I spent Saturday in Baltimore celebrating, with dozens of Crowleys, a signal occasion. This celebration involved the iconic boat The Saoirse, exhaustive genealogical research, long lost cousins meeting for the first time in over 300 years, and a remembrance of a devastating episode in Irish History – the Flight of the Earls.

Let’s start with the Flight of the Earls. The Battle of Kinsale in 1601, was the moment that marked the end of the power of the great Irish families and the end of the Gaelic way of life. Many heads of those families who had fought at the battle fled Ireland from Rathmullen in Donegal, heading for the continent, in 1607. Their names can be found in the lists of those who fought in the armies of Spain, France and the Austrian Empire, as well as, sometimes lightly disguised, as landowners, wine-growers and grandees in those countries.

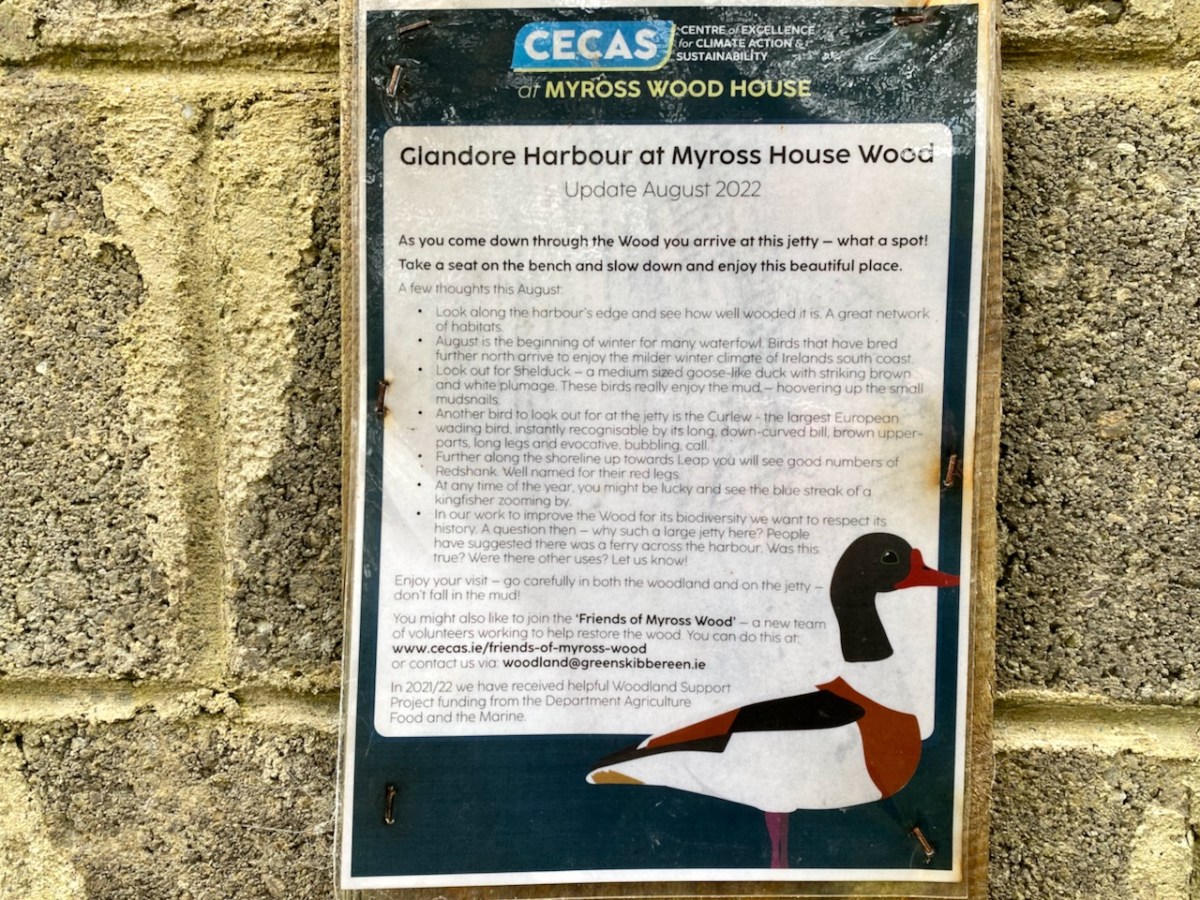

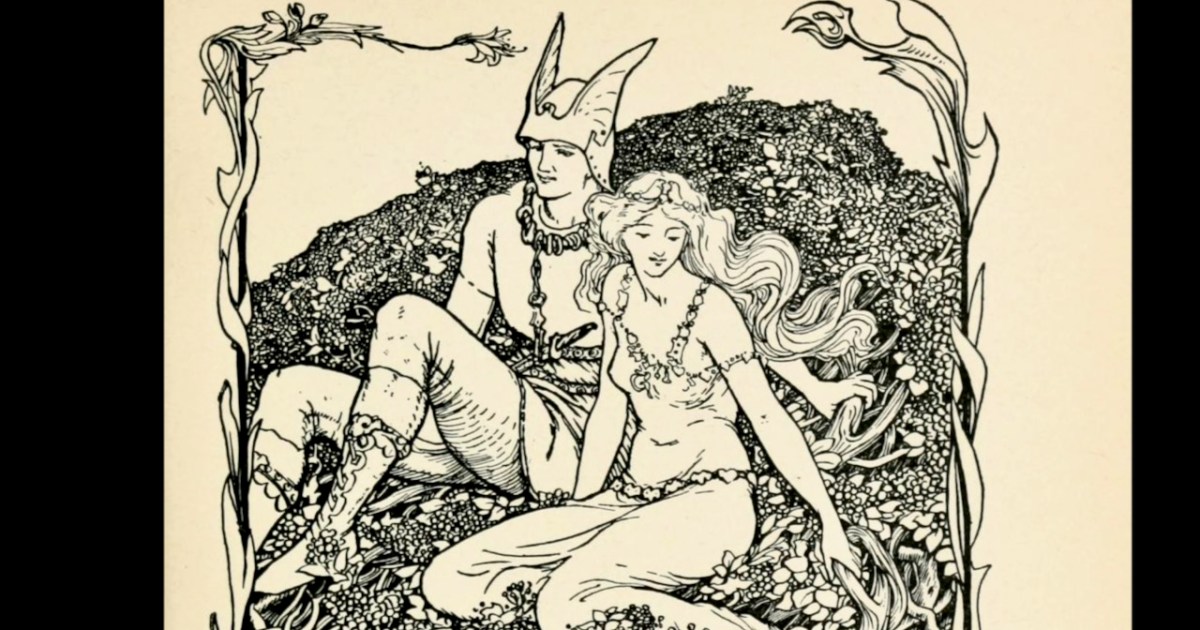

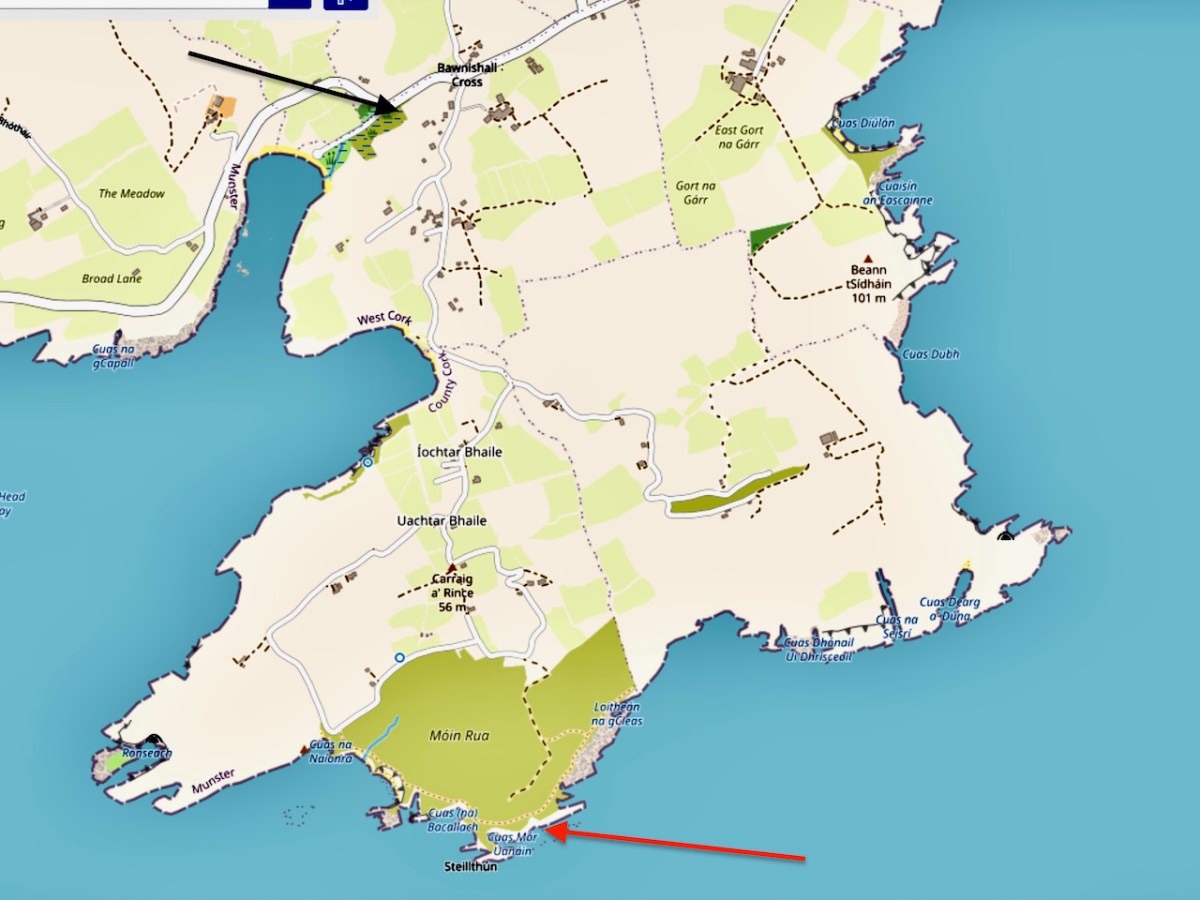

However, one of the leaders, Red Hugh O’Donnell of Donegal, set out earlier, on January 6th, 1602, and he sailed from nearby Castlehaven (below). You can find the whole story, told in a highly entertaining way, on the website of our old friend Gormú. That’s Richard King‘s rendition of Red Hugh, above, being offered a poison cup by a traitor, causing him to die in Spain (where his grave has recently been identified). My lead photograph is his statue, by Maurice Harron, in Donegal town and the cartoon is by John Dooley Reigh, from The Nation (I think). We in West Cork have never forgotten that this is a West Cork story and we feel we can claim Red Hugh as one of our own. This connects us in a special way to the whole saga of the Flight of the Earls.

That flight did not stop in 1607 – Irish men and women, clan chieftains, soldiers and peasants alike, continued to leave for the continent over the next centuries.

Among those who left were the parents of Don Pedro Alonso O’Crouley. Here are the details from the Crowley Clan website:

Pedro Alonso O’Crouley was born in Cadiz in 1740. Both his parents had emigrated from Ireland. His father Dermetrio (Diarmuid or Jeremiah) was from Limerick claiming descent from Cormac O’Crowley born in Carbery, Co. Cork in 1550. His mother was an O’Donnell from Bally Murphy in Co. Clare.

At nine years old he was sent to France where he got a classical education from the Augustinians at Senlis. He chose to follow a career as a merchant and got a licence for Veracruz and made his first journey to Mexico at the age of 24. Over the next ten years he repeated the journey several times and built up a large fortune from his trading business.

While in Mexico, or “New Spain” as it was called, he gathered every bit of information he could about the country and its history, geology, vegetation, animals, etc. and wrote up his findings in the “Idea compendiosa” – A description of the Kingdom of New Spain” in 1774.

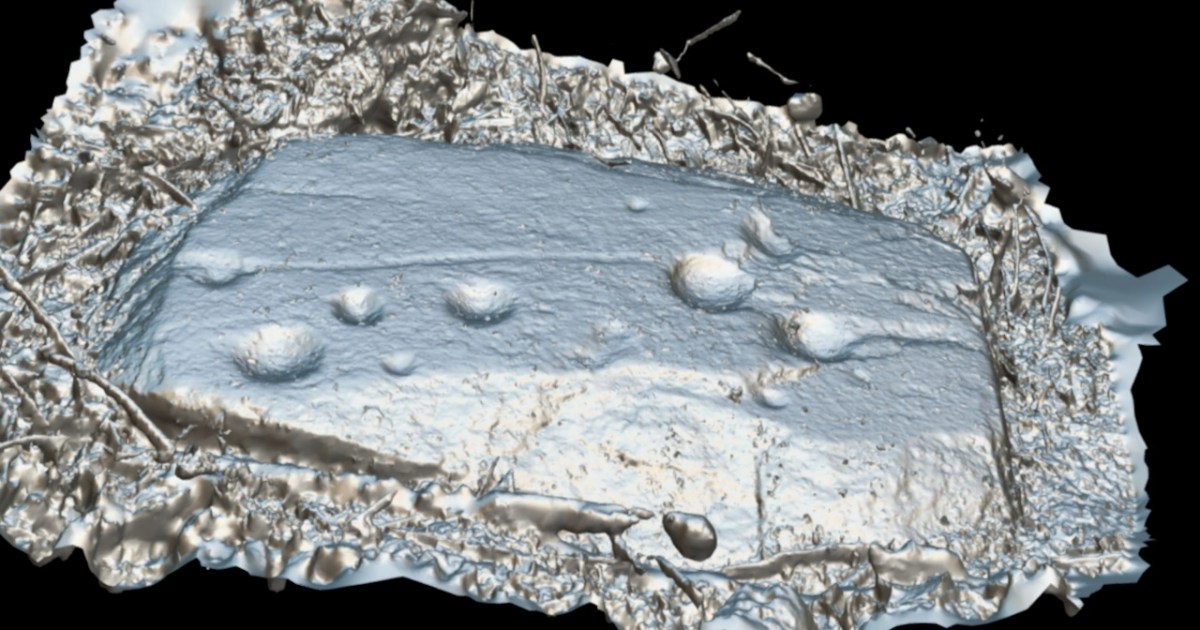

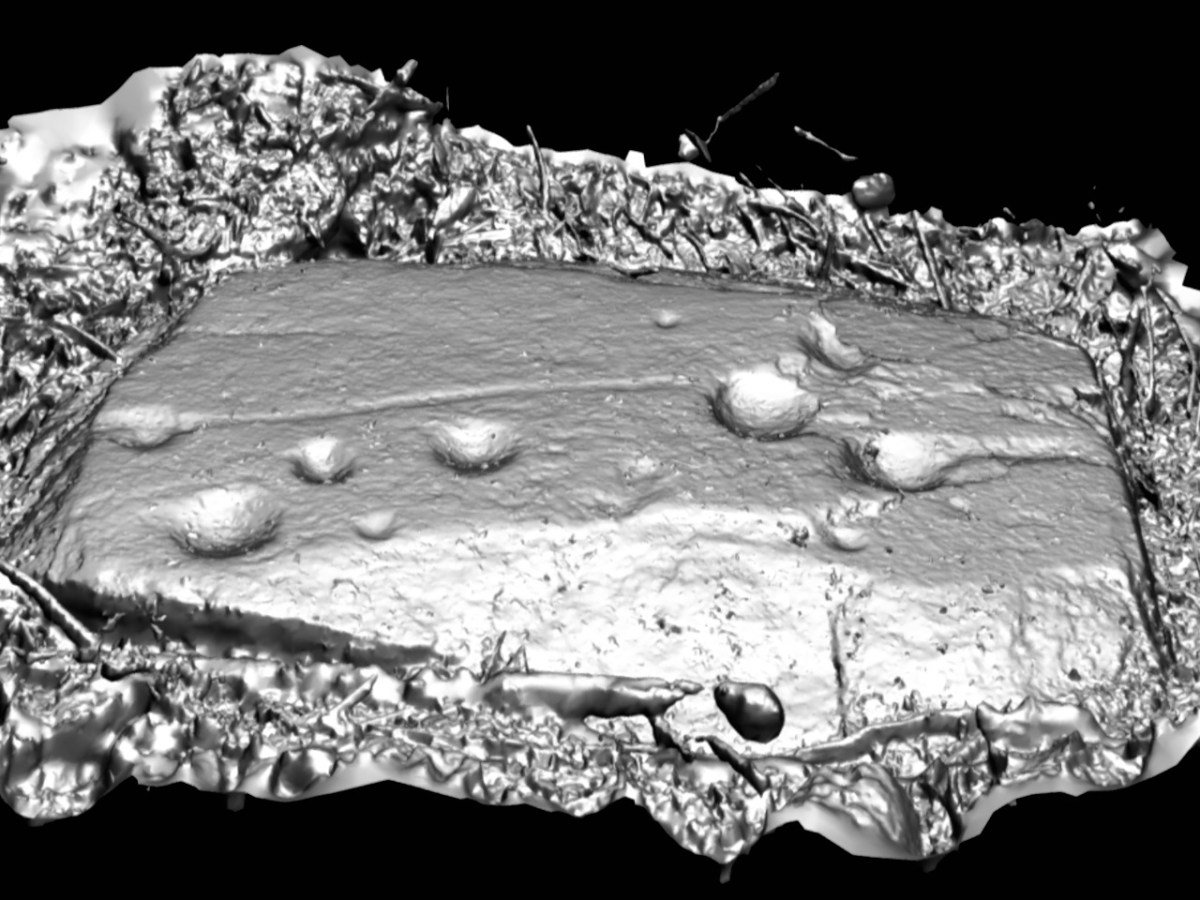

After returning from Mexico O’Crowley stayed on in Cadiz pursuing his interests in antiquities and history. In 1794 he published a catalogue of his private collections called “Musaei o’croulanei”. It lists over 5,000 Greek and Roman coins and 200 paintings including works by Van Dyck, Rubens, Murillo, Velaquez, Zurbaran and Ribera. He also had many geological specimens he had gathered in New Spain.

Pedro remains very famous in Cadiz, where his house functions as a museum. And – there are descendants! In 2014 the Crowley website received a letter:

My name is José María Millán Fuentes, and I am a descendant of O’Crowley. I live in Cádiz, Spain, and I am doing work for the University of Málaga on my ancestors. I speak very badly English, but I have a lot of interest in the topic. I would like to help you, and that you also should help me. I have read in your web Antonio Castro, and also I descend from Pedro Alonso O’Crowley O’Donell and Adelaida Riquelme O’Crowley. I have a lot information about the family up to Pedro Alonso, but then everything fades away.

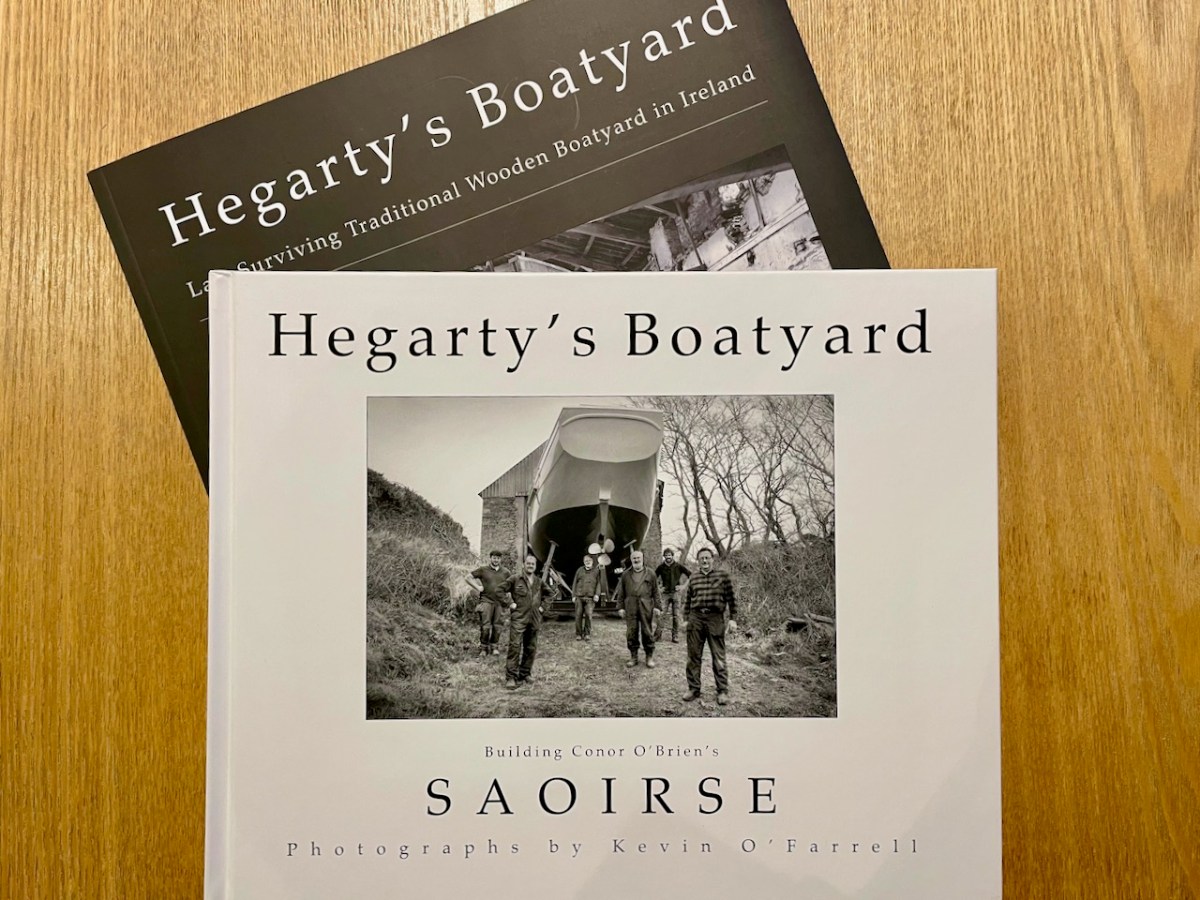

Eleven years later, José Maria is to be the guest of honour at the Crowley clan gathering. The committee discusses how best to make the most of this moment and comes up with a genius idea. He should arrive by sea, born into Baltimore on the iconic boat, the Saoirse. Read about the Saoirse here, and for true traditional wooden boat enthusiasts, you can buy Kevin O”Farrell’s brilliantly photographed book on its reconstruction in Hegarty’s boatyard.

The Saoirse is a big, gaff-rigged yacht, the original version of which was built to sail around the world. It requires a great deal of skill to sail, and thus the task was entrusted to Liam Hegarty.

A flotilla of traditional wooden boats was to accompany her into the harbour but high winds scuppered that plan so in the end only two boats made up the guard of honour – Cormac Levis’s Saoirse Muireann (above) and Nigel Towse’s Honorah.

It was thrilling to see the Saoirse round the Beacon point and tack into Baltimore. I stood with a large contingent of Crowleys, waving flags and cheering, while a group of lively dancers set all our toes tapping.

The most moving moment was when José María climbed up the ladder to the pier, to be met with his 7th cousin, Kevin Crowley from Martinstown, Co Limerick, and enfolded in a welcoming embrace. The Clan Taoiseach, Larry Crowley gave a short, perfect speech. He said, and I paraphrase – José María, your ancestors fled Ireland 300 years ago. They were escaping from oppression, from poverty, from dispossession and from the consequences of resistance. But here we are now, all of us proud Europeans, standing shoulder to shoulder.

Led by a piper, we marched up to the village square.

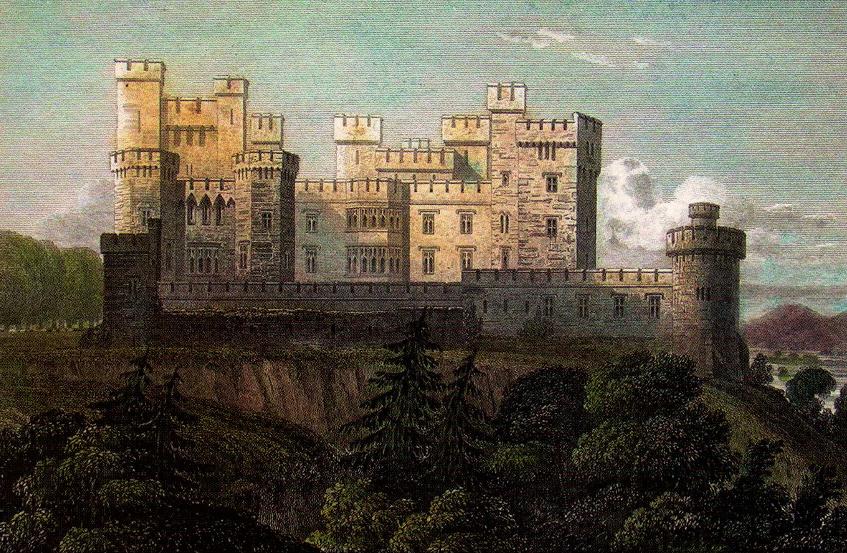

I was struck by the aptness of the Spanish flags passing under the walls of Baltimore Castle – a castle that, in its day serviced the vast Spanish fishing fleets that came for the pilchards and herring. The O’Driscolls became fabulously wealthy through that commerce, and forged alliances with the Spanish that came back to bite them in later years.

There were more speeches, including a masterful summing up of Baltimore’s history by William Casey, and then a squall had us running for cover. The Algiers Inn and other eateries in Baltimore served up a smashing array of sandwiches and soup. I chatted with New Zealand Crowleys and American Crowleys and Irish Crowleys – we all agreed that it had been a perfect Welcome Home.

I may not have all the details exactly right – corrections welcome from knowledgeable Crowleys. My special thanks to Charlie Crowley for inviting me along.