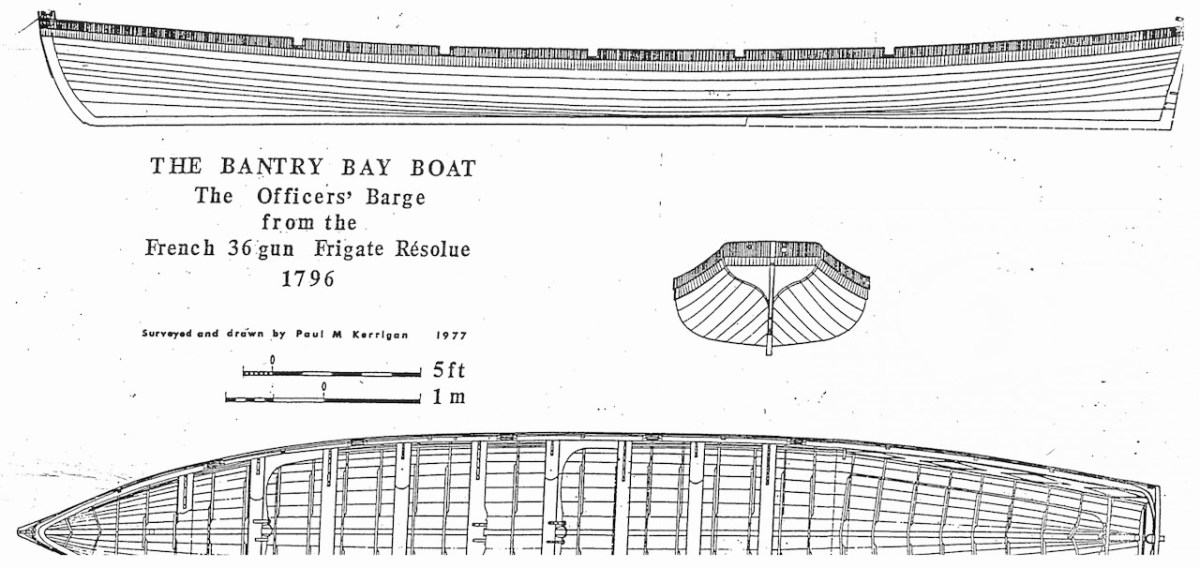

In last week’s post I described a unique type of boat that was connected with Bantry, here in West Cork. Today we are also focussed on Bantry, but this time on architecture: the Public Library, which is one of the most unusual and innovative buildings from twentieth century Ireland.

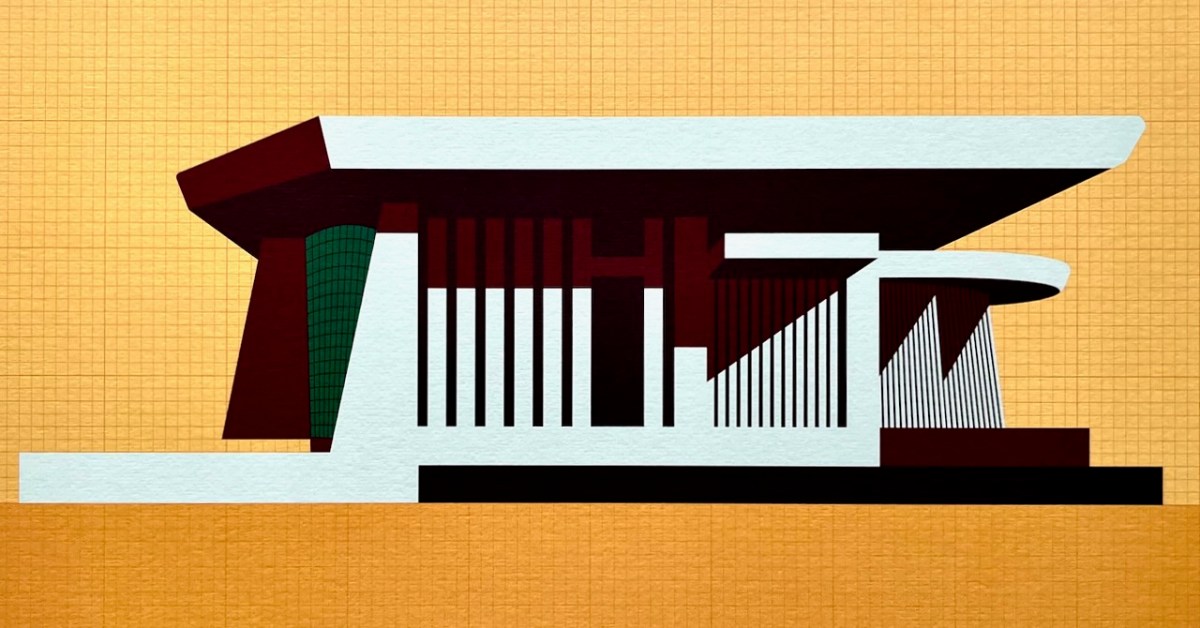

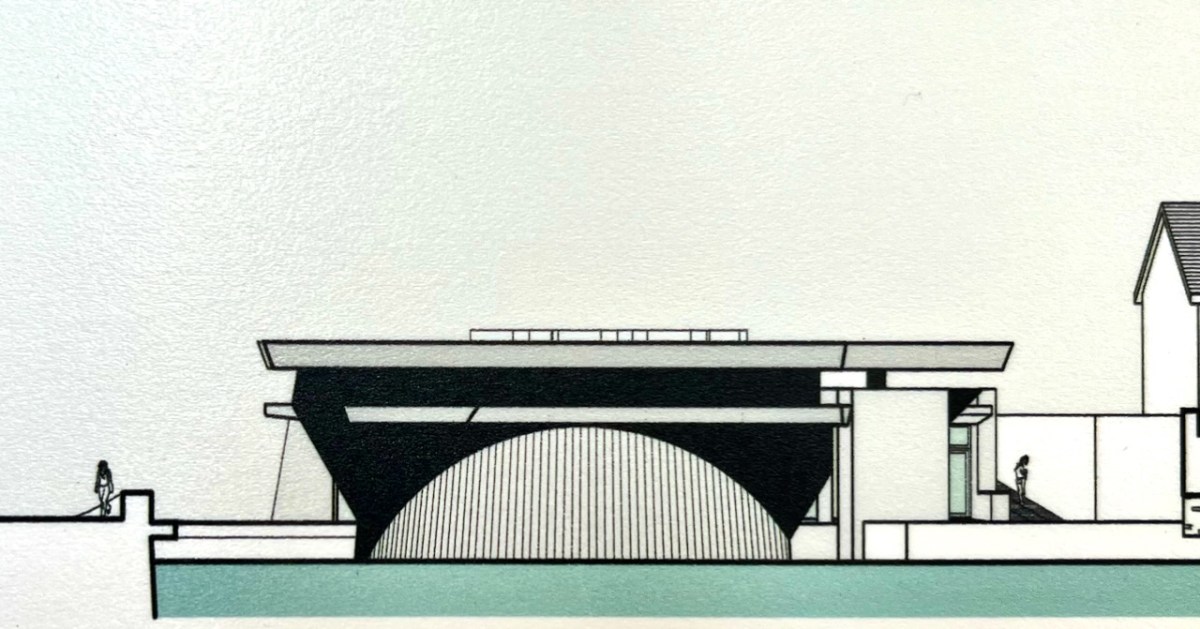

Here is the building as we see it today. The header is a limited edition print, a collaboration between Dermot Harrington of Cook Architects and Robin Foley of Hurrah Hurrah celebrating the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the completion of Bantry Library in 1974. For me, the print captures perfectly the iconic graphic of this most unorthodox design.

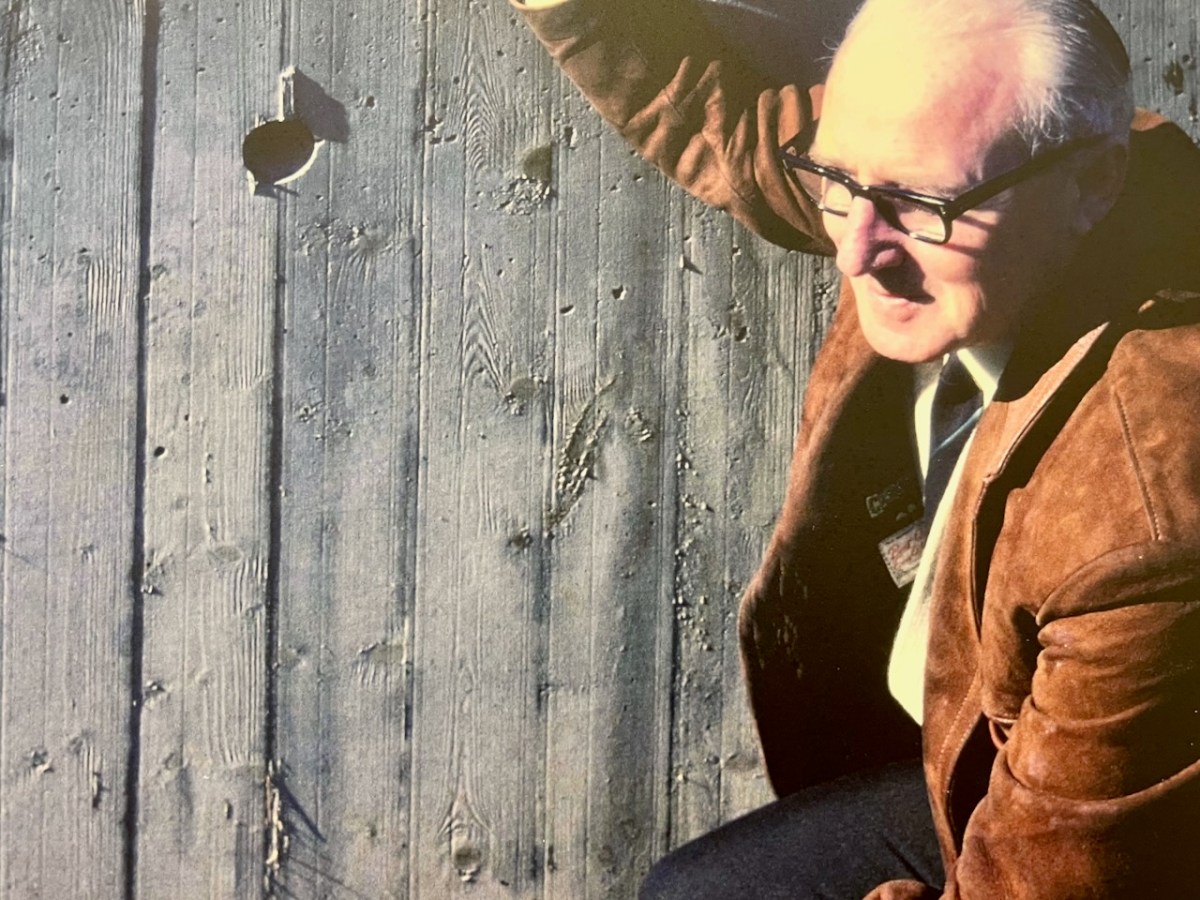

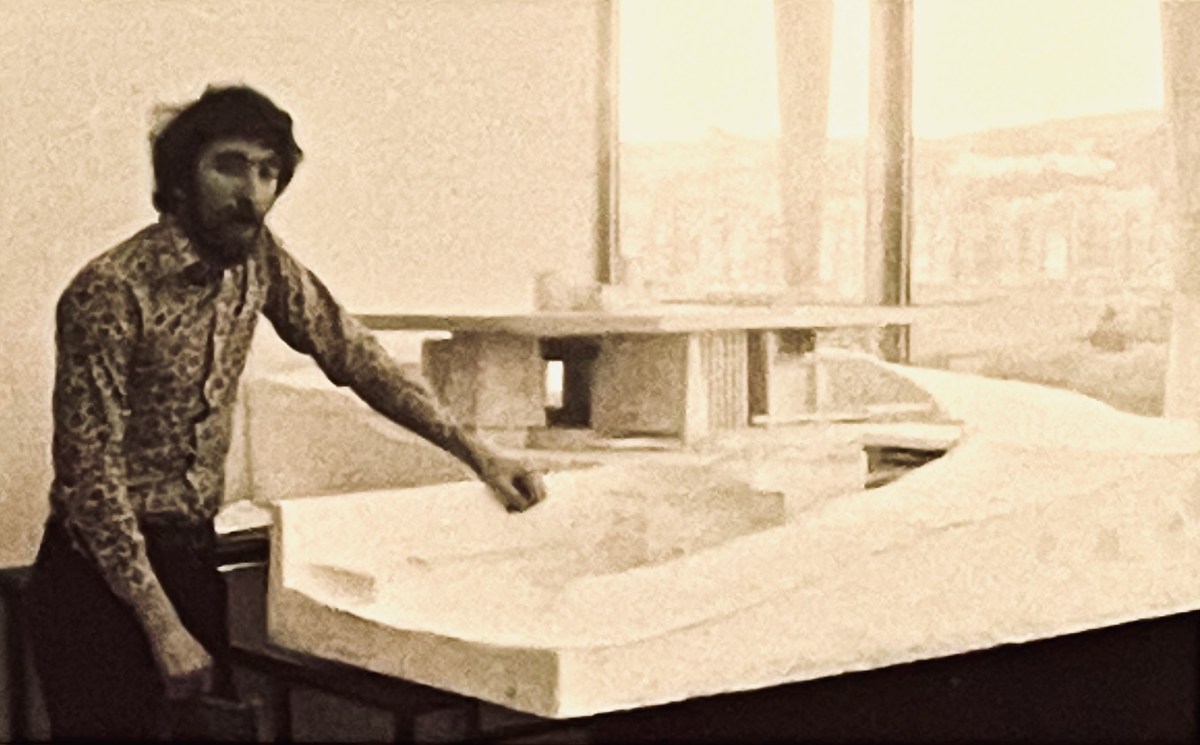

The Library was conceived by Patrick McSweeney (above) – Cork County Architect between 1953 and 1975. He deserves a post of his own one day, as he was responsible for some outstanding buildings in the county. Two of his assistants in the Architect’s Department at the time were Brian Lalor and John Verling. Both had a hand in the genesis of the Library. Interestingly for us, McSweeney, Lalor and Verling were all living around Ballydehob in those days – it was a swinging village!

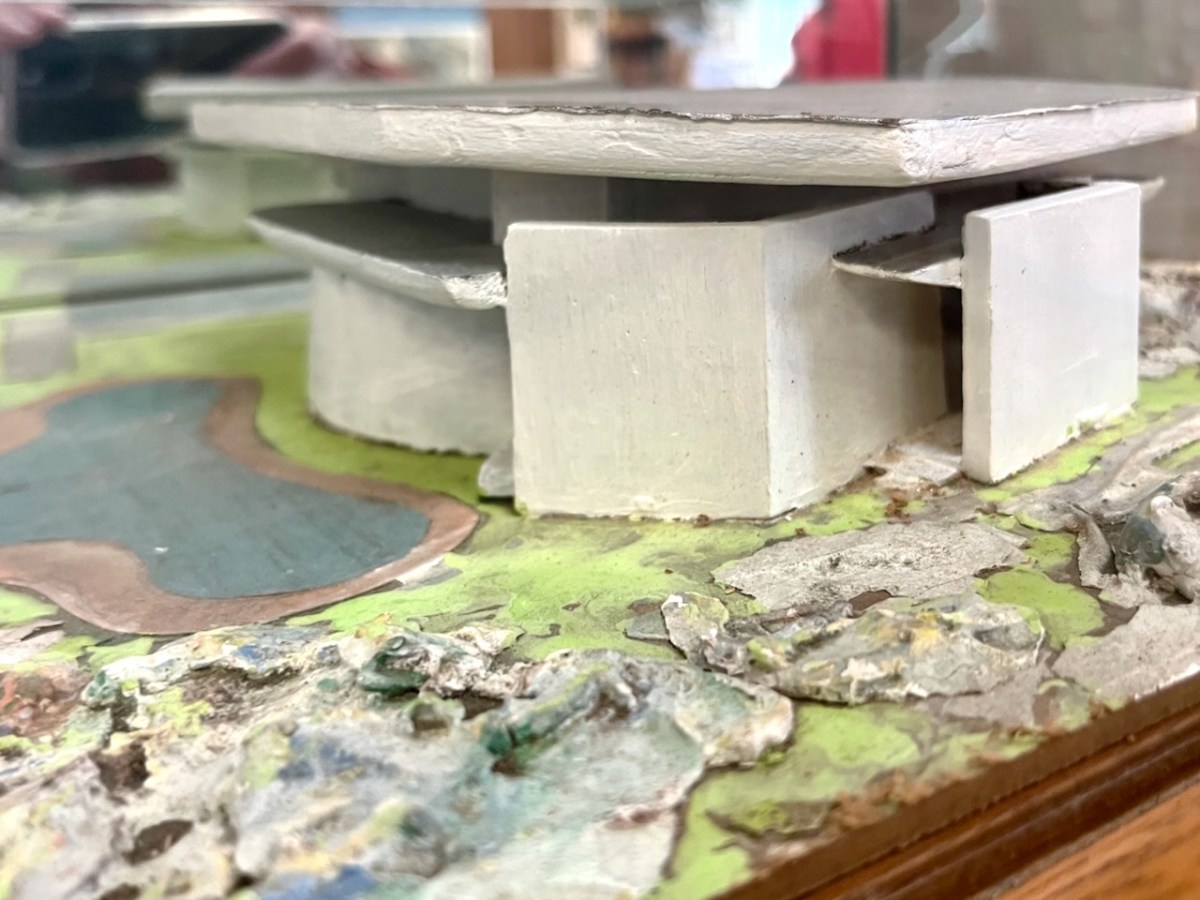

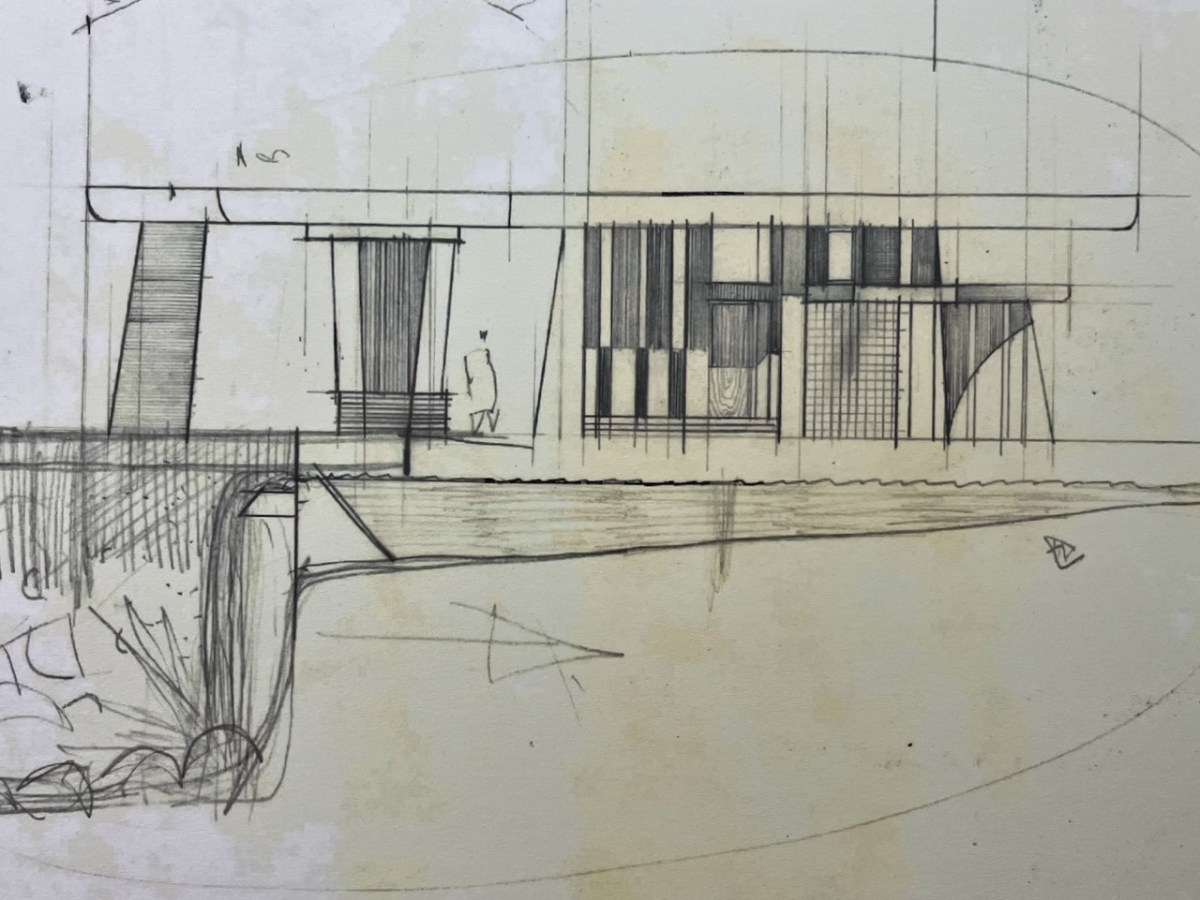

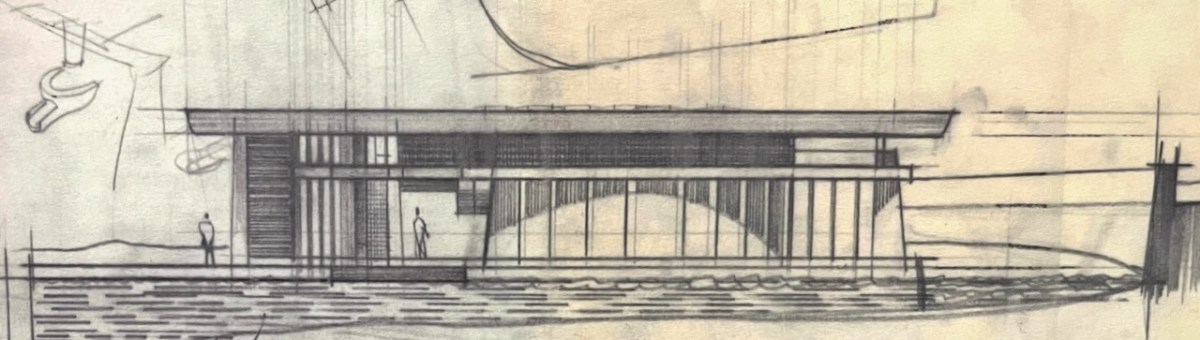

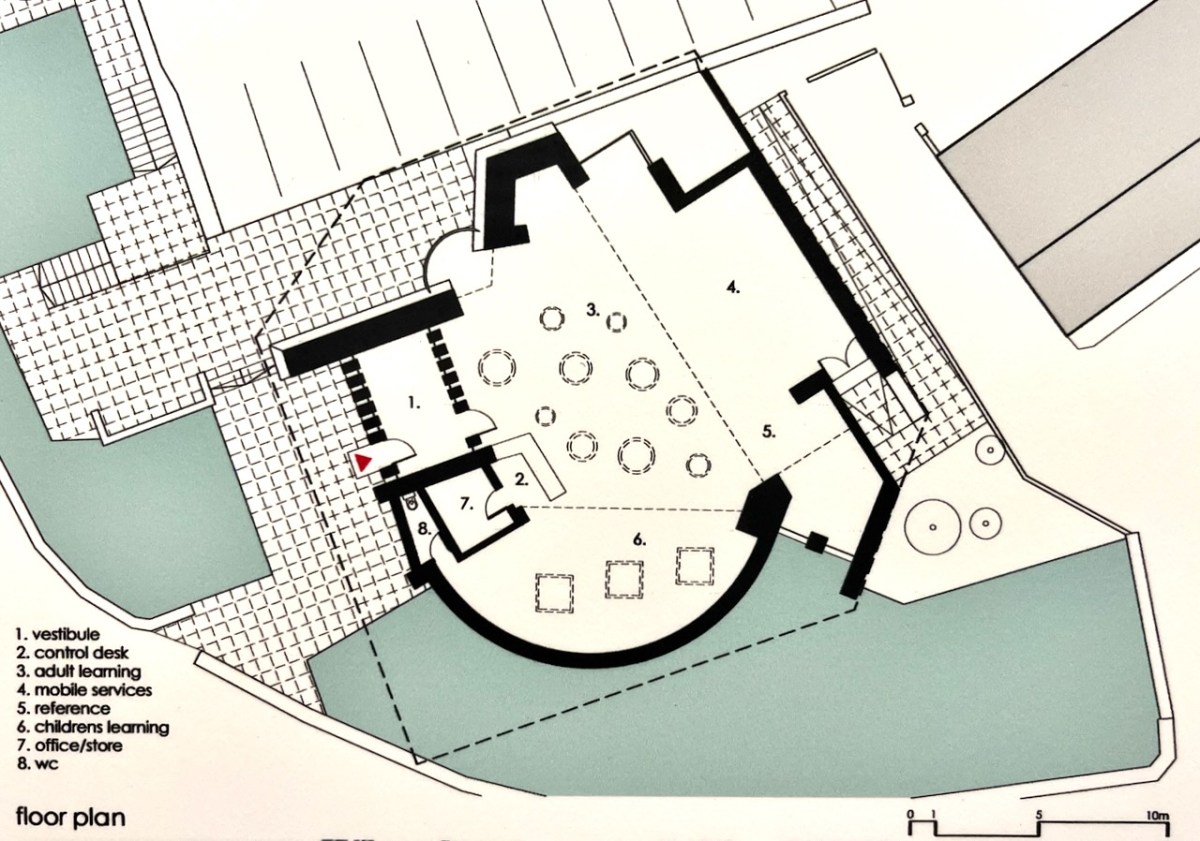

In the era before computers were universal in architects’ offices, everything was drawn by hand – or modelled. Brian recalls that Pat (McSweeney) called him into the office one day, handed him cardboard, tape and scissors, and instructed him to make a model of a building shaped like a Bronze Age dolmen. And he wanted it made in a hurry! It could well have been the one shown above – which still exists. Remarkably, although this model was made in the early 1960s, the building that resulted in the 1970s was very similar in form. Later, John Verling produced a balsa-wood model upon which the design production drawings were based:

That’s John Verling, above, with his model. He and his wife, Noelle, are the subjects of the current exhibition in the Ballydehob Arts Museum (click the link). Following are some of the design sketches carried out by Harry Wallace who was leading the team in County Hall, and detailed drawings of the building that eventually ensued.

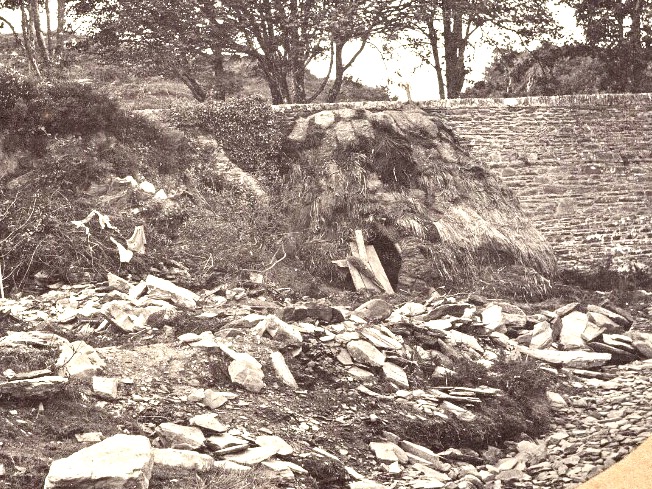

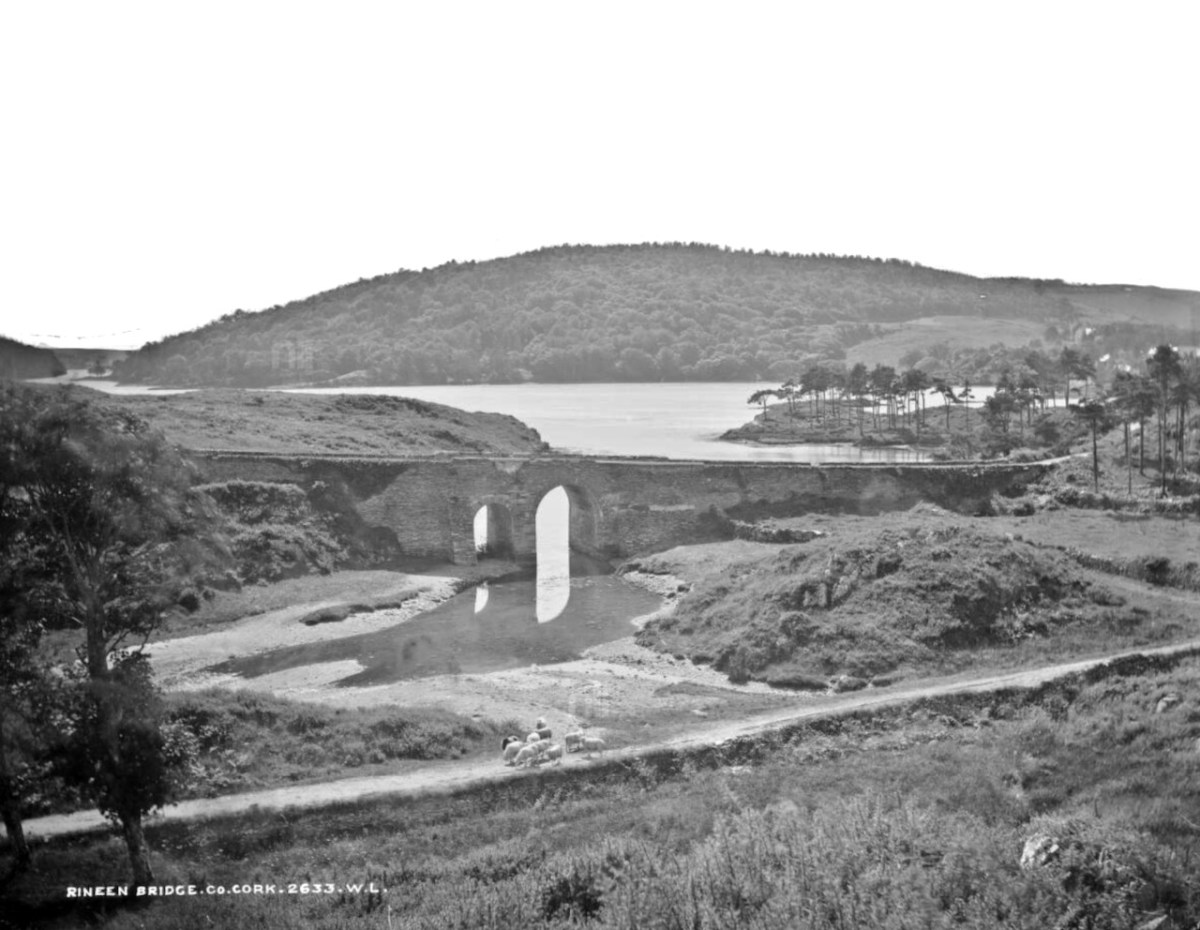

Let’s look a bit further at the early concept work, especially that first model. It’s said that McSweeney was inspired by a ‘Dolmen’. In fact we would today call that type of early megalithic structure a ‘Wedge Tomb’ or a ‘Portal Tomb’. At its simplest, this is a large flat stone slab (or slabs) supported on vertical stone slabs: it was probably a burial chamber, perhaps with its opening facing the sunset at a particular solar event. The closest such tomb structure to Ballydehob is the one featured in Finola’s post today. I wonder if Pat McSweeney was aware of this local one? He would have certainly been aware of the striking example at Altar, further west on the Mizen Pensinsula.

Another view of that very early model demonstrates how the roof shape echoes the lines of a portal tomb slab: look at this further example from the Mizen, at Arderawinny:

Returning to the twentieth century, and the Bantry Library project, construction posed many problems, using techniques which might have been considered at the leading edge of architecture in its time and place. Across the sea similar experiments were taking place. I was at the centre of them! I completed my architectural education in the late 1960s and went to work for the Greater London Council. I saw going up around me on the South Bank of the Thames a development which included the Hayward Gallery (below): its design (described as ‘brutalist’), earned it the nomination of the ugliest building in Britain when it opened!

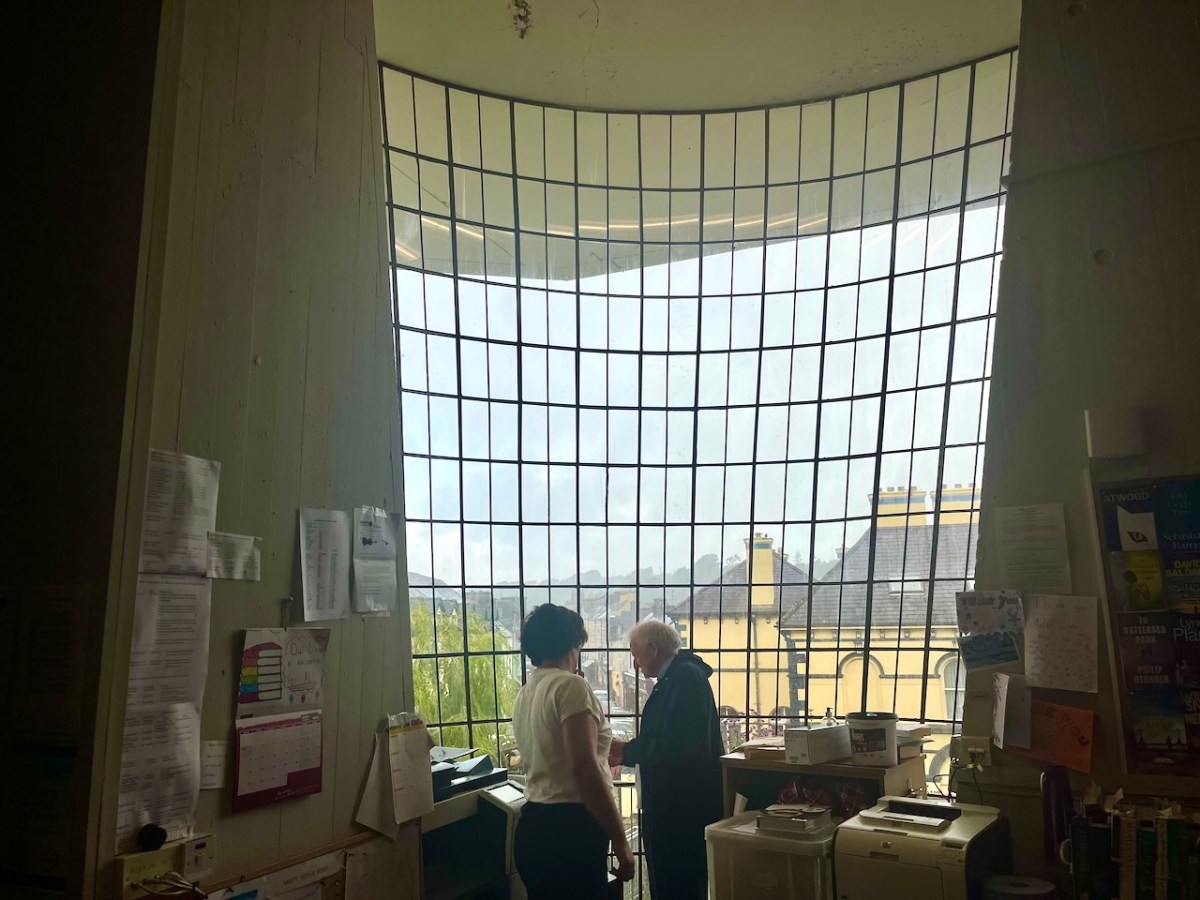

Larger in scale, this complex exhibits some of the features we see in Bantry: shutter-marked mass concrete, frameless glazing, bold overhanging roof planes… The Library roof cantilevers six metres in one part of the building.

The status of this building as an unique example of modernist architecture in Ireland has recently been recognised with a Heritage Council grant of over €250,000 to carry out refurbishments to some of the major elements.

. . . As Bantry Library approaches its 50th anniversary, we are committed to safeguarding this important building. As a protected structure within an Architectural Conservation Area, Cork County Council recognizes its responsibility to preserve and protect Bantry Library for future generations. The conservation works will take place during 2023, and we look forward to seeing the library restored to its former glory . . .

Tim Lucey, Chief Executive, Cork County Council

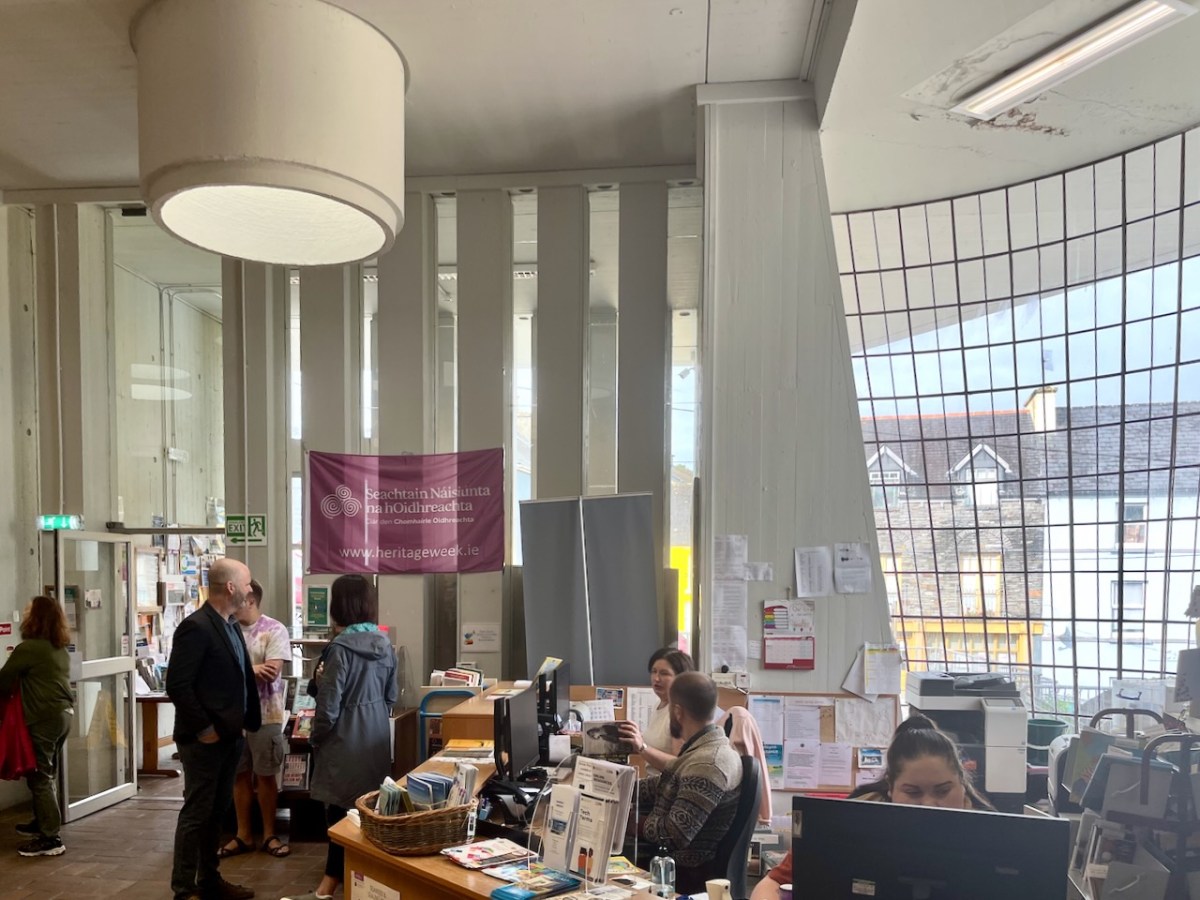

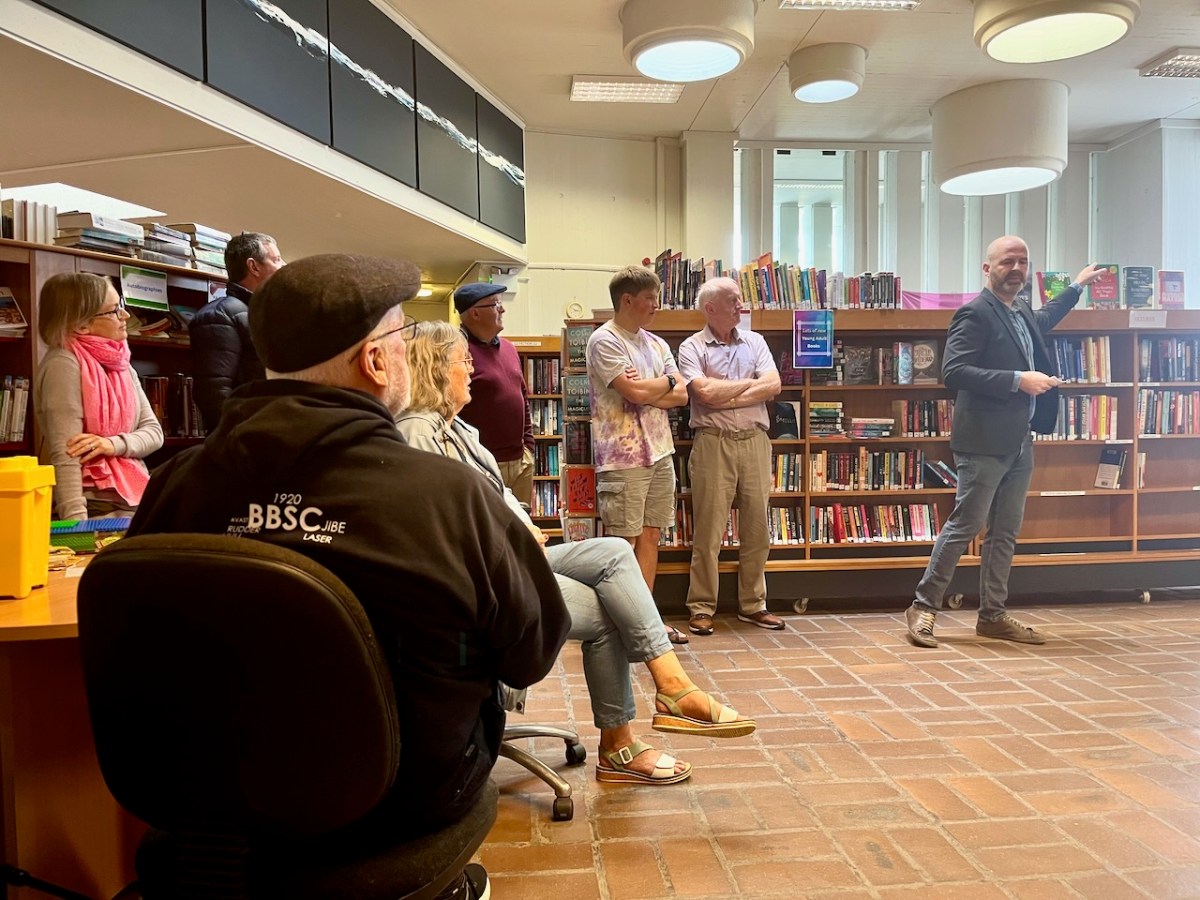

A Heritage Week talk was given by Dermot Harrington of Cook Architects at the Library (below). It was a most informative review of the building and its history.

Most of the original features of the building have survived in reasonable order. I was impressed with the ‘pipe lights’ which draw daylight down into the centre of the main room:

We also learned about the complexity of the building construction, and saw photographs of the steel reinforcement and board shuttering from fifty years ago:

Dermot Harrington pointed out that the building was effectively put together by only five men, under foreman Gerry O’Sullivan, who was just 27 years old. Neither he or any of the other crew had ever tackled anything like this before!

The Library is central to the life of the town, and still serves its original purpose. It’s eye-catching (perhaps sensational is a good word?) and very much alive and relevant. We look forward to the completion of the current works, and suitable festivities to mark the fiftieth birthday of this creative West Cork project.

Thank you to the Library for the information they provided and the display boards that are currently on show. Many of my illustrations are taken from these resources