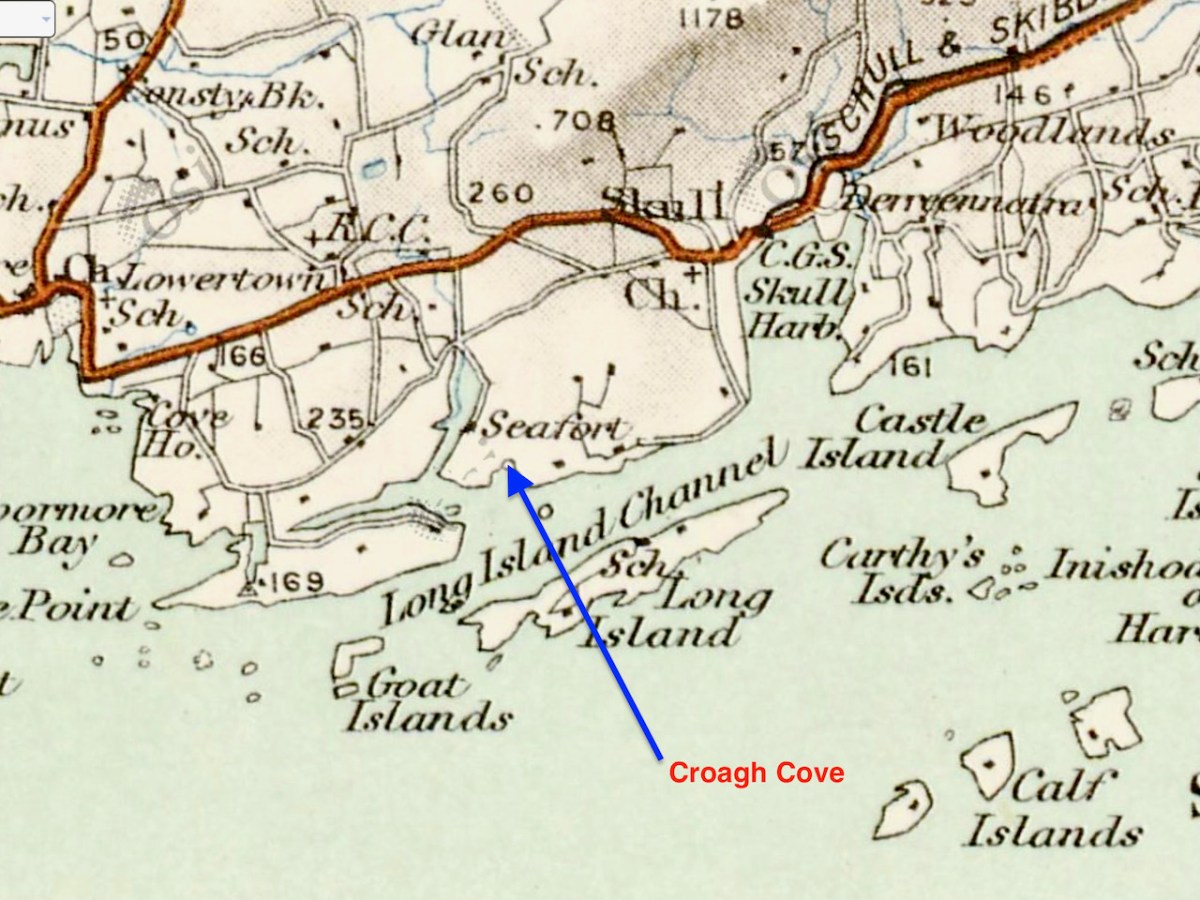

What better place to spend Easter Day than at the ‘Easter end’ of Long Island? We can see the island – out there in Roaringwater Bay – from our home here at Nead an Iolair. The lighthouse on the end of the island faces us – and winks through the night with the character of 3 quick flashes every 10 seconds. The narrow headland on which it stands bears the name ‘Copper Point’ – and so does the lighthouse.

This aerial view shows Long Island in its context – a part of Roaringwater Bay and its ‘Carbery’s Hundred Islands’. Its neighbours to the east are Castle Island and Horse Island – all in our view – (that’s our view, below).

A closer aerial view of the island, above. It’s accessed by a regular ferry which leaves Colla Pier, a short distance from Schull town. The ferry arrives at Long Island Pier: there it is, on the pier (below).

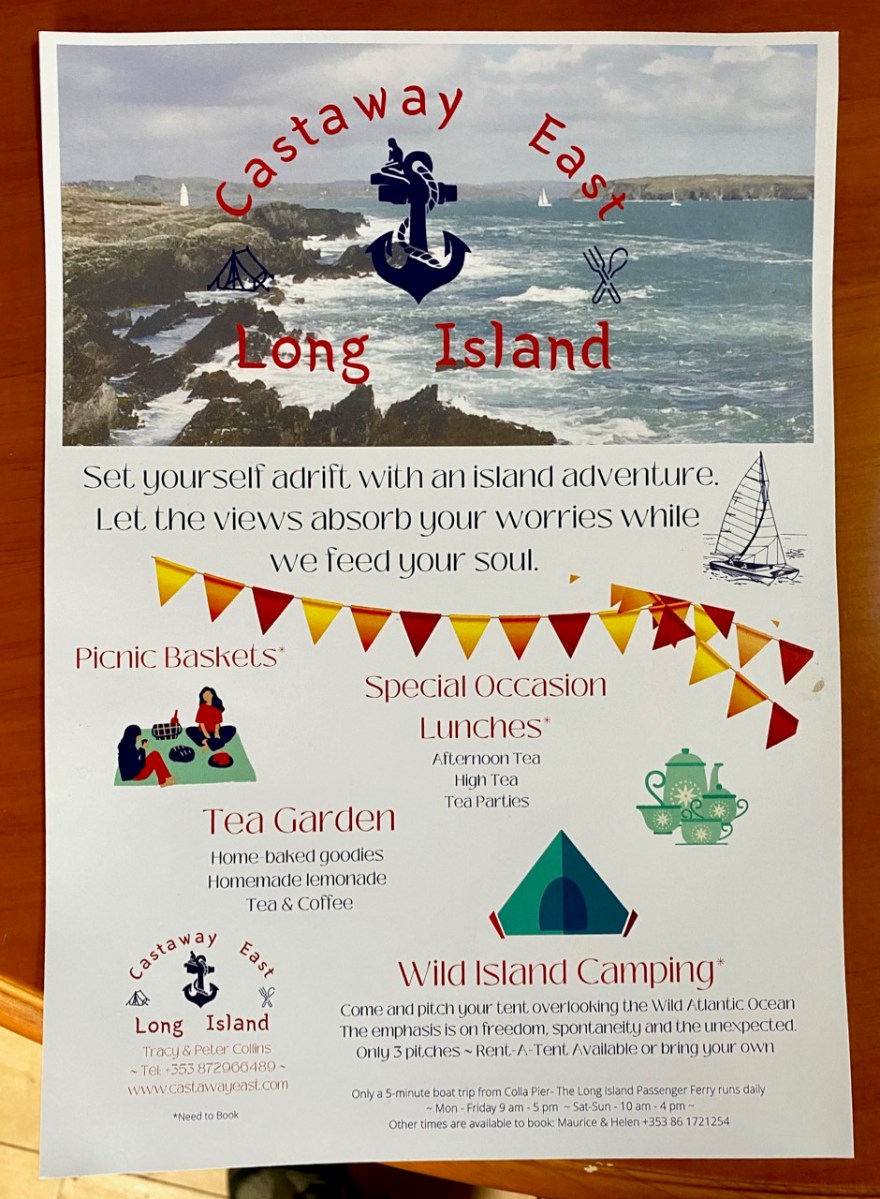

Our destination on this Easter Sunday was Castaway East – the furthest house on the ‘Easter’ end of the island. We have taken you there before, when we organised a Mad Hatter’s Tea Party in July of last year. The hosts there are Tracy and Peter, who served us brilliantly for that occasion, and also for the Wildflower Walks which Finola led last June: the Castaway crew provided a superb picnic for everyone, delivered to us at the island’s western end. This time we decided that we would test Tracy and Peter’s skills by ordering up an Easter Sunday lunch to celebrate a ‘special’ birthday for our good friend, Peter Clarke.

Amanda Clarke, Finola and birthday boy Peter, looking forward to a morning coffee (with delicious Easter treats) after arriving at Castaway East. We had an upstairs room in the Castaway house, with a good view over the island. Before lunch we had an opportunity to explore part of the island we had never been to before, heading down to Copper Point.

Why is it called ‘Copper Point’? Because there was a copper mine close by, one of many such enterprises that were seen in West Cork in the nineteenth century. Explorations on the island were started in the 1840s by the Cornish mining engineer Captain William Thomas: he wrote a Roaringwater Journal post for us a couple of years ago! William sank a trial shaft for 10 fathoms (60 feet) and extended a level south from this shaft for 3 fathoms. No metal bearing lode was found, and the mine was abandoned. Traces of these workings can still be seen not far from the lighthouse. It’s slightly ironic, perhaps, that the name ‘Copper Point’ arrived from somewhere and stuck.

It’s a wild landscape – but very beautiful and imbued with atmosphere. We certainly worked up a good appetite while on our morning walk, and returned to the house with great expectations.

All those expectations were far exceeded when we sat down to our meal. We had a room to ourselves, attractively furnished and comfortable, with a welcome wood-burning stove on the go in one corner. Tracy and Peter have spent considerable time and energy upgrading what was a very run-down cottage, and have used locally available materials with impressive imagination.

Tracy – in charge of the culinary delights – had worked out a menu which was entirely tailored to our various tastes (and dislikes) – and it was brilliant! All the courses were exemplary.

The main was a Sunday roast to make your mouths water… Fillets of pork for the three of us who are not vegetarian, and a miraculous stuffed filo pastry pie for Amanda. The accompanying vegetables were prepared without any meaty elements – so we could all savour them in equal measure.

Peter was delighted with every aspect of his celebratory meal – we all were! The choux bun dessert was unbelievable; not a morsel was left behind. The riches never stopped: for our after-dinner coffee we went outside to the terrace-with-a-view and enjoyed home-made fondants and biscuits.

I think you’ve got the message… Sunday lunch at Castaway East is a very special experience indeed. Combine it with a good walk on a beautiful and atmospheric West Cork island and you will have a day you will always remember. If you want the experience for yourselves give Tracy and Peter a shout: they will be delighted to organise it for you.

Contact Tracy & Peter Collins on +353 872966489 or email simplytracy@icloud.com – They also have a campsite!