West Cork artist Keith Payne is currently the subject of an exhibition in the Blue House Gallery, Schull. Get to see it if you can! We featured Keith on our Journal back in 2018, when he had an exhibition in the Burren College of Art Gallery in Ballyvaughan, Co Clare. But he also contributed some amazing work to our own Rock Art exhibition at the Cork Public Museum in 2015.

That’s Keith’s painting – based on the Rock Art at Derreenaclogh, close to where we live in West Cork – on the right, above. It was in the Clare exhibition and also our Cork Public Museum exhibition.

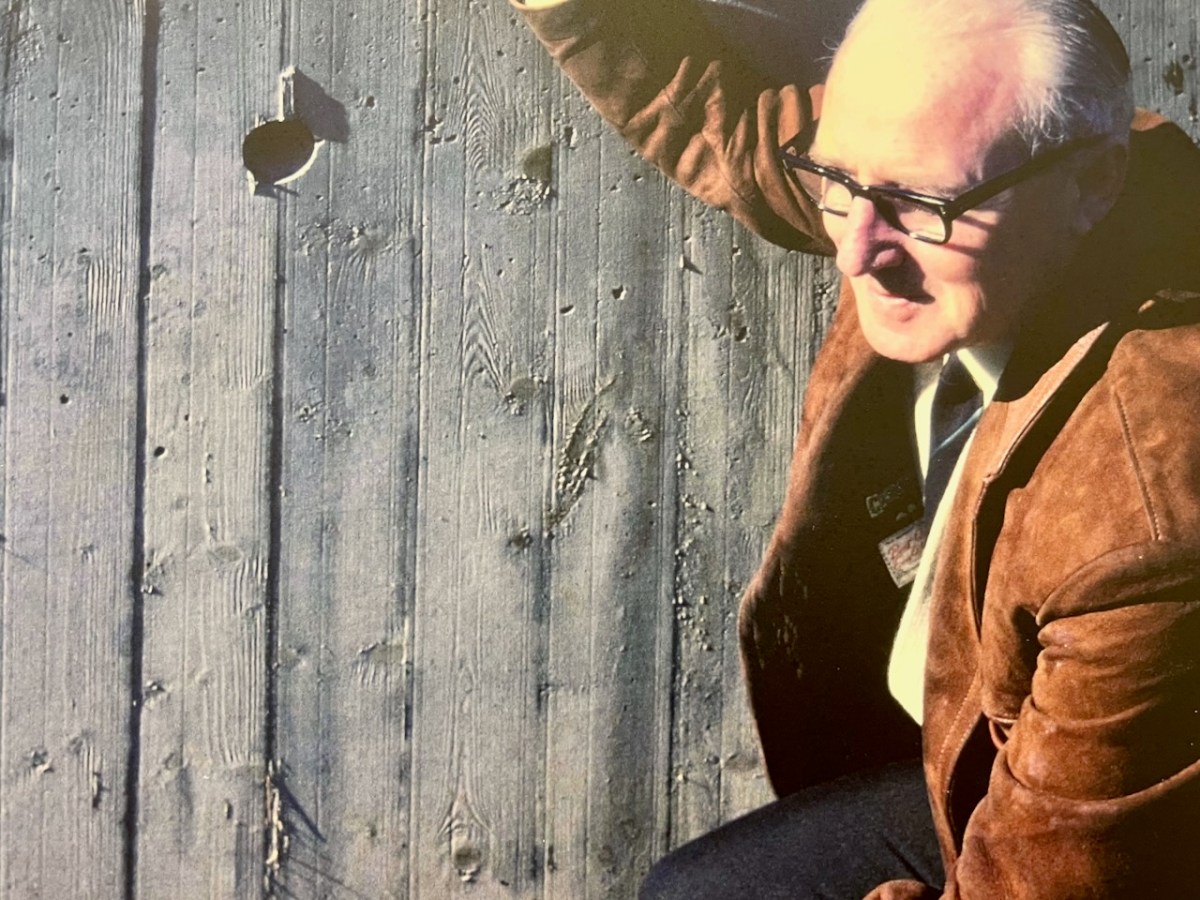

You have the opportunity to see the current show in Schull, as it’s on until Culture Night (Friday 22 September 2023). Early Marks is “…a study of the beginnings of art and the possible source of a prehistoric worldwide visual language…” That’s a huge subject, and Keith (below) tackles it with large, assured and spirited images.

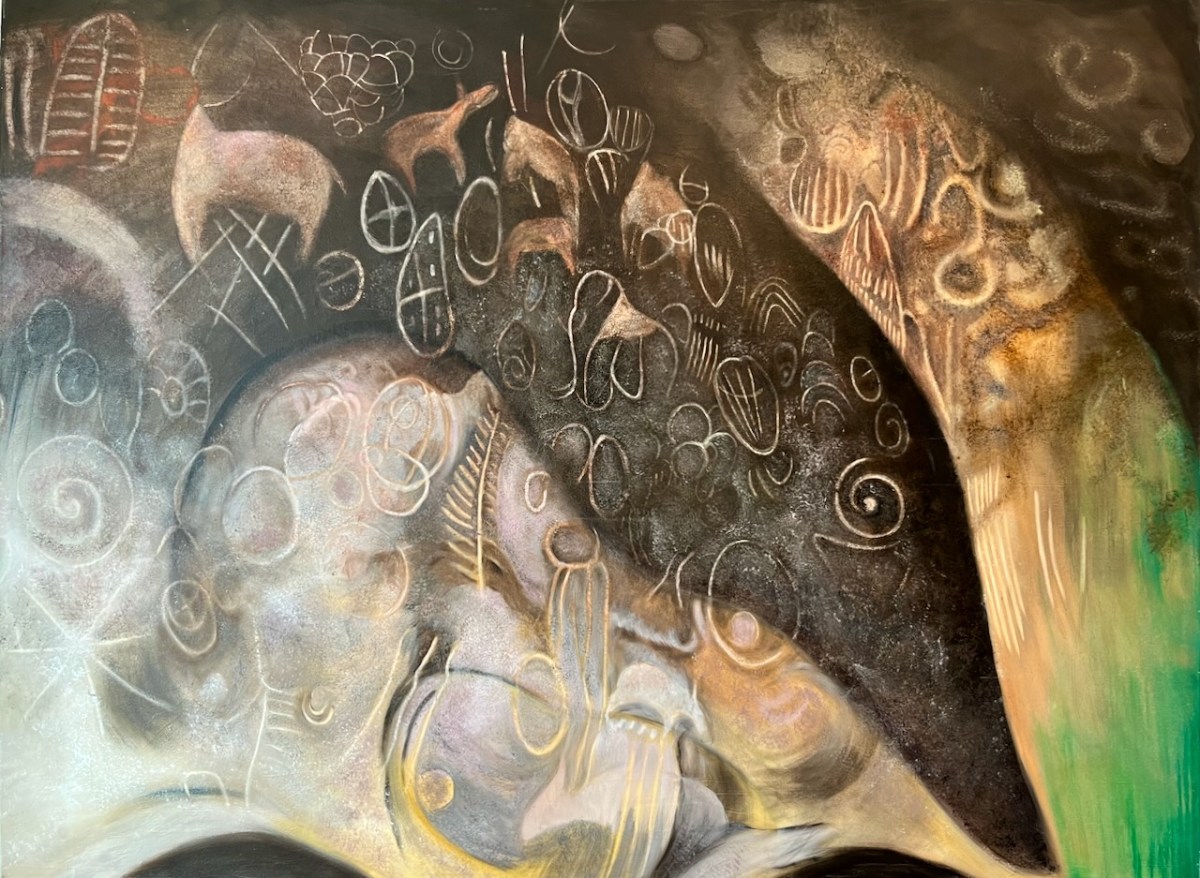

. . . There is no Time associated with any of these works, as Time is a construct invented long after the images on exhibition. Hunter-Gatherers, the makers of Early Marks, lived in a visionary state now lost to western civilisation . . . The language of Early marks consists of imagery, symbols and patterns that have been left in the physical world but created in the ‘other world’ . . . Many of the forms are possible direct projections of electrical impulses from the brain seen during states of altered consciousness . . . ‘Entopic’ images that manifest as points of light in the absolute darkness of the mind in the cave . . .

Keith Payne – from the Exhibition Catalogue

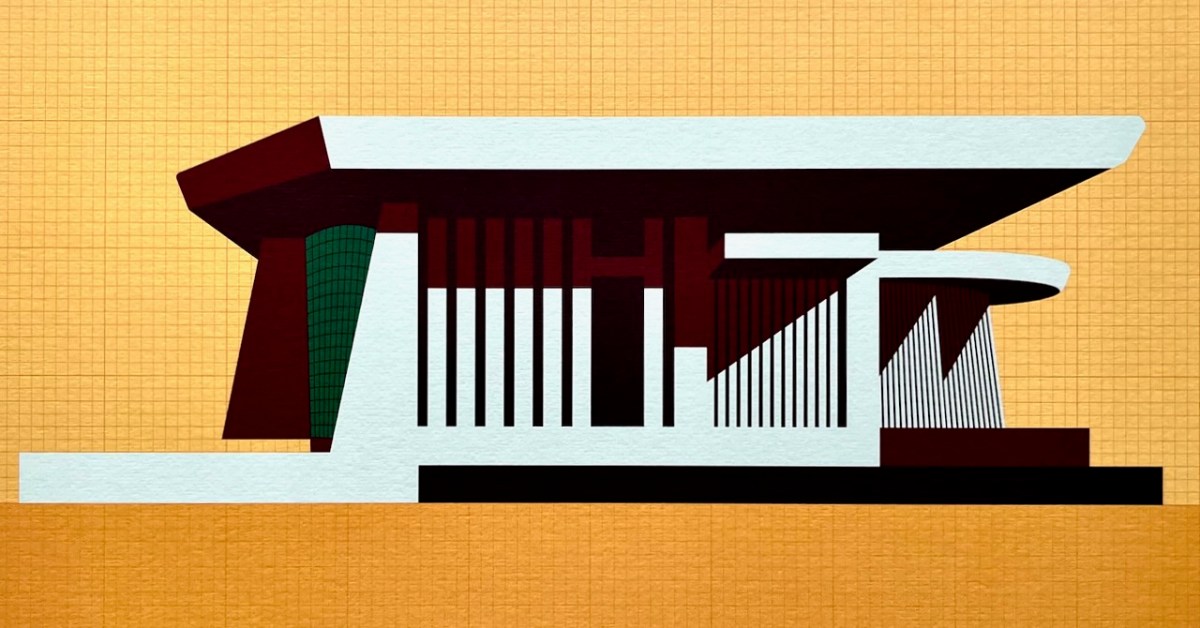

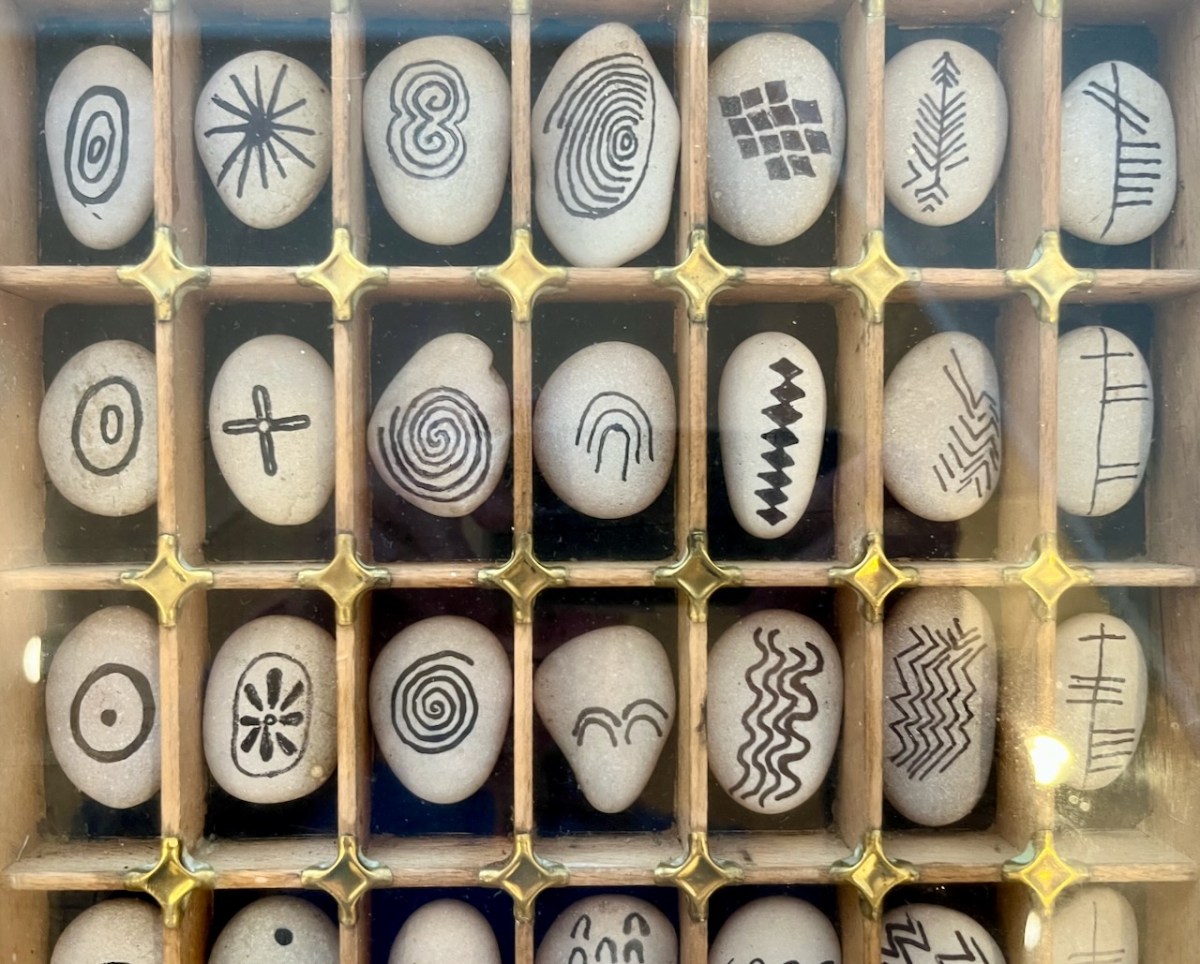

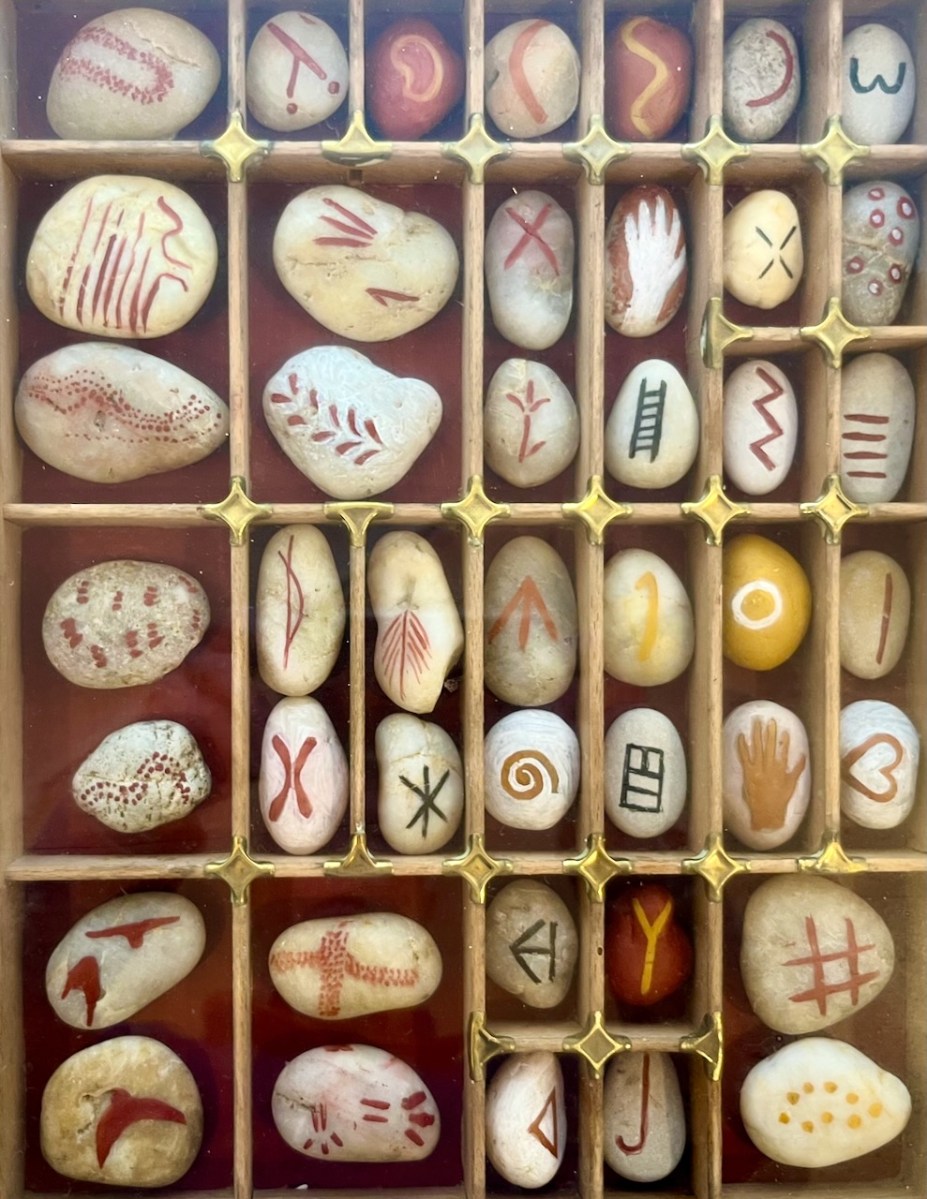

Font Tray – part of a larger work titled The prehistoric development of visual language:

. . . Reading from left to right are the earliest images from South African caves then through Palaeolithic, Neolithic, to a column of Ogham which reads from bottom to top: “Visual Language” . . .

Keith Payne – from the Exhibition catalogue

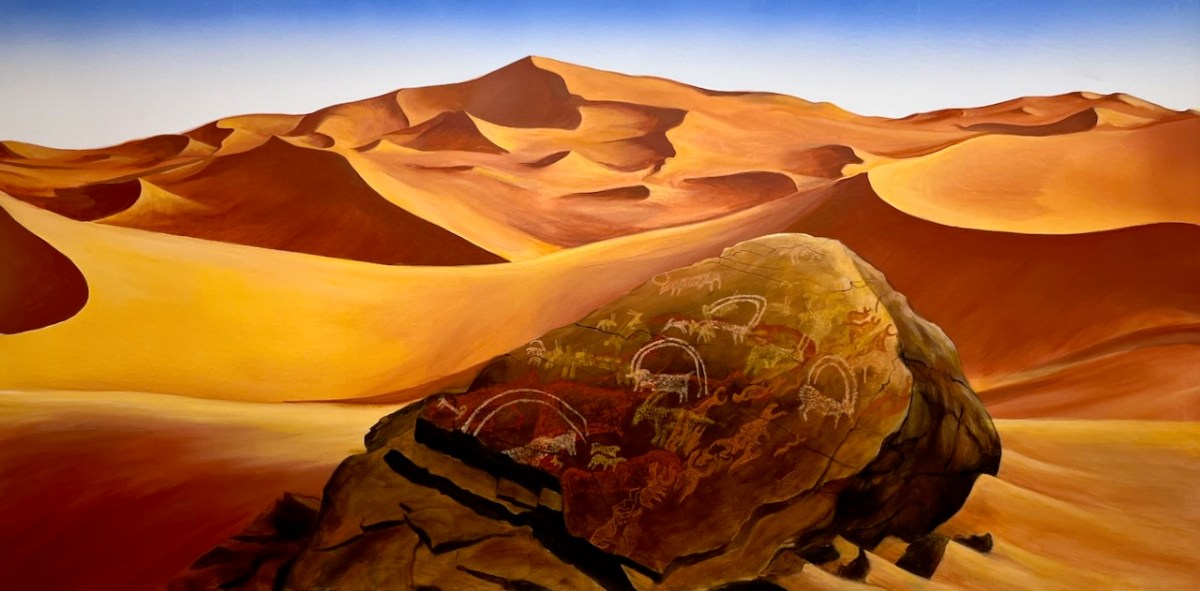

Empty Quarter (above) – a geographical region in the southern part of Saudi Arabia: the largest continuous sand desert in the world. Now scarcely populated it was in prehistory more temperate and the petroglyphs represent fauna of the time. Keith has painted the images in different colours to indicate the different periods of engraving.

Kakapel (and detail), Chelelemuk Hills, Uganda (above). Keith has travelled across the world to find his inspiration: in this painting – set at the entry point to the spirits living within the rock – are three styles: geometric images by the Twa people, pygmy hunter gatherers; these are overpainted with cattle by later Pastoralists.. The final abstract and geometrical designs were added by the ancestors of the Iteso people who migrated from Uganda.

Lokori (above) – site of the Namoratunga rock art cemetery in Turkana Country of Kenya. Located on a basalt lava outcrop adjacent to the Kerio River.

Left side above: Paleolithic Images – found in paleolithic sites worldwide: Believed to be visual statements perceived during trance states. Right side: Entopic Images – produced in the visual cortex. Often geometric in form and linked to the nervous system, seen as a visual hallucination. Noted during altered states produced by the use of the entheogens and trance states, fasting and the total deprivation of all light.

Schull Blue House Gallery: Keith Payne’s Namoratunga Rain Man petroglyph on the left.

Teana Te Waipounamu, New Zealand

From Signs + Palette of Ice Age Europe: a possible Visual Language.

Waiting Room:

. . . Approaching the mystery of the sacred space one dwells, initially, in the First Chamber. Many caves of the Mid region of France are very deep with passages, rivers and massive chambers which stretch for miles. To enter is to commit to a journey into the Sepulchre. The first chamber is for adjusting to experience ahead, perhaps initiation into the mystery of total light deprivation with the sound of beaten lithophones and flutes, echoing through the darkness. Or the revelation of your totem in a state of trance, to then be led deeper to meet with the serpent force of the mountain and shown the way of the Shaman . . .

Keith Payne – From the Exhibition Catalogue

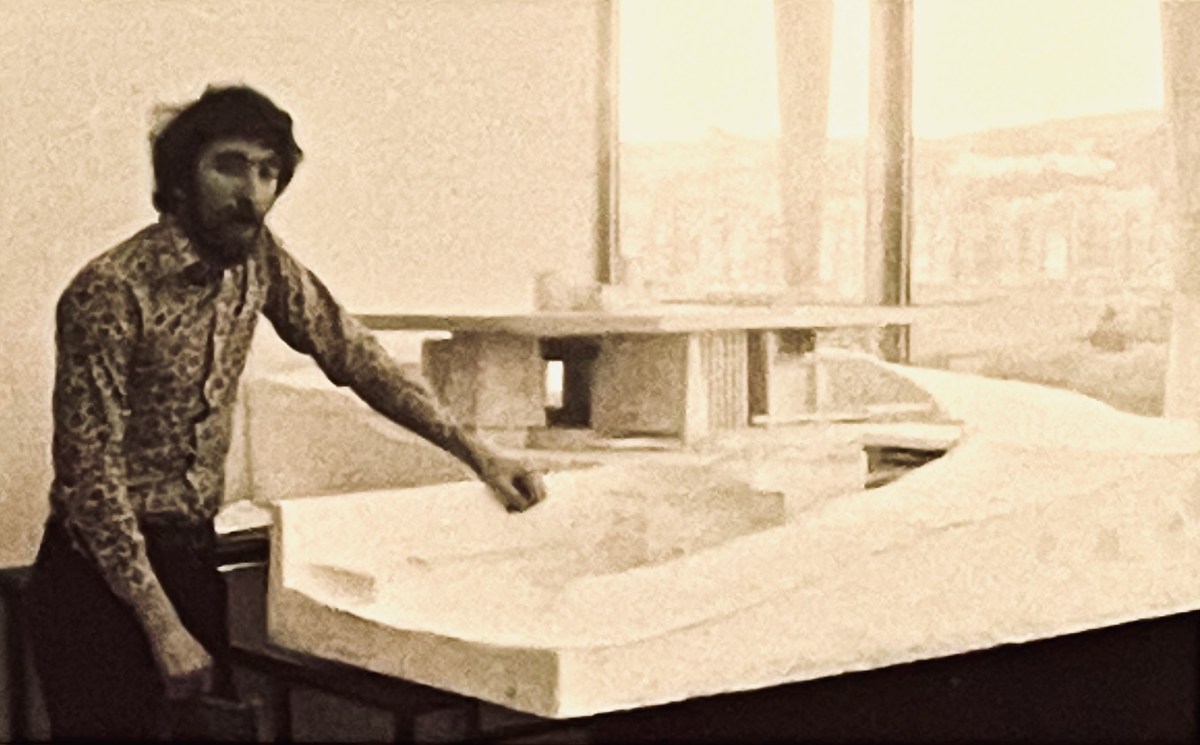

That’s me – at Keith’s Burren exhibition – awestruck by his Venus of Laussel.

Ronan Kelly discovered Keith Payne’s West Cork studio in this YouTube video