I was around in London in the early sixties, and was definitely part of the swinging Flower Power scene: beatniks, Beatlemania, Carnaby Street, flowery shirts and ties (I’ve still got some of them – below – stashed away in my wardrobe!) – the regulation Afghan coat (and its distinctive smell) . . . What I miss most, perhaps, is the purple velvet flared trousers: sadly an expanding waistline quickly did away with them.

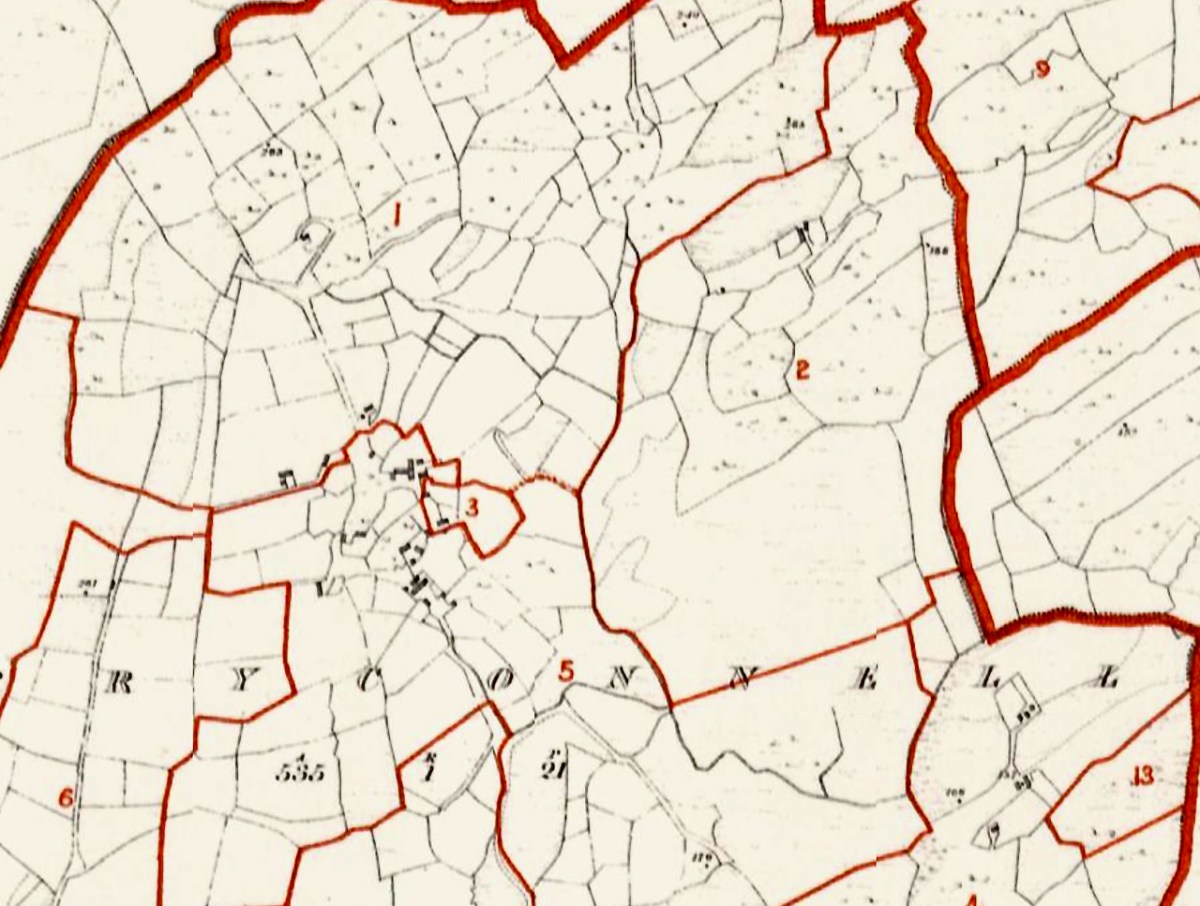

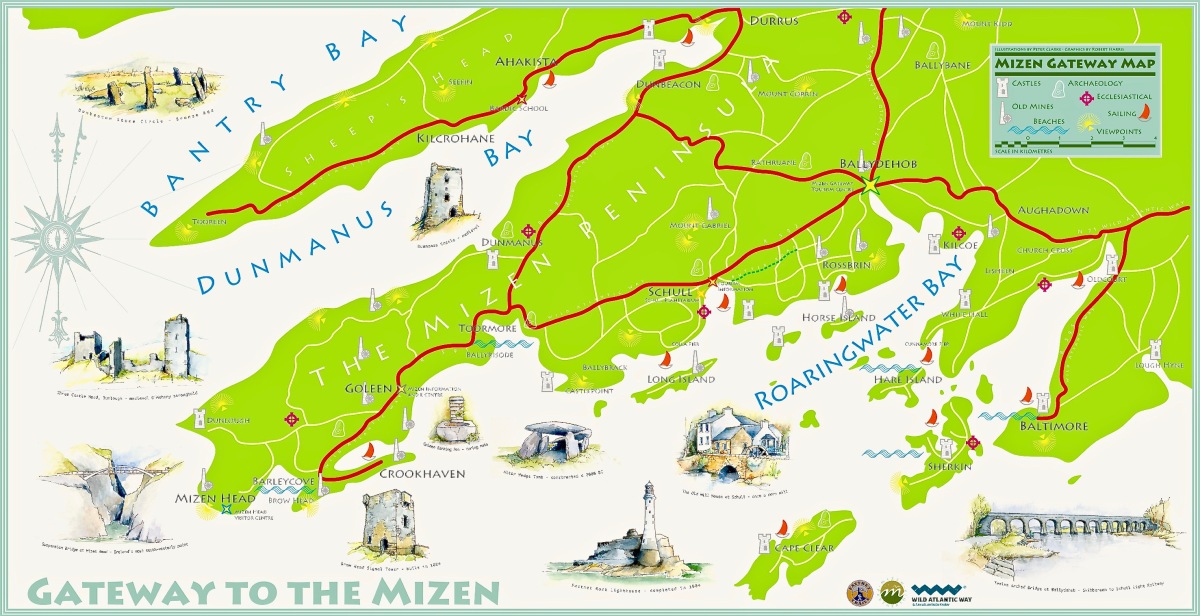

What is less well-known – in my generation at least – is the fact that there was a similar cultural phenomenon in one part of Ireland – our own West Cork! And it was centred on Ballydehob – that’s the main street, above. It’s a colourful village today – as it was then: well-suited to the cultural heritage which the artist community of the time imposed upon it. This building on the main street in those early days was particularly significant:

One of the artists who happened upon Ballydehob at that time lived on here to tell the tale (he still lives in the village and is still a working artist):

BREAKING NEWS: BALLYDEHOB IS DISCOVERED!

. . . During the early 1960s, a group of students at the Crawford School of Art in Cork, heard a rumour that something bizarre was happening in a village called Ballydehob. Here some vestige of Swinging London had taken up residence in a painted-up building called ‘The Flower House’. I was one of those students. We decided to investigate.

Since nobody owned a car, a parental vehicle must be ‘borrowed’. Somebody’s parent was away so this could be done without controversy. One of the know-it-all students announced that Ballydehob was in County Sligo and we would need money for petrol and have to camp when we got there. Nobody owned a tent. A forever-complaining student said that ‘He didn’t want to end up arrested as a vagrant and to have to sleep in a Garda station’. A few days later we left the Crawford en-route to County Sligo. Fortunately, a more astute student rummaged in the car as we were leaving the city for the West, found a road atlas and announced that Ballydehob was actually in County Cork, a mere two hours drive over the potholes. Tent-less or Garda station camping would not be required.

We arrived, we saw, we were astonished. Cork was then a darkly conservative place, ditto the Crawford and its staff members. What we found in Ballydehob was a house on the main street of the village with enormous flowers painted on the façade. It might have been in Chelsea or San Francisco. We entered to find a hive of creativity and alternative lifestyles. This was the world of women in flowing batik dresses, bearded men with bead necklaces and leather-thonged trousers. Even a cod-piece was observed. We sat in the café and drank coffee from the brownest of chipped brown ceramic mugs, ate inedible brownies and marvelled at the range of art and crafts being produced by this creative group.

This establishment, which seemed to have landed from another planet since the remainder of Main Street appeared to have experienced no visual or economic change from the images recorded in the black + white photographs of the 1900s, was run by two women, one German, the other English: Christa Reichel and Nora Golden. Here was a living example of William Morris’s dictum, ‘Have nothing in your homes that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful’.

Some ten years later, John and Noelle Verling (participants in that epic car journey) set up the Fergus Pottery in Dripsey outside Cork, later transferring it to Christa Reichel’s former premises in Gurteenakilla, Ballydehob, where it became a fixture of the creative community. A few years following, another member of the car-team, myself and Clair, came to stay with the Verlings, and also remained in the area, setting up an etching studio on the other side of Ballydehob.

Many of those who established the creative community of West Cork have died. Another generation has grown to maturity, further expanding the tradition of West Cork as a major and continuing centre of creative engagement in all of the arts, an epi-centre of delight. . .

BRIAN LALOR

That’s Brian, in his studio today. Just a few years ago – in 2018 – he and I decided that that creative time in the village needed to be properly celebrated, and we gathered around us like-minded enthusiasts, and opened up the Ballydehob Arts Museum, using a room kindly donated by those who had taken over the disused bank building, right in the centre of town:

That’s the inside of the Museum above: its first exhibition opened in the summer of 2018. We had another the following year, then Covid stopped us until last year, when we featured Ian + Lynn Wright. This year’s exhibition also features a ‘couple’ of working artists: The Verlings – Noelle + John.

John Verling was a contemporary of Brian Lalor (who has written the account above), and they both studied architecture and art in London and at the Crawford in Cork. Brian has penned for us his memories of sharing a studio in London with John Verling:

THE PERILS OF A SHARED STUDIO, LONDON, 1967

. . . During the late 1960s, John Verling and I, then students of architecture in London, shared a quite substantial studio in one of the leafier areas of Kensington. The building, a large brightly lit interior behind a row of decaying Victorian villas (it might originally have been a Victorian studio, we never discovered) had many more recent uses and the first task on gaining possession was to somehow manage to get rid of what had been left behind by earlier tenants; office furniture, old matresses, much unidentifiable plumbing apparatus and a stuffed fox whose pelt had been consumed by moths, were among the challenging contents.

Conversation among acquaintances in our local, the Norland Arms, evoked interest from other drinkers, an English sculptor and a South African photographer who asked could they share the space and, very willingly offered a down payment on the rent. This was agreed and not long afterwards the studio became operational, with both John and myself busy creating in our new-found haven, with only the occasional appearance of our fellow tenants. John was at that point concentrating on elegant photomontages as well as complex drawings of Portobello costermongers and was extremely productive, while I was engaged in a substantial series of elaborate and brightly coloured timber constructions enhanced by scaffold clamps, in a latter-day Bauhaus manner. Time passed, various local artists called to view the work and admire the space. We were exhibiting successfully and the studio became in W H Auden’s phrase, ‘the cave of making’. Our fellow studio members failed to turn up and when occasionally encountered in the Norland, expressed embarrassment in being behind with the rent while offering a contribution to ‘keep their name in the pot’. This was an extremely satisfactory situation with individuals happy to subsidise the rent but too busy to actually attend the studio.

A chance encounter in the Norland brought another hopeful artist to our acquaintance, David O’Doherty, Dublin painter, he worked at the international telephone exchange. He came, he admired the studio, and invited himself to join. Fatally, we agreed. An accomplished portrait painter, he often had a sitter posed, but seemed happy to work on, undisturbed by the other occupants. Our new tenant was affable, expansive, a storyteller. He became a permanent fixture. Suddenly we realised that we were entertaining a cuckoo in our midst. O’Doherty had moved in permanently, camp bed, small stove on which there was always a fry-up in progress, an endless stream of visitors, large canvasses propped against the wall, and the catastrophic revelation of his other occupation; he was a keen traditional musician, devoted to the Uillinn pipes. Suddenly the space, ample for John and myself to pursue our work, had begun to feel like a home for the demented.

Gradually it became apparent that our studio, which a year before had been, in the midst of the city’s turmoil, as quiet and remote as a stylite’s pillar, had metamorphosed into Picadilly Circus with noise, air pollution and crowd control issues. The dream of having a secure place in which to create had floundered on the fatal choice of an individual whose concept of an ideal workplace was perilously close to Francis Bacon’s taste for irredeemable chaos. I bailed out, John lasted a little longer. And the completed series of brightly coloured scaffold-clamp constructions, what of them? Occasionally I received reports of their travels. Before he emigrated to Boston, O’Doherty sold them to a construction company and they were later spotted decorating the foyer of a social welfare office in Amsterdam. After that only blessed silence . . .

BRIAN LALOR

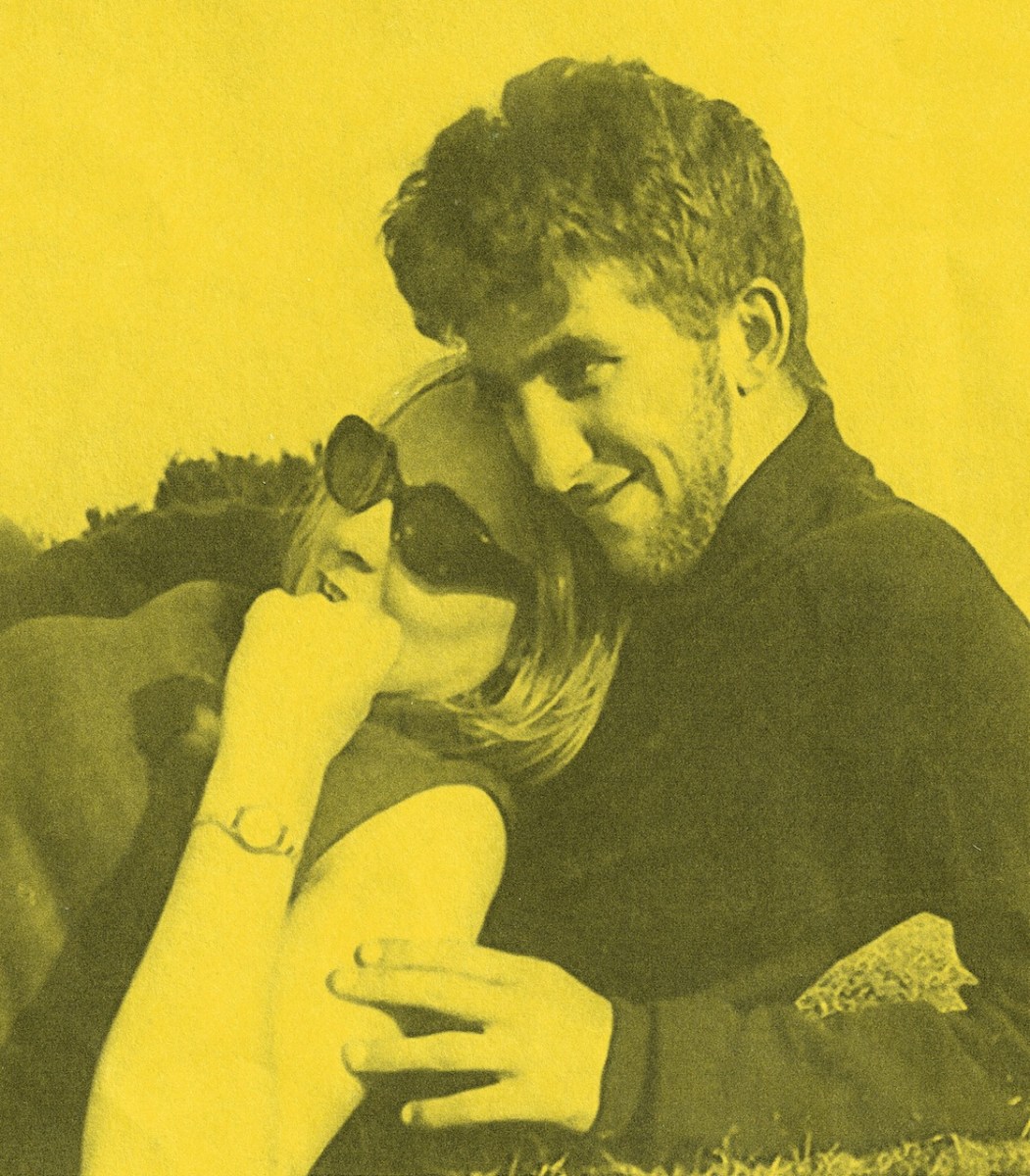

Noelle Verling (above) studied ceramics at Hammersmith College of Art. She and John met and married and – when they moved back to Ireland in 1971 – John & Noelle Verling established the Fergus Pottery in Dripsey in 1971 with Noelle as potter. She produced a wide range of domestic ware at Dripsey. When they moved in 1973 to Ballydehob to take over Christa Reichel’s studio, they adapted Reichel’s press-moulds and Gurteenakilla pottery stamp for their own work and from then on, traded as Gurteenakilla Pottery and latterly as Brushfire.

. . . The Verlings loved the windswept West Cork landscape and felt moved to record a disappearing environment. John’s paintings often depicted the doors, windows and walls of decaying buildings, repositories for the memories of past inhabitants, long gone. The windswept thorn tree is a familiar motif which connects John Verling with West Cork: the tree became his icon and frequently appeared in his paintings and on his ceramic work . . .

Alison Ospina – West Cork Inspires 2011

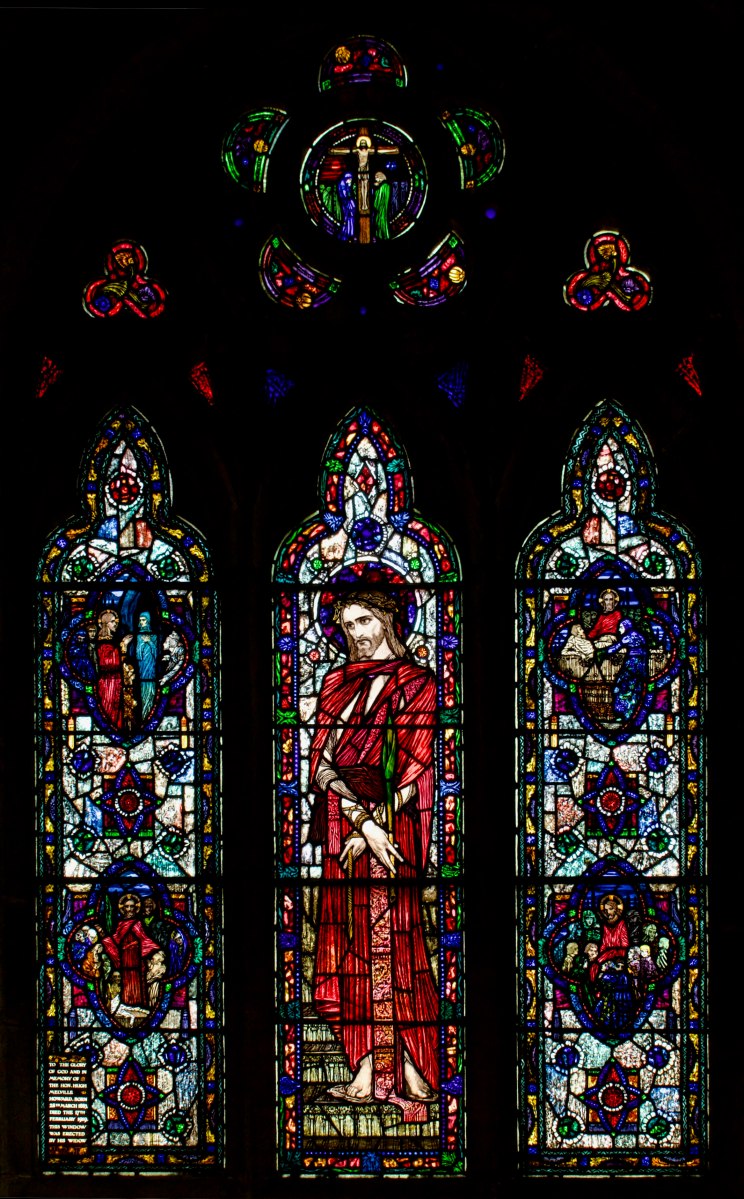

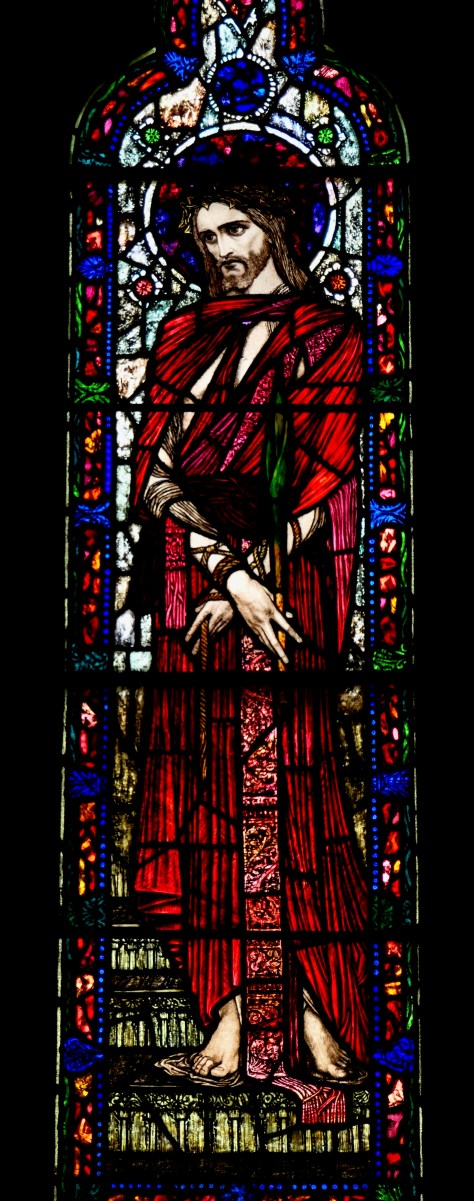

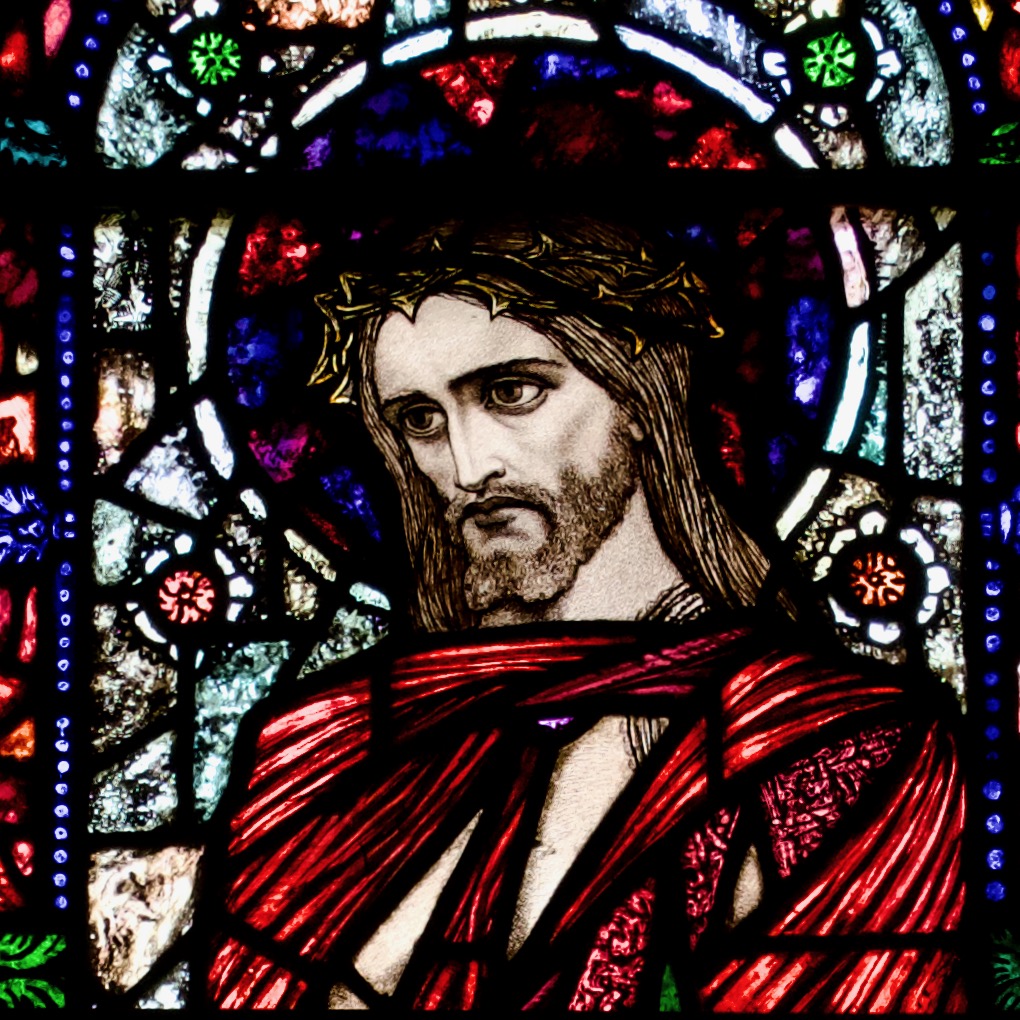

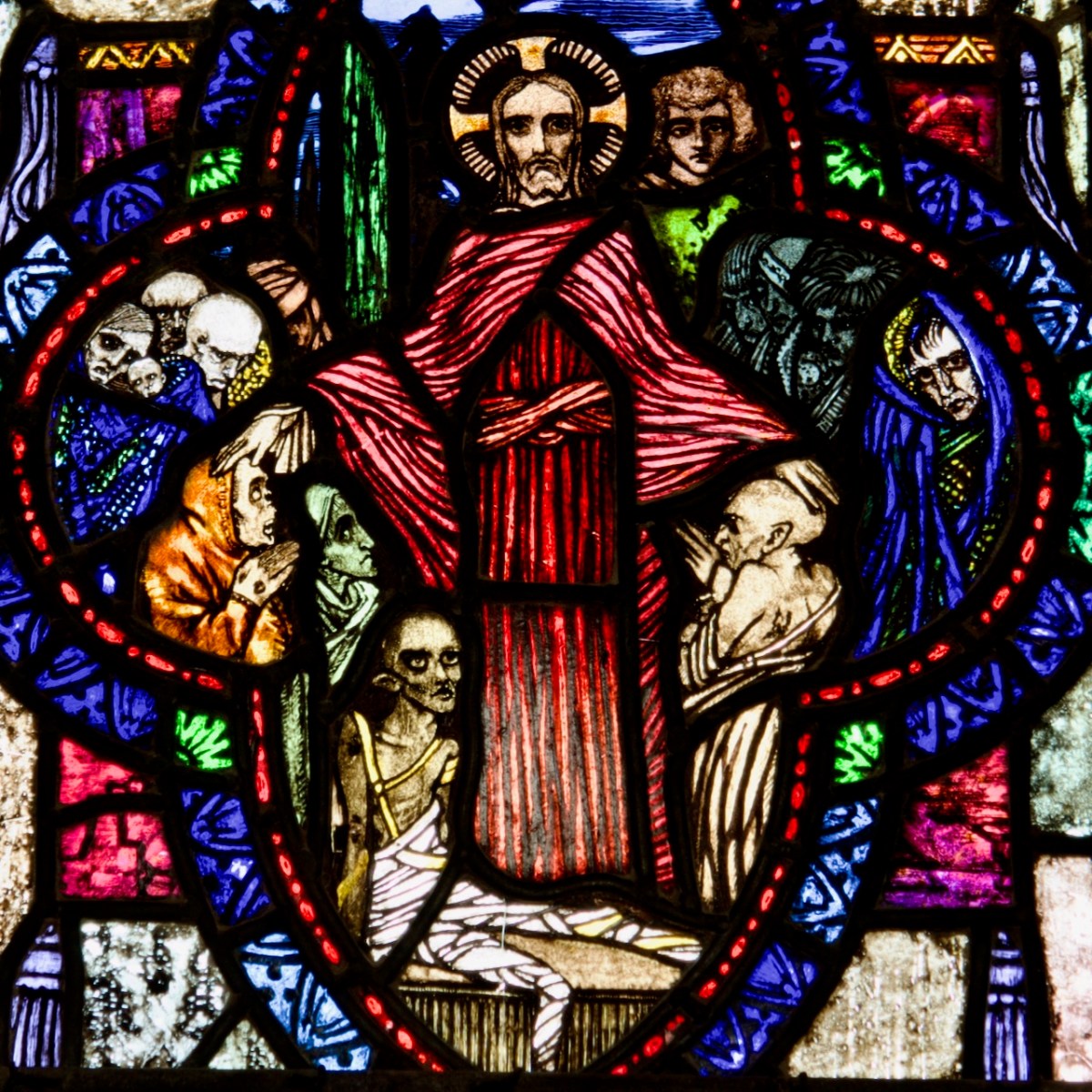

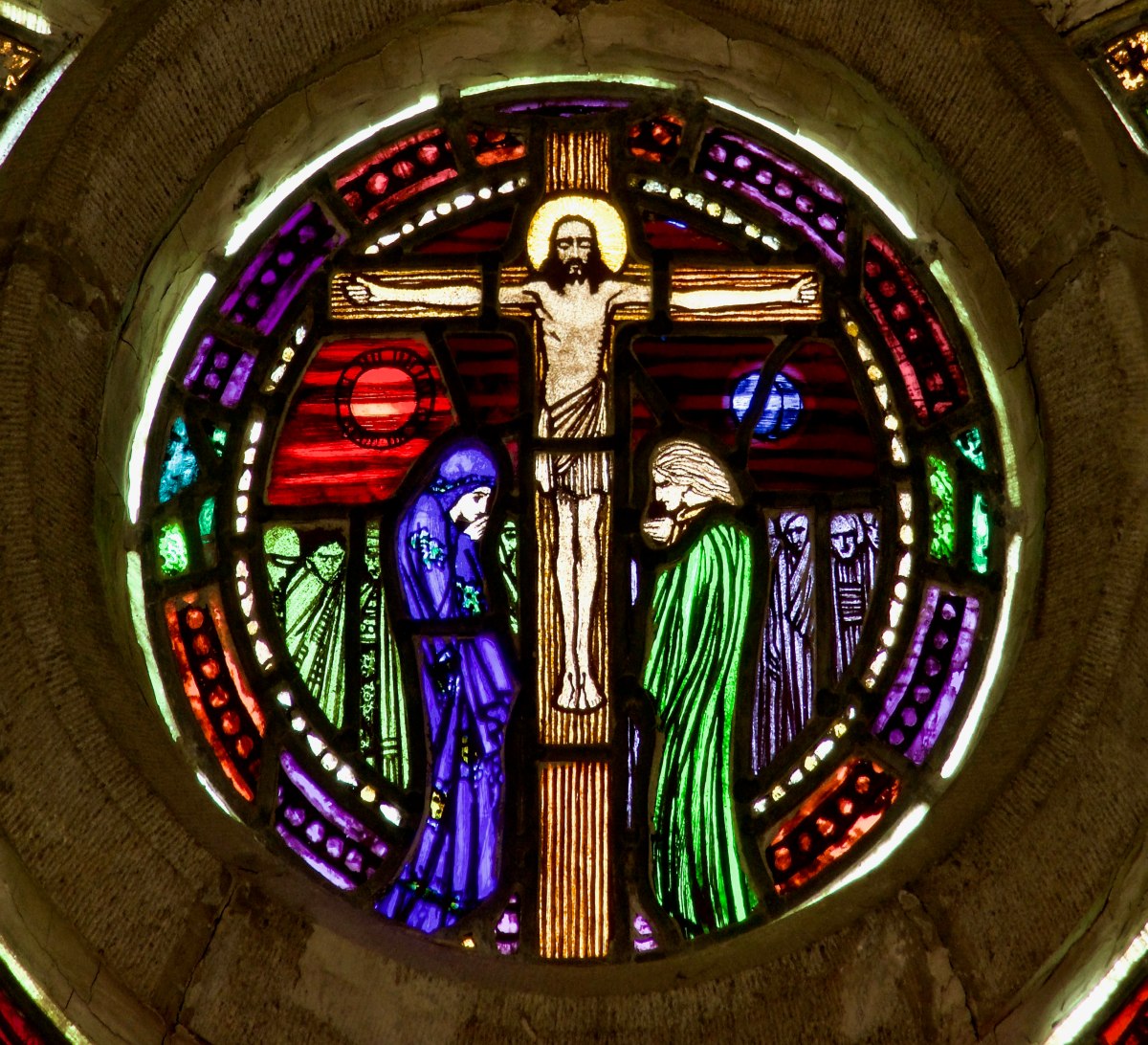

This is a rare photograph of John working on one of his favourite subjects: the gnarled thorn tree suffering from the ravages of harsh West Cork gales. Among the architectural work he undertook voluntarily was the reordering of the east end of St Bridget’s Catholic Church in Ballydehob. This was a major work.

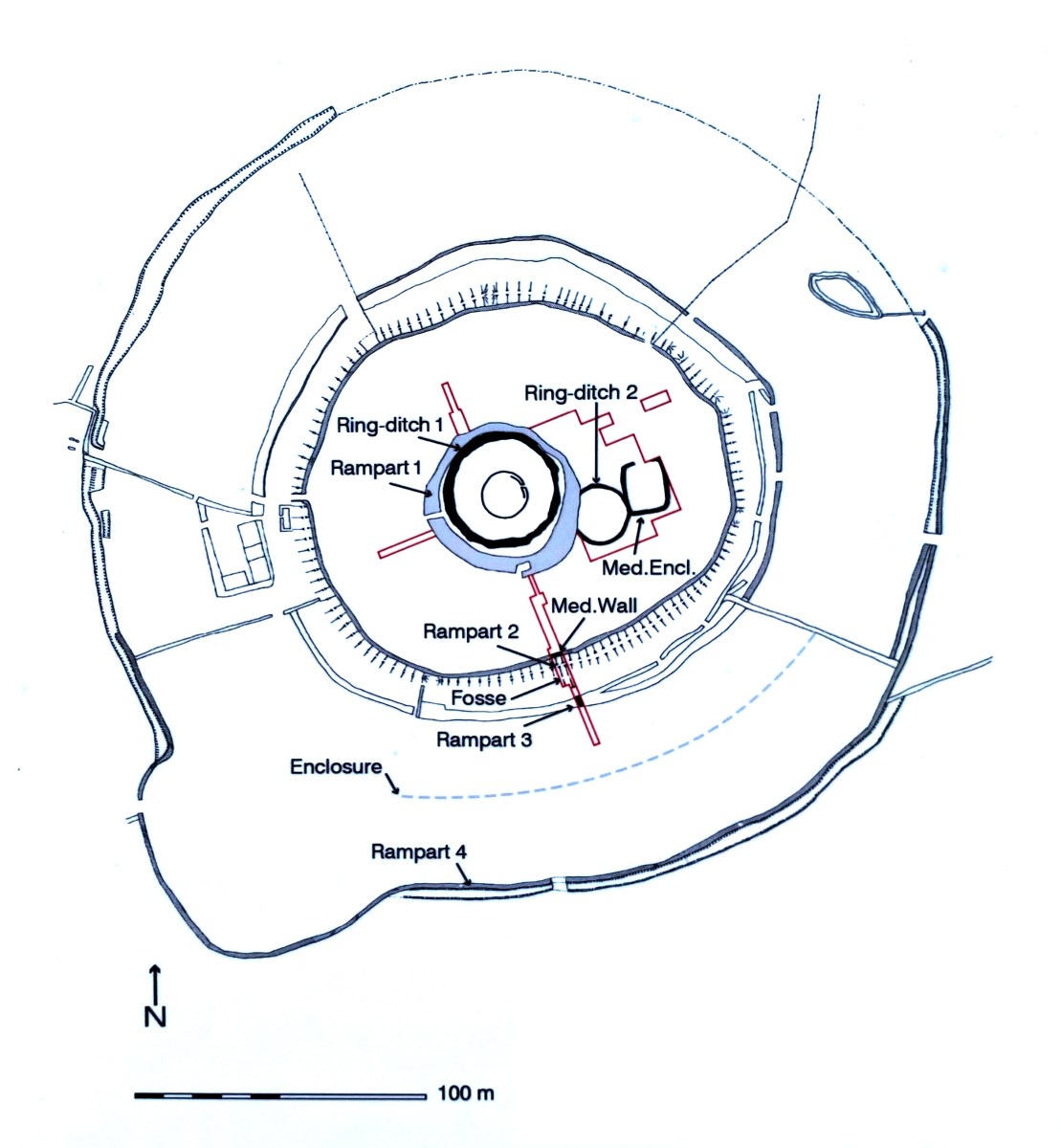

. . . The gold fish hand drawn in the background of the altar and the depiction of one fish swimming against the shoal continues to evoke admiration from locals and visitors alike. He also designed the two ‘windswept thorn’ stained glass windows and etched the brass surround of the tabernacle. The Altar slab, composed of a vast monolith like the capstone of a dolmen, is a distinguished piece of sculpture and a tribute to his imaginative capacity . . .

John Verling Website: https://www.johnverling.com

Special thanks to Geoff Greenham for giving us this superb photo of St Bridget’s Church, Ballydehob.

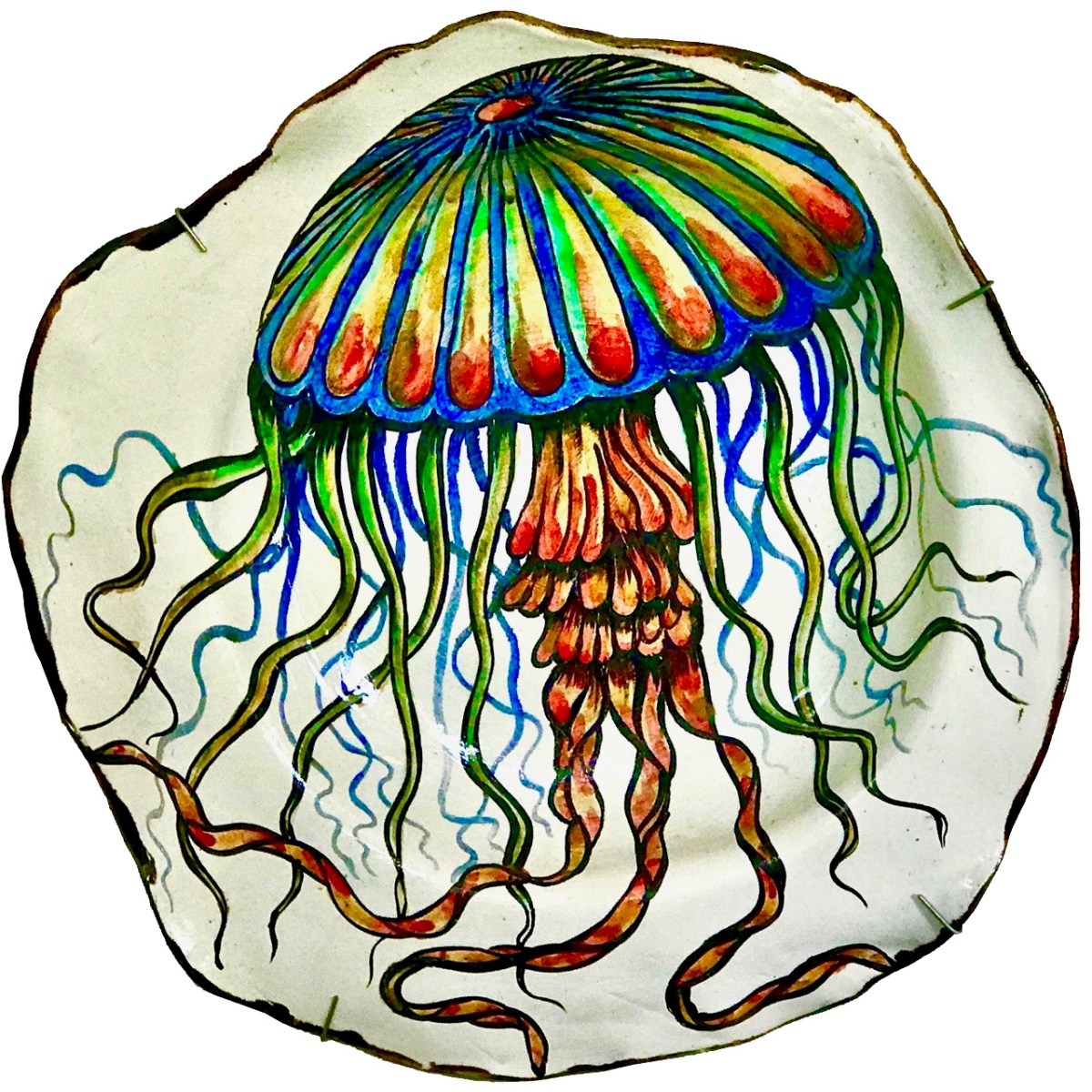

The sign for the Brush Fire Ceramics Pottery, created by Noelle and John. They successfully produced a large number of individual pieces, crafted and fired by Noelle, and decorated by John.

John Verling died in 2009. Noelle Verling is living in West Cork and has been extremely helpful in providing material and information for this exhibition. Without her we would have been unable to fully present this story.

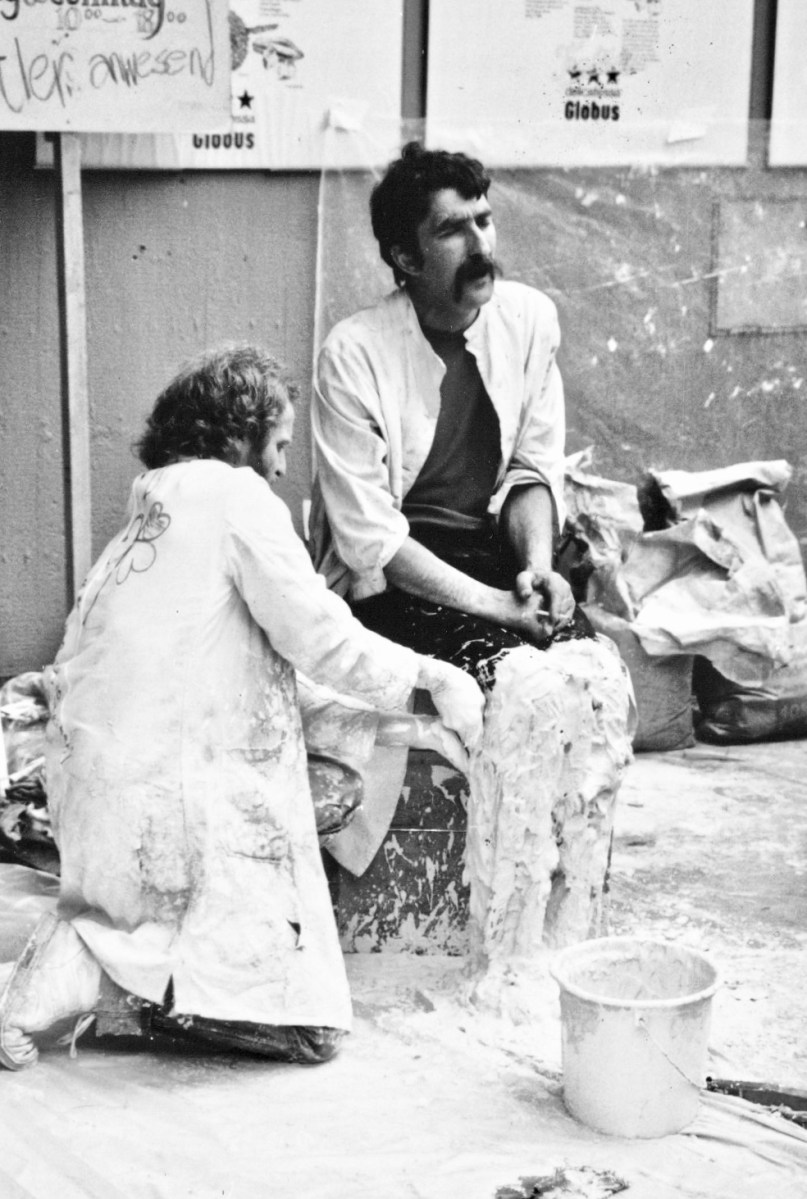

That’s John Verling in the picture above having his legs plastered by Ian Wright: this was part of a publicity stunt for the visit of a large group of West Cork artists to Zurich in 1985. John is also singing a folk song! You can read more about that particular enterprise here.

The Ballydehob Arts Museum is grateful to the town’s Community Council for providing the accommodation for the Museum. BAM is: Brian Lalor, Robert Harris, Sarah and Stephen Canty. Their combined knowledge and practical experience has ensured that our ambitions for this – our fourth exhibition – are fully realised.

Exhibition opens Jazz Festival Weekend in Bank House: Thursday 27 April @ 5pm, then Friday 28 April to Monday 1 May: 11am – 4pm. It will open with the Tourism Centre from June to September 2023