There’s this brilliant young man, JG O’Donoghue, who combines the best qualities of researcher and sketch artist to produce outstanding illustrations, especially of heritage subjects. I’ve been a fan of his on Facebook for a while, but recently I saw the full extent of his talent.

Kilcrea Castle, Co Cork

You see, he’s done this job on tower houses. I’ve been studying tower houses for a while, especially the tower houses of West Cork (see my posts here and here and here) and recently I gave a talk about them in Ballydehob. So I recognise accuracy when I see it, as well as a meticulous attempt to be true to both published accounts and his own close observations. He has generously allowed me to use his drawings in this blog post, as well as his own words, slightly edited to fit the length of a blog post. So this is not my post, really – it’s his, as you’ll see if you head on over to his own blog, or follow him on Facebook. Since much (but not all) of what follows is based on Kilcrea Castle, Near Ovens in County Cork, I have included some of my own photographs of that site, to give you a sense of what it looks like on the ground.

JG Writes:

The Tower House

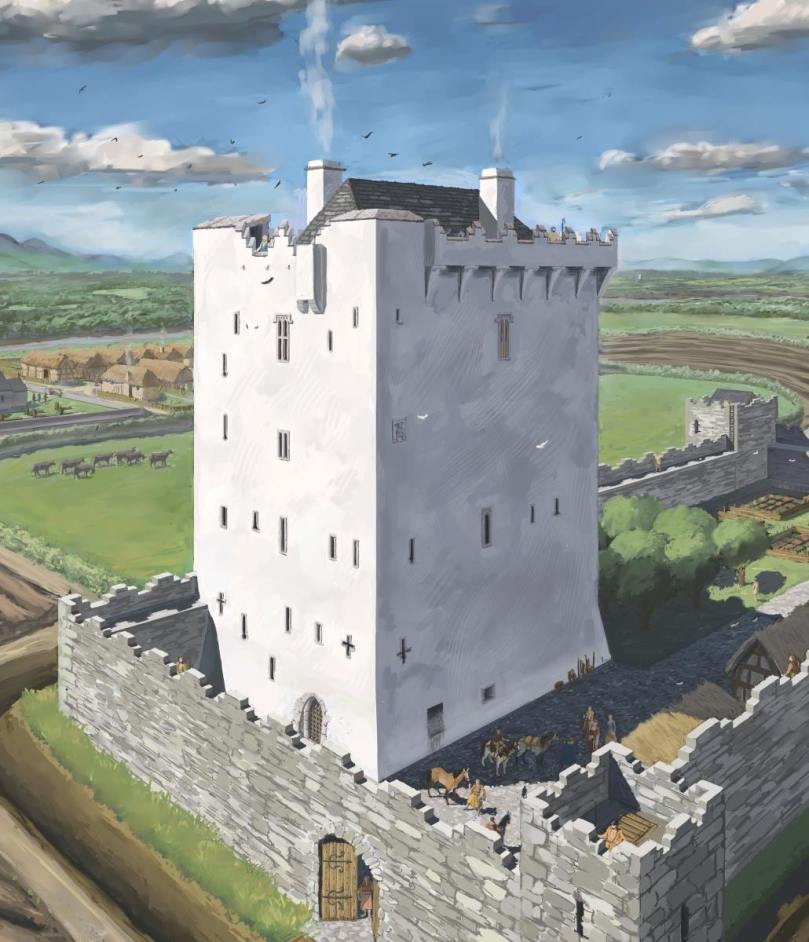

Tower houses are a type of late medieval Irish castle, believed to have originated around 1300, or sometime within the 14th century, but most are probably from the 15th to the 17th centuries. By the 17th century, this would have made Ireland the most heavily castellated part of the British Isles. The tower house signifies changes in Ireland: on one hand it shows a resurgence in Gaelic power in the west after years of decline following the coming of the Normans in the 12th century. On the flip side it is a sign of the collapse of centralised power in the form of the English monarchy and a rise in decentralisation.

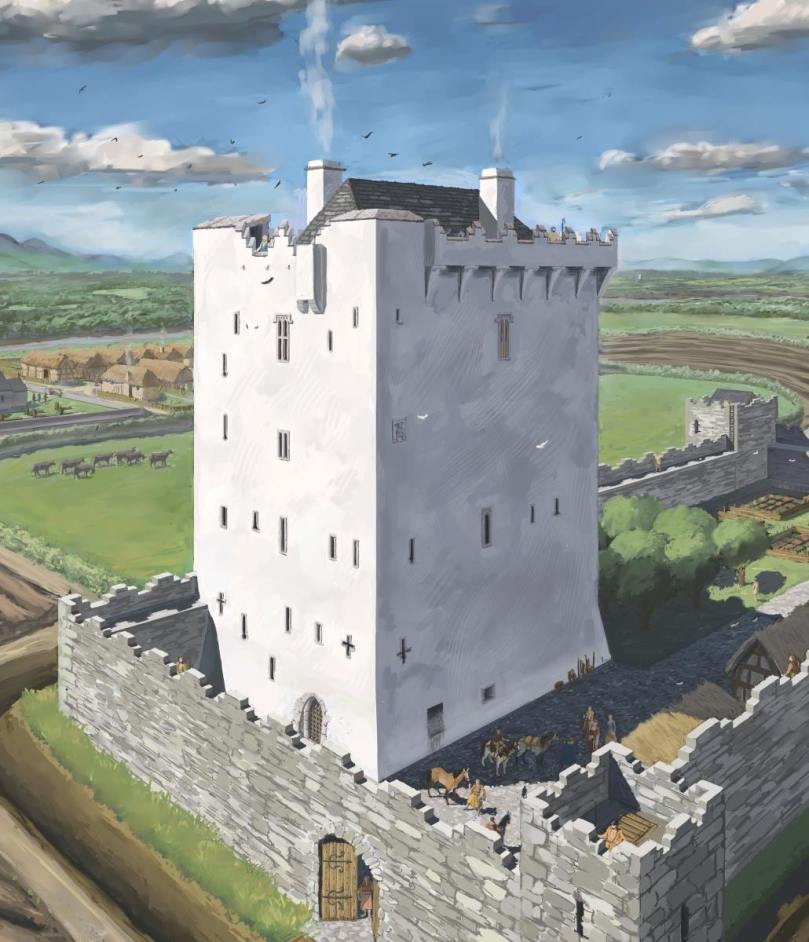

One tower house in five has a bawn wall in Ireland. The bawn is the external wall you see attached to the castle shown here. The actual design of the tower house itself though is nearly entirely based on Kilcrea tower house, in Cork, my favourite tower house and one which I have visited a few times and read extensively on. The only changes to the overall design of Kilcrea was the inclusion of a second chimney for the kitchen room inside, and the machicolation. I added these elements so the castle would be more representative of tower houses as a whole. Also the crenellation (the regular gaps in the walls at the roof & bawn, which provided cover for archers) in the castle are a style specific to late medieval Ireland. The bawn crenellations are based off Blarney Castle.

The bawn walls and corner tower

Notice as well how white the tower house is? This is probably how most tower houses would have looked, as they were coated with a substance called harling, a mixture of limewash and crushed pebbles. Because of this, commentators at the time often mention the white gleaming castles of the Irish, as you can imagine these would have been visible for miles around and been quite a symbol of power and prestige. You may also see the little figure on the dark side wall of the tower house: this is a sheela-na-gig, a type of sculpture common in Ireland at the time, this one is based off the one in Ballynacarriga Castle.

This is the sheela-na-gig from Ballynacarriga

Tower houses are believed to have been surrounded by mixed farming, some cereal with animal husbandry too as shown in the illustration. Often they are found associated with churches and friaries, some were even built attached to churches, and some probably weren’t too far from some sort of clustered settlement. Note as well the dry moat. Not all tower houses had moats, but some did, like Kilcrea, so I included it here.

Notice also the slight batter (where the wall comes outwards at the bottom to defend against a battering ram), also in the bawn towers, which is based on Kilcrea & Barryscourt. As you can see though, the real bling in the tower house is the top of it, this is where most showing off happened with turrets, crenellations, chimneys, gabled/pitched roofs and machicolations, as shown here. Another place they showed off was the ashlar (fine finished masonry) windows. The top floor in Kilcrea was believed to be the hall, with the floor directly below the lord’s chambers. Hence they have the nicest windows, especially the hall floor, which had 4 large windows as shown.

One of the windows on the top floor

Also notice the variety of windows: some were narrow slits just for archers to fire from inside, others have the addition of a cross slit, which could be used by crossbows too and then there were others with either triangular or circular holes, these were for later fire arms. Some windows even had all three as shown here in the 1st floor window in the dark side of the tower house, the one closest to the light. All these windows, except for the decorative ones on the top floors, would have been splayed inwards allowing maximum cover for archers.

Inside the Tower House

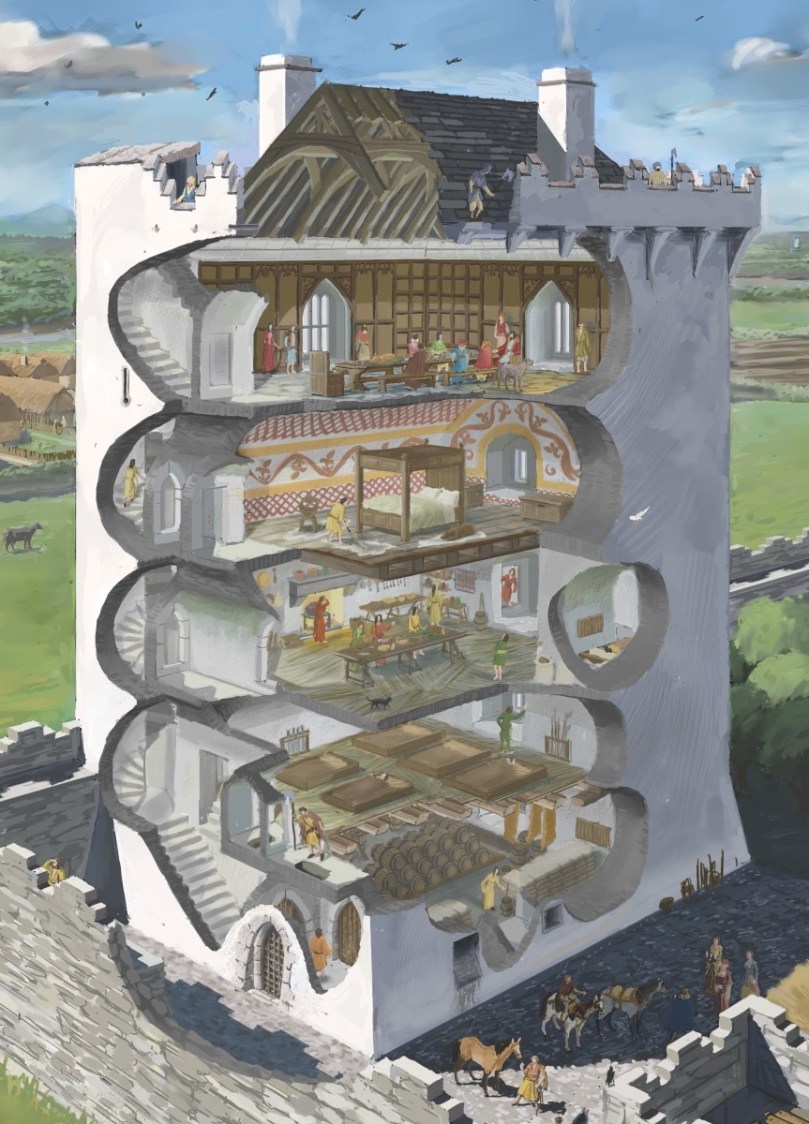

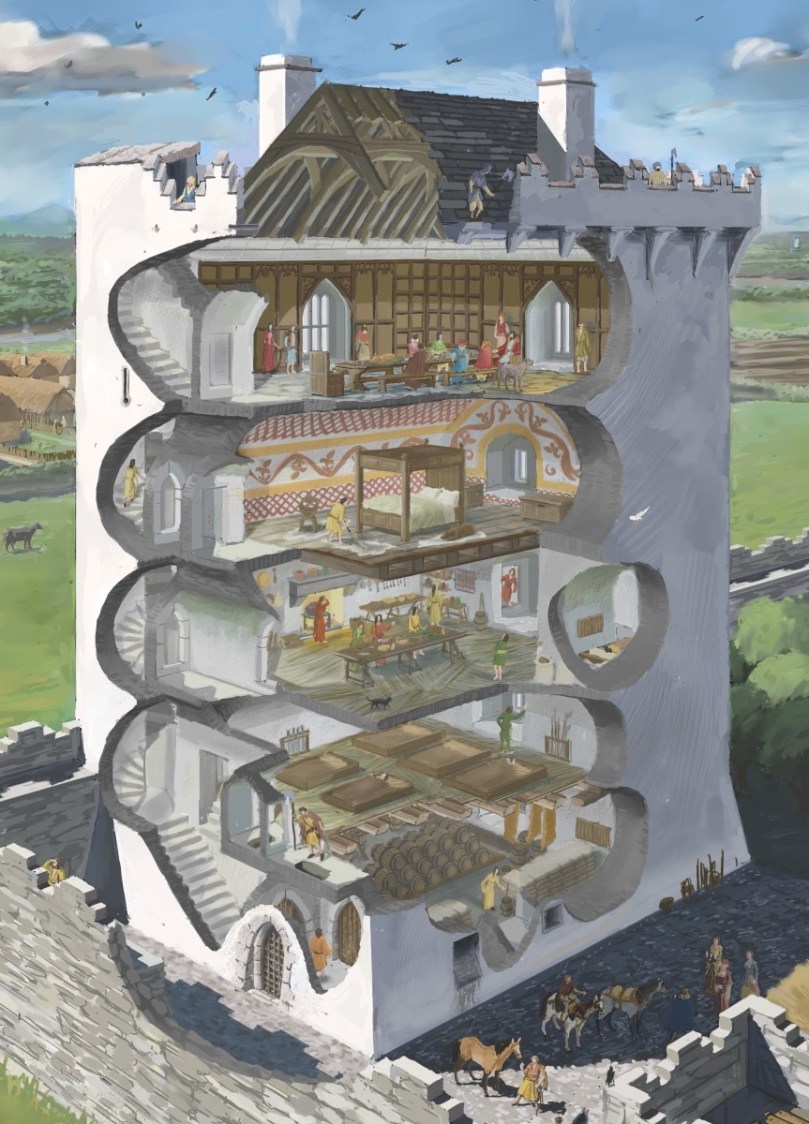

Ground Floor – here is a cellar, as in Stanihurst’s “house and castle” account of Mallow castle, 1584, “lower rooms whereof ar sellors vaulted over”. Here various food and drink would have been kept, perhaps not just for the castle itself but for the wider community, acting as a safe house for everyone’s goods in case of raids. The floor surface here is very basic and is just beaten earth.

1st Floor – I have made into a sleeping quarters. There is mention in the historical recorded accounts of tower houses that they were used for sleeping and that there were beds without curtains, and you could sometimes fit three people into them. So here I have shown some rudimentary beds, not just for guests, but also for the guards and servants. The 2nd & 1st floors are also covered with reeds, this would have often been what medieval floors were covered with according to medieval accounts, which then on occasion would have been swept out and replaced. This room also doubles up as a guardsroom, as this floor was probably the last line of defence before the attackers get into the rest of the castle, so I’d imagine weapons would have been kept here for ease of access.

Entrance lobby with murder hole above it

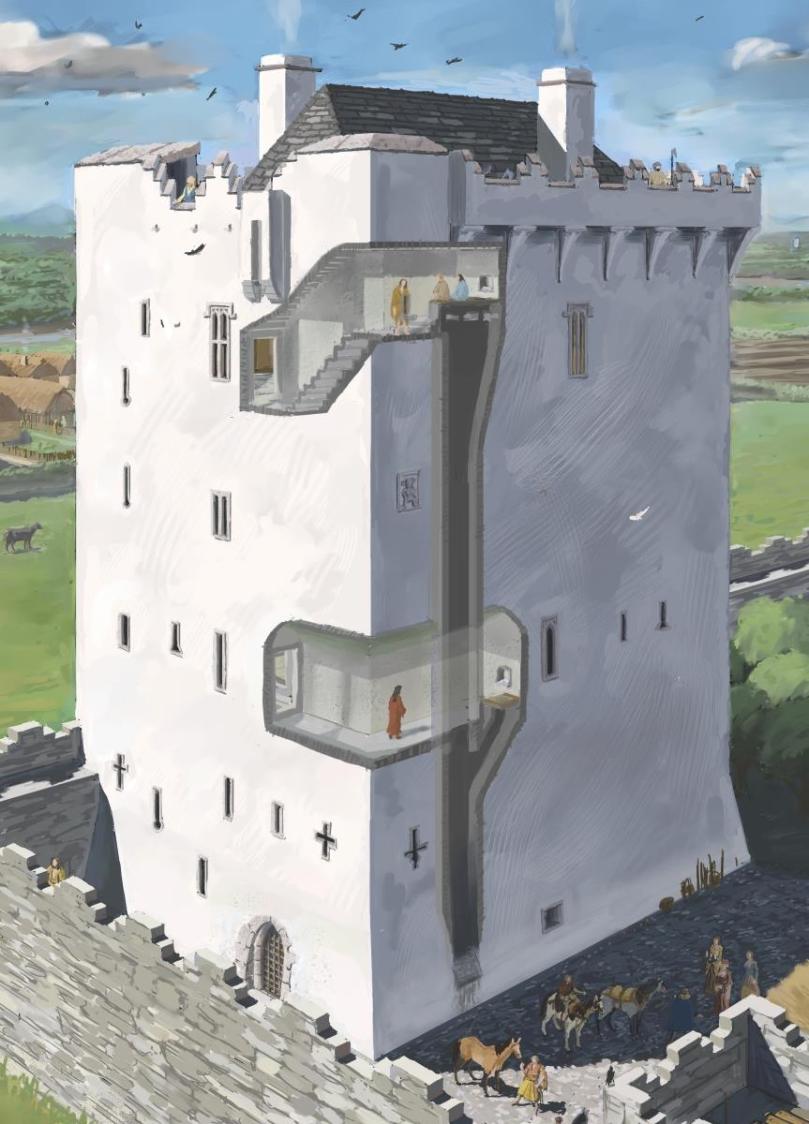

Murder Hole Room & Lobby – you will notice small rooms off both ground and 1st floors. In the ground floor this was the lobby, where for defence purposes, once you were past the main front door, you were greeted by two other strong doors, one to the rest of the tower house, another to the ground floor. Above this was the murder hole room, essentially a room with a hole in it, the reason for the dramatic name is that while you were trapped in the lobby between the two strong doors, you would be fired upon from above by muskets (apparently unlike what movies would have us believe, hot oil was rarely used). But in the day to day, these were probably used as a kind of door eye hole.

The mural stairs leading up from the main entrance. The bar across is said to be there to prevent a re-occurence of the time a cow wandered up to the second floor

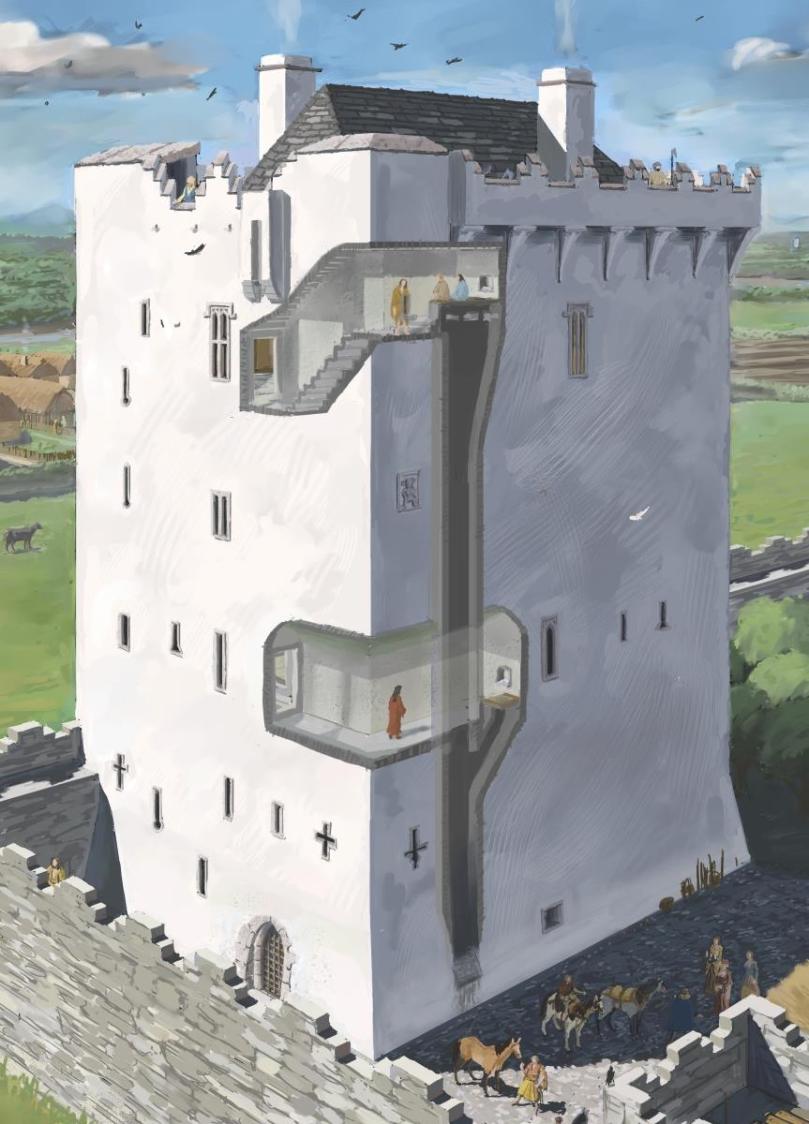

Stairs – in a tower house usually started as a mural stairs to the left of the lobby entrance, these were then carried on by spiral staircases from the first floor up to the 4th floor, which then had another set of straight stairs leading to a small spiral stairs to the wall walk area. This was probably defensive in nature, so it was harder for the attackers to take the spiral stairs and wall walk. This last set of stairs was usually hidden within one of the window embrasures at the top floor, this was a common feature in southern Ireland.

The ground floor with window embrasure to the left. Above it you can see the corbels which would have supported the first floor

2nd Floor – shows a kitchen with some sleeping quarters off in the mural chambers around the main room, these were L shaped rooms and could be accessed via the window embrasures of the main room. You can see one person leaning out of one such a door, having a word, while another person is sleeping inside another L shaped room.

Entrance to one of the mural chambers

Kilcrea’s main room was probably more sleeping quarters, but in some other tower houses which had fireplaces at this level there is speculation that these were the kitchens. Most kitchens would probably have been external though.

3rd Floor – Here I created the lord’s room: situated between two floors with fireplaces, this would have been quite a warm room. It shows a typical late medieval bed, chests used for storage and a Savonarola chair, or X chair, in front of the bed, these were quite common throughout Europe at the time, made in Italy. The third floor has its floor boards shown rather than covered, with the occasional fur. Also note the paintings on the wall. There is mention in some written sources that the Irish decorated their walls with branches: I found a piece of metalwork from late medieval Ireland with this very design, the Clogán Óir Bronze Bell shrine of St. Senan, which was early medieval with later alterations in the late middle ages. One side had a pair of dragons with floriated tails and above, branch and leaf ornament along the top, so I used that here, while the knot-work is based off other metalwork at the time.

4th Floor – This was the dining room. In the earlier periods there was always a large external hall to the tower house, made of non stone material, but as time moved on more and more of the the hall activities were taking place within the tower house. This dining room floor in Kilcrea had lovely large windows, not all of them surviving, some with double lights with ogee heads, as shown. I added a transomed triple ogee headed light as shown in the window on the left, which is typical of a late medieval tower house. These windows must have created quite a bright room. Rooms of this stature were probably decorated with ornate wood panelling as shown. No such panelling survives in Ireland, so these are inspired by ones in Britain. Generally tables at the time were long with benches and only really the lord would have had a separate chair. People ate with their hands, there were no forks yet in Europe and everyone had a personal knife with which to cut their food.

Roof – the 4th floor in Kilcrea had very thin walls, in comparison to the rest of the tower house, most likely to give it more space and air. The roof wasn’t gabled but hipped, resting on cornices as shown above the wood panelling. The roofs were often covered with tiles but many were probably thatched too. On the wall walk level, in the front, you can see there were holes at the bottom of the parapets. In Kilcrea some of the wall walk flagstones had chutes carved into them to drain away the rain. The other side (the shadow side) shows wall walk machicolations, which were extended floors with holes in the ground: these are based on Blarney Castle with its pointed corbels. Chimneys were also on the wall walk level and were to become display features in their own right, rising to great heights to carry smoke away but also to show everyone around how well the castle was heated (in later periods castellated houses had lots of chimneys as an extra form of bling).

The Wall Walk, with flagstone chutes designed to carry off the rain

Garderobes

Usually tower houses had 2 garderobes, as did Kilcrea, one for public and another for private use. In the case of Kilcrea both were probably public, but the upper one accessed from the dining hall had 3 holes in it, so probably had wooden seats with three holes for 3 people to use at the same time.

This upper garderobe chamber also had a window with a slop stone, which were small drainage basins underneath windows, which were essentially urinals (often found on stairs). The garderobe on the 2nd floor, is one of the 3 L shaped chambers off the main room. Garderobes were normally at the ends of passages in both Anglo-Norman castles and tower houses, to give more distance between the rest of the house and the toilets.

Inspector of Drains

Thank you, JG – for your talent in representing medieval life and for your generosity in allowing me to feature your incredible drawings! Go raibh míle maith agat!

Email link is under 'more' button.