We’ve had a book on our shelves for years, and it has been overlooked: The Islands of Ireland by Thomas H Mason.

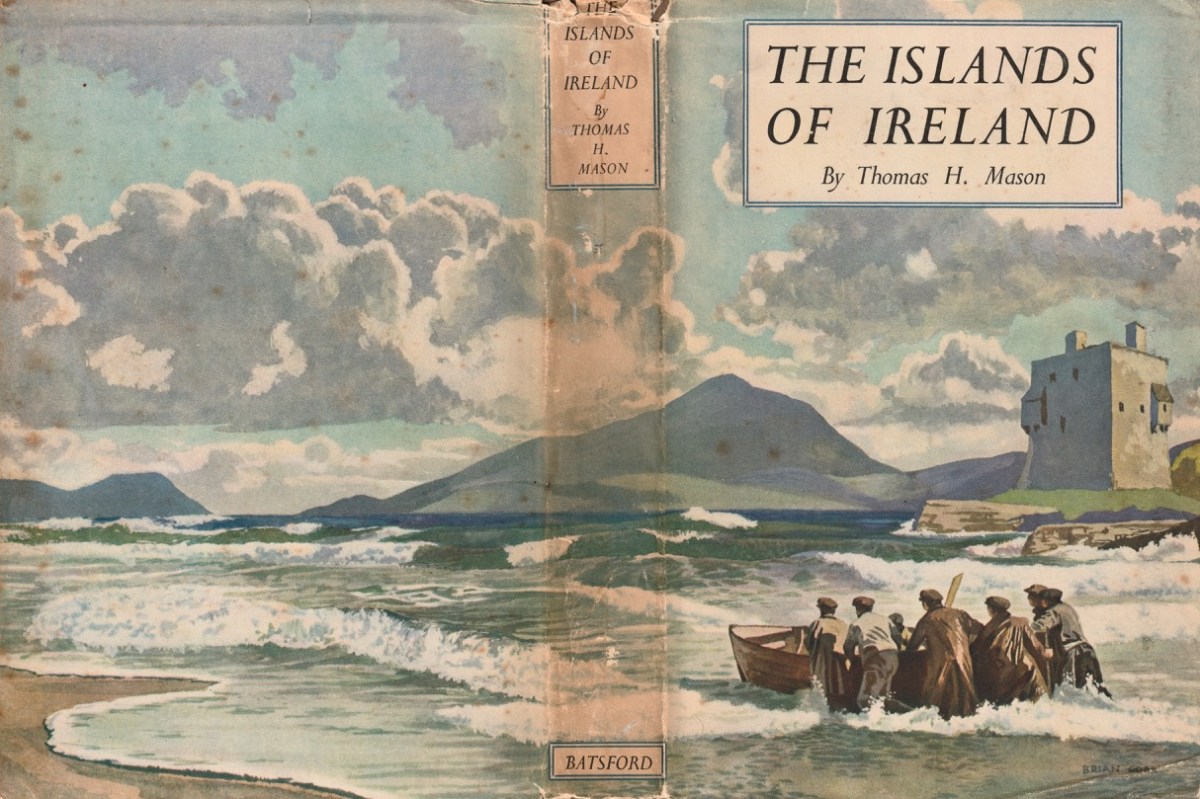

Here’s the wonderful cover, and anyone who knows their books will be aware that it’s published by Batsford, and has a cover painted by Brian Cook. Our copy is well weathered, but still recognisable as the work of Cook: the graphics are very distinctive.

This is Brian Cook – in fact he is known as Sir Brian Caldwell Cook Batsford, and he lived from 1910 to 1991. He added the name ‘Batsford’ when he became Chairman of the publishing firm: his mother was a Batsford and his Uncle Harry headed up the firm for many years, although it had been founded back in 1843. Those of my generation will remember the very distinctive cover illustrations, all produced by Brian – with a mid-20th century style – and many still used to this day.

Another of Brian Cook’s book covers – showing the North Devon coast, not far from where I lived for many years. The Batsford Countryside, History and Heritage series included The Spirit of Ireland by Lynn Doyle (1939), and The Face of Ireland by Michael Floyd (1937). Many of the early books are now considered collector’s items, so we are fortunate to have The Islands of Ireland close at hand.

Brian Cook and his daughter, Sophie, in March 1970 (Evening Standard Library). Having had a quick run-down on the cover artist, let us now look more closely at the writer,Thomas H Mason: an article in the Irish Times – Oct 22 2003 – provides a background to the Mason family. They go back to the early 1700s and are described as ‘The oldest family business in the State’. When Seacombe Mason set up his own business at 8 Arran Quay, Dublin,

. . . His list of sale items included “telescopes, glasses, microscopes, concave and opera glasses, celestial and terrestrial globes of all sizes, electrical machines with apparatus – goggles for protecting the eyes from dust or wind, ditto for children with the squint . . .

Irish Times

The descendants of this early business – now Mason Technology – are based in Dublin, Cork and Belfast, but it’s Thomas H who interests us. Thomas Holmes Mason was born in 1877 and died in 1958, having moved the company into a new sphere. His grandson, Stan explains:

. . . In the late 1890s he introduced photography to the business in the form of picture postcards. We went on to become the biggest producer of picture postcards in Ireland, right up until the 1940s. My grandfather was interested in archaeology, ornithology, historical sites on the islands off Ireland, interests which brought him all over the country with his full-plate camera. He built up a huge and very fine collection of pictures which, unfortunately, were destroyed by fire in 1963 . . .

Irish Times

Examples of the photography of Thomas H Mason, also the header: views of Clare Island, Co Mayo. Initially, the ‘Islands’ book seems slightly disappointing: we would like to have seen something of the islands in our part of the west: Roaringwater Bay. But these do not get a mention!

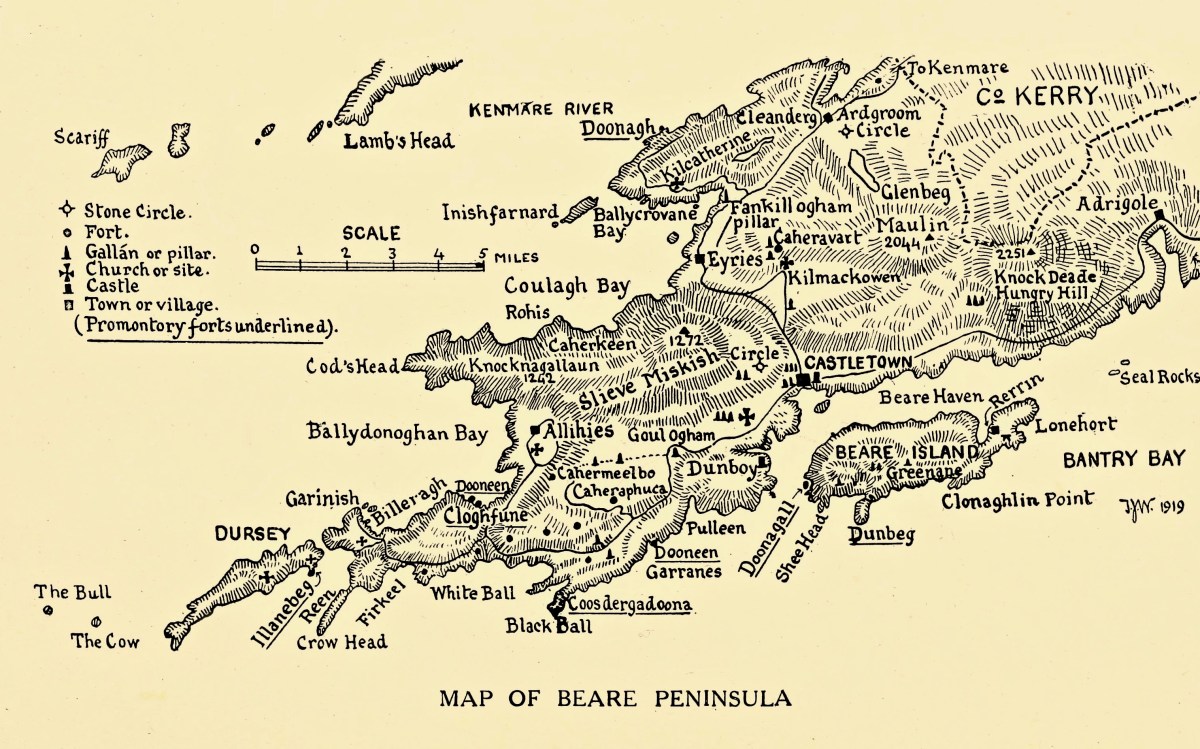

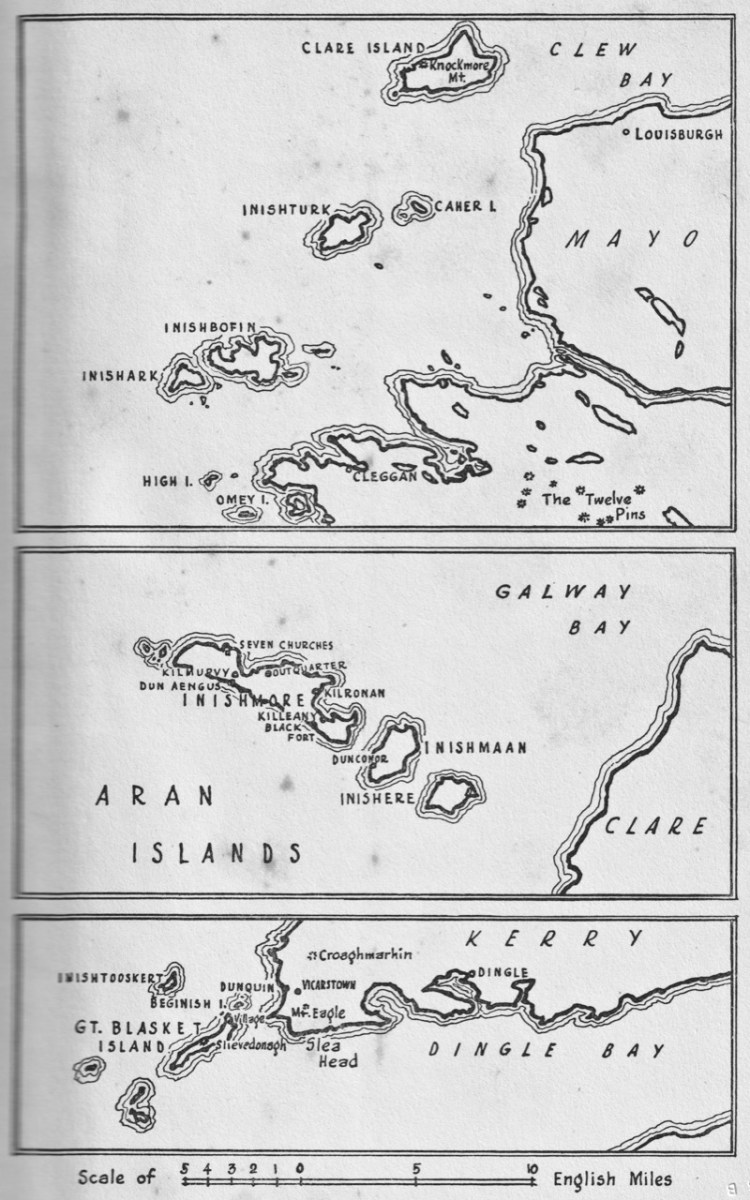

Key: the map in the book, which covers islands in Mayo, Clare and Kerry. Perhaps a further volume might have set out to include the south-west? But – what Mason has given us is a fascinating photographic insight into life on the Blaskets when they were still inhabited; and sketches of the worlds of the Aran Islands and the Mayo islands from nigh on ninety years ago.

These two photographs show Clare Island during Mason’s visits in the 1930s. Note the castle, above, also included on Brian Cook’s cover painting. That is -of course – the headquarters of Gráinne Mhaol, probably better known as Grace O’Malley (1530 – 1603) – Ireland’s Lady of the Sea. But her story is far too long to tell here: she will have a post of her own in the future! Granuaile Castle overlooks Clew Bay, in Co Mayo.

The last image for today, from Thomas H Mason: Blasket Island Cottage. This is an invaluable record of a remote way of life: perhaps ‘timeless’ – apart from the clock in the alcove by the fireplace!

Look out for more from this writer and photographer – and more about ‘the Lady’ too!