Mary Harris was born in Cork City in 1837. Like the lady herself, that’s a bit controversial: she claimed to have been born on 1st May 1830 – probably because that enabled her to celebrate her 100th birthday in 1930 – but also because the first day of May has always been associated with workers’ rights. She didn’t make a huge impact in Ireland, as she emigrated with her parents as a child. The first paragraph of her autobiography (published 1925 by C H Kerr + Co, Chicago) succinctly summarizes the early years of her life:

…I was born in the City of Cork, Ireland, in 1830. My people were poor. For generations they had fought for Ireland’s freedom. Many of my folks have died in that struggle. My father, Richard Harris, came to America in 1835, and as soon as he had become an American citizen he sent for his family. His work as a laborer with railway construction crews took him to Toronto, Canada. Here I was brought up but always as the child of an American citizen. Of that citizenship I have ever been proud…

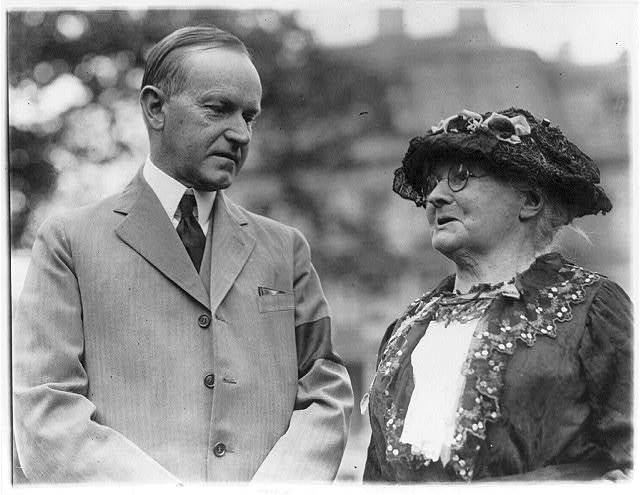

Mary Harris – Mother Jones – remembered in Cork (left) and in the US (right)

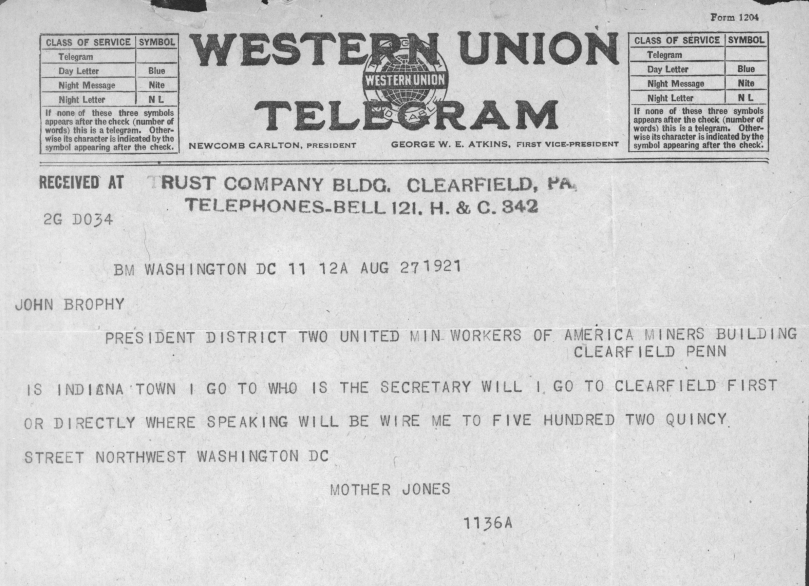

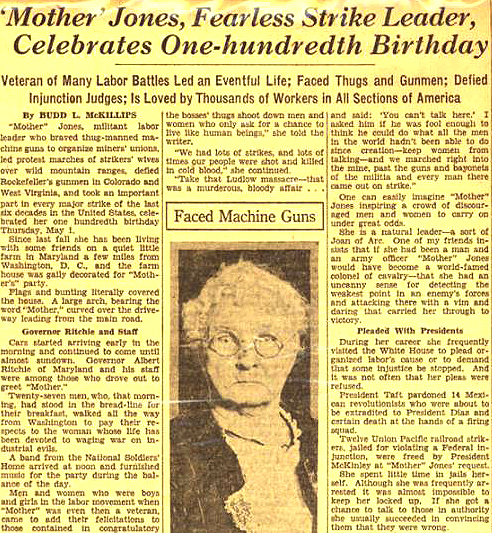

Mary was a ferocious socialist – perhaps influenced initially by her husband George E Jones, a member of the Iron Molders Union in Memphis. She lost her husband and four young children to a yellow fever epidemic in 1867, and seemed to take the emerging Labor Movement as her family thereafter. She re-created herself as ‘Mother Jones’ and spent the rest of her life supporting the rights of workers in the railroad, steel, copper, brewing, textile, and mining industries. The five foot tall white-haired Irish lady participated in hundreds of strikes all over America, and attracted public attention by mobilising miners’ wives to march with brooms and mops in order to block strikebreakers from entering the mines.

Mother Jones helped found the US Social Democratic Party (1898) and the Industrial Workers of the World (1905); she published articles in the International Socialist Review, met and lobbied (and gained the respect of) several Presidents and spent time in jail. On one occasion when violence broke out during a mine strike in West Virginia, a state military court convicted her of conspiracy to commit murder. Nationwide protest led the Governor to commute her twenty-year sentence.

Some quotations ascribed to Mother Jones:

A lady is the last thing on earth I want to be. Capitalists sidetrack the women into clubs and make ladies of them

Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living

My address is like my shoes. It travels with me. I abide where there is a fight against wrong

No matter what the fight, don’t be ladylike! God almighty made women and the Rockefeller gang of thieves made the ladies

I asked a man in prison once how he happened to be there and he said he had stolen a pair of shoes. I told him if he had stolen a railroad he would be a United States Senator

The employment of children is doing more to fill prisons, insane asylums, almshouses, reformatories, slums, and gin shops than all the efforts of reformers are doing to improve society

I’m not a humanitarian, I’m a hell-raiser

Strangely, Mary did not support the women’s suffrage movement in the United States: she considered it a middle class diversion taking the focus away from the fight against social injustice and basic universal rights for all workers. In her eighties she was still actively supporting strikes involving streetcar, garment and steel workers.

Mary Harris Jones died on November 30, 1930. After being celebrated by a mass in Washington DC, she was buried at the Union Miners’ Cemetery in Illinois, next to victims of the Virden, Illinois mine riot of 1898. Her funeral was attended by thousands of labour supporters, mine workers and other mourners.

Cork remembers this daughter of revolution: we found a commemorative plaque in the Shandon district, close to the old Butter Market – historically the city’s most notable industry. In the States her name lives on also: Mother Jones is an independent, non-profit making magazine and website reporting on politics, the environment, human rights, and culture ‘…that in its power and reach informs and inspires a more just and democratic world…’

MoJo – the liberal Mother Jones Magazine

Bravo, Mary Harris of Cork, for being so committed to the fight for the basic rights of humanity in general and the working population in particular. And watch out, capitalists and oppressors – as she is reported as saying frequently ‘…the kaisers of this country are next, I tell ye…’