We have been in Kerry a few times this year and visited three stunning sites – Staigue (above), Leacanabuaille and Cahergal (sometimes written Cahergall) – all of which fit the definition of stone forts, often referred to as Cashels. For non-Irish readers, cashel is pronounced the same way as castle, but with the sh sound in the middle – don’t say cash-elle.

Each of these also fit in to a category that has been labelled by archaeologists as the Western Stone Forts, and they were the subject of research by the Discovery Program several years ago. The forts included under this title, about 25 in all, dotted along the western seaboard, were chosen because of their their large size, or prominent location or because they have complex or massive defensive features.

In a fascinating talk available to view online, archaeologist Claire Cotter walks us through several examples of such forts. In relation to size, she points out the huge investment in effort to build those walls, once you go over about 2 metres in height. Of course the walls have to be very thick as well, to carry the weight of all that rock and to ensure they didn’t fall over. Inside, a feature of Staigue and Cahergal are the stone staircases arranged in a X shape – they make for a strong visual statement. Leacanabuaile (below) has stepped levels on the inside of the walls to give access to the parapet. Let’s take a look at each fort in turn to see what’s unique and what’s common among the three of them.

We’ll start with Leacanabuaile, pronounced Lacka – na – boolya and meaning the flagstones of the enclosure, or possibly the flagstones of the summer pasture. Large flagstones, or leacs, do litter the way up to the fort.

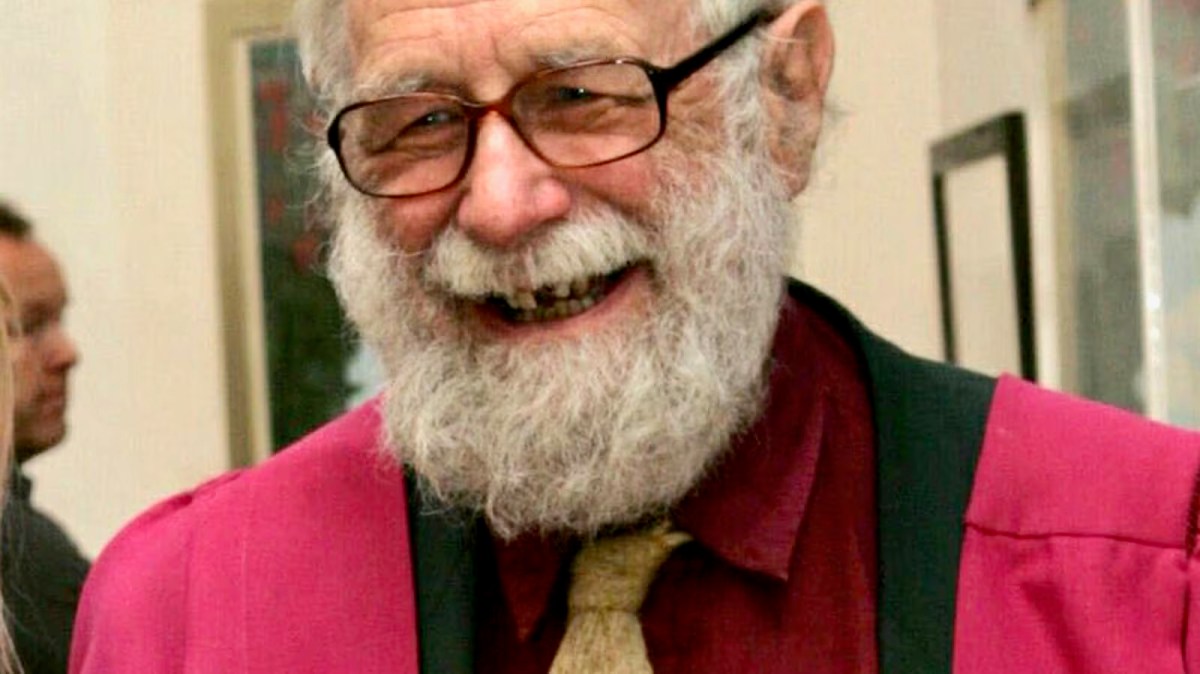

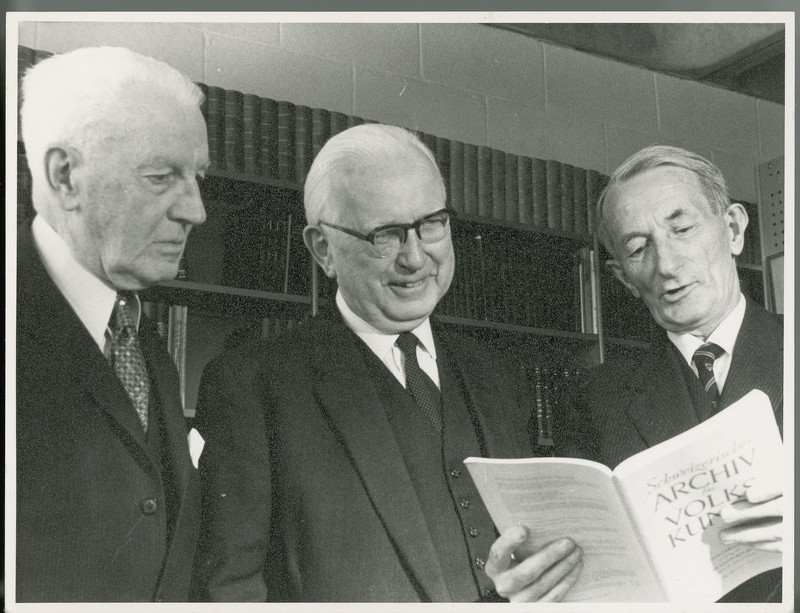

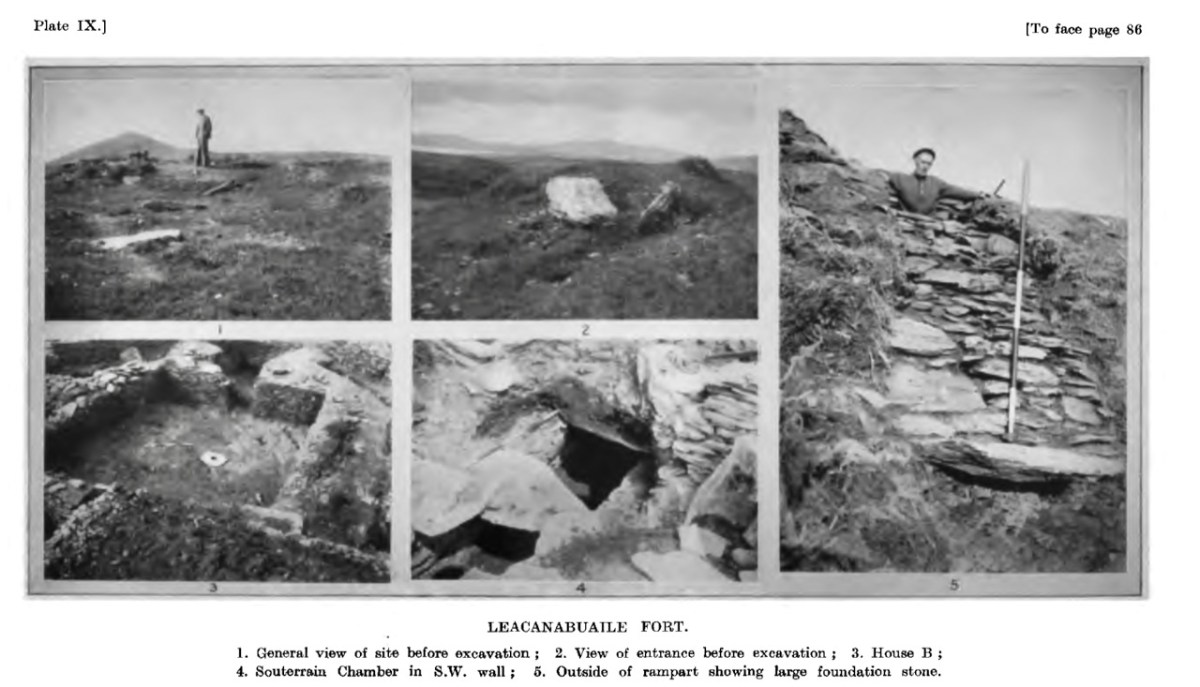

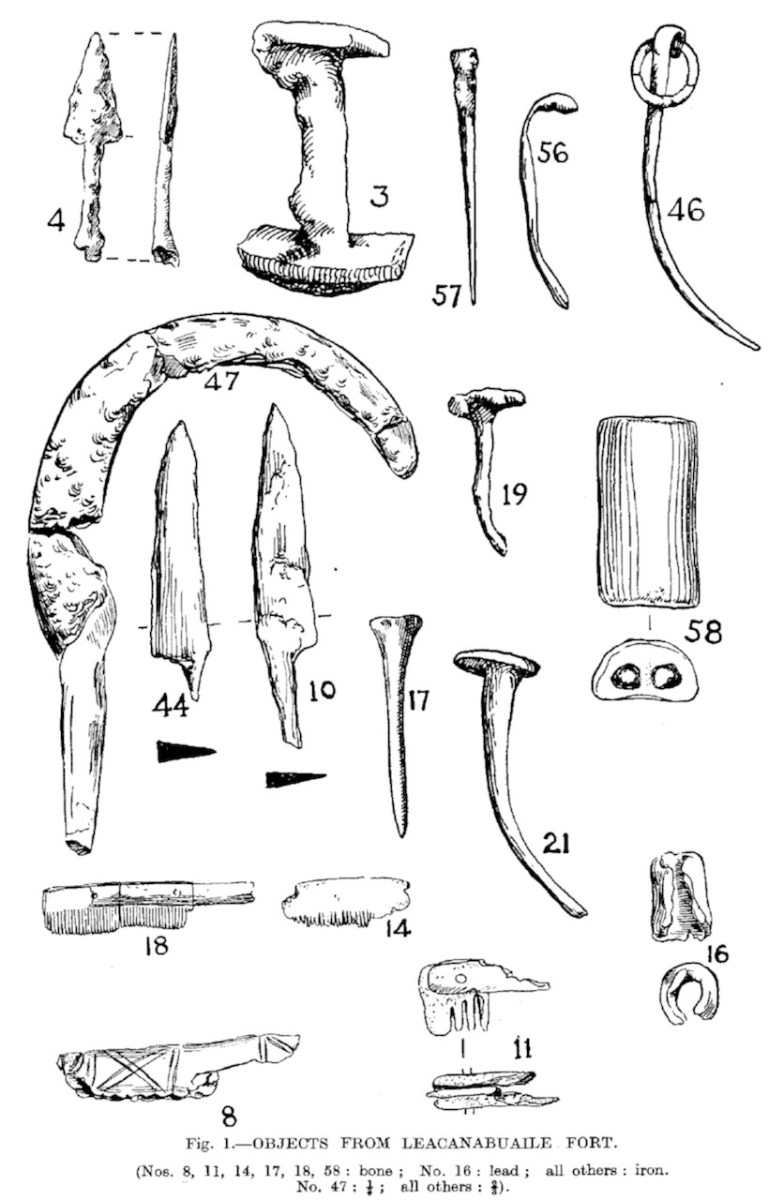

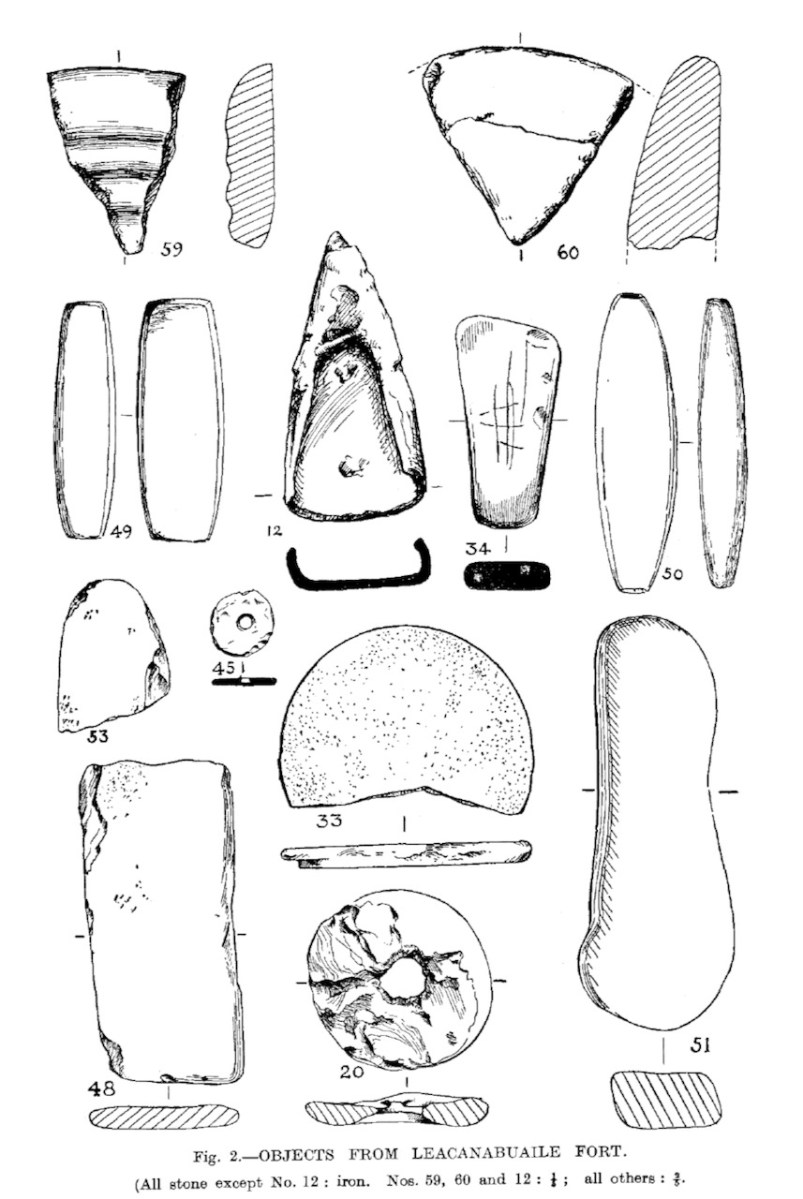

Leacanabuaile was excavated in the summers of 1939 and 1940 by Sean P Ó Ríordáin and J B Foy. Ó Ríordáin was a revered Irish archaeologist and his book, Antiquities of the Irish Countryisde was our text for first year in the Archaeology Department at UCC, where he had been the professor before O Kelly. That’s Ó Ríordáin in the middle, below at the Lough Gur dig in Limerick, with O Kelly furthest to his left. As an aside, he was married to Gabriel Hayes, the sculptor – one of her major works is mentioned in this post. She did the drawings of the finds, which you will see further down.

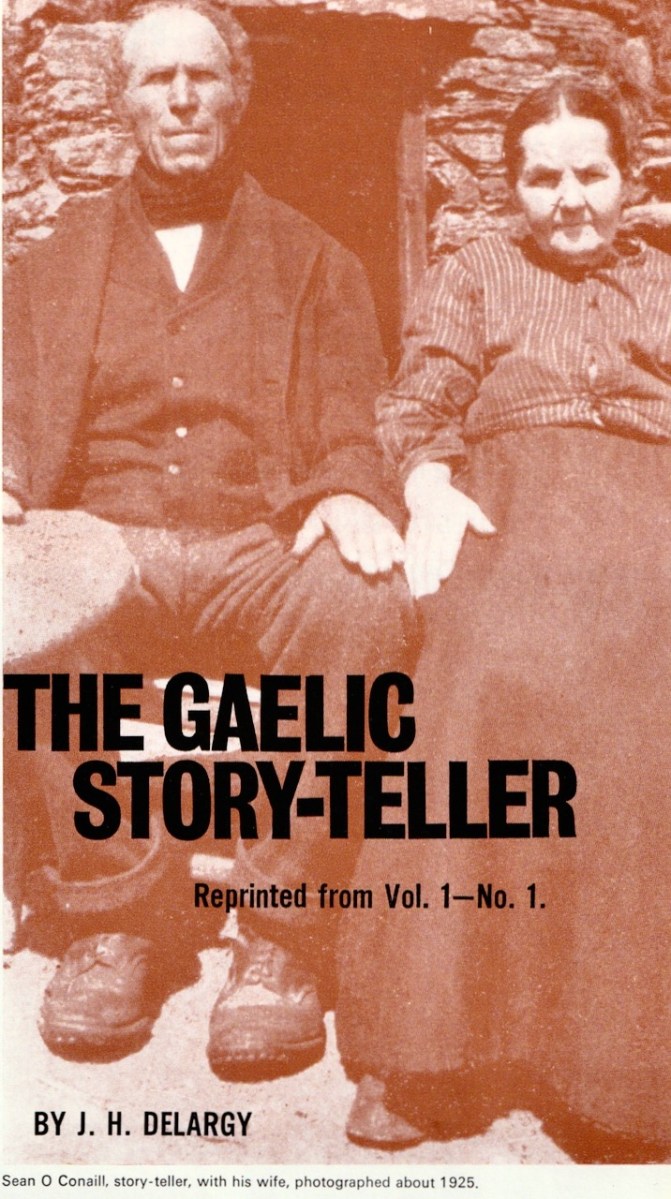

For most of the following, and all the quotes, I am taking the information from the excavation report, which was published in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society for 1941. The marvellous CHAS has made their old journal available online, and this report is here. Leacanabuaile is situated in the middle of a concentration of forts, close to Caherciveen and all within a mile or two of each other, and in the case of Cahergal, in clear sight, as you can see below.

Before the excavation it was in very poor condition – the walls had collapsed and it looked more like an earthen ringfort, with just traces of the stone wall showing through here and there. It was so unremarkable, in fact, that it was left off the Ordnance Survey maps.

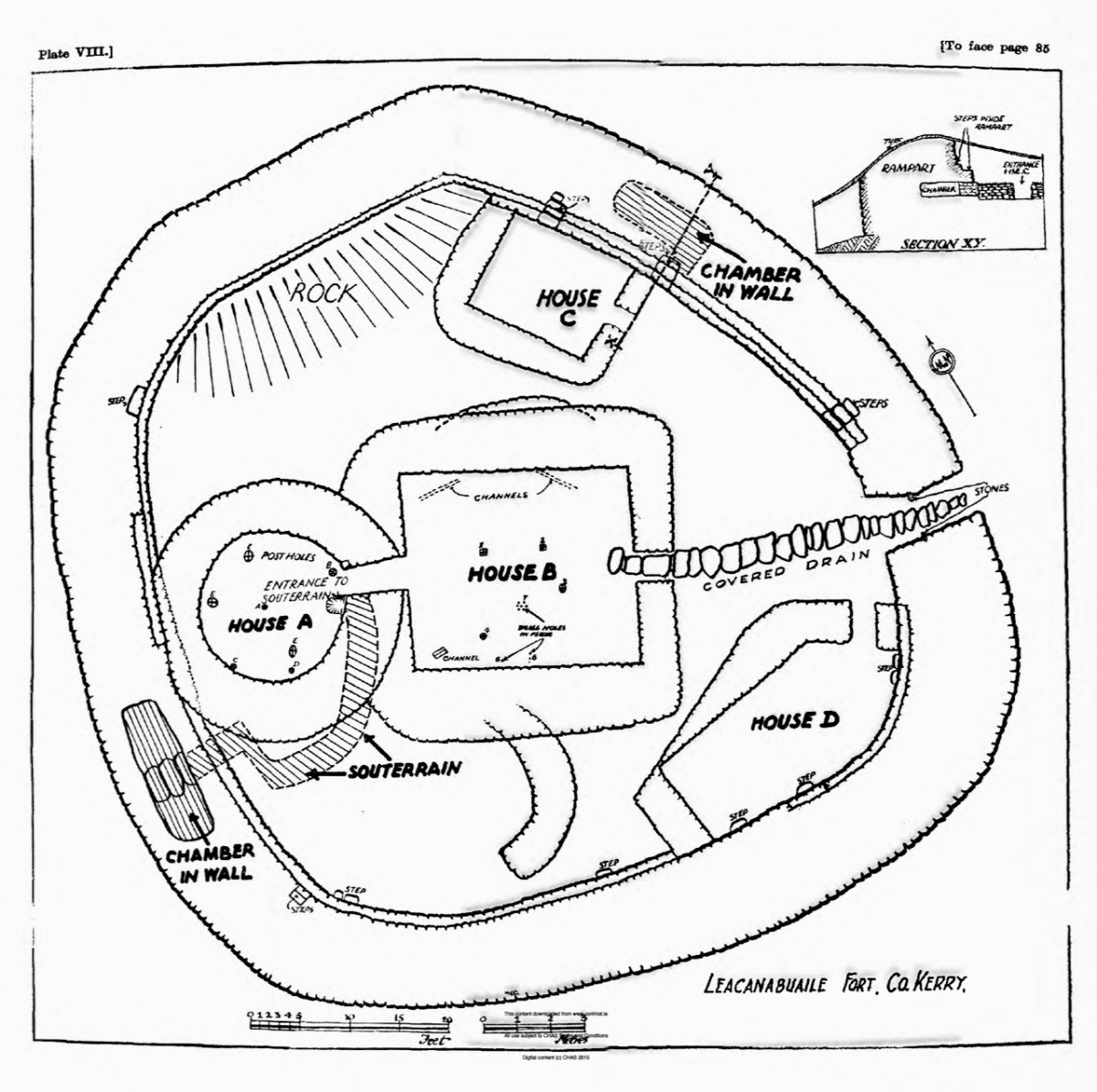

The excavation uncovered not only the massive nature of the walls, but four houses inside, a souterrain, and mural chambers. This was before the commonplace use of radiocarbon dating in Ireland so the usual way of dating a site like this was through the finds and through comparison with similar sites. Using these methods, Ó Ríordáin says:

The close dating of the Leacanabuaile site is not possible, but it may be noted that the finds correspond to material from sites dated by more significant objects to the ninth and tenth centuries AD.

The fort is not quite round and this was due to the undulation of the rocky hilltop on which it was built, the builders having to work around the steep slopes. The souterrain and the mural chambers were built at the same time as the walls.

Of the houses inside the fort, three were built at the same time as the fort – round house A and two others which now lie under house B. Houses D and C were the last to be built.

In regards to the material cultural objects found during the excavations, and what they reveal about the inhabitants, Ó Ríordáin states

Elaborate brooches and glass objects, for instance are notable by their absence. Bronze is rare and there is no evidence of its having been worked on the site – crucibles are not forthcoming: iron working is evidenced by the iron slag found. On the other hand, the inhabitants were probably quite well provided with the more vital necessities of life. They had . . . a dual source of supply – the sea and the land. The plough-sock and the querns show show that grain was cultivated, the bones show that domestic animals were kept and eaten, while the fare was added to by the collection of shellfish from the coast and by the capture of birds, particularly sea-birds.

The sea birds included heron, duck, goose, cormorant, puffin and razorbill, while the domestic animals were ox (most numerous), sheep, and pig. Also found were evidence of horse, dog and red deer.

What we see on the ground today is the result of conservation work undertaken by National Monuments as Leacanabuaile was taken into state care. Ó Ríordáin describes how

. . .the walls of the fort and the enclosed buildings were restored by building up, to some extent, the destroyed portions, so as to provide a level top surface which should stand the better the ravages of time. The lines of the old work have been carefully followed and the new building has been marked off from the old with a thin line of concrete. . .[stone objects] were set in cement in House B, so that they may be conveniently inspected.

So – what you see now at Leacanabuaile is as a result of the excavation and the subsequent conservation by National Monuments. Ó Ríordáin remarks, the skill with which the workmen used the material to build in the old manner is a good example of the survival of a technique in a given environment. That reminded me of our own experience with Building a Stone Wall. I also regretted that I hadn’t read the report before I visited so that I could find that thin line of concrete and take a photograph of it for this post.

We’ll take a look at Cahergal next, also excavated, this time by our friend Con Manning in the 1980s and 90s. This is a more complex site and the report is much longer so it will be a challenge to summarise in a blog post, but I’ll do my best.