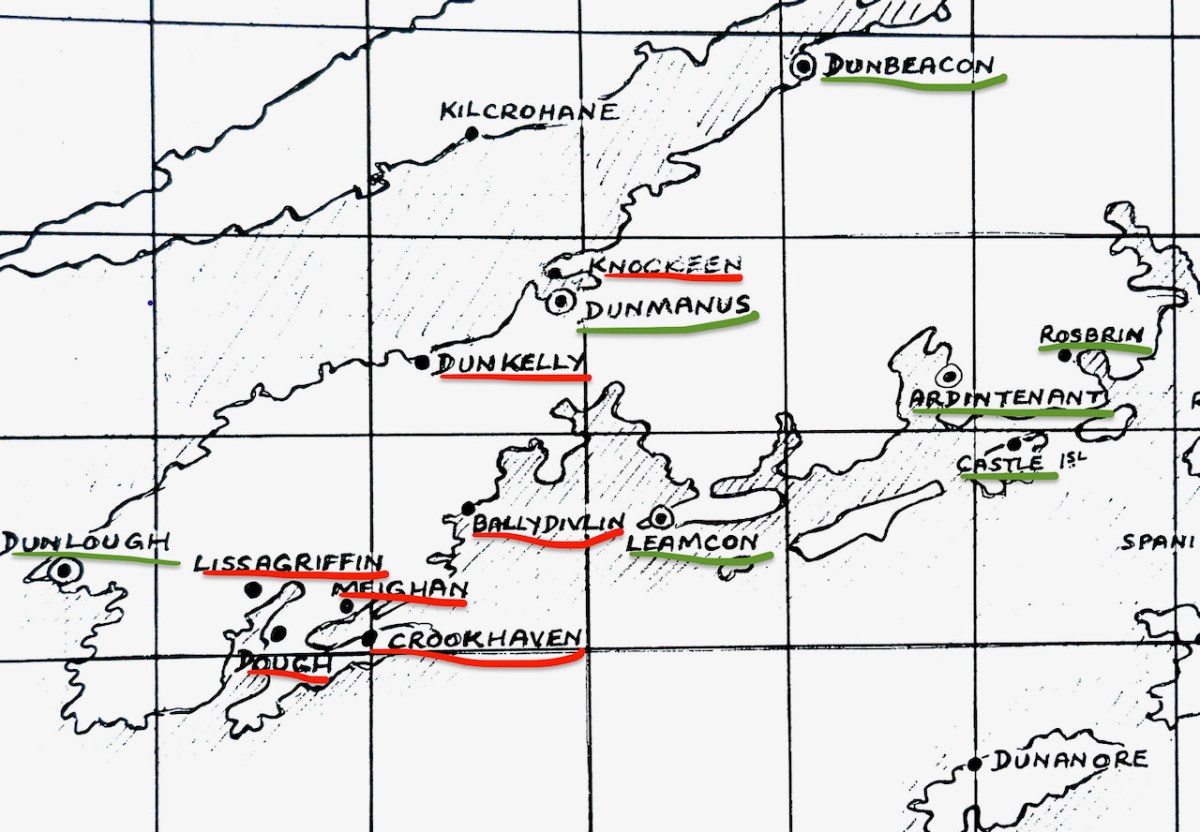

This is a bit of an epilogue to my Signal Success in Irish Engineering series (although that is not yet complete!). Here is the site of a Napoleonic-era Signal Tower in West Cork – but the tower itself has completely vanished! It’s no 28 on the map which accompanies Bill Clements’ book – Billy Pitt Had Them Built – Napoleonic Towers in Ireland (The Holliwell Press 2013) and it is given the name Glandore Head. We recently visited friends who have a house in the townland of Reenogrena, which is south-east of the village of Glandore and its extensive natural harbour. The topography of the area is soul-stirring – that’s probably an understatement: look at the view of the coastline there, above, and the distant views both west and east, below.

We were fortunate with the day we had. The benign weather gave us a possibly false sense of security as we explored a wild, riven coastline. We could well imagine how exposed we might feel there in one of West Cork’s severe storms: our climate-changing extremes are becoming ever more prevalent. But on this occasion we were confident enough to venture to the very edges of the land, always conscious that humans had settled in these remote places many generations before us.

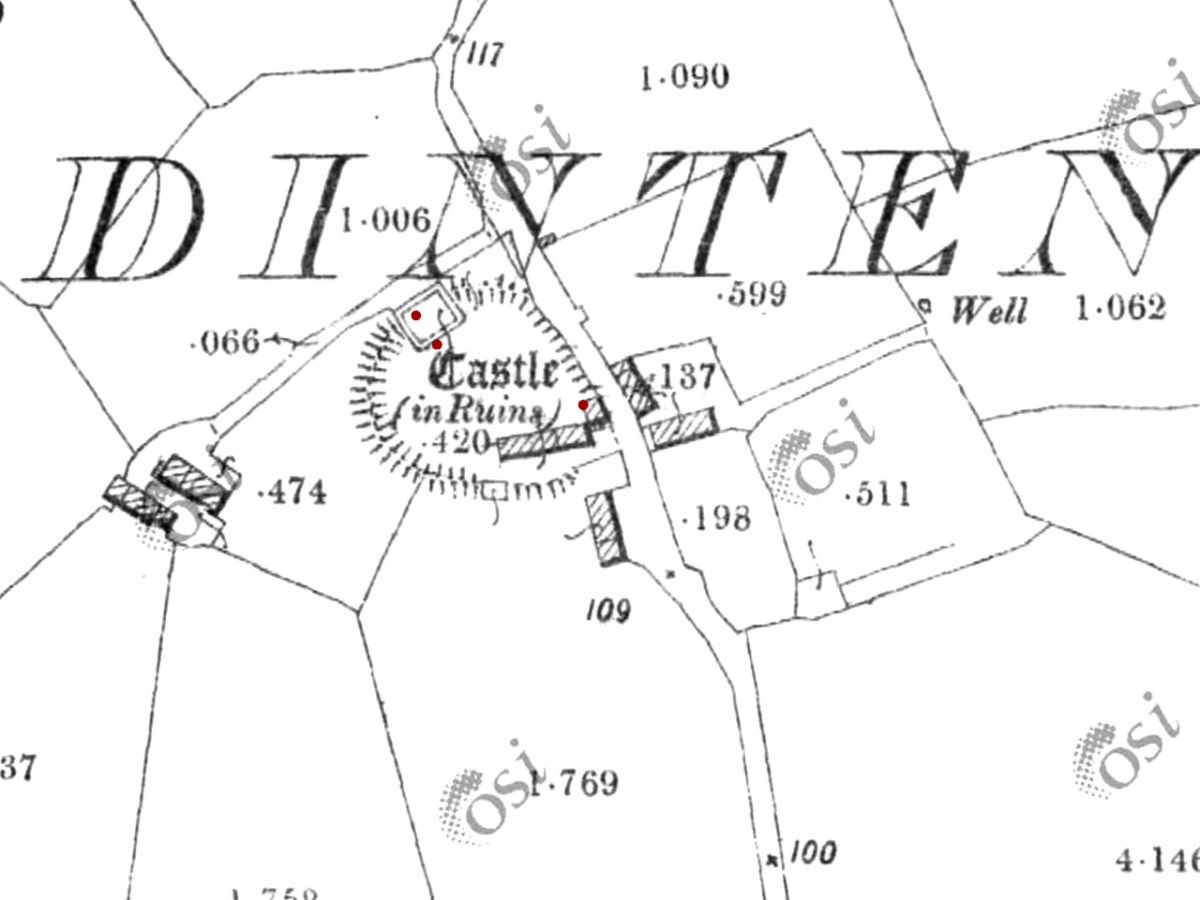

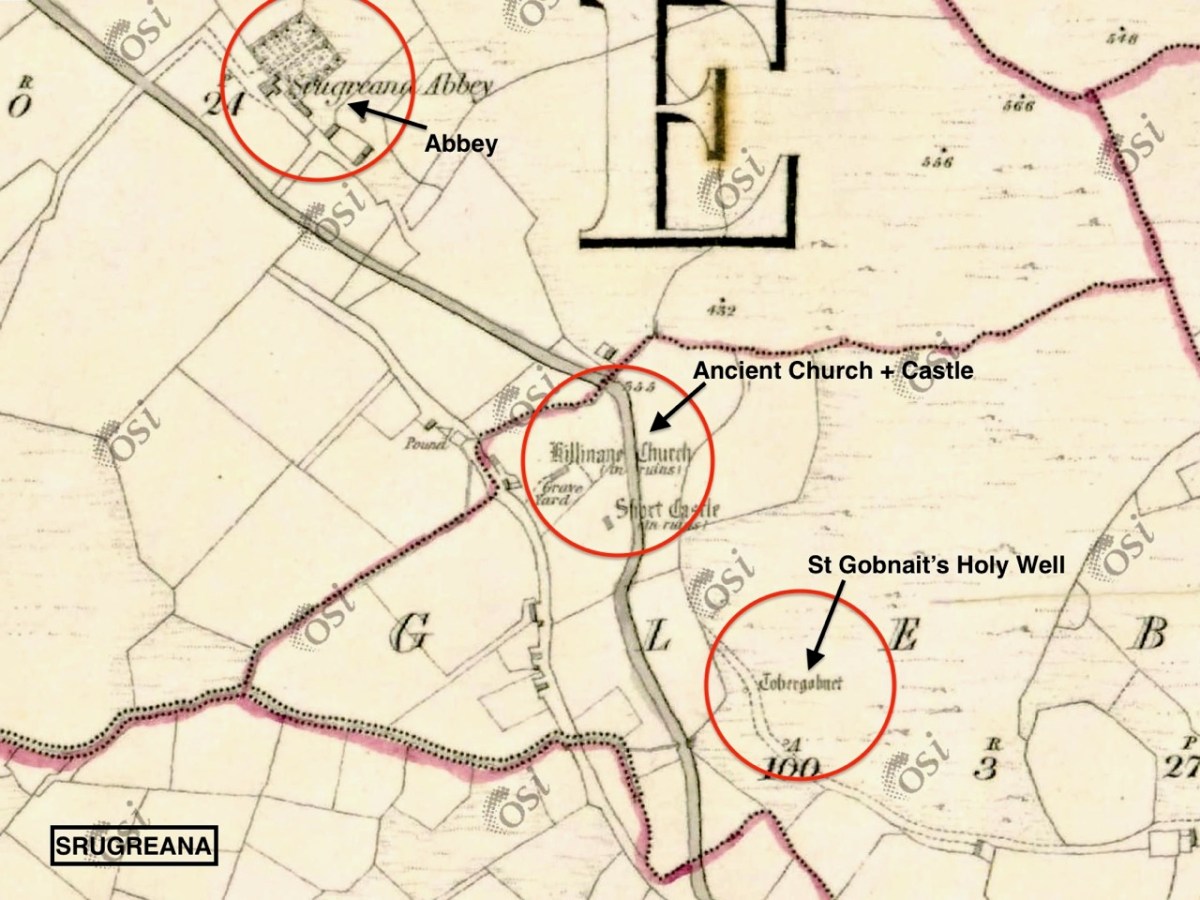

There is nothing left of the signal tower at Glandore Head, which would have been constructed between 1801 and 1804. The site has now been taken over by a recently built house which enjoys the excellent views in all directions. In the picture below it seems that the tower was located in the area of the earth-sheltered garage. We know more or less where it was because it appears on the earliest Ordnance Survey maps from around 1840. Even by then the structure itself had lost its original function, as the threat of Napoleonic invasion had passed, but it is labelled as a ‘Telegraph’. On the later 25″ map – dating from the late 1800s – the site is marked as ‘Tower in ruins’.

Centre – the earliest 6″ OS map; lower – the later – and far more detailed – 25″ OS map. It’s interesting to compare the two versions. The accuracy of the later map in terms of topographical detail and humanly constructed features – buildings, trackways etc is very noticeable. Below is the contemporary aerial view. 50 years separate the two OS maps, while the satellite image is 100 years later again.

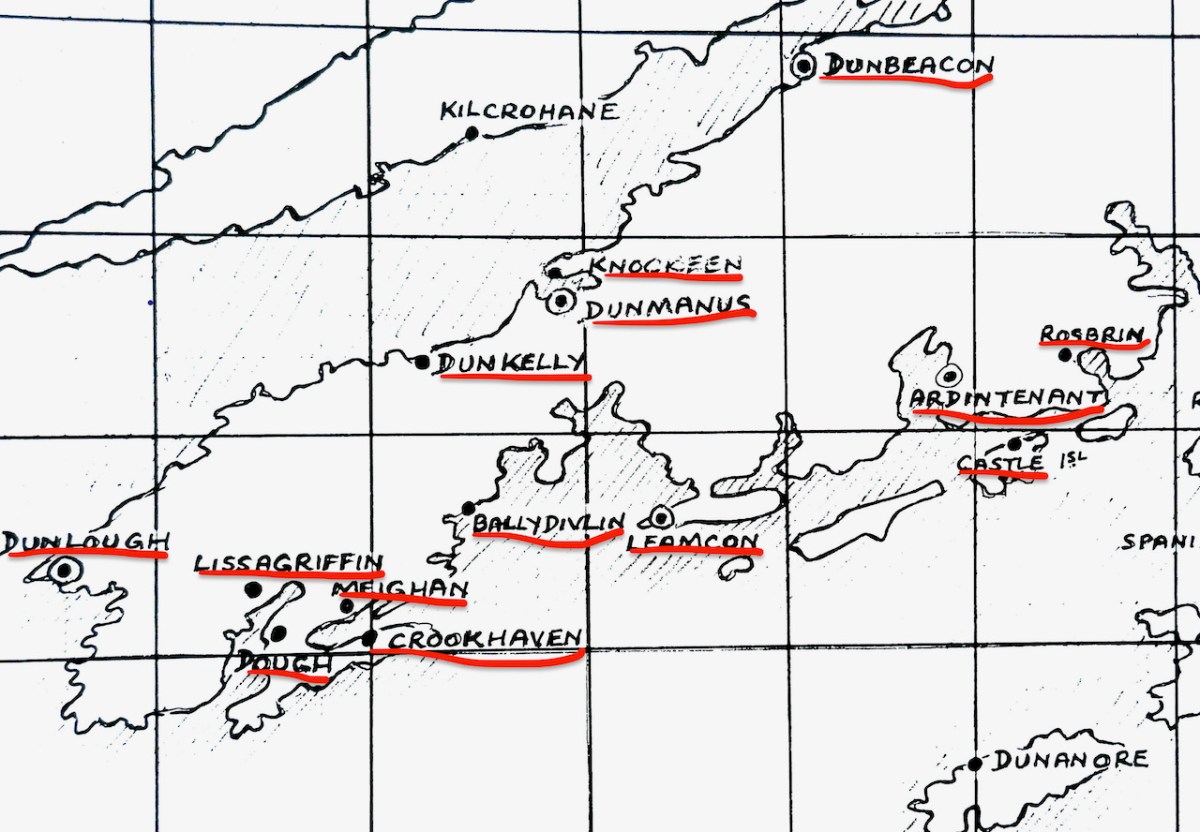

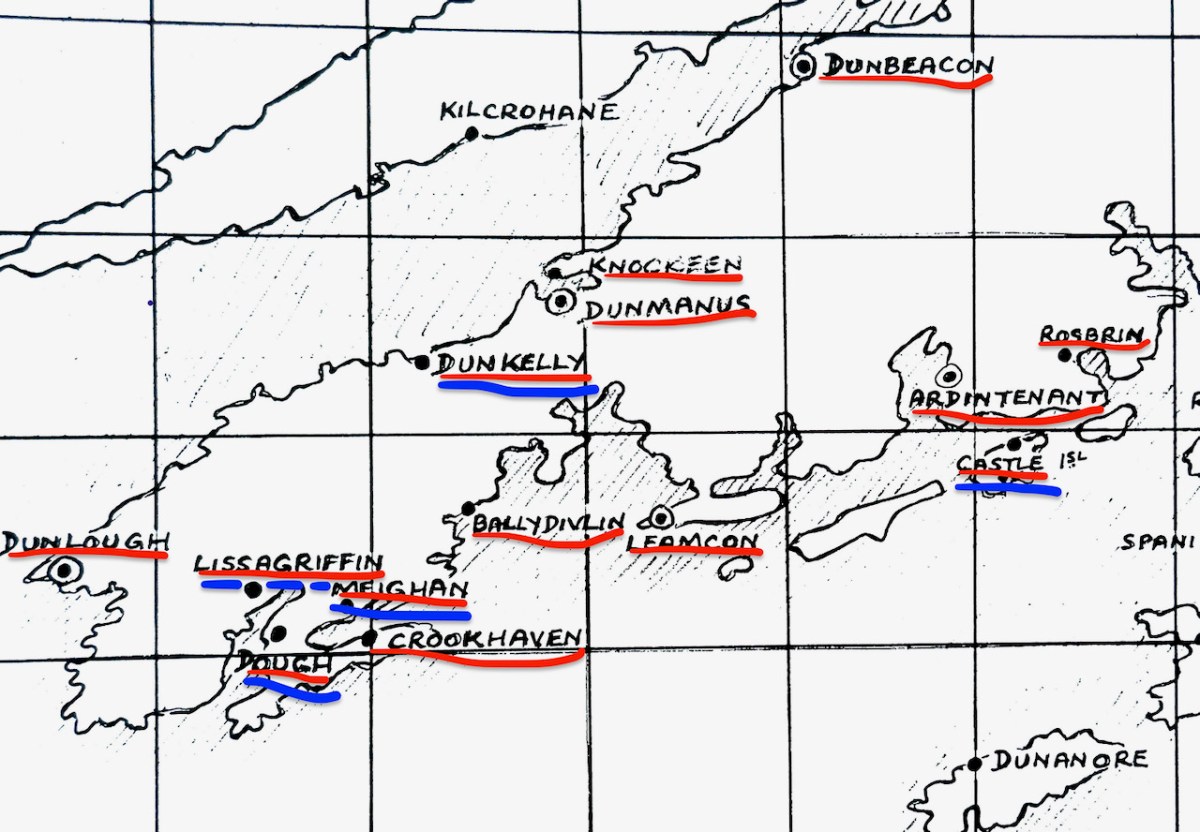

The reason why I like to examine and compare the mapped information is my interest in reading the history of a place through its landscape, and this particular vignette of West Cork is a prime example of the process. Firstly, the signal tower location was chosen because of visibility to other significant places on the coastline which are in view: the towers at Toe Head to the west and Galley Head (Dunnycove) to the east (below).

Next, look at the ‘Coastguard Station’ site. This is marked on the c1840 OS map, but not on the later 25″ map. But that later map does show a number of buildings on that site. As you can see from the aerial view, there are only the remnants of buildings now. Also the older map shows no roadway or track accessing the ‘Coastguard Station’ – it could only be reached by crossing fields. Here’s a closer look at this group of ruined buildings today, followed by some of our photos.

While it is likely that there are old coastguard buildings amongst these ruins, it seemed to us equally possible that we were also looking at the earlier remains of a settlement – cottages and cabins. Records of the area are scant. There’s nothing we found – apart from the OS maps – to give any further light on what we were scrutinising. Surprisingly, very little information is available on the early years of the Irish Coast Guard service, other than its establishment as the Water Guard, or ‘Preventative Boat Service’ in 1809, initially under Navy control but from 1822 part of the Board of Customs. From this we might assume that its purpose was to intercept smuggling operations, rather than to give any assistance to seafarers. Incidentally, it is important to note that in Ireland the name has always been two words: Coast Guard.

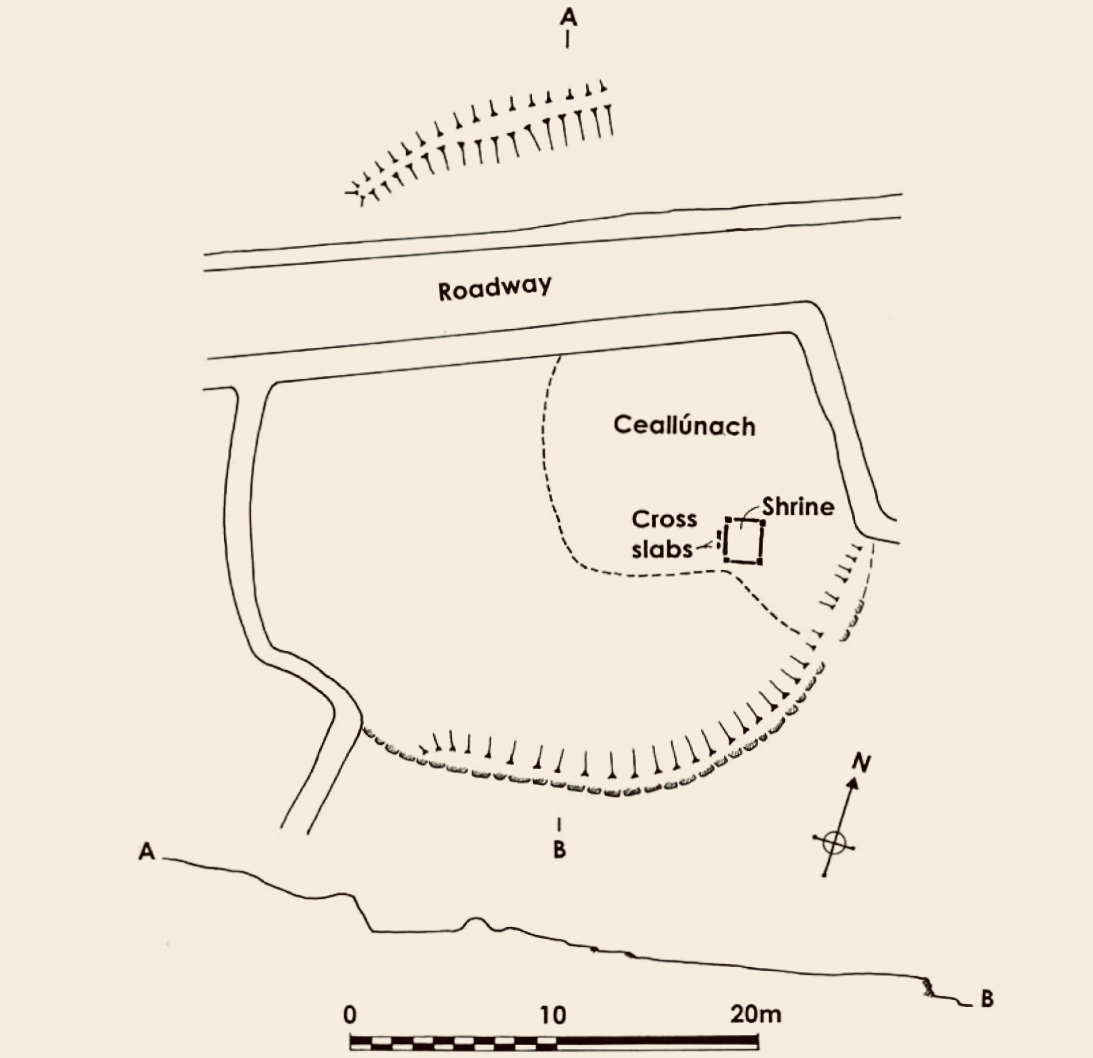

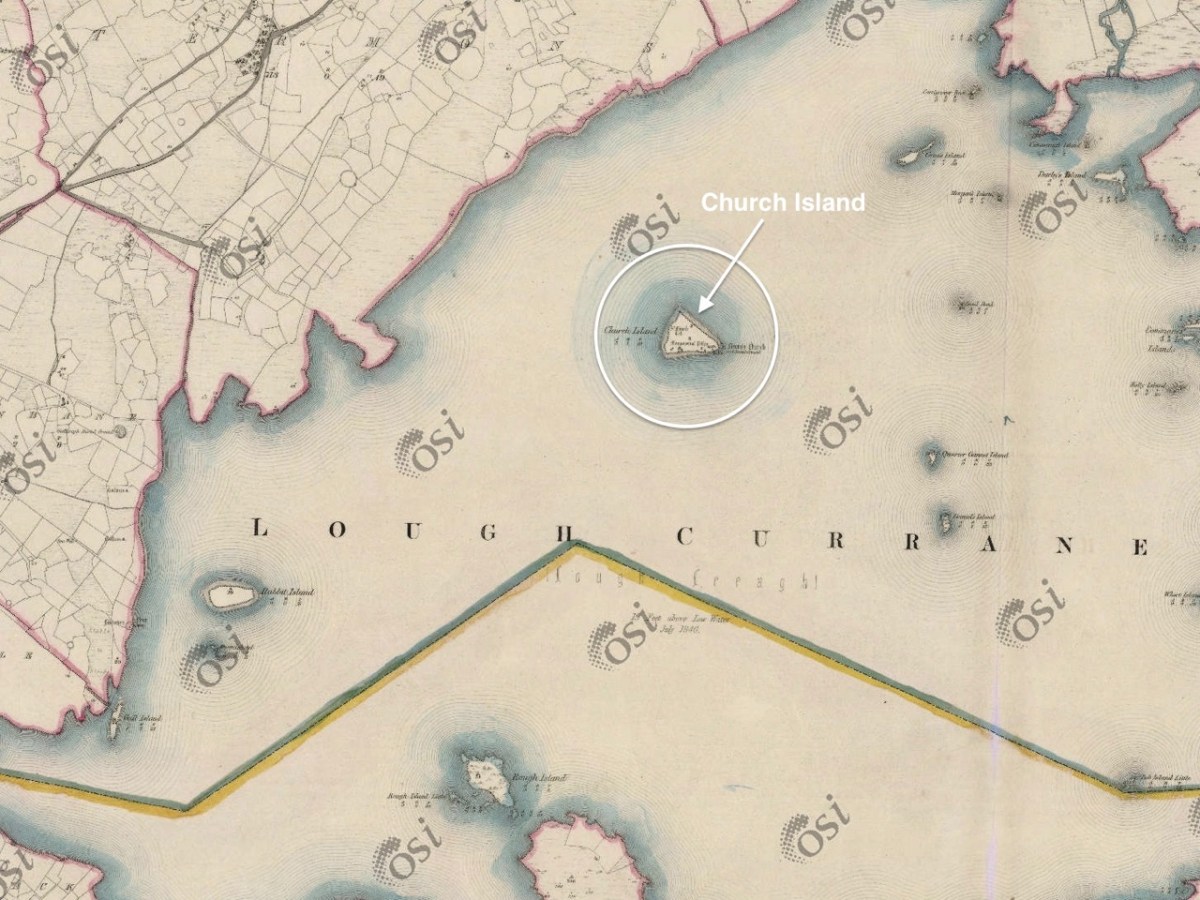

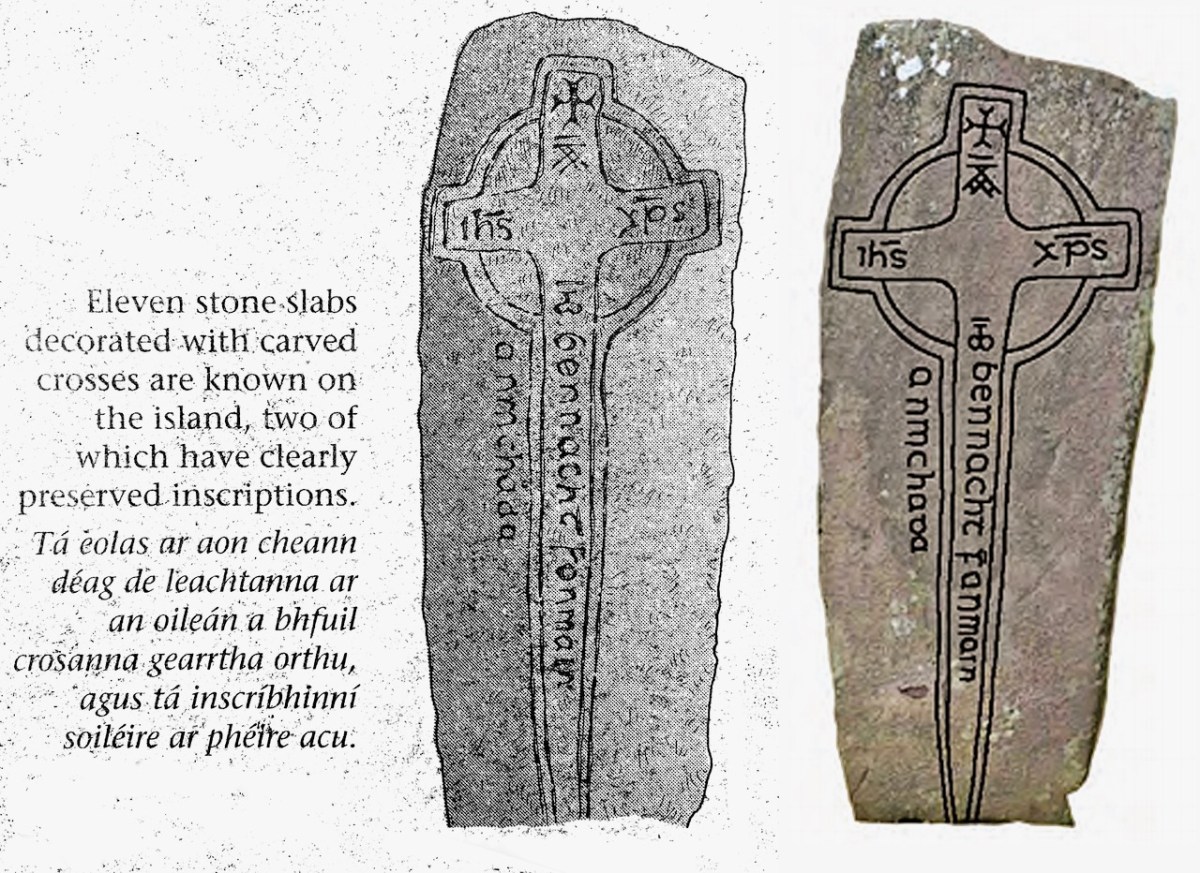

It’s easy to see that this hostile coastline – which would not be benign to small fishing boats – would nevertheless attract subversive landings. The only nearby access to the water is Siege Cove, to the east of the Coast Guard site. The upper photo depicts the curiously named Cooscookery inlet – not a good landing point, while the lower is Siege Cove – itself a difficult climb to the fields from sea level. The names of the topographical features would be a good study in themselves – and might reveal some hidden history: Coosnacragaty, Black Hole, Rabbit Cove, and Niladdar. The small burial ground is known as Kilcarrignagat (it means the ‘church at the rock of the cat’). That’s the overgrown trackway leading to it, below. It is of particular interest – partly because you wonder what communities it served, but also because it seems to have been established in a previously existing ring-fort or cashel.

Further yet to the east, and directly above Siege Cove, are the distinct remains of a defensive structure, partly taking in natural outcrops but also built up with stone. This is likely to be indications of the first habitation in this area – perhaps a thousand years ago. There seems to be at least one promontory fort here, and Finola will take up that subject in this locality in future posts (she has already tackled examples elsewhere). It seems to me that this whole coastal region would be worthy of a detailed archaeological study – UCC take note! Meanwhile, we can only express our gratitude to friends Michael and Jane for introducing us to the many wonders of their own territory.

Addendum: After I had published this post I discovered an excellent photograph of Siege Cove and the coastline in this area taken from the sea. I cannot find a contact for the photographer. I do know his name is Tim, and that he publishes an occasional diary of his journeys in a boat (an Ilur based, I believe, In Glandore). I hope he won’t mind me publishing this and including a link to his website.