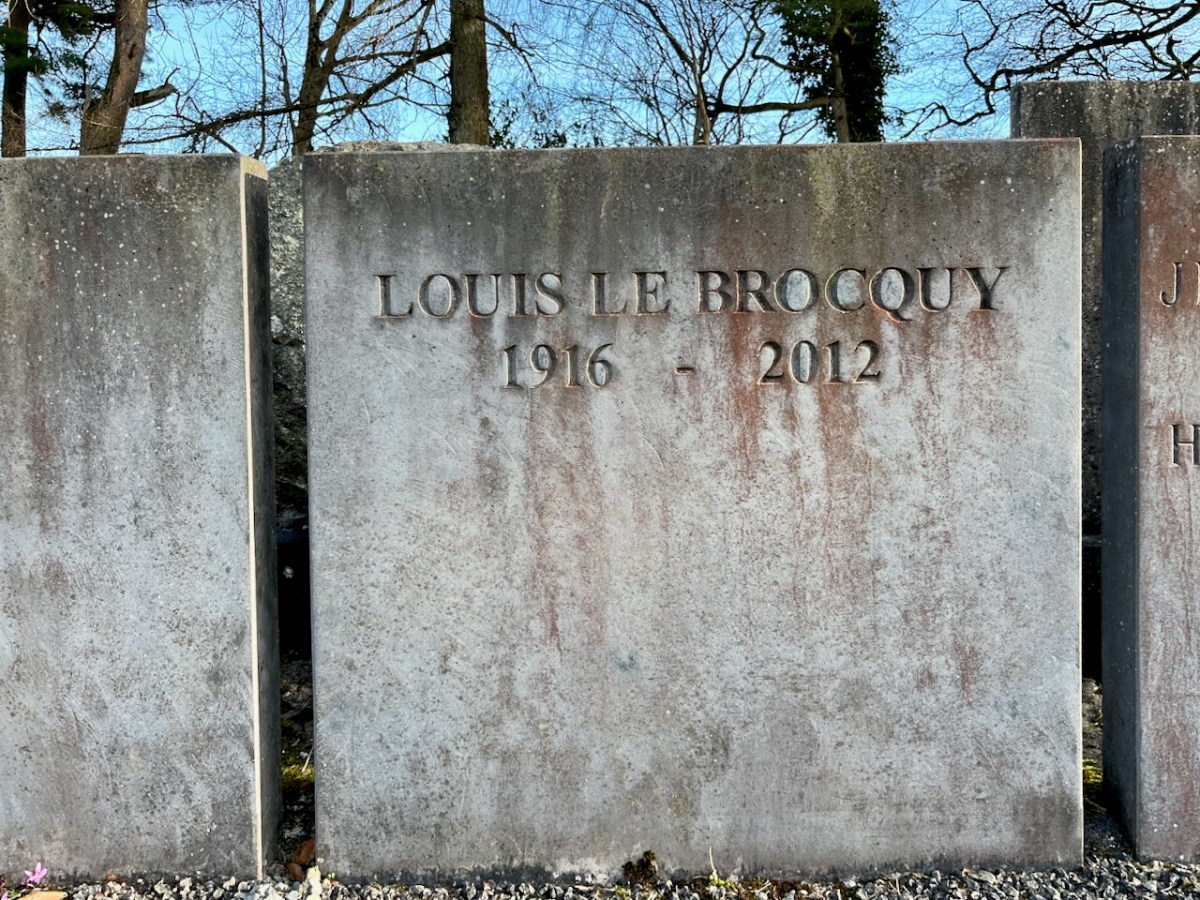

Adam and Eve in the Garden is an Aubusson tapestry, from the Atelier Tabard Frères et Soeurs (artist website) designed by Louis le Brocquy and dating from 1951-52. Le Brocquy was born in Dublin in 1916 and led a long life which included travelling extensively across continents, always completely engaged in art. He died in Dublin in 2012. On his death, President Michael D Higgins said: ”Today I lament the loss of a great artist and wonderful human being whose works are amongst this country’s most valuable cultural assets and are cherished by us all. Louis leaves to humanity a truly great legacy.” In 2002 the National Gallery of Ireland acquired le Brocquy’s painting ‘A Family’ – the first work by a living artist admitted to its permanent collection.

While out exploring the byways of rural County Wicklow, we chanced upon le Brocquy’s burial place. It’s in the little Church of Ireland graveyard at Calary. We had never heard of it before but – as we reconnoitred – the realisation dawned upon us that this is a very special site. Le Brocquy is probably the most eminent artist interred in these grounds, but he is only one of very many who have presumably chosen to spend eternity in this remote but extremely beautiful corner of rural Ireland. The views towards the not-too-far-away mountains are dramatic.

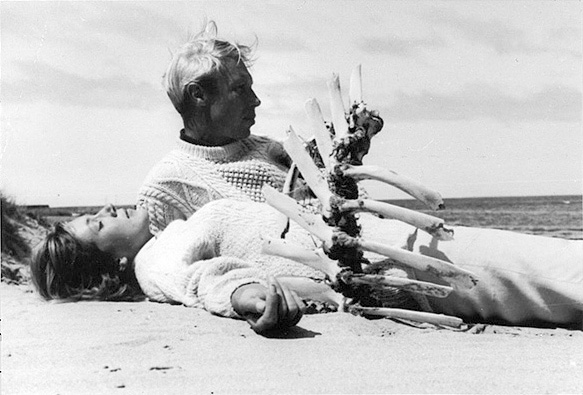

Le Brocquy’s wife, Anne Madden was born in London in 1932 to an Irish father and an Anglo-Chilean mother, and is still living. Madden spent her first years in Chile, where her Father owned a farm. Madden’s family moved to Corrofin, Ireland when she was ten years old. During the 1950s she met le Brocquy who was then working in London. They married in Chartres Cathedral in 1958 and set up house and studio in Carros in the south of France, where they remained until 2000. The empty plot at Calary beside Louis is presumably saved for her: she will add significantly to the artistic distinction of this community. The plot to the south of him is taken by Anne’s mother – Esther Madden Simpson – and brother – Jeremy Madden Simpson.

Anne Madden and Louis le Brocquy, 1974 (public domain). From that year onwards the family spent long summers on the Beara Peninsula.

A relatively recent gravestone added to Calary is this one, dating from 2018. It remembers Nicole Fischer, a viola player with the RTE Concert Orchestra and the Amici String Trio. Sadly, her death occurred when she was in the prime of her life.

This impressive and beautiful gravestone is the work of Wicklow sculptor Séighean Ó Draoi. There are a number of unusual markers within this site: every one tells a story, of course.

Maurice Carey led a distinguished life in the Church of Ireland. He served as Dean of Cork from 1971 to 1993, when he retired, and in retirement returned to his native Dublin where he was in charge of St John’s Church, Sandymount. While in Cork, Dean Carey presided over a period of great change in St Fin Barre’s Cathedral and he was instrumental in setting up the St Fin Barre’s Study Centre. He also achieved much in the musical and liturgical life of the cathedral. “. . . His freshness of mind contributed greatly to this success and he was kind and helpful to younger clergy at the start of their ministry . . .” (obituary).

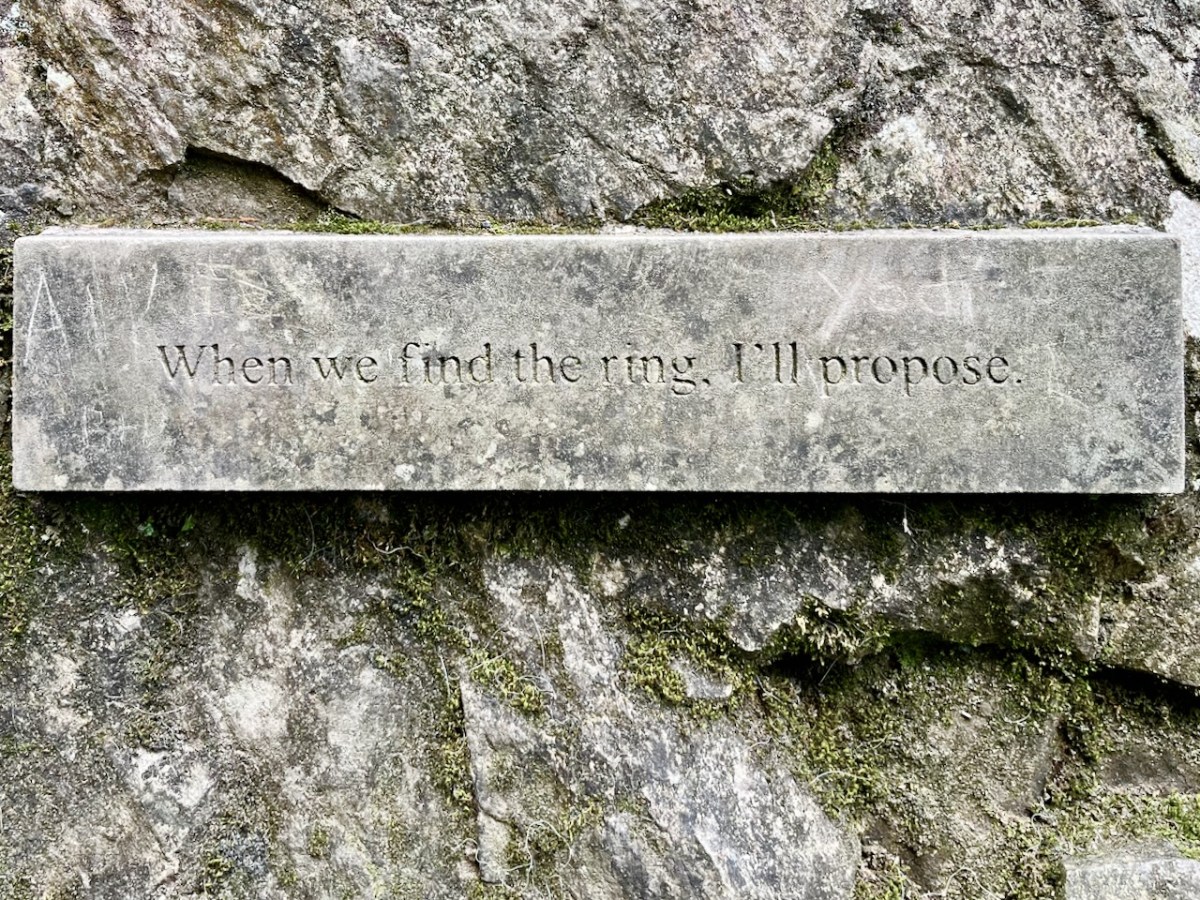

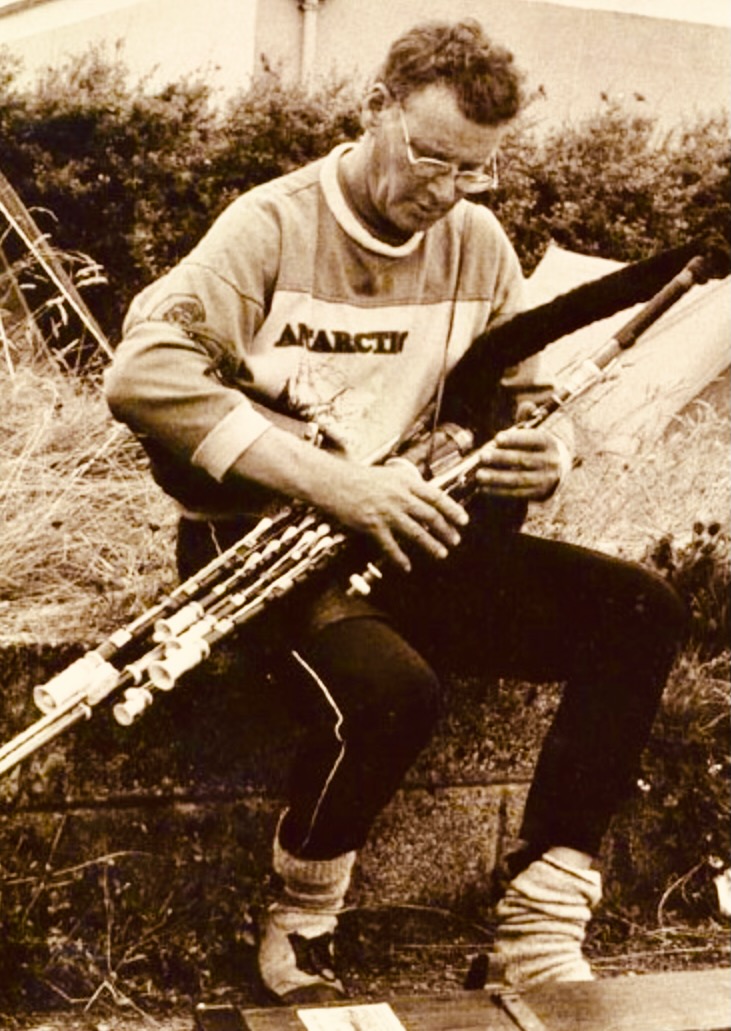

This stone belongs to Ronnie: Ronald James Wathen, who was born in 1934 and died before his time, in 1993. He was famed as a poet but also climbed mountains – and played the Uilleann pipes (https://www.discogs.com/artist/365089-Ronnie-Wathen):

The poet’s printed obituary sums up a notably eccentric life:

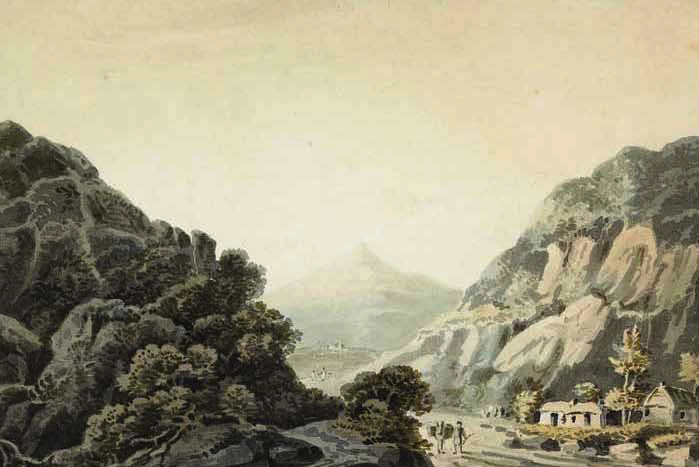

. . . I feel there may be a ‘most individual and bewildering ghost’ glaring with mock ferocity over my shoulder, a restless shade who would never forgive me if I tried to bury him with platitudes. Ronnie Wathen was quite spectacularly different: unpredictable, provocative, abrasive yet stimulating in argument, generous with himself, always able to see and articulate the quirky side of life. In Ireland Ronnie’s first poems appeared and many slim volumes were to follow. He had a most splendid, if unruly, facility with words. Usually he employed them seriously but he also loved frolicking with them, standing them on their heads just for fun. He wrote about anything and everything that caught his fancy, as a poet should . . . the last I saw of Ronnie was when he strode off up the road to do a kindness to an old friend. I must end with a grumble. Ronnie was an insomniac, never known to leave a party until very late. His parting prank was to quit the party of life far too early, at the age of 58, just to tease I like to think. It was a cruel jest . . . he held his final party at the little church of Calary, below Sugarloaf Mountain, in the verdant lap of his beloved Wicklow Hills. On that sunny autumn afternoon many, many friends crowded the church, farewells were spoken in prose and verse, laments welled up from three of the finest pipers in Ireland and a lone fiddler knelt by the open grave and hauntingly played the restless Ronnie to his rest . . .

Mike Banks

Conor Anthony Farrington was born in Dublin in June, 1928. His distinguished career included writing a number of plays for radio and theatre. Notable, certainly, were: Death of Don Juan (1951), The Tribunal (1959), The Good Shepherd (1961) and The Ghostly Garden (1964). ‘The Language of Drama’ in The Dubliner (July-August 1962) concludes the following: “…there are three reasons for a ‘radical alteration in the language of drama’ – viz, ‘the audience’s reason’, the ‘actor’s reason’, and ‘the dramatist’s reason’ – since ‘it is actually by means of particular words and phrases that he discovers his character’…” In later years appeared a collection of short stories (Cork: Fish Publishing 1996).

Another effectively simple slab remembers the sculptor Frank Morris, born in Arklow, Co Wicklow. He spent some years working with the Irish Forestry Department: while there he became a skilled wood-carver. The Dictionary of Irish Biography states that “. . . Carving for him was akin to peeling an onion to reveal the form within . . .” He also developed skills in sign-writing and letter-cutting. Have a look at his magnificent beaten copper door in the Holy Redeemer Church in Dundalk:

It’s interesting to find a Jewish grave in a rural Irish parish: Evelyn and Bruno Achilles (above and below).

In the 1930s The Schools Folklore Collection produced some memorable notes about the parish of Calary:

. . . Glasnamullen is our town land and there are nine families in it. Calary is the name of our parish. There are about twenty-six people in this townland. Sutton is the most common name in this district as their are four in Glasnamullen. All the houses in our town land is slated, but there are three or four thatched houses outside the townland. This place is called Glasnamullen as long as anyone can remember. Mr Arthur Sutton is seventy six, he lives in Glasnamullen, but Mr Fortune is one hundred and Mr Stokes is eighty six. They dont know any Irish, but they are great for telling stories in English. When my father was small he used to get Mr Stokes to tell him stories. Mr Fleming told me a story about Mr Byrne, The Paddock, Kilpedder. Once upon a time a man was cutting down a hawthorn tree in an old fort and as soon as he did a wind rose and took it away and over his head were thousands of birds. No one ever knew where the hawthorn went to, but everyone said that the fairies must have done it. They never plough the land owing to that. St Kevin is said to have blessed a little well beside a river in Ballinstowe. Every one goes and drinks it when they have colds. It is also said it has the power to cure sore eyes. There are pieces of cloth on the bushes around it left by people whose eyes were cured . . .

Muriel Taylor, aged 14

Schools Folklore Collection

“Beware of the Witches you meet in the ditches, between Calary bog and Ballinastowe.” – a local saying!

The ‘fishy’ gates to the graveyard are also artistically wrought.

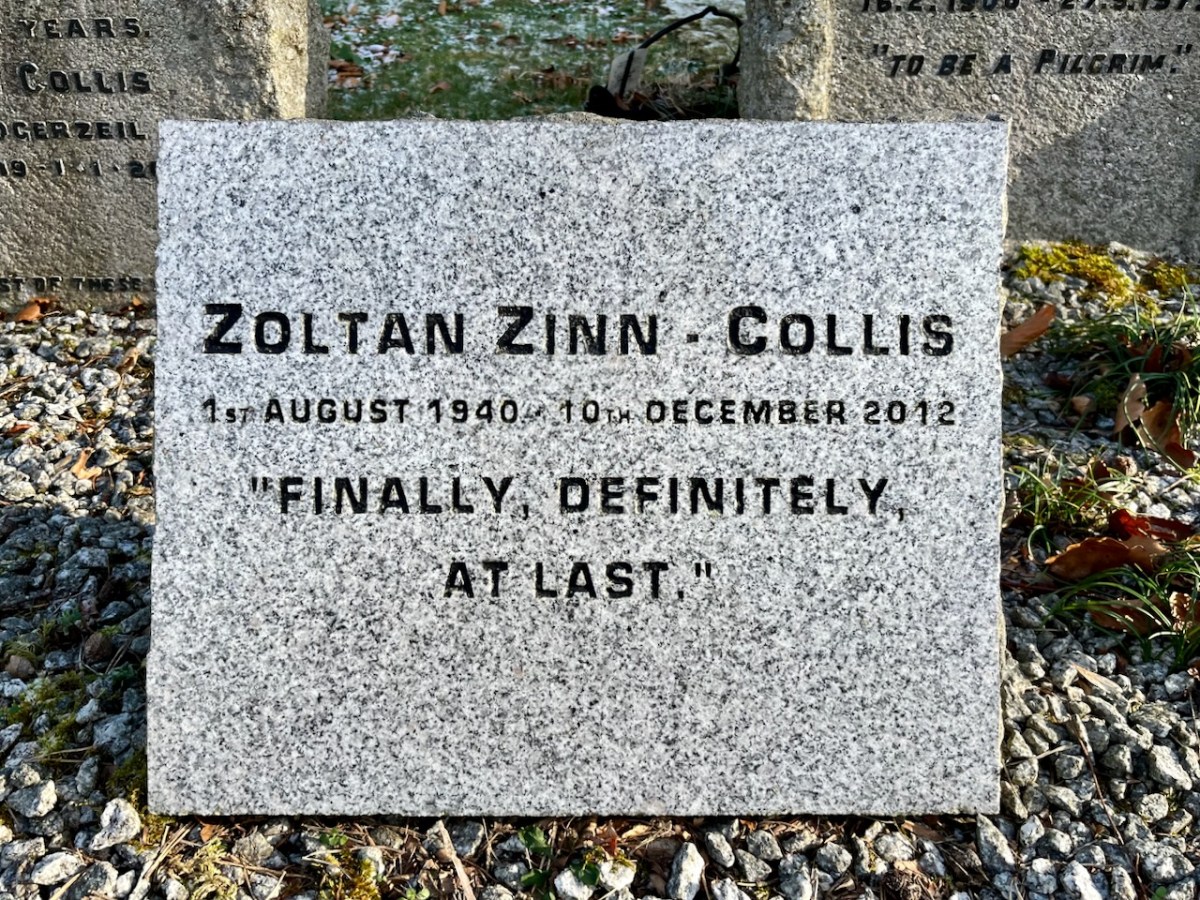

Zoltan Zinn-Collis was a holocaust survivor. Many thanks to our friend Paul Smith for sending us this information.

I have concluded that this fairly recent grave (2011) is in memory of a mariner. You can see that the inscription is within a porthole – and there is an illustration of a sailing boat. After much searching, I came across a funeral notice – here is a brief summary:

. . . HANNA Simon (late of Bray, Co Wicklow, formerly of New Zealand) – September 7, 2011, suddenly, son of Meg and the late Pat Hanna and brother of Tim, Mike, Pete, Kristin and Jane; sadly missed by his partner Sonja (McEnroe), her daughter Tali and her partner Danny, his sons Rowan, Aiden, Kieran and their mother Ann, his mother, brothers and sisters, extended family and many friends. Reposing in the factory workshop, Mill Lane, Bray from 4pm to 9pm tomorrow (Sunday). Removal on Monday to Calary Parish Church arriving for a Funeral Service at 2.00 o’clock followed by interment in the adjoining churchyard . . .

Funeral Notice

This is not an exhaustive account of the graves in Calary: it’s a selection only. Hopefully it’s sufficient to send you in this direction if you find yourself over in the east. It’s a beautifully atmospheric place. Let’s finish where we started – with a Louis le Brocquy tapestry. This is: Garlanded Goat 1949-50, Aubusson tapestry, Atelier Tabard Frères et Soeurs (artist website).