. . . It is very seldomly violently cold here, and freezeth but little. There are commonly three or four frosts in one winter, but they are very short, seldom lasting more than three of four days together and with all their very worst, nothing so near so violent as in most other countries. But, how mild they ordinarily be, and how little subject to excessive cold. And as the cold in winter is moderate and tolerable, so is also the heat in summer; which is seldom so great, even in the hottest times of the year as to be greatly troublesome . . .

1726: A Natural History of Ireland in Three Parts by Gerard Boate, Gerard and Thomas Molyneaux

I was attracted to the early 18th century quote by Boate (first paragraph), because it certainly always seemed to be the case that Ireland has the perfect climate: never too cold and never too hot. In these days of global warming, maybe that’s less so than it used to be: we are experiencing long, cold and wet winters (here we are in mid May and we have to keep our fires burning!) and some scorching summer days when it’s exhausting to be out in the sun. Nevertheless, I believe we are fortunate not to suffer too much from unhealthy extremes – as yet.

Today’s post sees us travelling again with our frequent companions Amanda and Peter (above, with Finola). Remember my post from last week? For that expedition we stayed at Kells Bay House, in Co Kerry: Peter and Amanda organised that wonderful trip. We decided we couldn’t leave that sublime place until we had visited the Primaeval Forest there.

. . . Rowland Ponsonby Blennerhassett (1850-1928), grandson of Rowland Blennerhassett, married Mary Beatrice Armstrong from London in 1876 and is recorded as living at Kells. He extended the original Hollymount Cottage and renamed it Kells. They also kept a house at Hans Place, Chelsea, near to the Chelsea Physic Garden. Rowland Ponsonby is widely held responsible for making additions to the garden which still stand today. He established the Ladies Walled Garden adjacent to the front of the house for his wife Lady Mary, planted the Primeval Forest and laid out the pathways through the gardens . . .

The History of Kells Bay House & Gardens

Helen M Haugh 2015

One of the principal attractions of the gardens at Kells Bay – and the Primaeval Forest – is a series of sculptures carved from tree fragments, commenced in 2011, by Kerry sculptor Pieter Koning. Here is a striking portrait of that artist by photographer David Molloy:

David Molloy: A portrait of the Artist Pieter Koning, 2017 © David Molloy

The Dinosaur sculptures have blended well into the natural landscape over the years: we were delighted with them!

In addition to the Dinosaurs, which are well worth an exploration (I have only shown a few here to tantalise you into a visit!), there is a tree-fern forest planted by Blennerhassett, and spectacularly enhanced by the present owner, Billy Alexander, who has been awarded a Gold Medal at Chelsea Flower Show for his Kells Bay Gardens ‘mirocosm’. There are plenty of landscaping features old and new, and a ‘Sky Walk’ rope bridge, which is quite challenging.

Finola and I are at odds about this species: Gunnera manicata. Finola sees them springing up in the countryside where they ‘don’t belong’ – they originate in South America and are now spreading wildly, particularly here in the west of Ireland. Gunnera is listed on the Third Schedule of the EU Habitats Regulations which makes it an offence under Regulation 49 …to plant, disperse, allow or cause to grow this plant in the Republic of Ireland… So I can see Finola’s viewpoint. But I have always admired them. They grow so fast that you can almost see them getting bigger if you stand and stare for a few minutes. In this context, at Kells Bay House, they are part of an exotic collection dating from the 1800s, and therefore excused (says I).

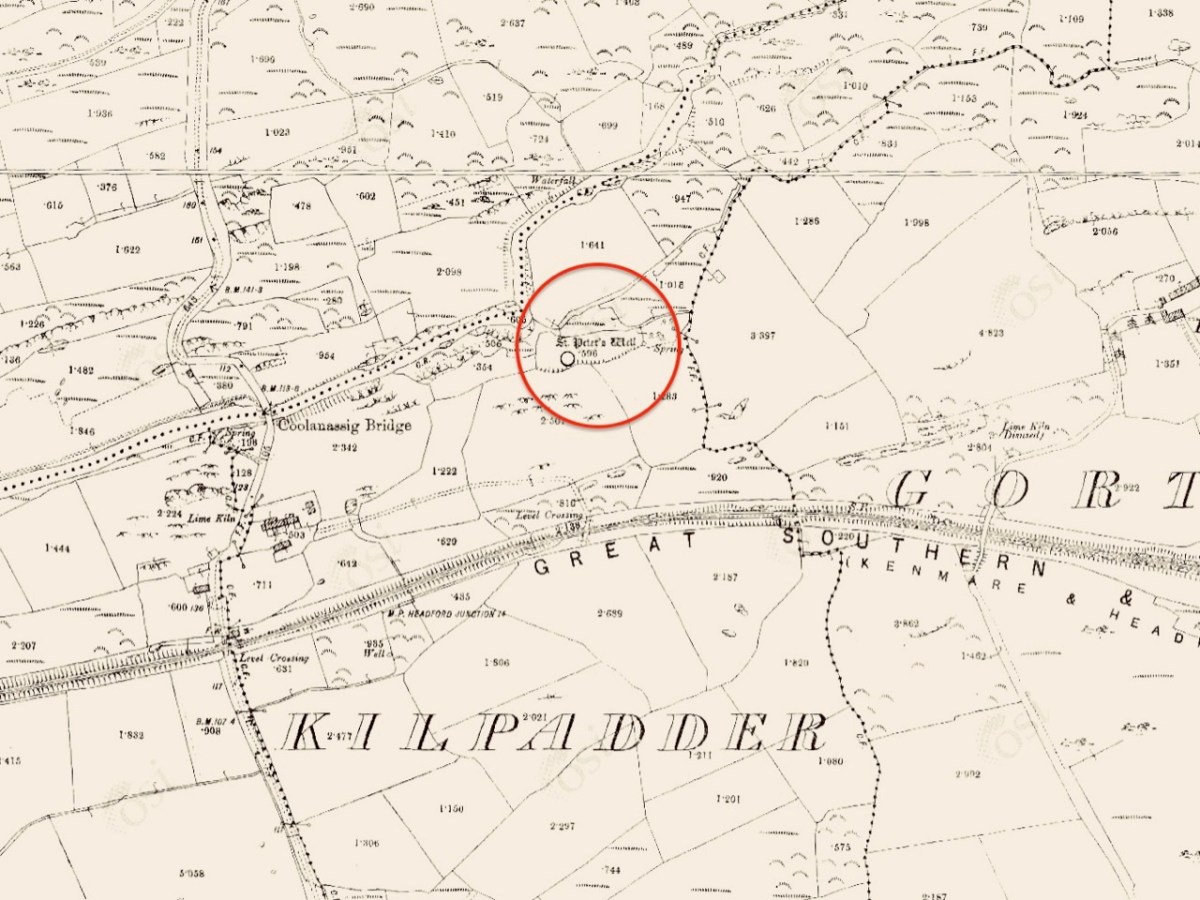

I hope you will agree that Kells Bay House and Gardens is a ‘must see’ destination. And it’s well worth more than one visit. Include it – as we did – in a tour of landscape, archaeology and Holy Wells. The county of Kerry has so much to offer!