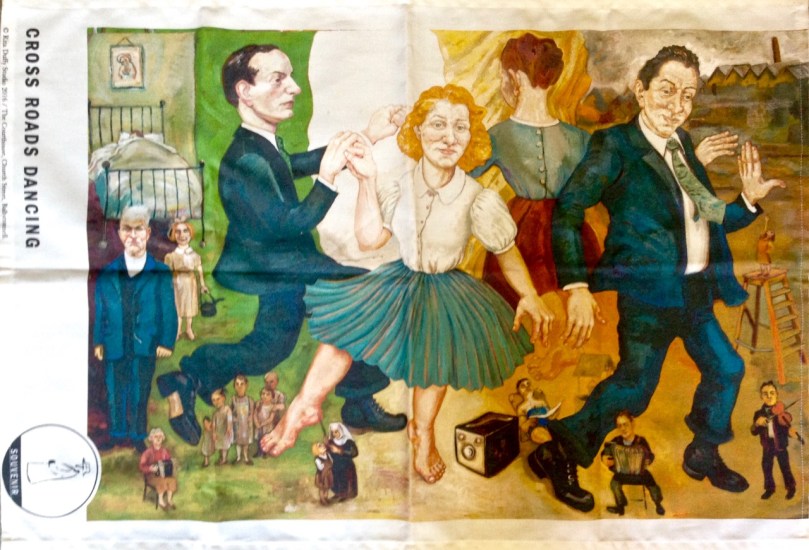

Aughakillymaude Community Mummers in full cry (above) and (below) Henry Glassie’s reconstruction of the performance before the hearth

Email link is under 'more' button.