‘Drowned Landscapes’ – that’s an adequate enough description for us to look again at a subject which RWJ covered five years ago in this post: Tralong Bay, Co Cork – give it a read. I was reminded of the subject when we took part in an Archaeology Festival based in West Kerry just a week ago: Amanda’s current holy well blog describes the expeditions. One of the sites visited was Bunaneer Drowned Forest, where we saw stumps of trees on the beach there which were alive thousands of years ago. At low tide many tree remains become visible at Bunaneer, near Castlecove village on the south coast of Kerry’s Iveragh Peninsula. Our guides for this expedition were plant biologist Calum Sweeney and archaeologist Aoibheann Lambe.

This large jumble of roots (above) is known as Goliath. All the remains here can be seen at regular low tides: at other similar sites elsewhere in Ireland, remains of ancient tree boles and roots are only revealed when tides are exceptionally low. I find it remarkable to be able to see and readily touch these archaic pieces of timber: we are communing with distant history!

Carbon dating has shown that these remains were alive between three and a half and five millennia ago. This is evidence that sea levels were significantly lower then, and that the shore line was further out – perhaps 50 metres from where we see it today. We are constantly – and quite rightly – being warned about rising sea levels resulting from our changing climate in the long term: here we see clear verification that it’s a continuing – and now apparently accelerating – process.

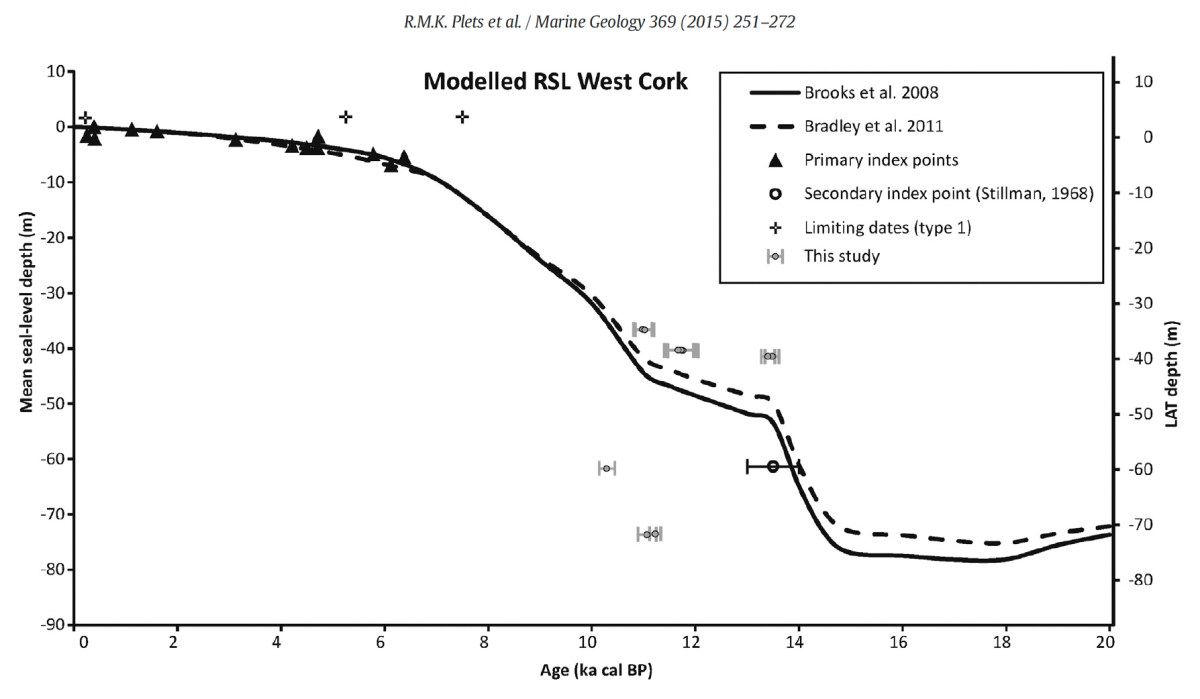

Our friends Robin and Sue Lewando were also on this expedition. Robin has a particular interest in sea-level changes in the Late Quaternary and subsequent eras, and he pointed me to a 2015 paper which explores the subject specifically in the Bantry Bay area of West Cork. That’s a good place to be looking at ancient history: remember the story of Cessair – Noah’s daughter-in-law – who came ashore at Donemark? You first read about it here! So this is a scientific diagram which sets out how sea-levels have been changing over time in our locality:

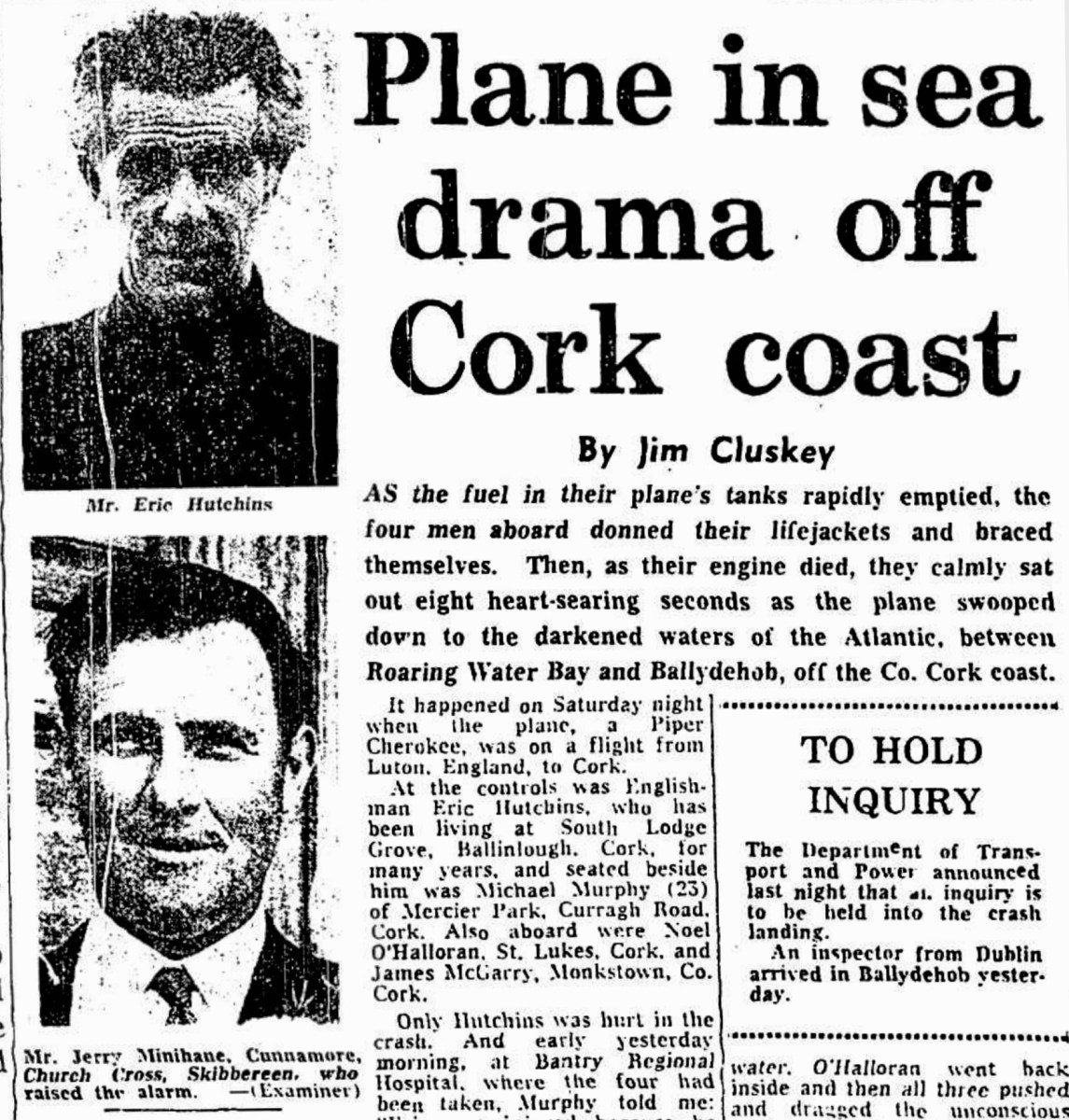

It’s an interesting comparison to take our horizons wider in our study of changing sea levels across the islands of Ireland. Over on the east coast – north of Bray, Co Wicklow – there is another substantial area where tree remains have been revealed at certain tidal conditions.

Above are the areas of beach between Bray and Killiney where ‘drowned forest’ remains have been observed. While at Youghal, Co Cork, further finds have occured:

This example catches our interest because the name of the settlement – Youghal – is derived from the Irish word ‘Eochaill’ meaning ‘Yew Woods’: they were evidently once common in the area, leading us to wonder whether the tree remains in this instance are of yew. In 2014 the following account of another ‘ancient drowned forest’ discovery appeared in the Irish Times (photograph courtesy of Joe O’Shaughnessy):

. . . Walking out on to the shoreline at low tide, geologist Prof Mike Williams points to the oak, pine and birch stumps and extensive root systems which were once part of woodlands populated by people, wolves and bears. These woodlands extended out into lagoons and marshlands that pre-dated the formation of Galway bay, Prof Williams says.

An extensive layer of peat also exposed at low tide in the same location in Spiddal was formed by organic debris which once carpeted the forest floor. The stumps at Spiddal are surrounded by root systems which are largely undisturbed. The carpet of peat is covered in strands of a reed called phragmites, which can tolerate semi- saline or brackish conditions.

“These trees are in their original growth position and hadn’t keeled over, which would suggest that they died quite quickly, perhaps in a quite rapid sea level rise,” Prof Williams adds. Up until 5,000 years ago Ireland experienced a series of rapid sea level rises, he says. During the mid-Holocene period, oak and pine forests were flooded along the western seaboard and recycled into peat deposits of up to two metres thick, which were then covered by sand.

Prof Williams estimates that sea level would have been at least five metres lower than present when the forests thrived, and traces of marine shell 50cm below the peat surface suggest the forest floor was affected by very occasional extreme wave events such as storm surges or tsunamis. He says most west coast sand-dune systems date to a “levelling” off period in sea level change about 5,000 years ago. Dunes in Doolin, Co Clare, are older still, having first formed around 6,500 years ago.

Prof Williams has located tree stumps in south Mayo and Clare, along with Galway, which have been carbon dated to between 5,200 and 7,400 years ago at the chrono centre at Queen’s University, Belfast. Some of the trees were nearly 100 years old when they perished . . .

Lorna Siggins

Irish Times 07/03/2014

Goliath, West Kerry, November 2023