WordPress, to my dismay, has now labelled all the content on this blog as ‘by Finola’. This is due to the necessity, for various reasons, of adjusting ‘ownership’ and management parameters. It’s a bit heartbreaking, though, as it’s no longer easily discernible which of the posts (approx half of the 1,132 posts so far) were written by Robert. So every now and then I thought it would be good to highlight one of his older posts. So here is his wonderful account, written originally in 2014, and titled In Search of Ghosts, of the spirits that haunt Brow Head.

Lonely and wild – Brow Head is the most southerly point on the mainland of Ireland. There are ghosts here: ghosts of ancient people who created the stone monuments, perhaps 5000 years ago, that are now inundated by every tide in the bay at Ballynaule below this Irish ‘Lands End’; ghosts of early farmers who began to lay out field boundaries criss-crossing this windswept promontory; ghosts of the defenders of an empire who feared a French invasion that never happened; ghosts of the prospectors who sunk two shafts – now barely protected by rusting wire – during the nineteenth century copper mining era; and, lastly, ghosts of the pioneers of our own digital age, represented in the brooding ruins that crown the hilltop here above West Cork’s remotest village, Crookhaven.*

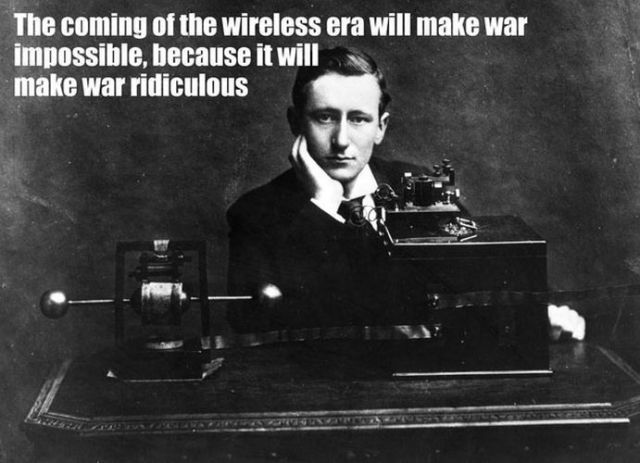

We can be very specific about one ghost: Guglielmo Marconi – born at Bologna, Italy, on April 25, 1874 to Giuseppe Marconi, an Italian country gentleman, and Annie Jameson, daughter of Andrew Jameson of Daphne Castle, Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland. The Jamesons were and are renowned distillers of Irish Whiskey. It’s reasonable to say that Marconi was an ‘Irish Italian’, and that heritage was reinforced when in 1905 he married Beatrice O’Brien, daughter of the 14th Baron Inchiquin. Marconi’s fame is that he pioneered the commercial application of electromagnetic waves – or Radio.

At the age of twenty one, Marconi was able to demonstrate to his father how, without any visible physical link (without wires), he could transmit dots and dashes through the rooms of their home in Pontecchio. “…When I started my first experiments with Hertzian waves…” he is quoted as saying, “…I could scarcely believe it is possible that their application to useful purposes could have escaped the notice of eminent scientists…” His parents used their influence to help him travel to England to meet the Engineer-in-Chief of the British Post Office with the result that in 1896 Marconi obtained the first ever patent in wireless telegraphy.

Marconi’s ambitions started in a room in Italy: by December 1901 he was able to send messages from Poldhu, Cornwall, to St John’s, Newfoundland, a distance of 2100 miles – an historic achievement. In his attempts to bridge the Atlantic with Radio waves he had explored the west coasts of Britain and Ireland for suitable telegraphic locations. One of his destinations was Crookhaven, which he visited many times – using the Flying Snail en route!

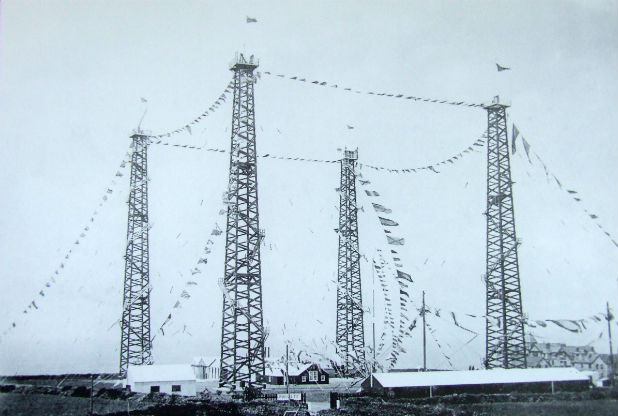

Brow Head was one of a number of transmitting stations set up by Marconi and it got off to a flying start soon after opening in 1901 when, in the presence of Marconi himself, Morse signals were received from Poldhu, 225 miles away. The fact that the Atlantic gap was conquered only a few months after this shows the rapid pace of developments at that time.

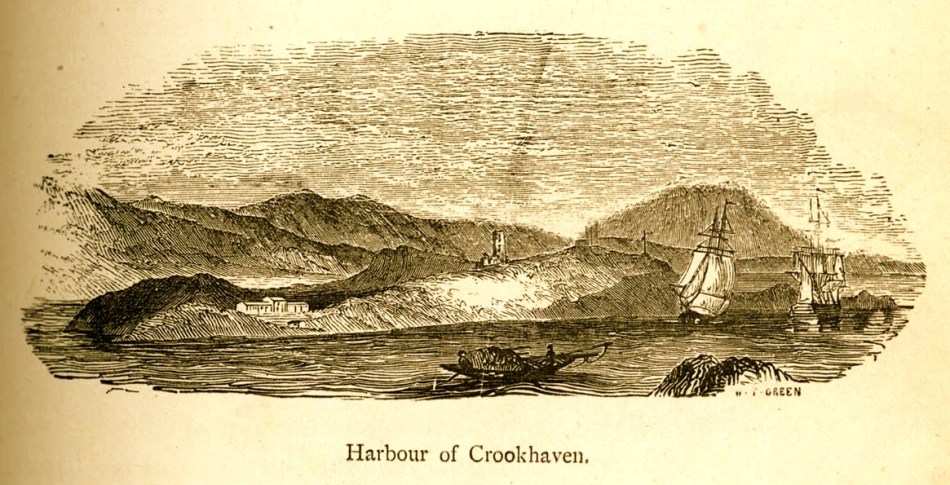

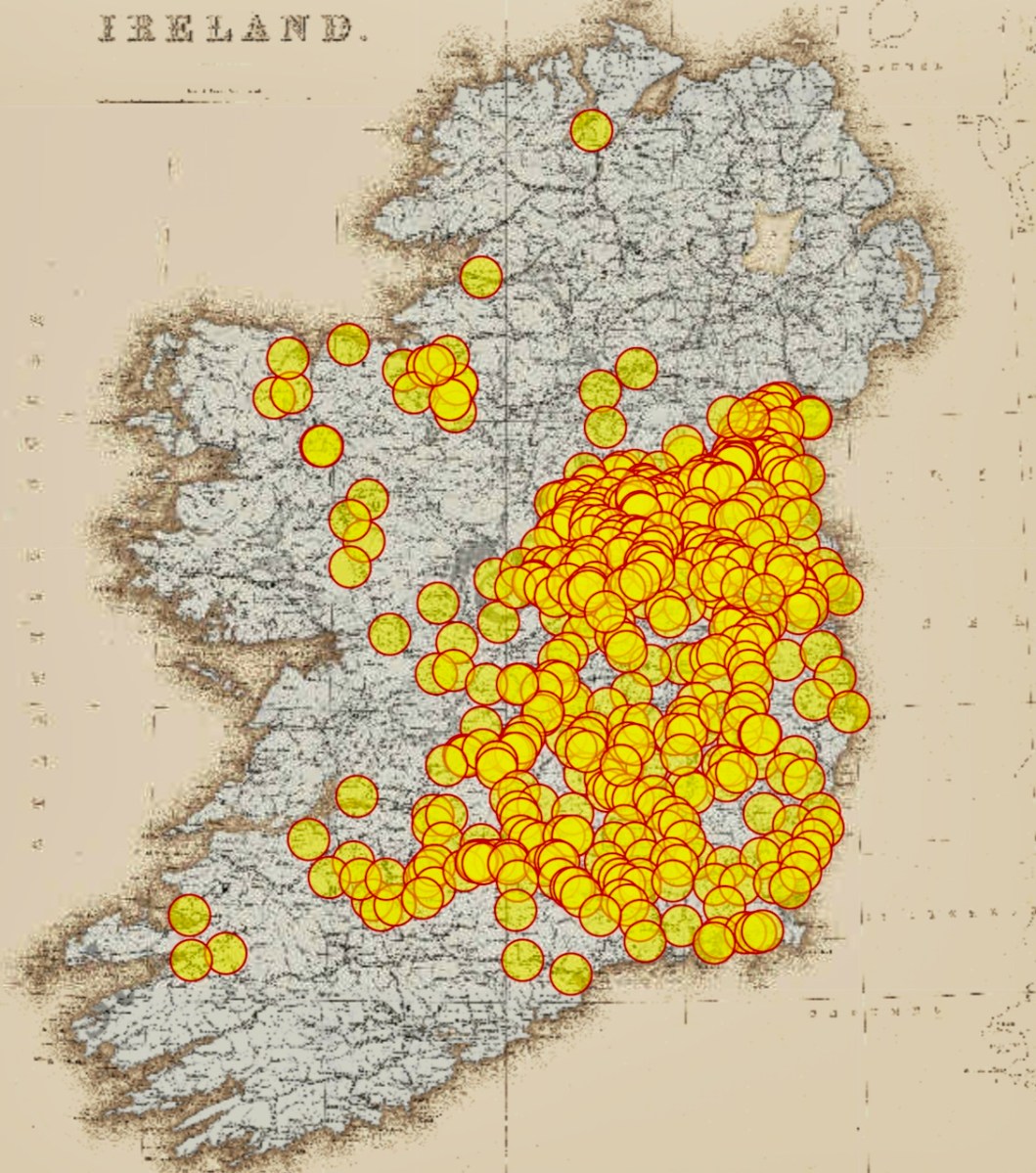

The village of Crookhaven had long been the first and last port of call for ships going between Northern European ports and America. Over the centuries ships stocked up here with provisions before tackling the open sea. Because of this, the major shipping lines had agents here. Reuters and Lloyds had flag-signalling and semaphore equipment on Brow Head to communicate with the maritime traffic, superseded by the telegraph station. At the end of the 19th Century it was said that “…you could cross the harbour on the decks of boats…” Up to 700 people are reputed to have lived in the area at that time: now, Crookhaven has a permanent population of no more than 40. An article written by one of the telegraph operators in 1911 summarises:

…As Crookhaven is the first station with which the homeward bound American liners communicate it is naturally a busy station. By the aid of wireless all arrangements are made for the arrival of the ships, the landing and entraining of the passengers and mails, whilst hundreds of private messages to and from passengers are dealt with. Messages are also received from the Fastnet Lighthouse, which is fitted with wireless, reporting the passing of sailing ships and steamers. These messages are sent by vessels not fitted with wireless by means of signals to the Fastnet, thence by wireless to Crookhaven, whence they are forwarded to Lloyds and to the owners of the vessels…

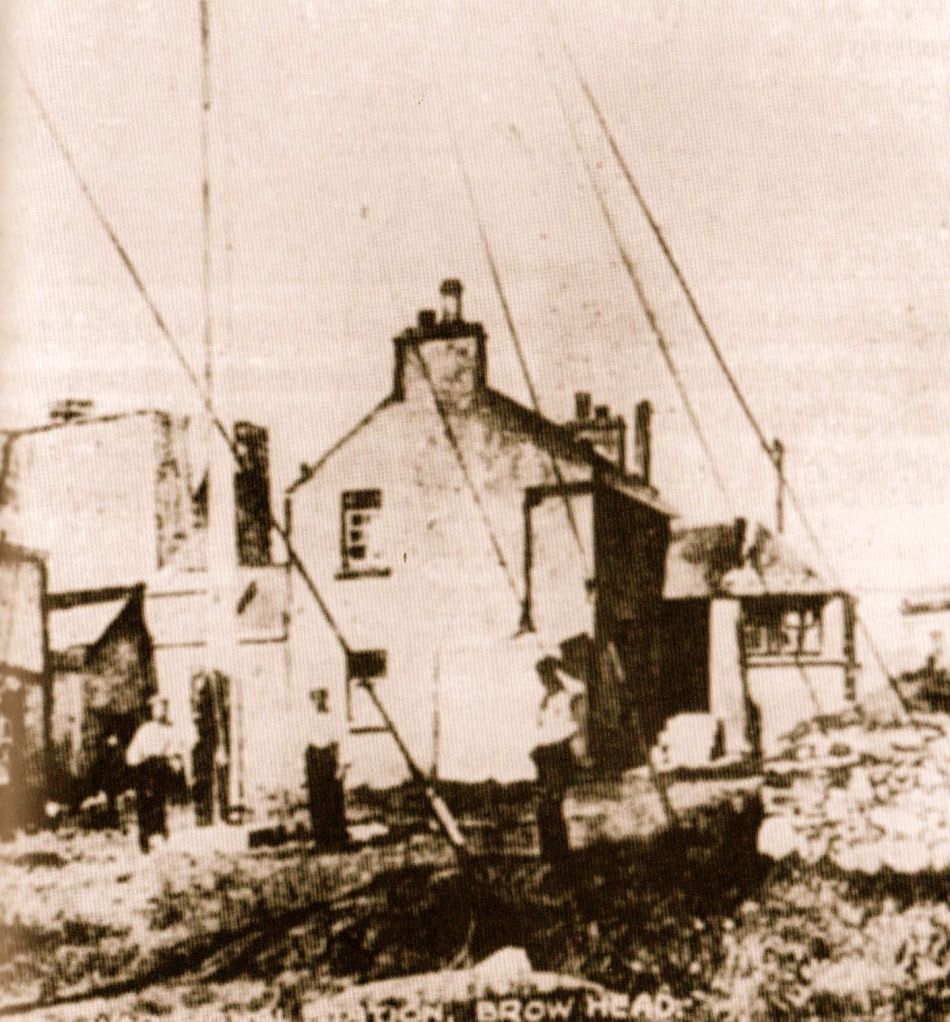

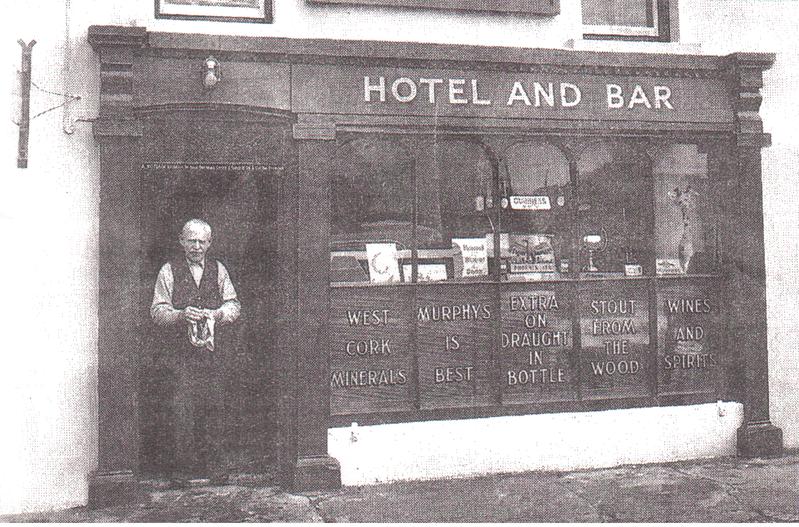

We have some first hand accounts of the workings of the signal station in its heyday from the handwritten log books of Arthur Nottage – for many years landlord of the Welcome Inn at Crookhaven – who died aged 90 in 1974. In 1904 he arrived in West Cork (from England) to work on a shift basis with one other man as Marconi telegrapher at Brow Head. Until 1914 he operated the Morse code apparatus with a salary – generous for the time – of £1 per week.

A hundred years ago telegraphy had advanced to such a stage that it was no longer necessary for stations to operate close to the shipping lanes, and small, isolated sites such as Brow Head were closed down. Legend has it that in 1922 the Irregulars destroyed the buildings during the Civil War.

Finola and I have both been inspired by the landscape and atmosphere of this Atlantic frontier. It’s a place we will return to. All West Cork landscapes are impressive, but this is a place apart. If you want to feel at the end of the world, walk here: you won’t meet many others, even in the height of the visitor season. Perhaps that’s because it’s haunted – but in the best possible way. Like so much of Ireland the world has come here – a mark has been made – memories have been left behind. Now, you hear the ghosts in the ever-present currents of wind and surf.

*I am grateful to Michael Sexton and the Mizen Journal (Number 3 1995) for many fascinating items on the Crookhaven Telegraph Station not recorded elsewhere.