Story 1. Bobbie

The first story is about a boy, Bobbie Bole, a student at Drogheda Grammar School in the 1940s. He’s the part of this account we don’t know much about, but he must have been a special boy. When he died, in 1942, many people donated money to create a memorial in his memory. It was decided that a stained glass window would be a good way to remember him,

Story 2: The Competition

The school established a competition for the window, and invited stained glass artists to submit designs. The subject was to be Christ Among the Doctors, also known as The Finding in the Temple. Here’s the story, from the King James Version (just because I love the language of it):

Now his parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the passover. And when he was twelve years old, they went up to Jerusalem after the custom of the feast. And when they had fulfilled the days, as they returned, the child Jesus tarried behind in Jerusalem; and Joseph and his mother knew not of it. But they, supposing him to have been in the company, went a day’s journey; and they sought him among their kinsfolk and acquaintance. And when they found him not, they turned back again to Jerusalem, seeking him. And it came to pass, that after three days they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them, and asking them questions. And all that heard him were astonished at his understanding and answers. And when they saw him, they were amazed: and his mother said unto him, Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing. And he said unto them, How is it that ye sought me? wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business? And they understood not the saying which he spake unto them. And he went down with them, and came to Nazareth, and was subject unto them: but his mother kept all these sayings in her heart. And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man.

It’s a Biblical Verse that is, for obvious reasons, associated with students and scholarship, making it an appropriate subject for this occasion. It’s been the subject of many famous paintings, including this one by Albrecht Dürer.

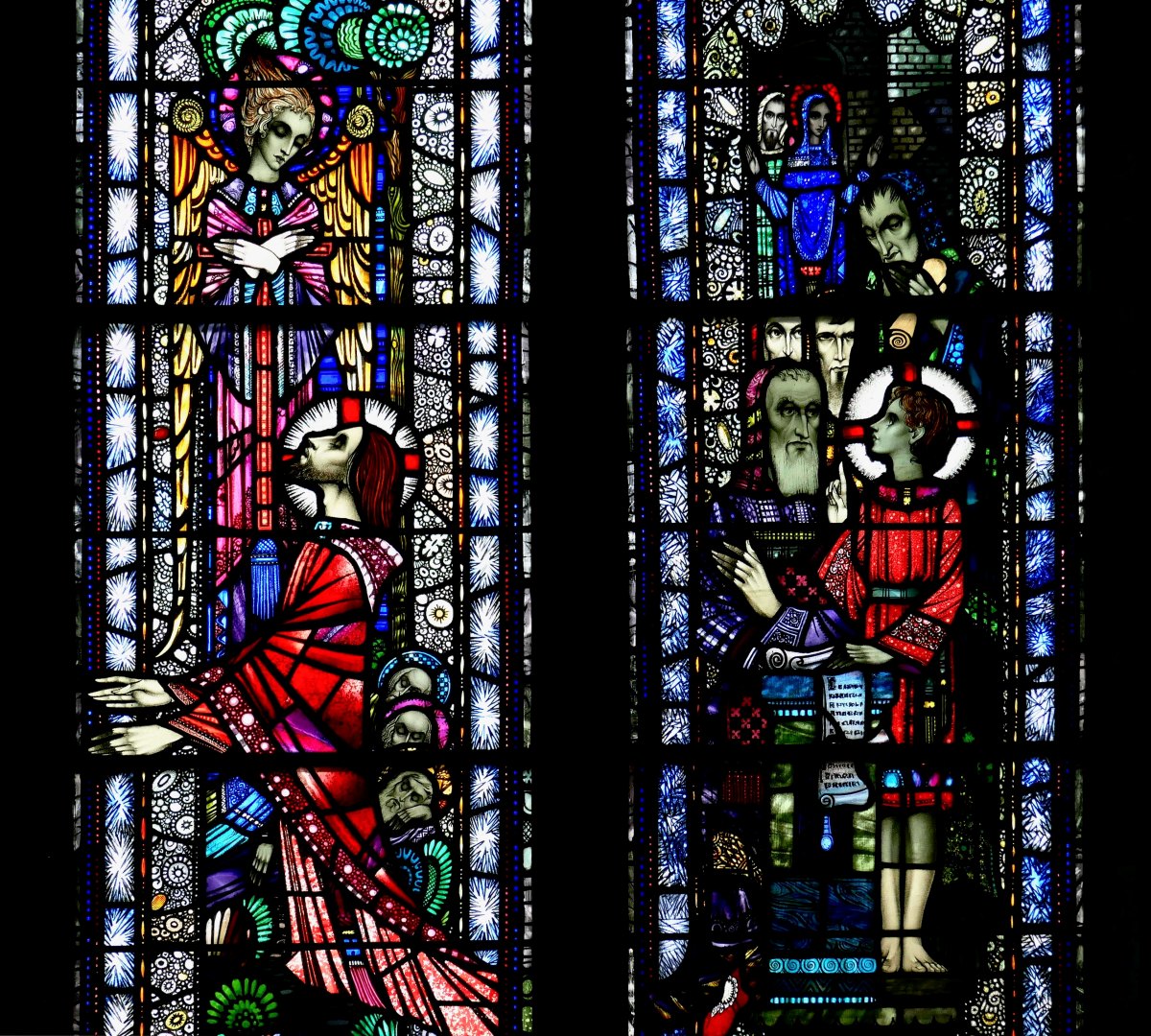

There were two submissions that we know of, and the first was by none other than Evie Hone. We know this because her full-size sketch for the window is displayed on the wall of the Holy Cross Church in Dundrum, having been acquired for the church by Fr Kieran McDermott. I am grateful to David Caron, General Editor of the Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass, and administrator of Irish Stained Glass on Instagram, for the photograph and information. The accompanying text refers to the drawing as a cartoon and states that it was done for the Drogheda Grammar School, but ‘never realised.’ It does indeed look like a cartoon, in that glass cutlines have been included, and is very recognisably in her 1940s style.

The second submission was by the Harry Clarke Studios. The Studio won the commission on the merits of the sketch they submitted, but that bit comes later.

Story 3: Erasmus

The window was duly installed in the chapel in the Drogheda Grammar School, an academic institution originally part of the Erasmus Smith Charter Schools. Erasmus Smith made his money supplying Cromwell’s army. In part payment he was given land in Ireland. After the Restoration, this put him in an awkward position with the Crown and so he

manoeuvred to protect his position and to further his essentially Puritan religious stance, which he modified to suit the religious sensibilities of the new Royalist regime. He achieved this in part by creating an eponymous trust whereby some of his Irish property was used for the purpose of financing the education of children and provided scholarships for the most promising of those to continue their studies at Trinity College, Dublin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus_Smith

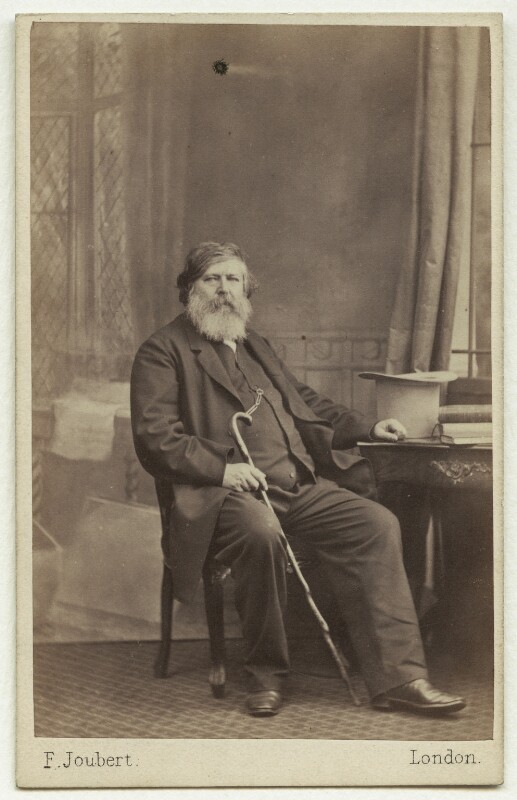

Erasmus Smith By Circle of John Michael Wright Public Domain

One of the schools that was established under the Trust was the Drogheda Grammar School – which is both ironic and fitting, given that Drogheda was one of the towns notoriously devastated by Cromwell.

Story 4: The School

Today, Drogheda Grammar School is a respected non-denominational, co-educational secondary school. It is operated under a management committee and subscribes to a Quaker ethos. Originally a boys’s boarding school, up to 1976 it occupied a prominent place in the town centre, right beside St Lawrence’s Gate, but even by the 1950s was becoming in need of refurbishment.

When it moved out to the present site, the window was put into storage, where it remained until 2012 – out of sight, but not forgotten. A brand new school was completed in 2012 and the window was installed into a Reflection Room.

Story 5: Brittas Bay Antiques

Wait – how did this story manage to wind its way to a quirky antique store by the beach in Wicklow? Well, at some point in the last couple of years Niall (below and yes, he really is that tall) and Chrissie, the proprietors, picked up a box of curios from someone, and discovered a Harry Clarke Studio sketch inside it. They advertised it online and someone stumbled across it, paid for it, and asked me to pick it up for her. I was happy to do so. (The shop is an Aladdin’s Cave, by the way – most enjoyable browsing I have done in years!)

Story 6: Etain

So c’mon Finola – ‘someone’ asked you to pick it up? Who exactly? It was my friend, Etain Clarke Scott, daughter of David Clarke and grand-daughter of Harry Clarke and Margaret Clarke. She and her siblings live in Texas, although they grew up in Dublin and make frequent visits over here. It was on her last visit, with her sister Veronique, that she asked me to pick up the sketch.

This is Etain (left) and Veronique (right) – as you can see they are both beautiful, and lots of fun! (And she will probably kill me from stealing this photo from her Facebook page.)

Story 7: The Research

At this point, we knew that the sketch was a window design produced by the Harry Clarke Studios for the Drogheda Grammar School – it said so right under the sketch, but we didn’t know whether the window had ever been made or whose work it was. The first question was easy – a quick Google led us to the school website and to the story of the window. I suspected that the artist was the Studio’s manager and chief designer, William Dowling, who took over the role from Richard King upon King’s departure in 1940. Regular readers will know by now that long after the death of Harry (in 1931) the Studios had continued with what I have called The House Style since what people wanted was ‘A Harry Clarke’.

I consulted with my stained glass colleagues – David Caron, Paul Donnelly, Jozef Voda and Ruth Sheehy, all contributors to the Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass and all very knowledgeable indeed on the work of the Studios during this period. I offered in evidence a couple of examples of Dowling windows of the same subject – Christ Among The Doctors or The Finding in The Temple. The one above is in Wicklow and the one below in Balbriggan.

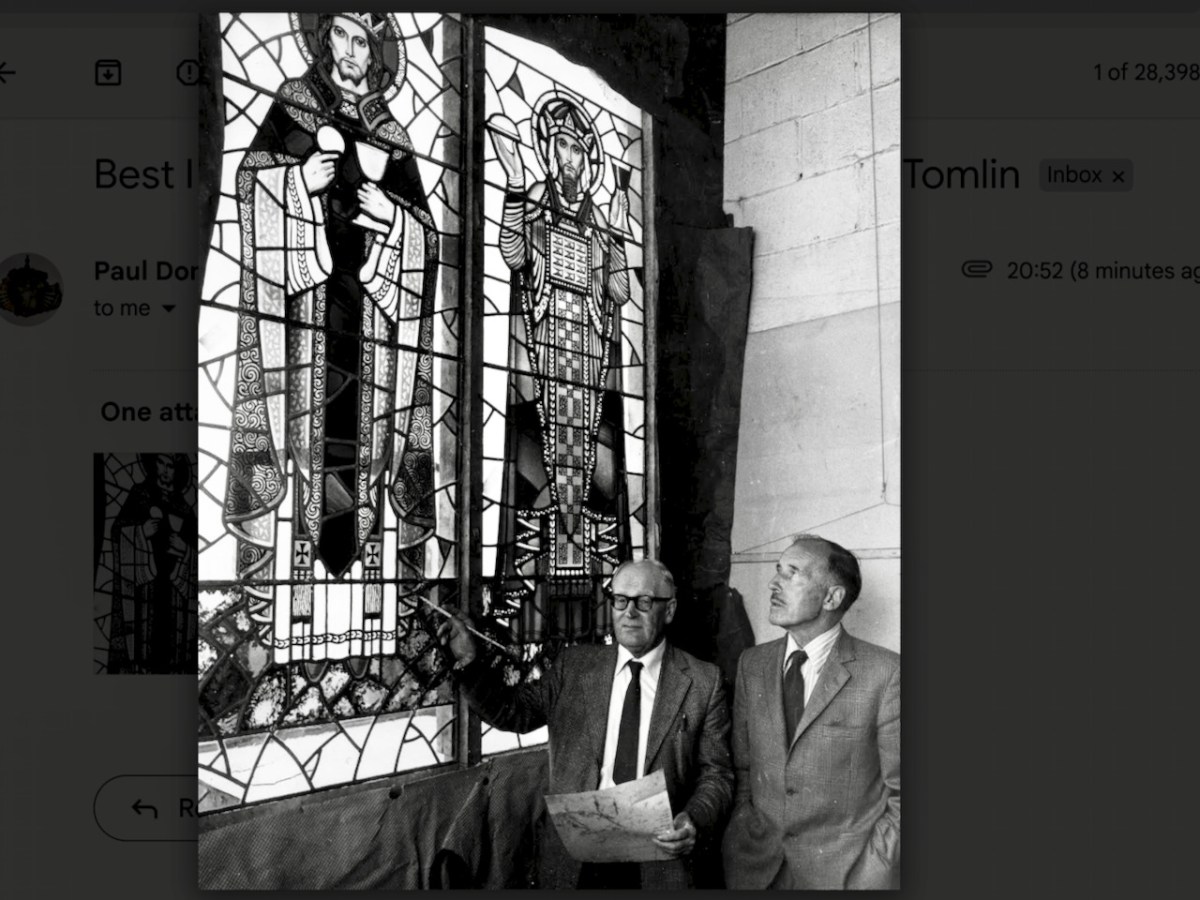

There was much helpful discussion by email: it was at this point David contributed the information and photograph about the Evie Hone cartoon, and both Paul and Ruth identified the handwriting as Dowling’s and agreed that the style was his. Etain remembers Willie Dowling well as a kind and avuncular presence in the studio, always impeccably dressed, and she was pleased at this attribution. That’s Dowling below (left), with Stanley Tomlin, at the Studios at a later date.

Story 8: Taking the Photographs

We had the sketch and now we knew whose work it was and also that it was in situ in the school. What we didn’t know was what the window actually looked like. Was it exactly as the sketch has intended? Had changes been made to the shape or dimensions of the window? This often happens when older windows are inserted into newer openings. I contacted the school and asked for permission to come and photograph the window, which was graciously given.

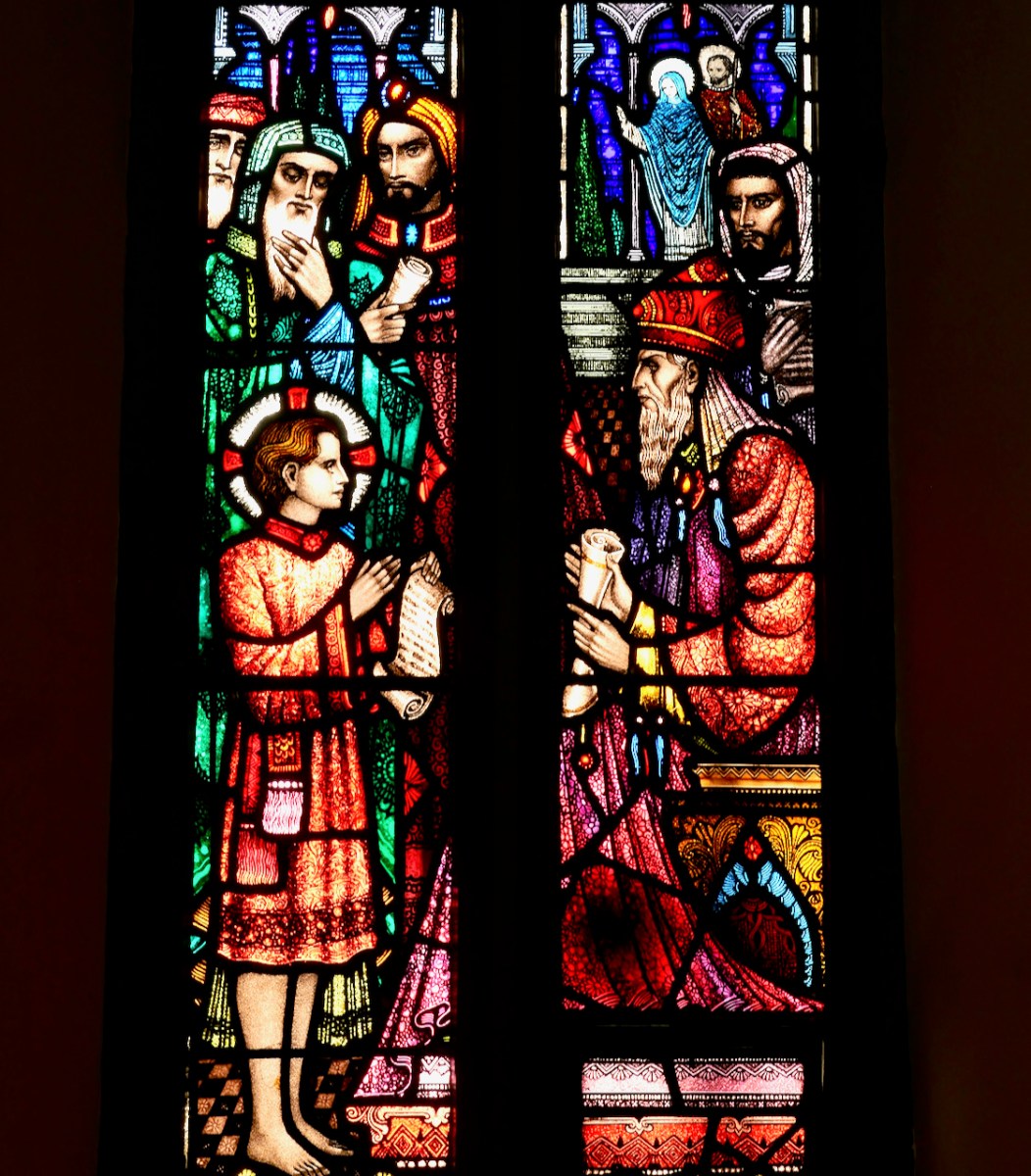

What I found was that the stained glass had been carefully inserted into a larger window, protected front and back with toughened glass, and the story of the Bole Memorial Window was provided in a framed script on the wall. Although Etain’s sketch shows a window with a rounded top, this opening was square. If the window had been changed to fit more recently, it had been done so skilfully that it was not obvious or indeed detectable.

In fact, the window far exceeded my expectations. It is beautiful. Dowling had used good glass and the effect is jewel-like and vibrant. He has gone to town on every panel, painting, aciding, scratching, and filling even the smallest piece with decorative detail.

The figures of the Doctors are expertly rendered, while the small Joseph and Mary are similar to his Balbriggan and Wicklow panels. Jesus looks suitably solemn and earnest, as befits the good model that was intended for the students.

Afterword

Thank you to the Drogheda Grammar School for facilitating the photographic session. It was wonderful to hear, from the school Principal, Hugh Baker, that the window is treasured. Thanks to my collegial group of stained glass scholars for their advice and additional photographs. Most of all, thank you to Etain for entrusting me with the sketch and sending me down this story lane.