“…The fish are knocking at our doors but we haven’t a bucket to take them from the water…” – This was Father Charles Davis, Parish Priest of Rath and The Islands, appealing to Queen Victoria shortly after his appointment to the area in the 1860s. He and three Cape Clear fishermen had been granted an audience to explain the near famine conditions that still prevailed in West Cork, and the priest’s proposal to build a fisheries school and establish a new fleet of boats in the town of Baltimore.

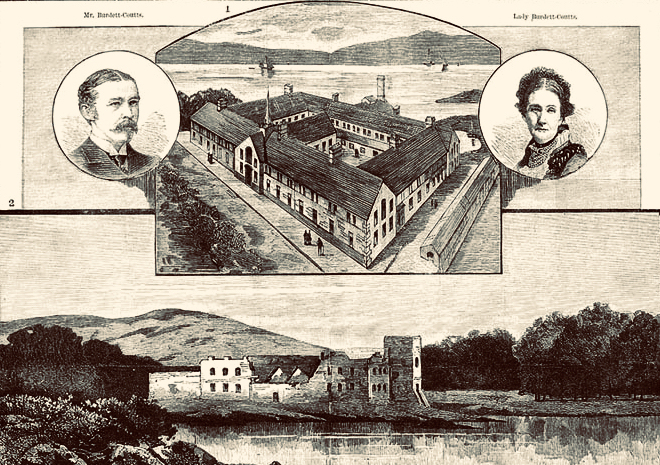

Header and above: the huge goods shed and boatbuilding slip that were established in Baltimore following Father Davis’s successful appeal to the Queen

Help came when the Queen directed the appellants to Baroness Burdett-Coutts – the richest woman in Britain: we met her in Flying Foam, my quest to find out as much as I could about the remains of an old fishing boat that lie submerged by the tide in Rossbrin Cove. That quest is ongoing – and has grown in complexity – but today’s little journey takes us to Baltimore, not too far from Rossbrin, especially as the foam flies. We have been to that lively little town many times (not least to enjoy the annual Fiddle Fair – this year’s is coming up at the weekend!), but never before have we taken a close look at the stories surrounding the fishing industry – and the extensive evidence of it which still exists.

I have always been fascinated by Industrial Archaeology, and I’ll search out any remnants of old workings, canals, railways and engineering structures that can be traced in the field, wherever I happen to wander. Baltimore offers a wealth of finds, and most of them can be traced back to Father Davis’s positive influence on the fortunes of the town in the late nineteenth century.

The big slip – where Baltimore’s own fishing fleet was launched and prospered, with the town’s working harbour in the distance: from there boats ply every day to Sherkin and Cape Clear

Prior to the work of Father Charles, Baltimore was a resting place and servicing centre for the large Manx fleet and boats from England and Scotland, all reaping the harvest of the sea on the fringes of the Atlantic. As the century progressed, the priest saw his vision realised: between 1880 and 1926 Baltimore was the largest fishing port in the country and 78 fishing vessels were registered locally. The local economy was also boosted by boatbuilding and net making, as well as providing a hub for the transporting of goods to and from all the inhabited islands of Roaringwater Bay.

Harsh, unpaid work – net making by the boys at the Baltimore Fishery School – later the National School

Father Davis pursued a previously conceived project of establishing a fishing school in Baltimore. A grant of £1,000 was made to this by the Grand Jury of County Cork, and the Treasury, at the instance of Arthur Balfour, Chief Secretary for Ireland (and later Prime Minister of Britain) granted £5,500 towards the completion and fitting-up of the school. In 1886 the Fishery School was formally opened by Baroness Burdett-Coutts.

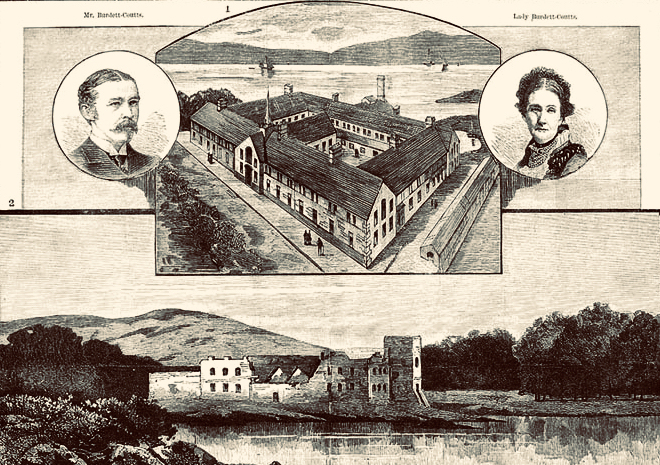

From an encyclopedia illustration: the Burdett-Coutts portrayed with the new Baltimore Fishery School in the 1880s. The picture below is of the medieval castle at Oldcourt, further up the Ilen River

Fr Davis was not yet at the end of his labours in connection with the fishing in Baltimore. He was aware that one of the great disadvantages under which the fishermen of the region laboured was the difficulty of transporting the fish to the English markets. This was ordinarily accomplished by steamers from Baltimore to Milford Haven, Wales. However, there were times when these steamers were not available, and it was necessary to send the fish via Dublin and Holyhead. In these cases the fish had to be carted from Baltimore to Skibbereen, with the result that the fish greatly deteriorated in transit. To remedy this problem, Fr Davis set about getting a railway link between Skibbereen and Baltimore. This project, when first started, seemed to have little promise of success, but Fr Davis was not discouraged. He enlisted on his side the sympathies of a great number of Nationalist members of Parliament and of many who were not of Nationalist politics. He also enlisted the powerful aid of Baroness Burdett-Coutts. In the end his efforts were crowned with success when a bill for the Baltimore railway was passed by Parliament. However, he never lived to see the railway line open on the 2nd May 1893.

(Notes from the Diocese of Cork and Ross)

Baltimore Station – the most southerly railway terminus in Ireland – is still intact today, although now deserted and derelict following a previous incarnation as a sailing school. Good Friday, March 31st, 1961, is a date which will be remembered by many in West Cork as the loss of a lifeline to the outside world. Despite ‘the greatest civil protest since the foundation of the State’, the West Cork railways closed down.

The three photographs above are borrowed from the blog Beneath the Summer Growth – an excellent site which has covered many aspects of Irish industrial archaeology. I could not find a direct acknowledgement for these pictures, which are the best I have found on the Baltimore line. Upper – the railway line at its furthest point, on Baltimore Pier (1961); centre – Baltimore Station when it was still working (1961) – on the left is the large goods shed; bottom – Baltimore Station in 1962, when the trackbed was being taken up

In spite of the loss of its railway, and the decimation of its fishing fleet, Baltimore thrives today as a working town – with its ferry terminals serving the Islands – and a popular West Cork tourist destination.

Baltimore Station and its accoutrements still very much in existence today, although now disused and with no plans for the future

At one stage there were seven trains every day out of Baltimore, all carrying fish for the American market. But the good times didn’t last and in the early 1950s the National School (formerly the Fishery School) closed. You may not want to know the full story of this institution: it has been told – starkly – by Alfred O’Mahony – who was a resident there between 1941 and 1947. The story entails abuses of many kinds: beatings, hunger, harsh conditions – the building was unheated and the boys had to endure the winter of 1947, the coldest on record in Ireland. I will quote a single example – the state of the sanitary facilities:

The outdoor lavatories were wedged between the play hall and the laundry. The ten cubicles there had splintered and rotted half-doors hanging from large rusted hinges. The large roundels in the cubicles had once supported the original giant chamber pots which, on becoming rusted and holed, were sometime in the forgotten past discarded and never replaced. Despite our ignorance about these matters, our outside lavatories were called “The Pots”. At a call of nature we mounted the wooden pot supports to bare our bottoms and let go through the roundels, but when the icy blasts of winter blowing through the roundels caused goose pimples and chattering teeth we used the floor until the underfoot conditions forced us to use the open-air compound behind the cubicles. There was no water supply there from any pipe or stream, and no wipes of any kind were available to us; only the falling rains washed the place. When we left the play hall for a call of nature on a rainy wintry night we had to negotiate through the slurry in the unlit lavatory compound; when we returned with soiled clogs we exuded a mighty stench. Once every fortnight Jer the farm labourer shovelled the human waste into a cart, and as the load was pulled by Ned, the institution’s donkey, through the precincts, the pong forced us all to turn away in disgust. Father McCarthy deemed in 1945 that the appearance of our outside lavatories was an eyesore to visitors and ordered the building of a six-foot-high concrete wall, and in doing so he concealed the perfect conditions for a cholera epidemic that could have wiped us off the face of the earth.

(Alfred O’Mahony, The Way We Were Inspire Books, Skibbereen 2011)

It’s probably a good thing that no part of the former Fishery School and National School remains today: the site has been completely redeveloped (above). There is a memorial, a simple carved granite stone which leaves a whole lot unsaid. What makes me shiver is the fact that this maltreatment happened not in the Victorian era of child labour – grotesque and inhumane conditions such as those which Charles Dickens vehemently campaigned to highlight and eradicate in the middle of the nineteenth century – but in my own lifetime.

Email link is under 'more' button.

Here and there ancient field fences poked their way out of the heather, while skylarks warned of our approach and standing stones framed a distant view.

Here and there ancient field fences poked their way out of the heather, while skylarks warned of our approach and standing stones framed a distant view.

On day 2 we decided to make the climb to the Cape Clear Passage Grave – but I will let Robert tell that story and content myself with saying that I hope he tells you all how arduous the climb was, and how thick the gorse, so you can see how I suffer for science.

On day 2 we decided to make the climb to the Cape Clear Passage Grave – but I will let Robert tell that story and content myself with saying that I hope he tells you all how arduous the climb was, and how thick the gorse, so you can see how I suffer for science.