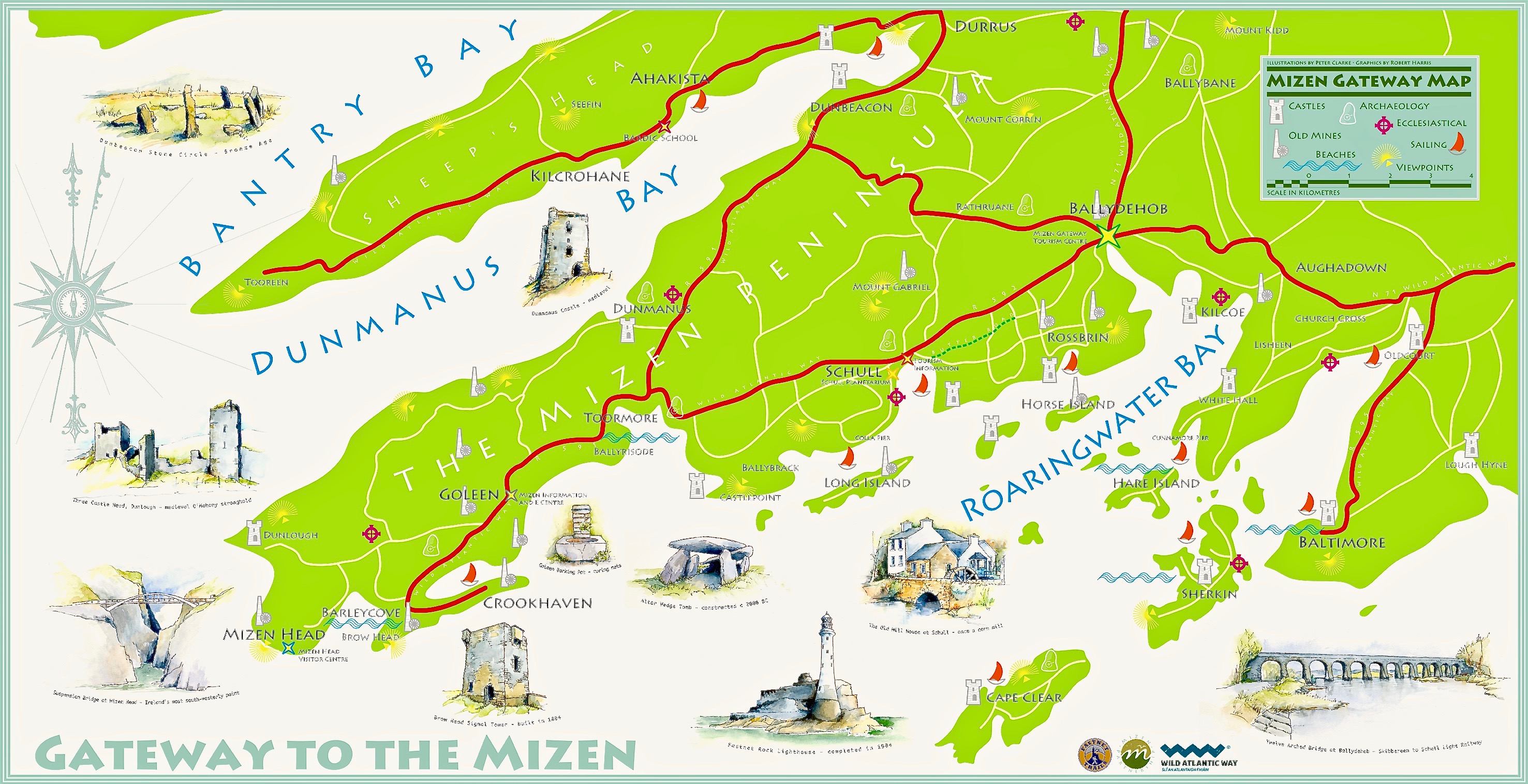

We had, unknowingly, driven past this wedge tomb many times. It’s located on rising ground overlooking the Barley Cove wetlands, in the townland of Ballyvogebeg. The townland name (according to logainm.ie) translates as the Little Place of the O’Buadhaighs, a very scattered clan sometimes translated as Bogue, or Bowe.

The wedge tomb here was formally recorded by archaeologists de Valera and Ó Nualláin in their Survey of the Megalithic Tombs of Ireland in the early 1980s. They provided the scale drawing, below.

It was next surveyed by the Cork Archaeological Survey Team in the early 90s. Oddly, neither of these reports contain any reference to one of the most striking aspect of this megalithic tomb – the cupmarks on the capstones.

The next person to record it was Jack Roberts for his Antiquities of West Cork series, and his drawing clearly shows the cupmarks.

If you are new to this series on Mizen Megaliths, or to megaliths in general, you can catch up with a quick read of my post Wedge Tombs: Last of the Megaliths. This wedge tomb, Ballyvogebeg, fits the pattern, although its ruinous state doesn’t allow us to observe much detail. The side stones have collapsed under the weight of the two large capstones, although you can still see them underneath, leaning at a perilous angle.

De Valera and Ó Nualláin noted that there was no indication of a surrounding mound, which seems to be typical of West Cork wedge tombs. It likely dates to the Copper or Bronze Age, making it around 4,000 years old.

Cupmarks are normally found on open air rocks and boulders, not associated with any monuments and are the most frequent element or motif in Rock Art. However, they are found occasionally on Wedge Tombs and Boulder Burials, so while their occurrence on the Ballyvogebeg wedge tombs is uncommon, it is by no means unique. Intriguing, though! If the tomb had been covered by a mound, they would not have been visible, leading to the conclusion that it was the act of carving them that was important.

Like all of our West Cork wedges, it is oriented towards the west and the setting sun – that is the ‘entrance’ or tallest and widest end, faces the west. The most striking feature of the view is the pyramid-shaped Mizen Peak. What gives the Mizen Peak its distinctive point is a small cairn on its summit.

I haven’t yet been up to this cairn, although I am hoping to get there one of these days. So I am relying on the generosity of our friend Michael Mitchell, of the Walking to the Stones Facebook Page, for the photograph below. Like us, he has been struck by the fact that Mizen Peak seems to be visible from many sites, saying, It’s obviously a very important hill. It seems to be a focus for various megaliths, even some that are not on the Mizen peninsula itself. Michael points out that the cairn does not have the appearance of being ancient but more like a marker cairn.

Curiouser and curiouser, because there is very ancient folklore indeed about this cairn, which, in fact, gives its Irish name to Mizen Head – Carn Uí Néid, or the The Cairn of the Grandson of Néid. Which grandson are we talking about here? Néid had a son, Elathen, who in turn had five sons – the Daghda, Oghma, Bres, Alloth and Delbaeth – all of them figure prominently in Irish Mythology as members of the Thuatha Dé Danann.

Bres is the grandson in question, but Bres was his nickname. He was really Eochaid bres – that is Eochaid the Handsome, because everything comely and handsome that is seen in Ireland, ’tis to Bres it is likened. I am getting my information here from a piece written by J. F. L. in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society of 1912 (available online).

The Dinnshenchas of Carn Uí Néid has been translated by Dr Whitley Stokes

Bres, son of Elathan, died there; ’tis he that in the reign of Nechtan Fairhand. . .King of Munster, demanded from every rooftree in Ireland a hundred men’s drink of a hornless dun cow, or of the milk of a cow of some other single colour. So Munster kine were singed by Nechtan with a fire of fern, and then they were smeared with a porridge of the ashes of flaxseed, so that they became dark brown. . . And they also formed three hundred cows of wood, with dark brown pails on their forks in lieu of the udders. These pails were dipped in bog stuff. Then Bres came to inspect the manner of these cattle, and so that they might be milked in his presence . . . All the bog stuff they had was squeezed out as if it was milk. The Irish were under a geis to come thither at the same time, and Bres was under a geis to drink what should be milked there. So three hundred bucketsful of red bog stuff are milked for him and he drinks it all.

JCHAS Notes and Queries Carn Uí Néid, by J. F. L.

1912, Vol 18, 96, Ps 211-213

Of course it’s a huge and unreliable leap from mythology to a wedge tomb, but I can’t help thinking how great it would be if the Ballyvoguebeg wedge tomb was indeed the tomb of Bres, brother of the Daghda, handsome King of Munster, dead from a surfeit of bog stuff.