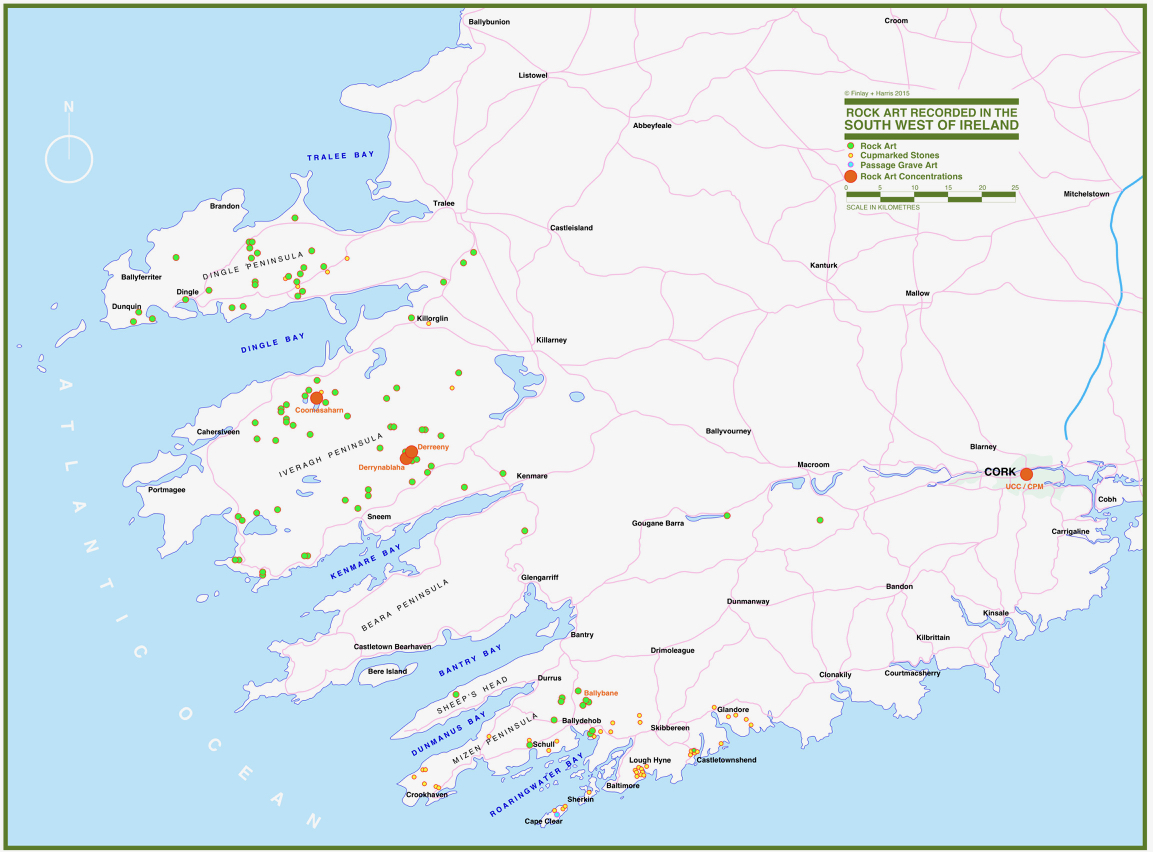

Gorteanish Stone Circle, near Ahakista on the Sheep’s Head Peninsula, is singular because it lacks ancient history. It doesn’t appear on the early Ordnance Survey maps and – to the best of my knowledge – no local stories or folklore have been recorded about it. It is a Bronze Age archaeological site, but it has apparently been overlooked until comparatively recent times.

It’s a short walk to the west out of Ahakista to the site of the stone circle. The way is marked by the stone above. Atha Tomais means ‘Tomais’s Place, and refers to Tom Whitty from Philadelphia, who settled on the Sheep’s Head in the 1980’s with his wife Suzanne and family. He is credited with having come up with the idea of establishing The Sheep’s Head Way – a series of footpaths covering the peninsula, and the project was put in hand by Tom and a local farmer, James O’Mahony, completed in (remarkably) just 18 months and formally opened by President of Ireland Mary Robinson in July 1996. During clearance work for the Ahakista footpath the remains of the stone circle at Gorteanish were discovered. It has since been suggested that there were stories of ‘old stones’ being hidden in the undergrowth. A footpath giving access to the stones from the nearby lane was duly completed and opened, and the inscribed stone marks this occasion.

This photograph shows the circle more or less as it was found in the 1990s. Four stones are standing, and others are lying prostrate.

Earlier this year, the decision was taken by Professor of Archaeology at University College Cork, William O’Brien, together with a group of students, to extensively study the site at Gorteanish. Their mission was to excavate the site where necessary to establish which of the stones had been standing and to see how feasible it might be to restore these standing stones in their original sockets, using only traditional methodology. A significant area around the whole site would also be examined to search out any evidence of human occupation and activity – and hopefully to provide a reasonably accurate dating for the circle.

Finola and I visited the site while the archaeological works were progressing (above). Yesterday (5 August 2023) Billy O’Brien (below) was on hand to give a detailed talk on the excavation and restoration work, and we could see, for the first time in many generations, the circle restored to its complete state: it now has all eleven stones standing.

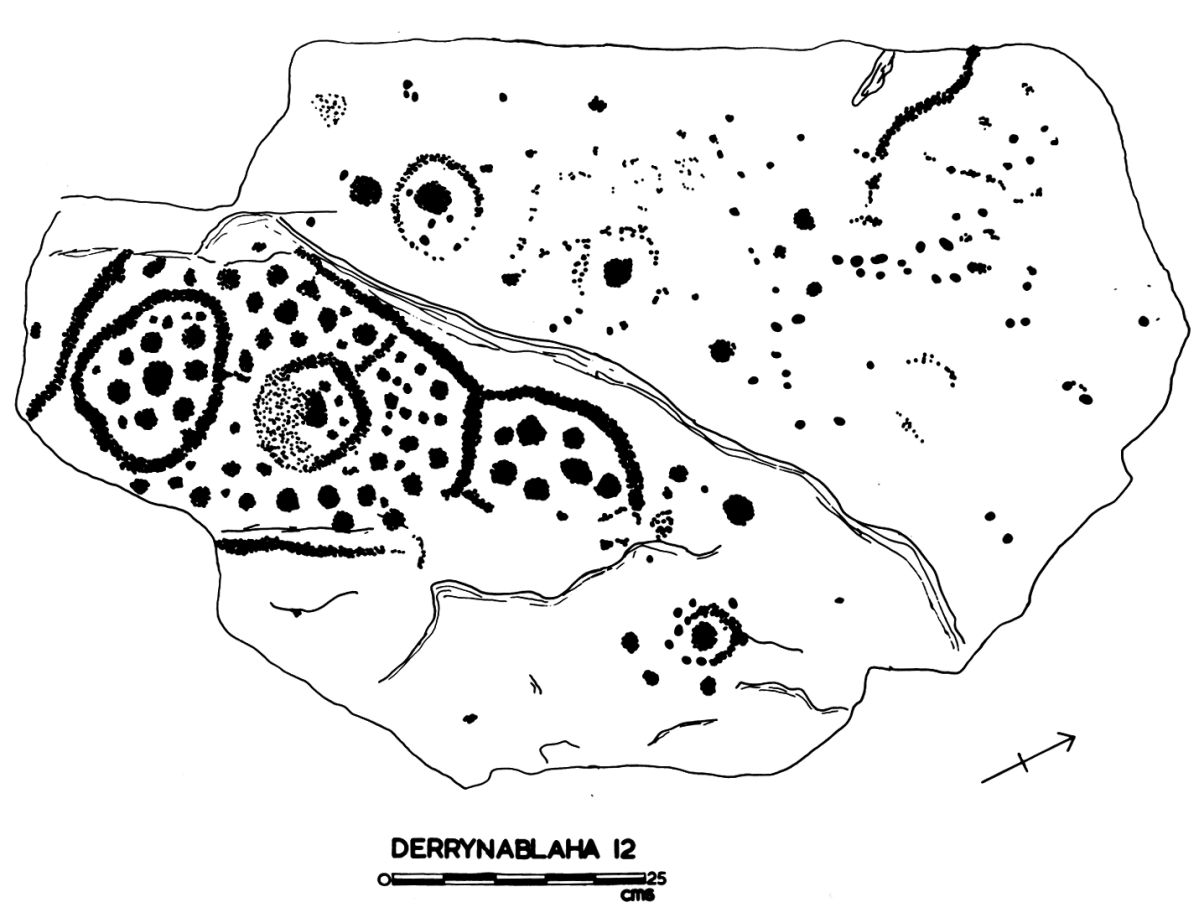

The view above shows a boulder burial monument situated to the south-west of the main circle. This has always been a visible feature of the site. A boulder burial (once called a boulder dolmen) is peculiar to Ireland. In fact it is found only in Counties Cork and Kerry. Finola has written comprehensively on this subject, here. It is usually a substantial raised stone supported on a bed of smaller stones:

. . . Boulder-burials are a group of prehistoric stone monuments of megalithic proportions, whose distribution is largely confined to south-west Ireland. Some 84 examples have been identified, 72 of these in Co Cork and the remainder in Co Kerry, where they occur both singly or in small groups of between two and four. They consist of a large boulder erratic supported by an arrangement of smaller stones, with no covering cairn or tumulus. Several examples are known which are centrally placed within stone circles . . .

Boulder-burials: A Later Bronze Age Megalithic Tradition in South-West Ireland

William O’Brien Dept of Archaeology, UCG 1992

A closer view of the boulder-burial at Gorteanish: it can be seen that the main ‘boulder’ element has split in two through the ravages of time. In the main circle, all the standing stones have been restored to their original (relatively shallow) sockets, and fixed using rammed small stones, following the evidence gained during excavation.

Most stone circles have a specific orientation. This can be seen by the shaping of the stones around the circle. In this case there are two clear ‘portal stones’ on the east side, directly opposite an axial stone on the far side (above). More usually, the stone opposite the portals is flatter, when it is known as the ‘recumbent’. In this case it is a substantial stone with a shaped top (detail, below).Perhaps this points to a feature on the horizon? Our calculations show that the orientation of this circle is towards the winter solstice sunset – just as at Drombeg Circle, not too far from here.

Yesterday’s event attracted a substantial crowd, eager to hear Professor O’Brien talking about this project. Many were no doubt surprised to see the site returned so faithfully to its original state. But – with stones standing – it has now become an iconic piece of archaeology. We are delighted that it is on our doorstep. If you want to read a deeper discussion on stone circles and their historical contexts, look at Finola’s post here – one of many that include the subject.

Another thing that Billy pointed out was the significant ancient stone wall that runs across the site; you can see traces of this above. In this view you can also see an elongated large rock apparently lying on its side. Some local commentators have suggested that this was once a very tall standing stone. If so, at about nine metres, it would have been spectacular! But the excavation confirmed O’Brien’s view that it was never standing, and has always been part of the landscape in its current position.

Also, an area of flat ground to the east above the site was closely examined, in case it revealed traces of any human use, but none was found. In fact, there were no signs of any notable human activity. However, one point that I found particularly interesting was that, in the centre of the circle, is a pit containing quartz stones. Quartz, that glinting reflective material that faces the much older main chamber at Newgrange (you can see a pic of it in this post), certainly catches the attention; it’s fascinating that the Gorteanish people – whoever they were – gave it an aura of importance by burying it at the focal point of this circle. The quartz has been replaced in the pit, after the excavation. Its position is marked by the only ‘alien’ element that has been introduce here – a pale coloured flat stone:

The larger earth-fast stone beyond this new addition has always been there: the site might have been constructed around it. It’s always interesting to see how people are going to react to a circle like this – here is someone’s recent contribution, also giving importance to the ‘magical’ quartz:

All in all, our day was exciting. It’s pretty special to see something ancient faithfully restored – and open for all to access. The seven fallen stones probably collapsed because of cattle rubbing up against them over centuries. That has been prevented now. We hope you will all appreciate – and enjoy – this new West Cork experience.