This week I was fortunate to be taken on a trip to the Goat Islands – Goat Island and Goat Island Little – by my friend Nicky – thank you, Nicky! We had a fine forecast for the morning and seized our chance.

I can see the Goat Islands from my house and have been wanting to view them up close for as long as I’ve lived here. That’s because the two islands are separated by a cleft and twice a year the sun sets directly in the gorge created by that cleft. I’ve never managed to capture that moment (darn clouds) but I have come close. And somehow that impossibly romantic image, like a corridor to some magical realm, has sunk into my consciousness and manifested as a longing to go through that gorge in person. The experience was just as wonderful as I thought it would be.

There isn’t much history to the Goat Islands. They are unoccupied now except for a herd of feral goats, but there is a small hut on Goat Island, recently re-roofed (does anyone know who has done this and why?).

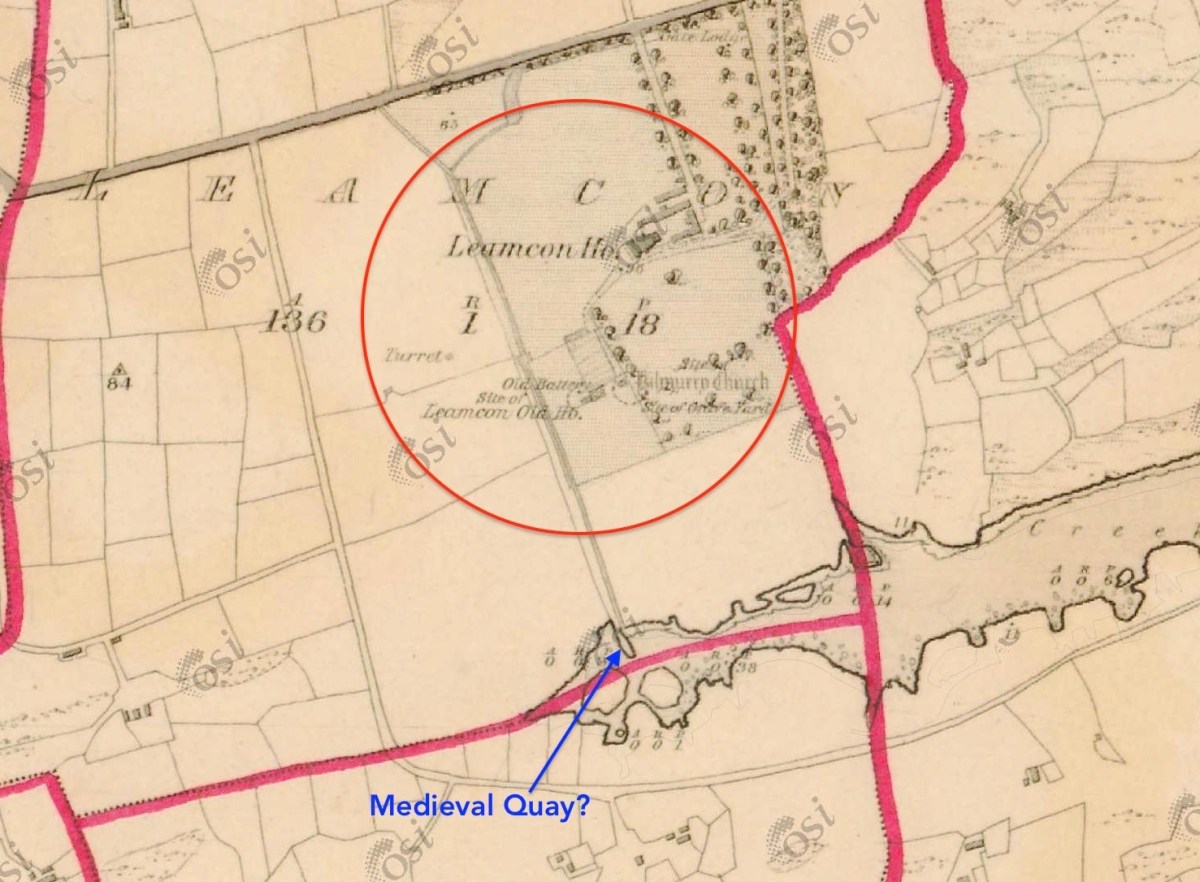

When the first Ordnance Survey was done in the 1840s there was a cluster of buildings – probably the hut and a couple of outbuildings.

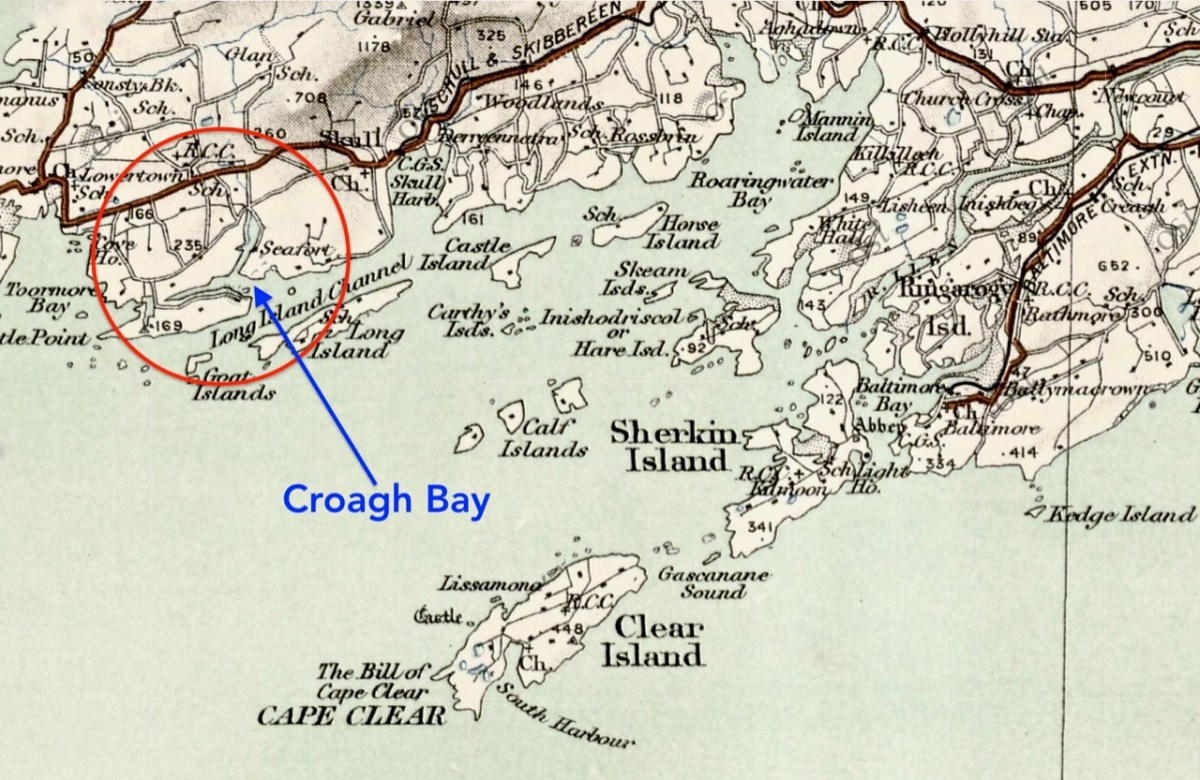

The name in Irish is Oileán Clutharach, which means Sheltered Island. Hmmmm – anything less sheltered is hard to imagine. On some maps and charts, the gap between Goat and Long Island is called Goat Sound, while the gap between Goat Island and the small rocky islet to the west is called Man-of-War Sound. That’s the 1849 Admiralty Chart below. I happen to have a copy, but you can find it here.

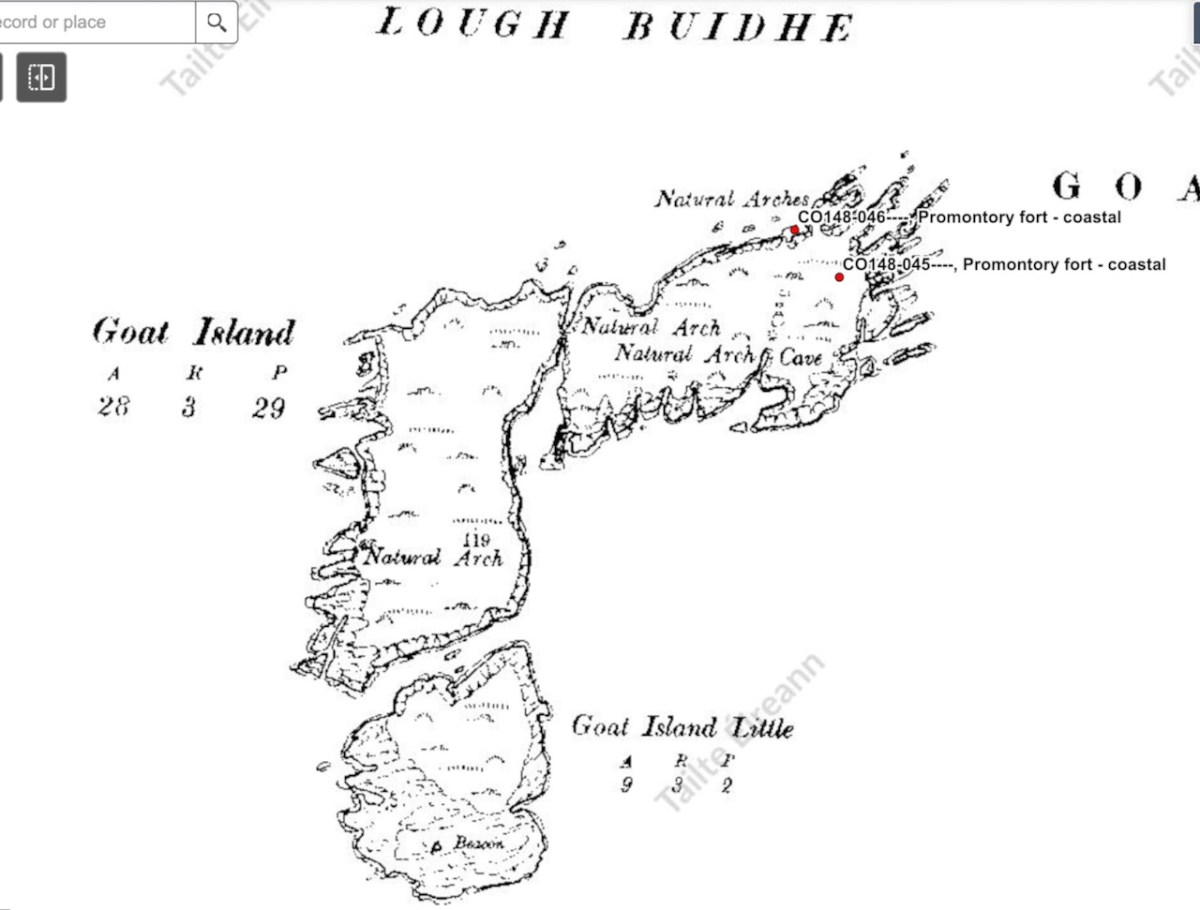

That islet is called Illaunricmonia, which translates, improbably, as Island of the King’s Copse, although it is called Turf Island on the Admiralty Chart. The sea between Goat Island and the mainland is labelled, on one of the early OS maps, Lough Buidhe, meaning Yellow Sea. All in all, a curious and seemingly inapt set of names that hint at more history that appears at first glance.

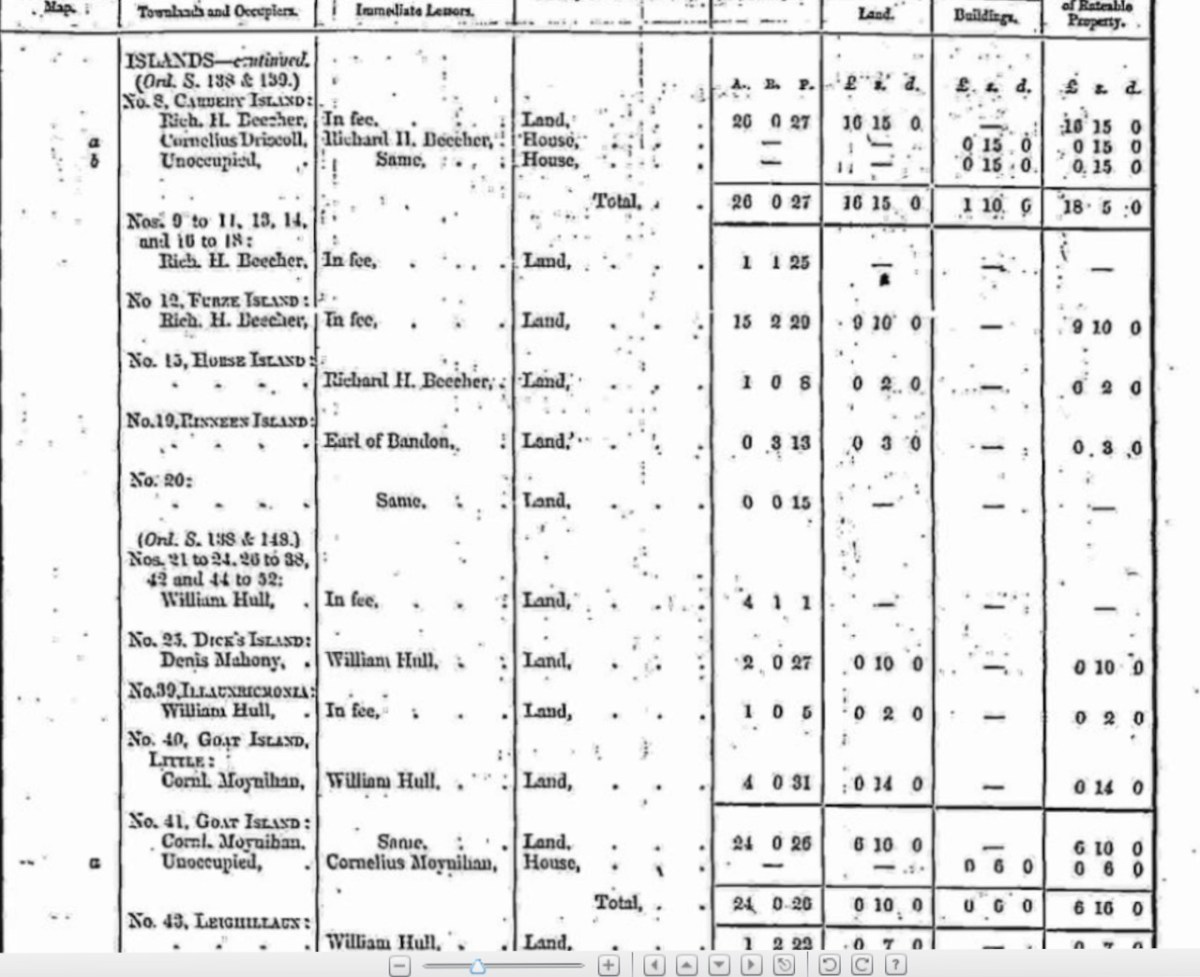

Griffith’s Valuation tells us both islands were owned by William Hull and Leased to Cornelius Moynihan. In the mid-nineteenth century, Goat Island Little was worth 14s and Goat Island 6£ 10s, while Moynihan’s hut was worth 6s. There are traces of lazy beds, visible even on the aerial photos – it’s hard to imagine how difficult it must have been to live here. Neither island has an obvious landing place but I understand it is possible to land on Goat Island if you know what you’re doing.

Not much history – but lots of geography! This was once one island, and probably joined to Long Island, which itself is one of a string of continuous islands off the coast. The cleft which divides it into two Islands probably started off as an indentation – and there are more indentations and developing clefts and fissures. Some of these now form sea-arches and at least one will eventually collapse, creating two island out of Goat Island.

We could see right through the crack at the join point.

The only structure on Little is a masonry beacon. Dan McCarthy in an entertaining piece for the Examiner, give the following account of the beacon.

Goat Island Little . . . was deemed suitable in the 1850s for the construction of a beacon to aid navigation for boats entering Schull Harbour via Long Island bay. A second beacon was constructed at Copper Point at the west end of Long Island. How the workers and boatmen managed to land themselves, as well as the stone, cement, and other materials needed for construction can only be marvelled at. In the end, the structure reached almost 5m in height and weighed 250 tonnes when it was completed in 1864. It was repaired in 1961 when 40 tons of gravel were brought from Schull to reinforce the foundations. However, The Skibbereen Eagle newspaper . . . recorded its distaste at the new construction. “These celebrated structures, finished at last… but to what order or style of architecture they belong we have been unable to discover. We have however been informed that, like their neighbour at Crookhaven, they are neither useful nor ornamental, as in the day time they are not required, while at night they can not be seen.” The newspaper went on to recommend that, as in Normandy, the head of the gurnet fish, when properly dried, be filled with tow (wick) from which a brilliant light emanates when lit. Thus ‘an inexpensive and brilliant light would be produced, and the effect, no doubt, would be exceedingly useful and picturesque during the ensuing dark winter nights’.

While we don’t endorse the gurnet fish alternative, we do have to admit that this is not the prettiest beacon, being remarkably phallic is its appearance.

And what about the goats? Yes, they are there, on the larger island, with nothing to disturb them. The population, I imagine, is kept in check naturally by the availability of food.

While a managed herd can be used to keep down invasive species (as in the Burren), in general a herd like this will just eat everything in sight and so John Akeroyd and the team who wrote The Wild Plants of Sherkin, Cape Clear and Adjacent Islands of West Cork, say that there are few plants to record and that the islands are of more interest for their birds than their plants.

Nicky is familiar with these waters so I knew I was in good hands. We set out shortly after nine, leaving from Rossbrin Cove, looking resplendent in the morning sunshine.

We passed Castle Island, the entrance to Schull harbour, and then Long Island.

Our first glimpse of the islands was through the rocks at the end of Long Island.

As we approached, the cleft loomed ahead and soon we were in it!

I switched to my iPhone, which does a better job of videos like this than my camera, so come with us now as we venture through the gorge, trying to avoid the very jagged rock right in the middle of the passage. You can view in YouTube by clicking on Shorts at the bottom of the video.

I’ve done it – fulfilled the ambition of many years and gone thought the corridor to the magical realm! There’s more to the story – we didn’t just turn around and go home, but I will leave that to the next post.