I wanted to explore the Ilen River: that’s pronounced eye-len, and it comes from the Gaelic An Aighlinn. ‘Aighlinn’ is an Irish name, the equivalent of Eileen in English, but it is also said to have a meaning when it relates to water: ‘the way that moonlight reflects on water . . .‘ We’ll keep a lookout for the moonlight, but our first expedition was carried out on a glorious late November day, absolutely calm and with clear, deep blue skies: the morning reflections were perfect.

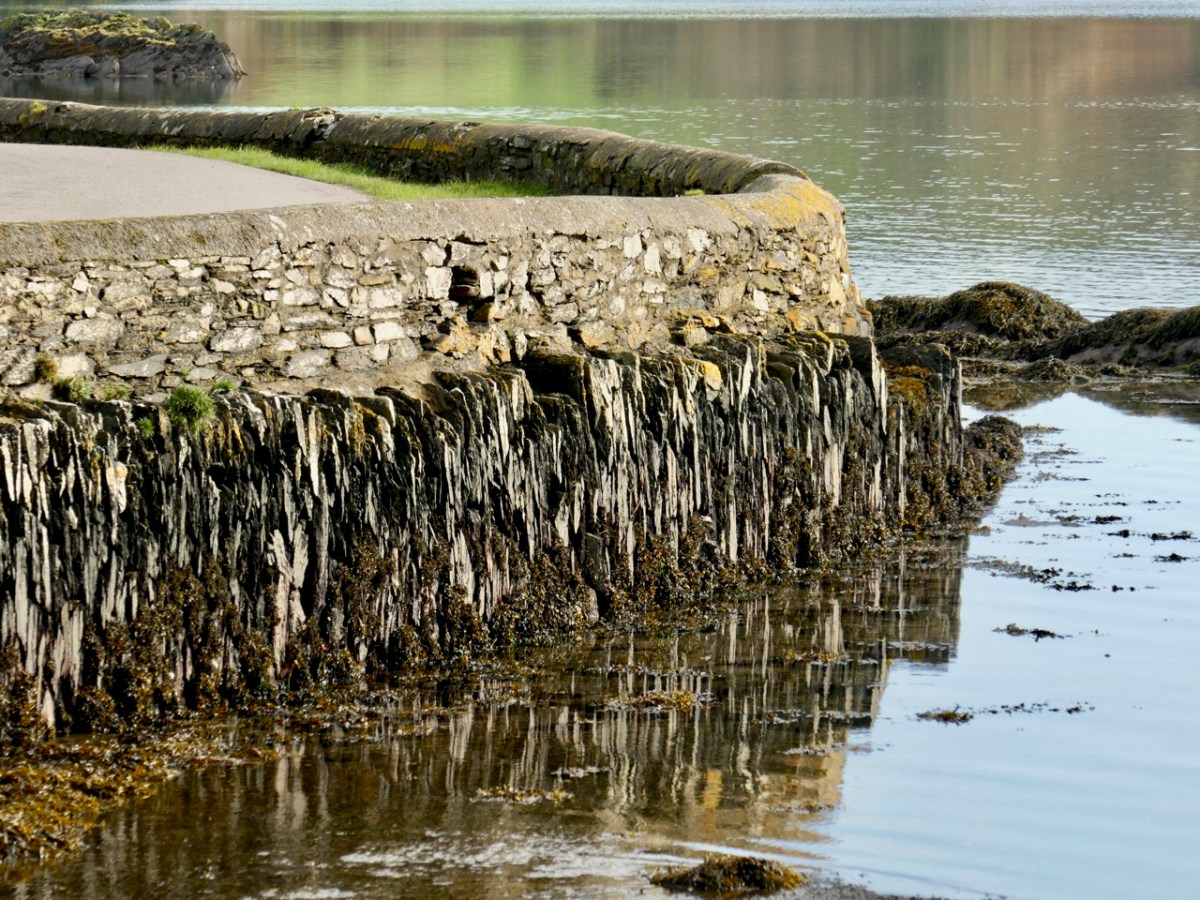

The header and the picture above are both taken in Skibbereen, as good a place as any to begin our wanderings. The town is built on the river and was once a water transport hub: in the early 19th century boats of up to 200 tons could navigate to Oldcourt, within two miles of the town centre. From there goods were transferred into ‘lighters’ (unpowered barges) and then brought into the town where there were no less than five quays, warehouses and a Customs House. Unfortunately, low bridges now prevent navigation.

This aerial photograph dates from a few years ago, but it’s useful to show how Skibbereen has developed along the south bank of the river. At the Town Wharf, or Levis’ Quay, you can still see old stone steps leading down to the water’s edge, once a hive of activity with lighters loading and unloading. The nineteenth century brought engineering advances, with railway connection to Dunmanway, Bandon and Cork. The station – marked above as the ‘Ilen Valley Railway Terminus’ opened in 1877. Later, the Baltimore Extension Line continued south over a smart new steel bridge, built in 1892.

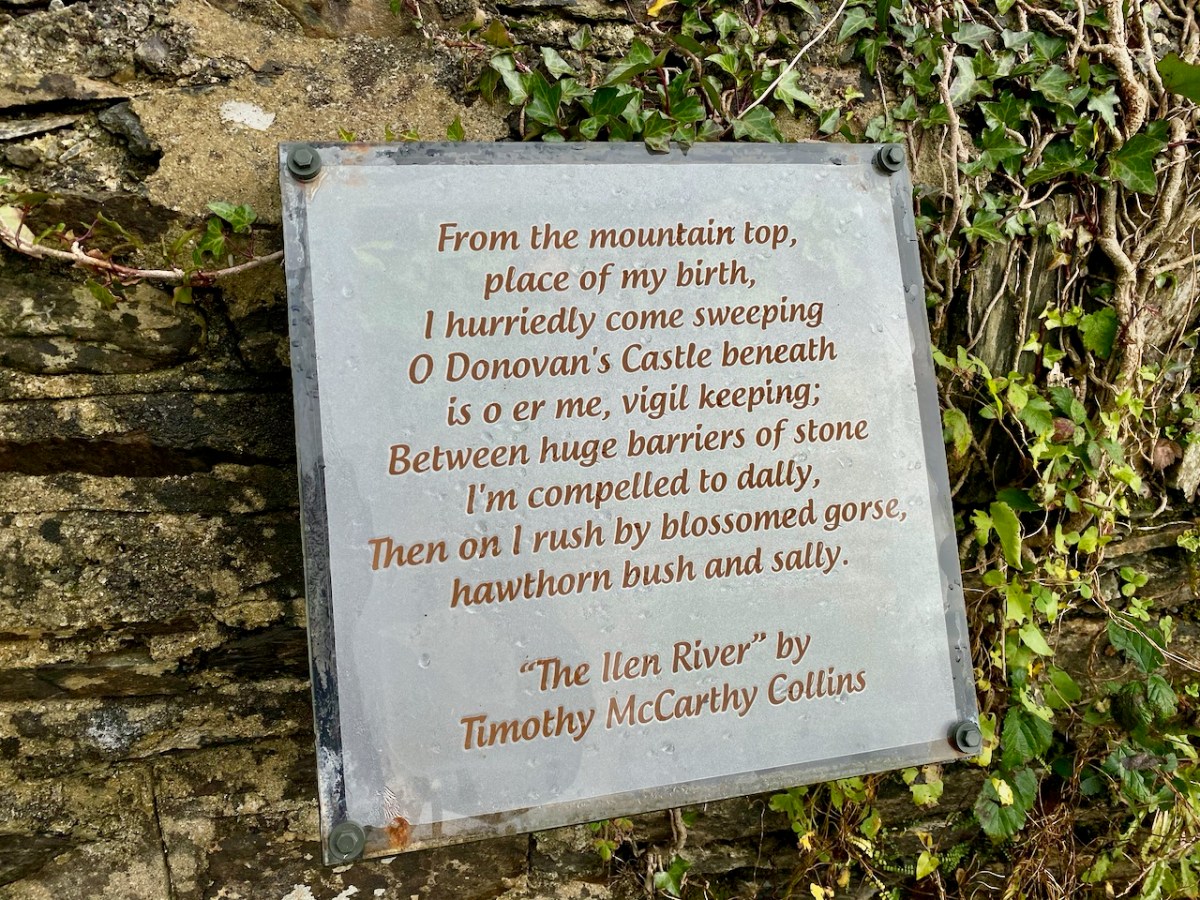

From Skibbereen there is plenty of the river to explore both south (to the estuary) and north. It’s our ambition – when travel restrictions ease – to find the source of the river on Mullaghmesha Mountain, which we could see in the far distance beyond Castle Donovan on our walk last week. That might have to wait anyway, as climbing that mountain is not recommended in the winter months because of rough conditions underfoot, but keep watching – we will get there!

The dancing of a mountain stream may be as entrancing as a ballet, but the quiet of an age-old river is like the slow turning of pages in a well-loved book . . .

Robert Gibbings – TILL I END MY SONG

One of our great heroes is Cork-born writer and illustrator Robert Gibbings. He was an explorer of rivers, making books of Cork’s River Lee, the Welsh Wye and – most famously – Sweet Thames Run Softly. In homage to him I’m calling these posts Sweet Ilen: I don’t think he will mind. Sadly, I haven’t his artistic talents but I’ll do my best with words and photographs.

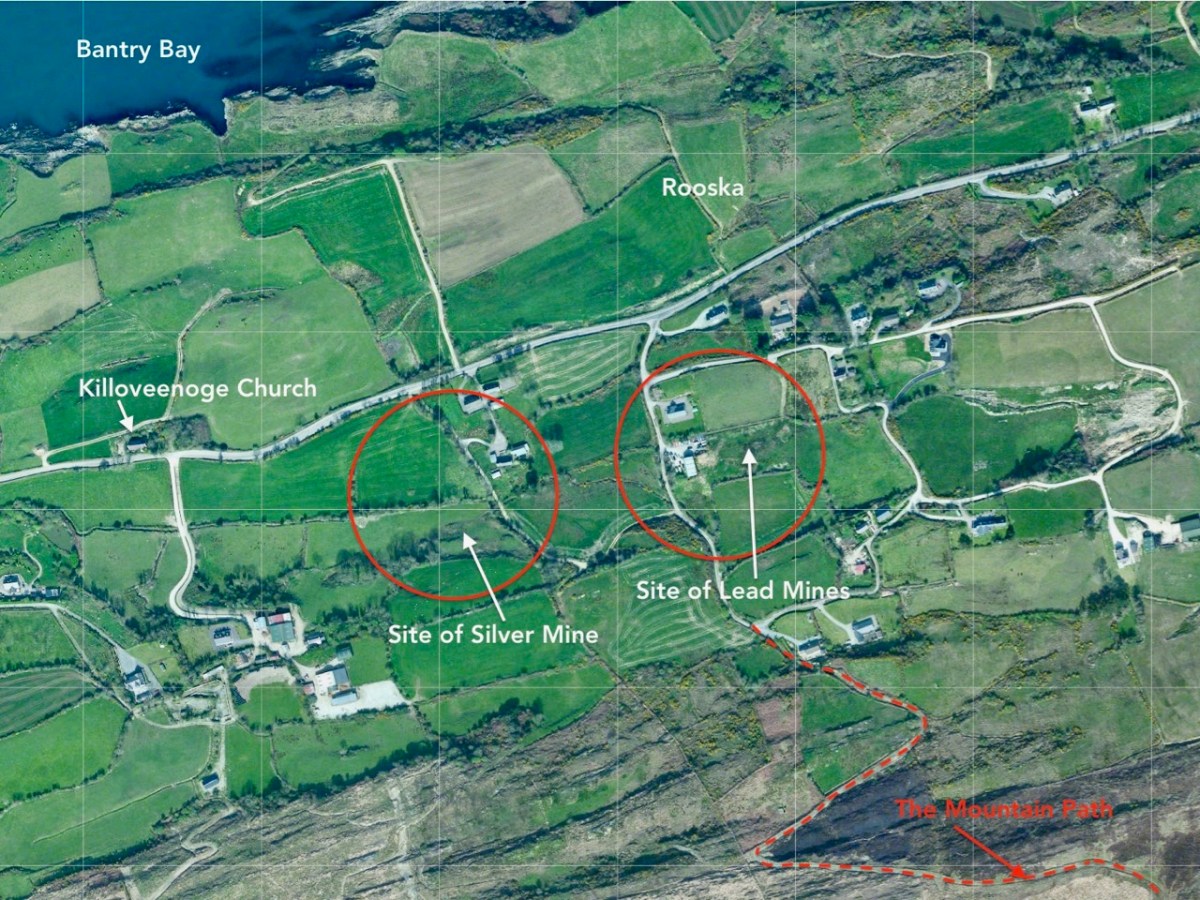

The upper picture looks from the West Cork Hotel upstream towards the town: the Town Wharf is just around the corner; the steps in the foreground mark the beginning of the Ilen River Blueway – you will embark here if you take a kayak trip down to Baltimore. Leaving Skibbereen behind, we soon realised that the Ilen is a secretive waterway: much of its course is hidden away and runs in quiet backwaters distant from habitation and modern life. It’s only at the crossing points like the one above, near Hollybrook, that the river briefly reveals itself to us, although anglers have private pathways known only to themselves: we caught tantalising glimpses of their occupancy through the tree cover on some remoter banks.

A well-placed seat with a view (upper picture) on the angler’s path below Ballyhilty Bridge. Close by (lower picture) is a small farm accommodation bridge which is also giving anglers access to the further bank. Ballyhilty bridge itself is a real discovery. It’s easy to drive over it without realising the substantial structure which carries the road:

The only description I could find of this substantial structure is a record in the Archaeology Ireland National Monuments site which describes it as ‘a hump back three-arch road bridge over the Ilen River in the townland of Gortnamucklagh’. The parallel entry in the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage describes it as ‘bridge 1760 – 1800’, and says no more. But I think it worthy of detailed consideration: it’s a massive, dressed stone structure which has been reinforced with iron plates. The central opening is raised to a height which would almost lead us to think that it was once a navigation arch, although there are no records to support this. On the west side are some flood relief culverts of unusual construction:

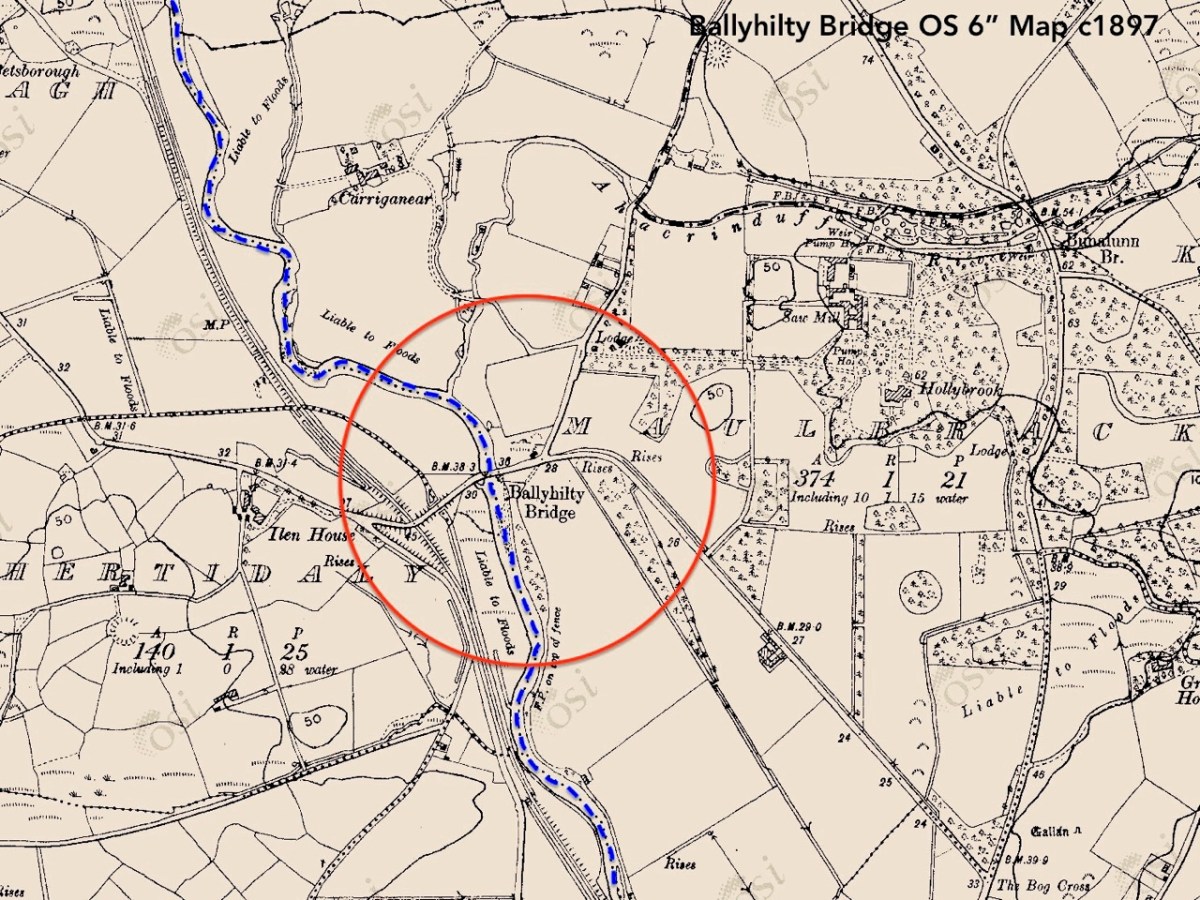

The form of these remind me of a bridge we encountered on the Fastnet Trails close to Toormore in 2018: here’s the post. At that time I pondered on how old the Toormore structure was likely to be. I’m asking myself the same question on this one. The early OS map might give us a clue:

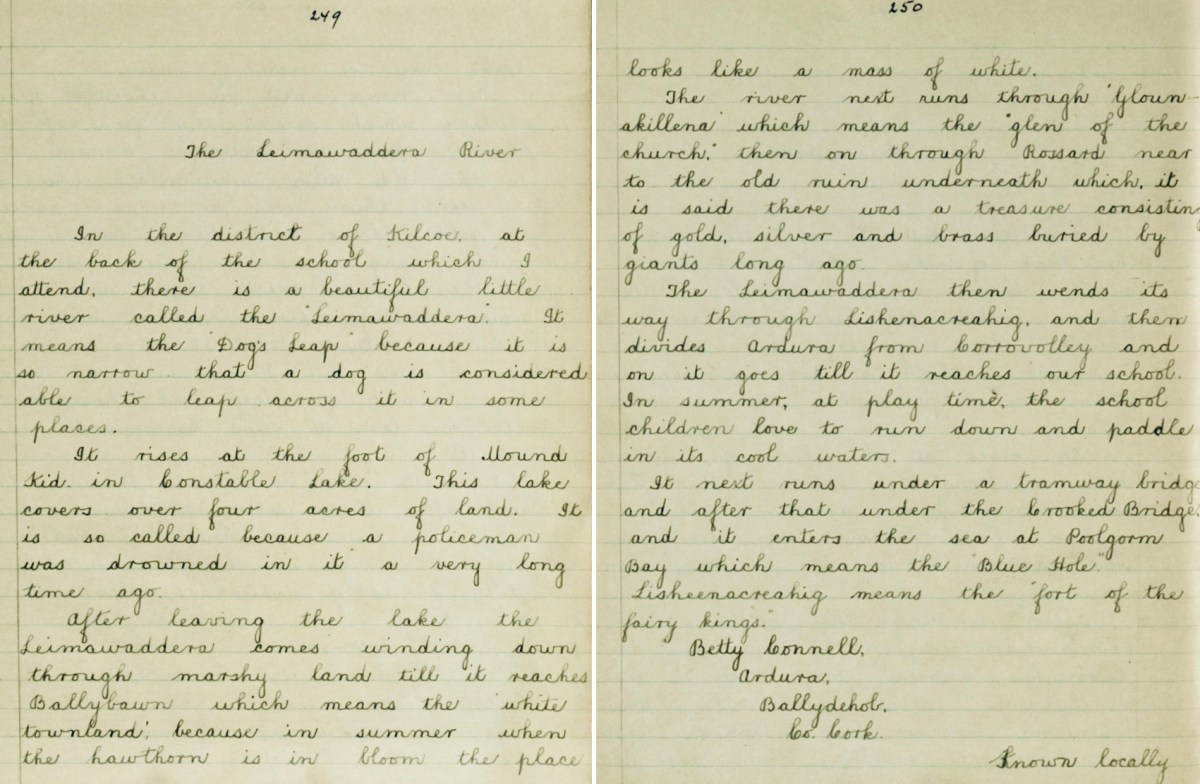

This is from the late 19th century 25″ map: you can see the railway line on the west heading out of Skibbereen towards Drimoleague, where it met with the Cork, Bandon and Bantry lines. But on the east side of the river is a very large estate: Hollybrook, in the townland of Maulbrack. Hollybrook House has a long history, encompassing families such as The O’Donovan, Bechers and Townsends. Nowhere can I find a date for the original house (now replaced), but I have found this:

At the time of Griffith’s Valuation, John Beecher held two substantial properties in fee at Maulbrack. They were purchased in 1703 by Henry Beecher from the trustees for forfeited estates . . .

NUI GALWAY – CONNACHT AND MUNSTER LANDED ESTATES DATABASE

These properties were therefore in existence before 1703: it would be reasonable to assume their date could be well before this. I would suggest that the bridge at Ballyhilty was built in the 1600s, to ensure good access to the estate at Maulbrack. This would make it a truly historic structure, worthy of prominent commentary and protection.

On such idyllic days for exploration it’s not always easy to remind ourselves of the power of this river: it’s no humble stream. Here’s a screenshot of a drone video by Garry Minihane Photography which shows this same stretch – at Ballyhilty – in full flood: the adjacent roads are set just high enough to be clear of all but the fiercest of deluges! Skibbereen is in the distance.

I’m thinking that the journey so far is sufficient for this week’s post; next time we will travel further north, penetrating even more into the uplands of the Ilen as we set our path towards the source. It’s not a huge river, only 34 km in total. It’s instructive for us that our West Cork terrain is quite small scale: within that 30-odd kilometres we have the contrast of a mountain stream falling from the high places and gathering enough tributaries to feed the tidal reaches which we also have yet to discover on our coasts.