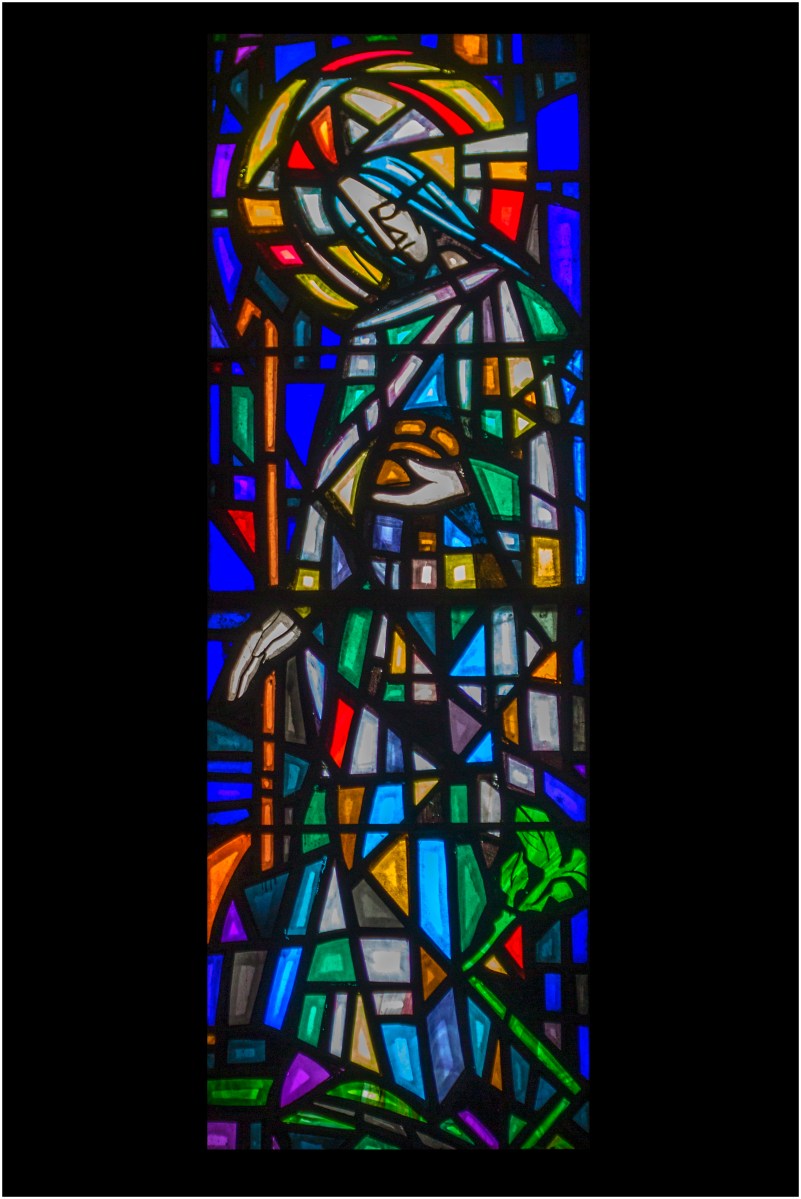

There are several versions of the Brendan story (that’s a Harry Clarke Brendan, above, from Tullamore), and some of the stories in one version might not be present in another. This particular version is told in a series of illustrations, each one captioned in what Biedermann calls “faulty monastic Latin.” It is contained in a much larger work, the Krumauer Bilder-Codex (or Illustrated Codex), and occurs at the end after many other stories of saints. A Codex, by the way, is a book, rather than a scroll. In the 14th century, vellum was used as the main writing material. The drawings are line drawings in pen and ink. They are simple, but in Biedermann’s opinion ‘joyful.’ I agree. Here’s one of the stories.

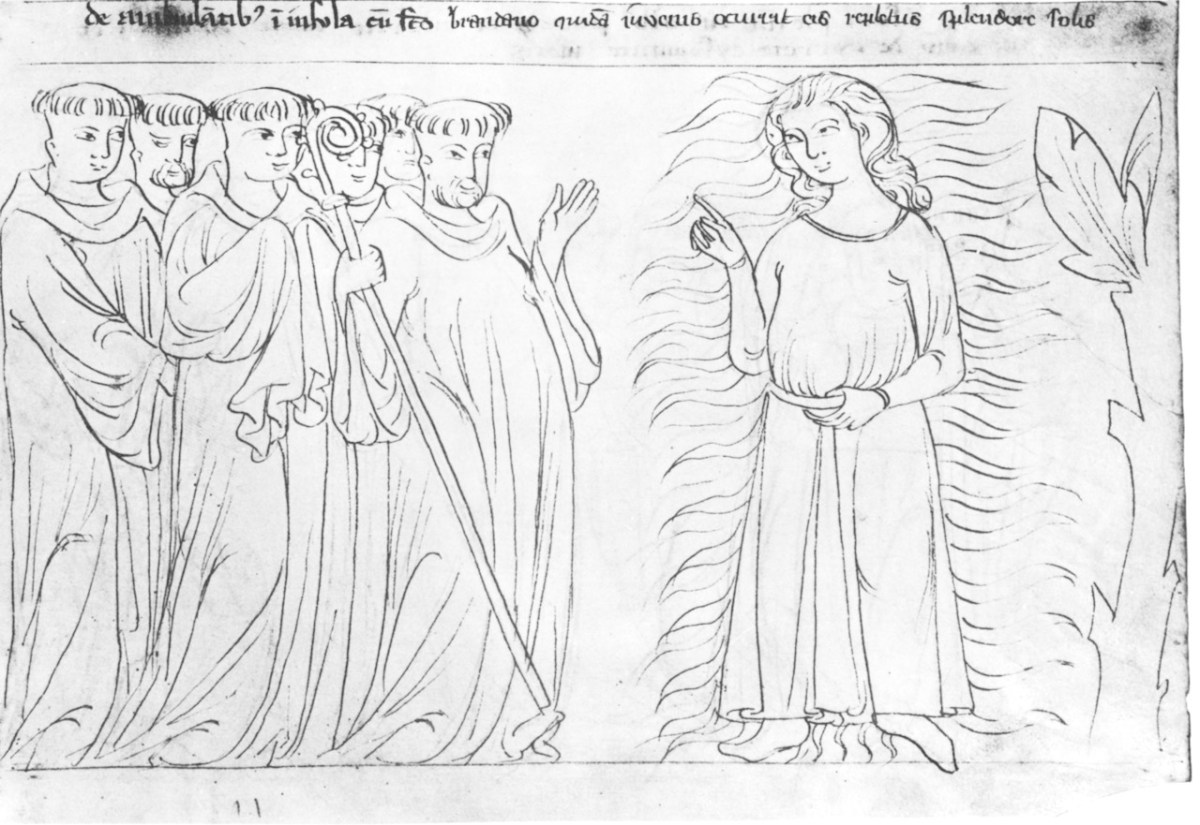

While they were walking on the island with Saint Brendan, a certain young man met them, filled with the radiance of the sun.

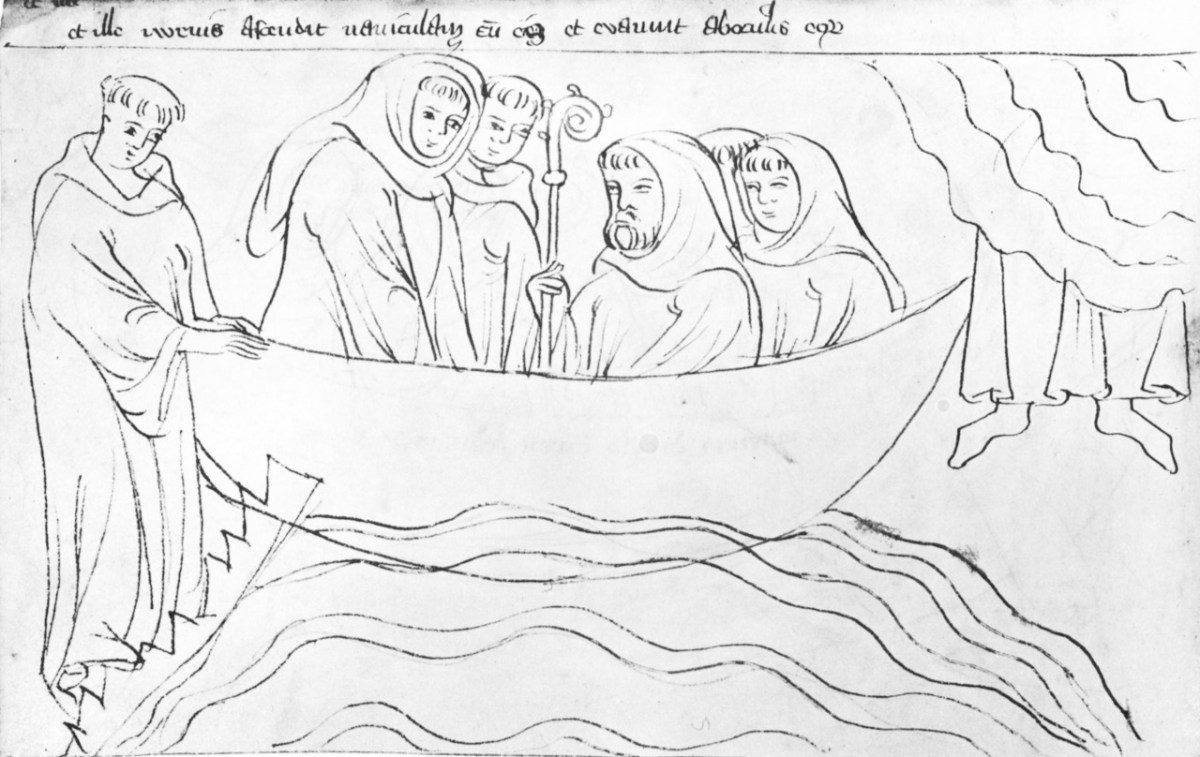

And that young man boarded the little ship with them and vanished from their sight.

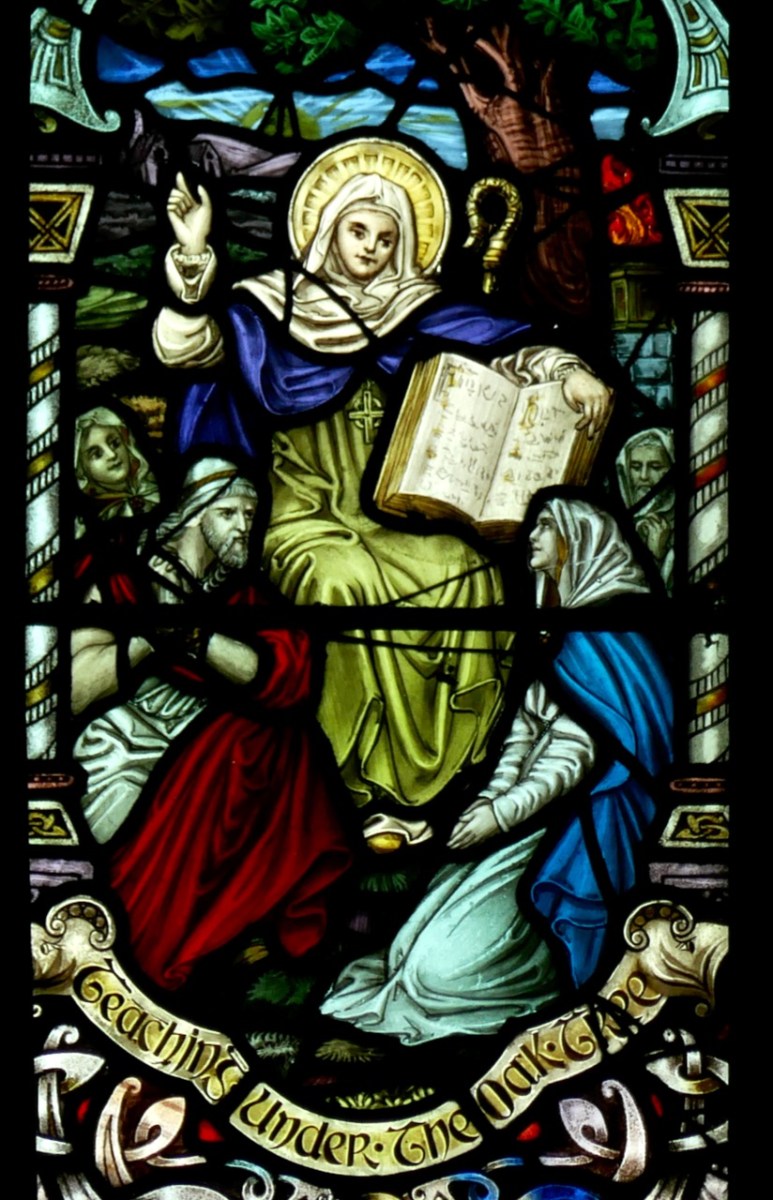

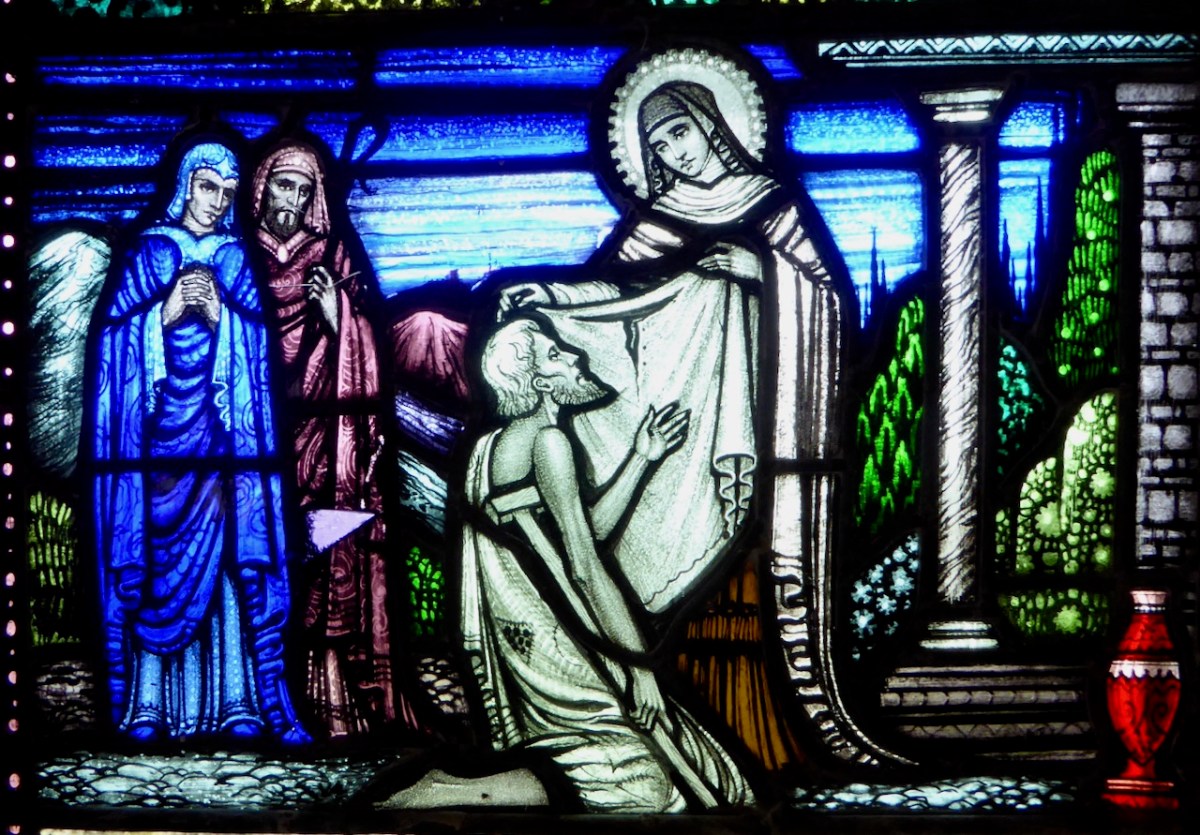

I love the way you see only his legs disappearing up into the clouds. St Brendan, although happy to see the radiant youth in the first illustration, is looking a little grumpy in this one. “What did we do wrong, that he left us”, I can hear him say. You may note, by the way, that in some illustrations the monks are depicted in a curved shape, like Brendan in the first line drawing above. This convention, known as the S-curve, is also seen in medieval stained glass windows, such as this one from the Exeter Museum.

Here’s another one, from St Helen’s Church in York. This S-curve was a way of introducing some sense of movement into a figure of a saint or monk, and was a typically gothic element, perhaps an attempt to make the figure less rigid.

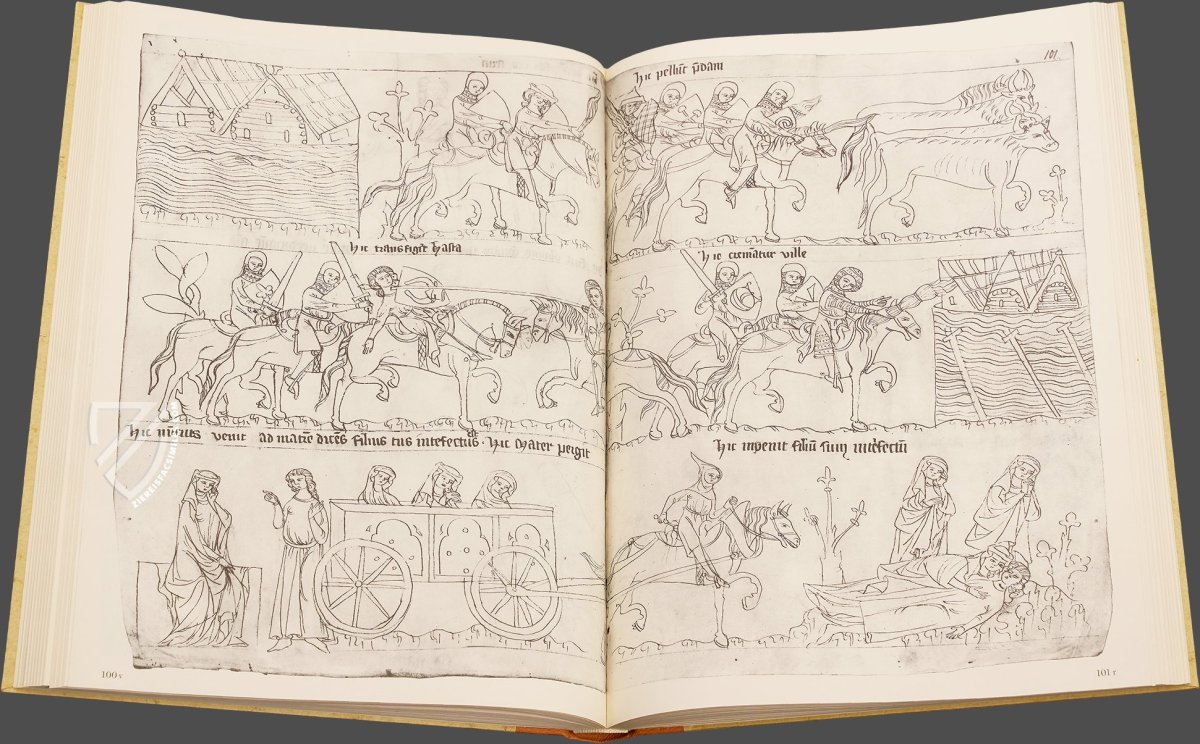

The illustrations are laid out on facing pages, so you read top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right. Although the Brendan story has four illustrations per two-page spread, most of the stories in the Krumauer Bildercodex have six, or occupy three horizontal spaces instead of two. Here’s an image of a typical lay-out, although I don’t know what story is being told in it.

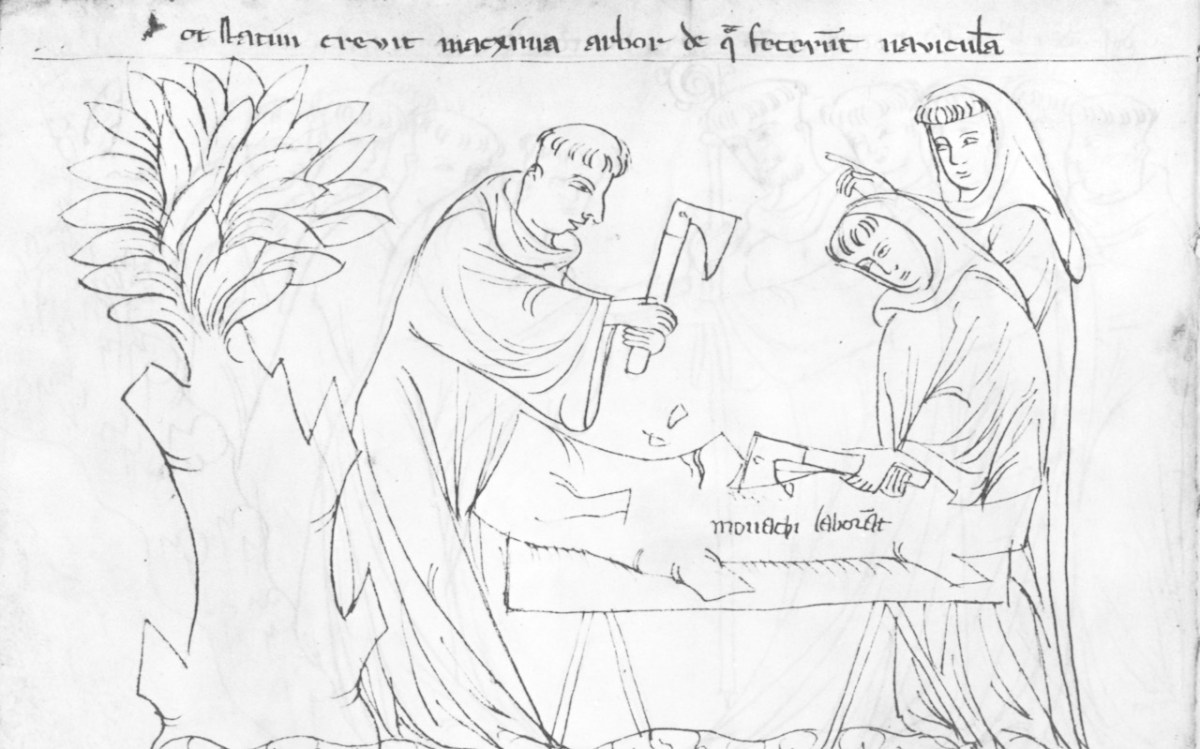

At some point there is a need for a new boat. No problem – Brendan sticks his staff in the ground and immediately a tree springs up. The monks set to work on it and in no time have carved out a boat.

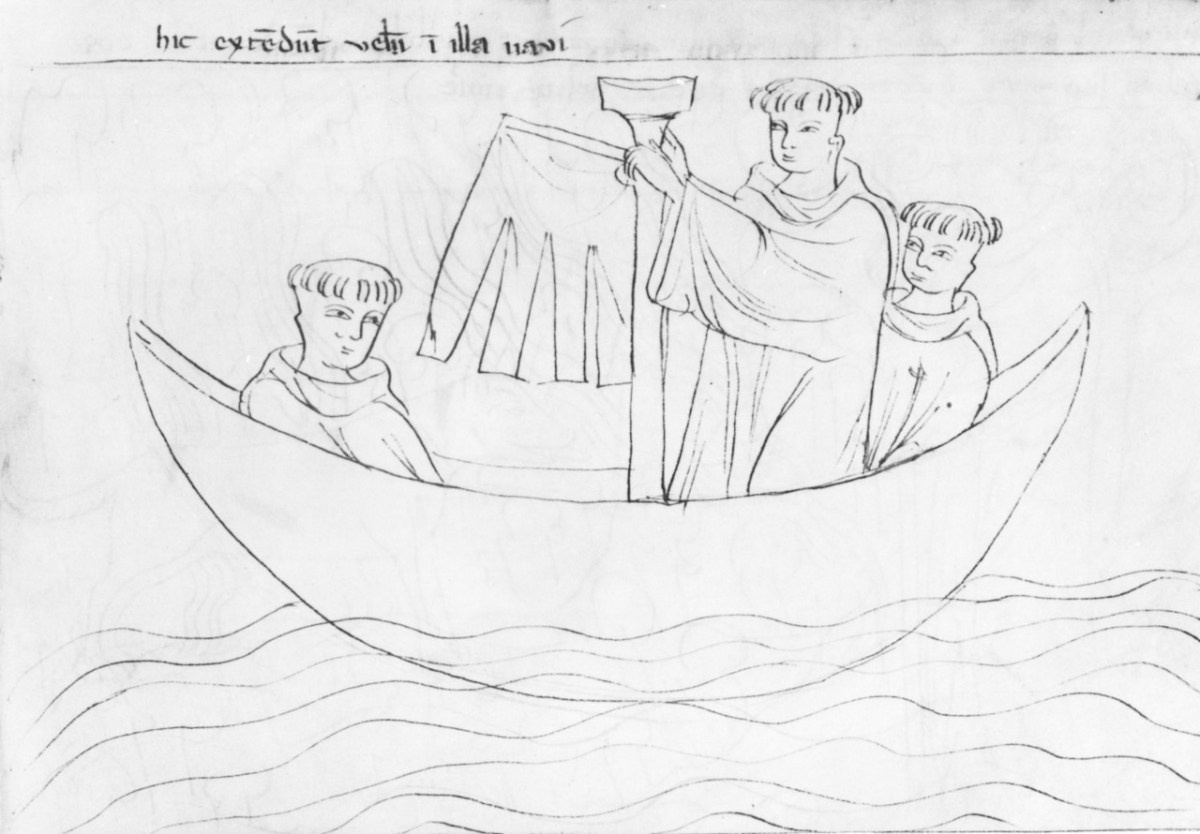

In the next illustration they are at sea and raising a sail. Aha – I hear you cry, but now there are only three of them. And what kind of sail is that? And also – surely they were in an Irish curragh – what about all the hides? Alas – the Codex provides no answers to our urgent questions, although the story-teller who used the illustrations as he narrated to an eager audience may have done all that. We don’t know who commissioned the Krumauer Bildercodex, although since a production like this was time-consuming and expensive, it may have been a noble patron or a monastery.

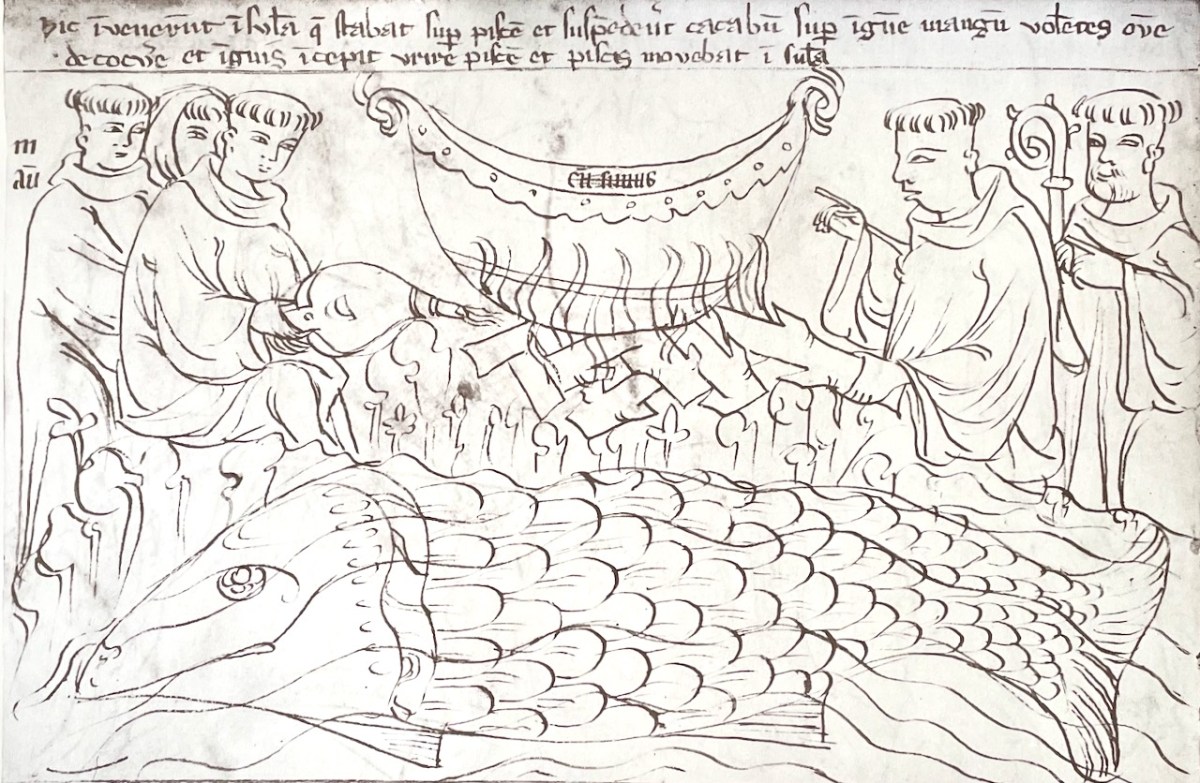

One of the most famous of the Brendan stories is that of the giant fish, sometimes called Jasconius, and often referred to as a whale.

The caption reads: Here they found an island which stood upon a fish, and they hung a pot over a great fire, wanting to boil a sheep, and the fire began to burn the fish, and the fish moved the island.

Here is Whitley Stokes’ translation of the story from the Book of Lismore

Now after the Easter had come the great sea-beast raised his shoulder on high over the storm and over the wave-voice of the sea, so that it was level, firm land, like a field equally smooth, equally high. And they go forth upon that land and there they celebrate the Easter, even one day and two nights.

After they had gone on board their vessels, the whale straightway plunged under the sea. And it was in that wise they used to celebrate the Easter, to the end of seven years, on the back of the whale, as Cundedan said :

Brenainn loved lasting devotion

According to synod and company :

Seven years on the back of the whale :

Hard was the rule of devotion.

For when the Easter of every year was at hand the whale would heave up his back, so that it was dry and solid land.

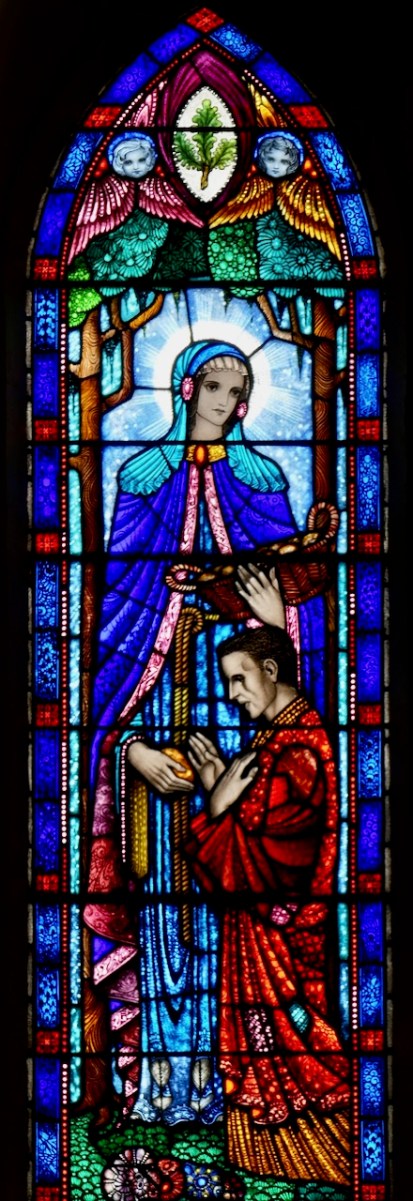

Since this is one of the most celebrated of the Brendan legends, it is not surprising that it is the story we see most often depicted in stained glass windows. Above is a beauty by Ethel Rhind of An Túr Gloine, in St Brendan’s College in Killarney. And of course, below, one by George Walsh, this one from St Brendan’s Church, the Glen, in Cork.

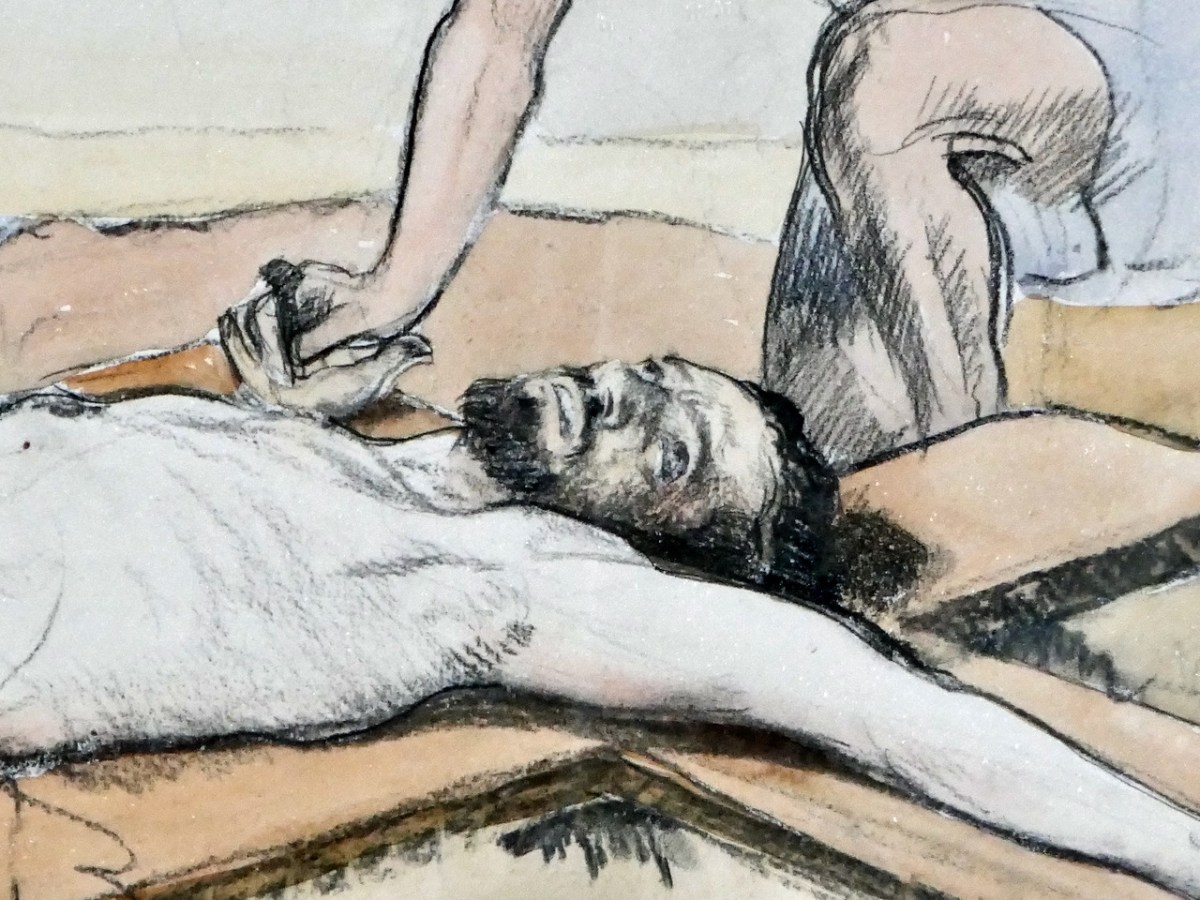

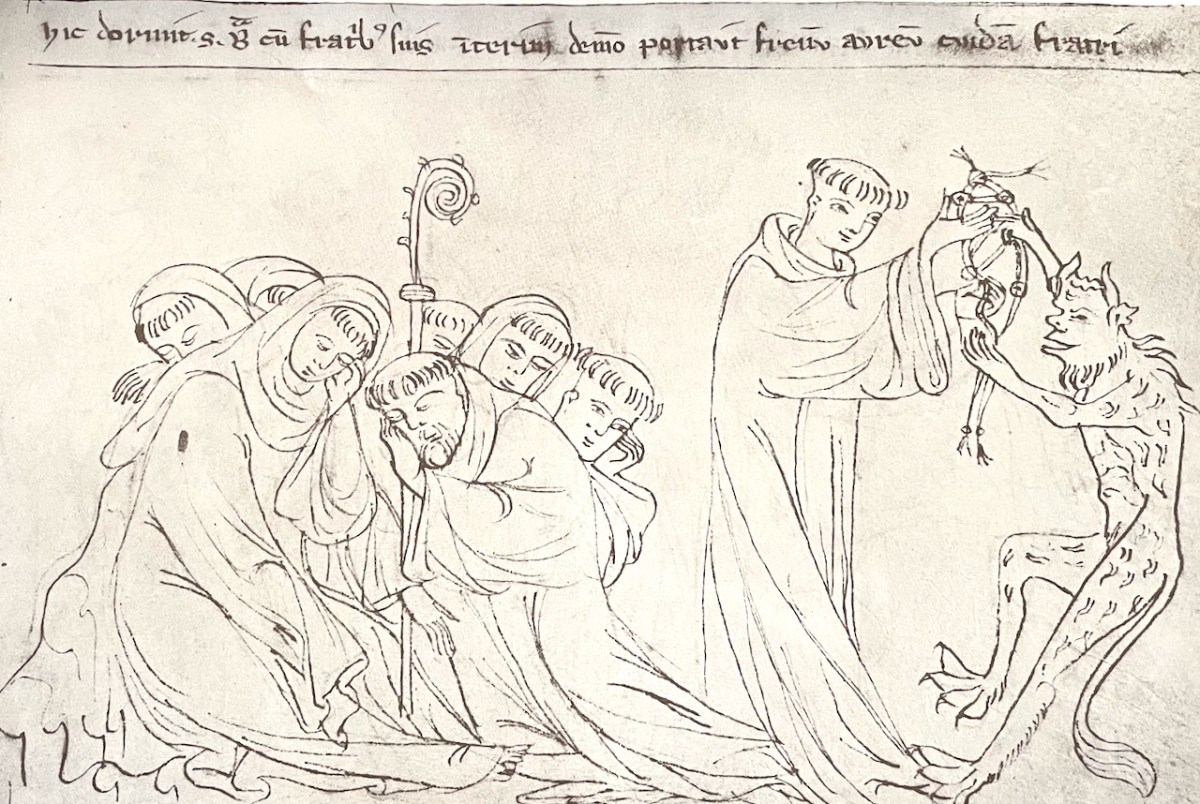

I will conclude this post with five illustrations for the story of the Golden Bridle, called the Silver Bit in the account I am using. This version is from the esteemed Canon O’Hanlon, (below) from his Life of St Brendan, in Volume 5 of his Lives of the Irish Saints (available online at https://archive.org/).

It is obvious, since the illustrations track so closely, that O’Hanlon was using the same translation as the Bilder-Codex. But I should warn you that in his translation the demon is cast in the form of a black child, an ‘Ethiop,’ as it is in other versions too. In the Codex it is simply referred to as a demon and depicted as a horned beast with a tail.

But, while they slept, Brendan saw a child, black as an Ethiop, holding a bit, and playing before the unfortunate brother, in whose eyes he made it glitter. The saint arose, and he passed that night in prayer till day. When morning dawned, the monks rose as usual, to give praise to the Almighty, and afterwards to regain their ship. Once more, the table was found furnished, as on the day preceding; and thus, for three days and for three nights, the Lord prepared food for his servants. There, too, for three whole days, by the Divine will, they rested on that isle.

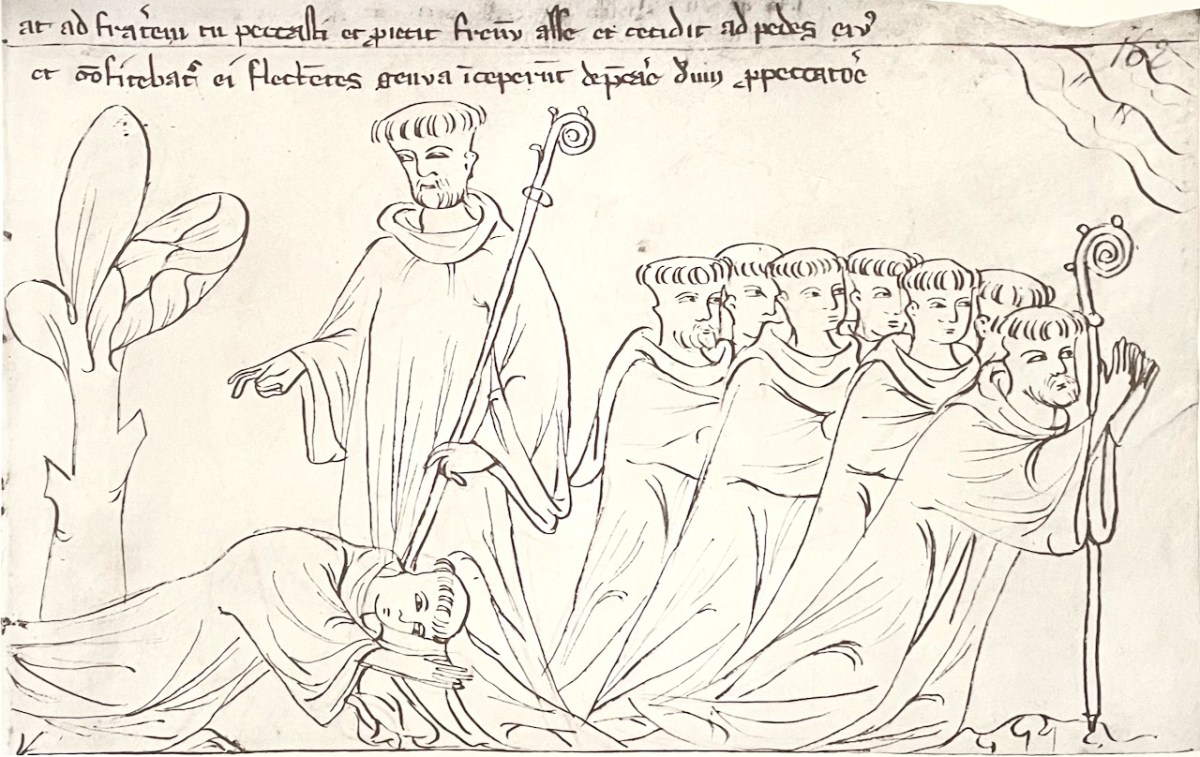

Then they returned to their ship, when Brendan said: ” See, brethren, doth not one of you carry off something from here?” “God forbid,” they replied, “that a robbery should dishonour our voyage.” “Then,” said St. Brendan, “behold, our brother, whom I warned yestereve, has now in his robe a silver bit, that the devil gave him this night.” The brother instantly flung that bit en the ground. . .

. . . and fell at the feet of the man of God, crying: “Father, I have sinned: pardon! pray for the salvation of my soul.” And, at the same moment, all fell down to pray for their brother’s salvation.

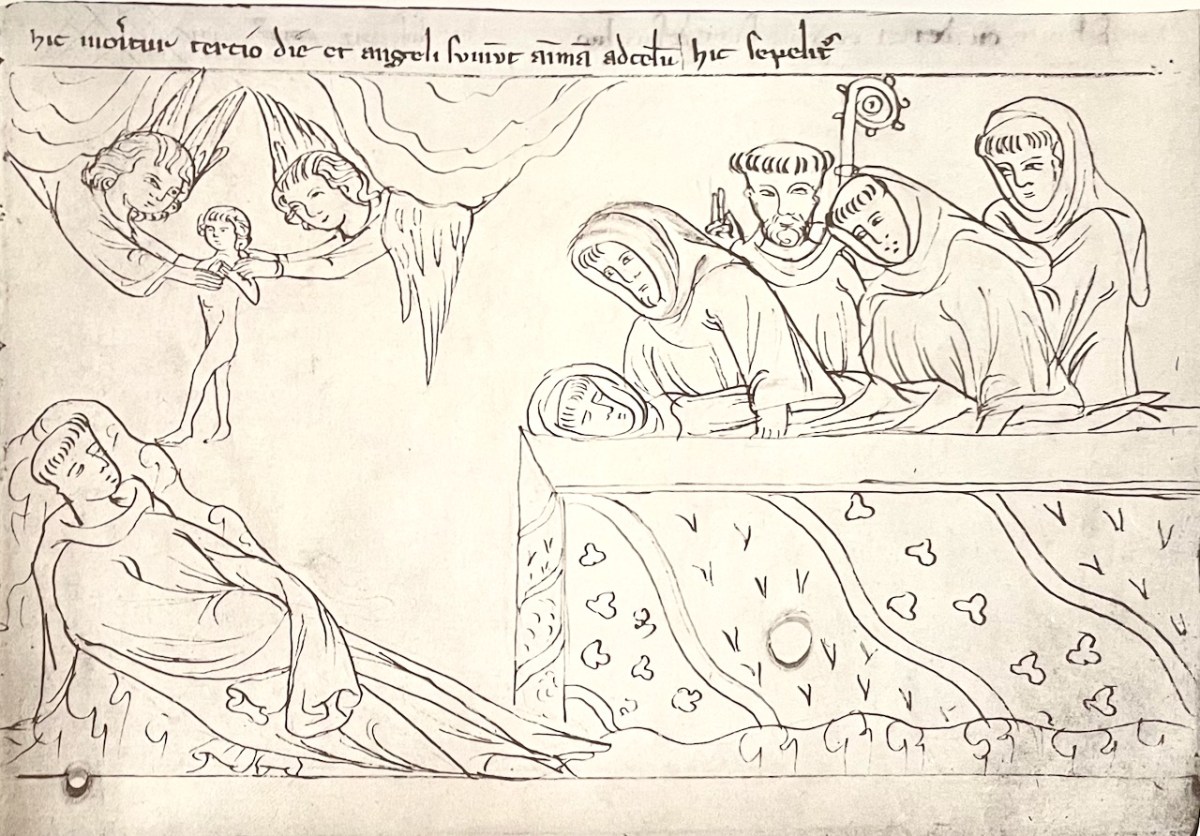

Rising up, they saw the wretched Ethiop escape from the guilty man’s bosom, howling and crying : “Why drive me, O man of God, from my abode, where for seven years I have dwelt, and thus expel me from my inheritance. Brendan immediately turned to the brother, and said: “Receive promptly the Body and Blood of Christ, for thy soul is about t leave thy body, and this is the place of thy burial. But, thy brother, who came with you from the monastery, shall find his place of sepulture in hell.” Whereupon, that penitent monk received Holy Eucharist . . .

. . . and his soul departed; but, it was received by Angels, in the sight of the other monks. His body was then buried. Also, St. Brendan had ordered the expulsed demon, in God’s name, to hurt no person, until the Day of General Judgment.

There’s more of course, and I am undecided whether to continue next time or come back to it later. I’ll sleep on it, and dream of the Land of Promise and of picnicking on the back of a whale.