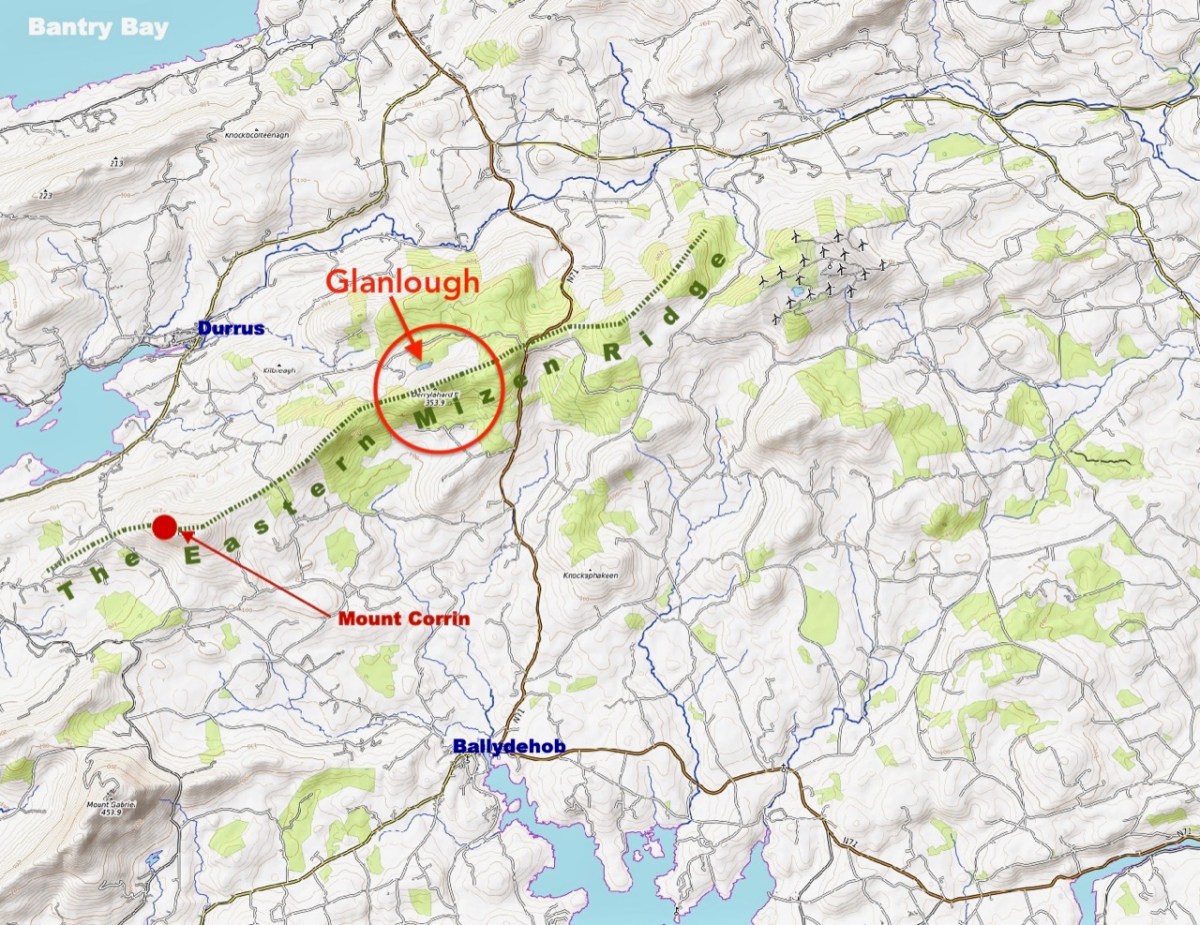

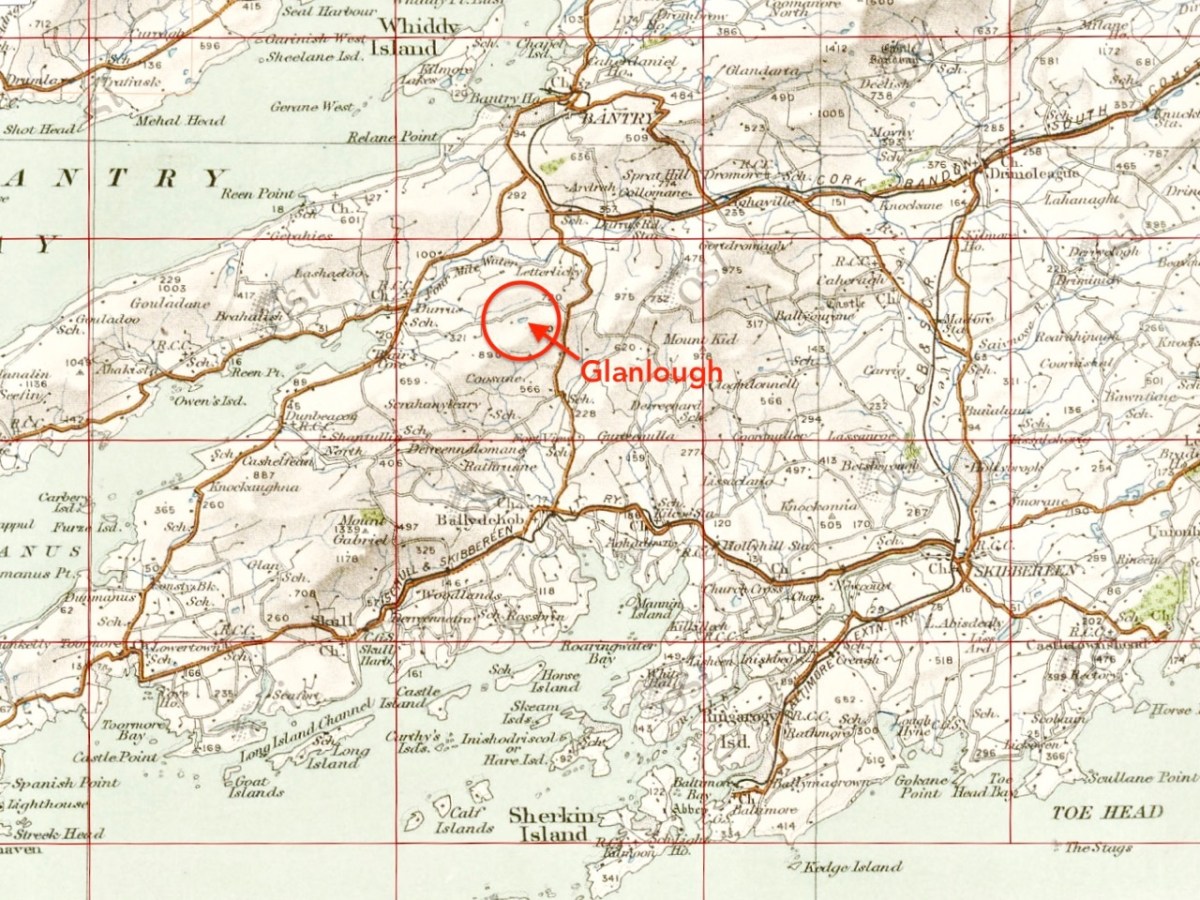

The peak of Derrylahard East is perplexing. It’s on a continuation of the Eastern Mizen Ridge that runs from just west of Mount Corrin (which we visited exactly a year ago), takes in Letterlickey Cairn (ditto) and peters out close to the wind farm at Ballybane West (which we explored last October). At its highest point it overlooks Glanlough (from the Irish Gleann Locha – ‘Glen’ or ‘Meadow’ of the lake). We must not be confused or misled by another Glanlough nearby – on the Sheep’s Head peninsula, nor yet another in Co Kerry.

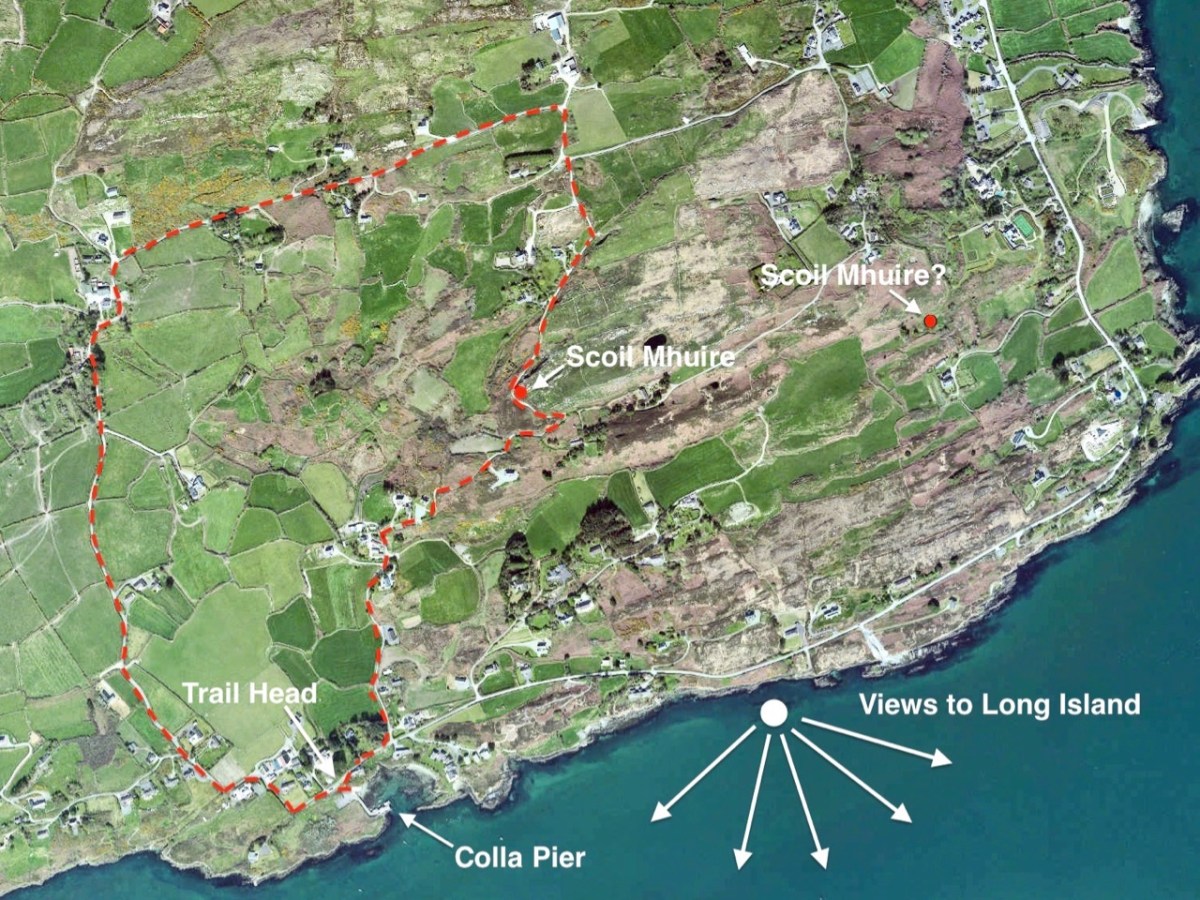

On the map above I have indicated Glanlough, which is central to our most recent peregrination. It is a mountain lake which has been virtually hidden over the last decades by thick commercial pine forests. Very recently, much of the forest has been felled, and views from the top of the ridge are now revealed: they are magnificent and far-reaching. In fact, from the high point we found we could see the 12 arched bridge at Ballydehob – which means. of course, that we can also see Derrylahard East from our own village.

The upper picture was taken from the Derrylahard East Peak with a lens stretched well beyond its limit, but you can see the 12 arched bridge and the sandboat quay house just below the centre of the view: Cape Clear is on the horizon. The lower picture was taken a while ago from the 12 arched bridge in Ballydehob, looking north towards the Derrylahard East Peak, which is swathed in cloud to the left of the rainbow.

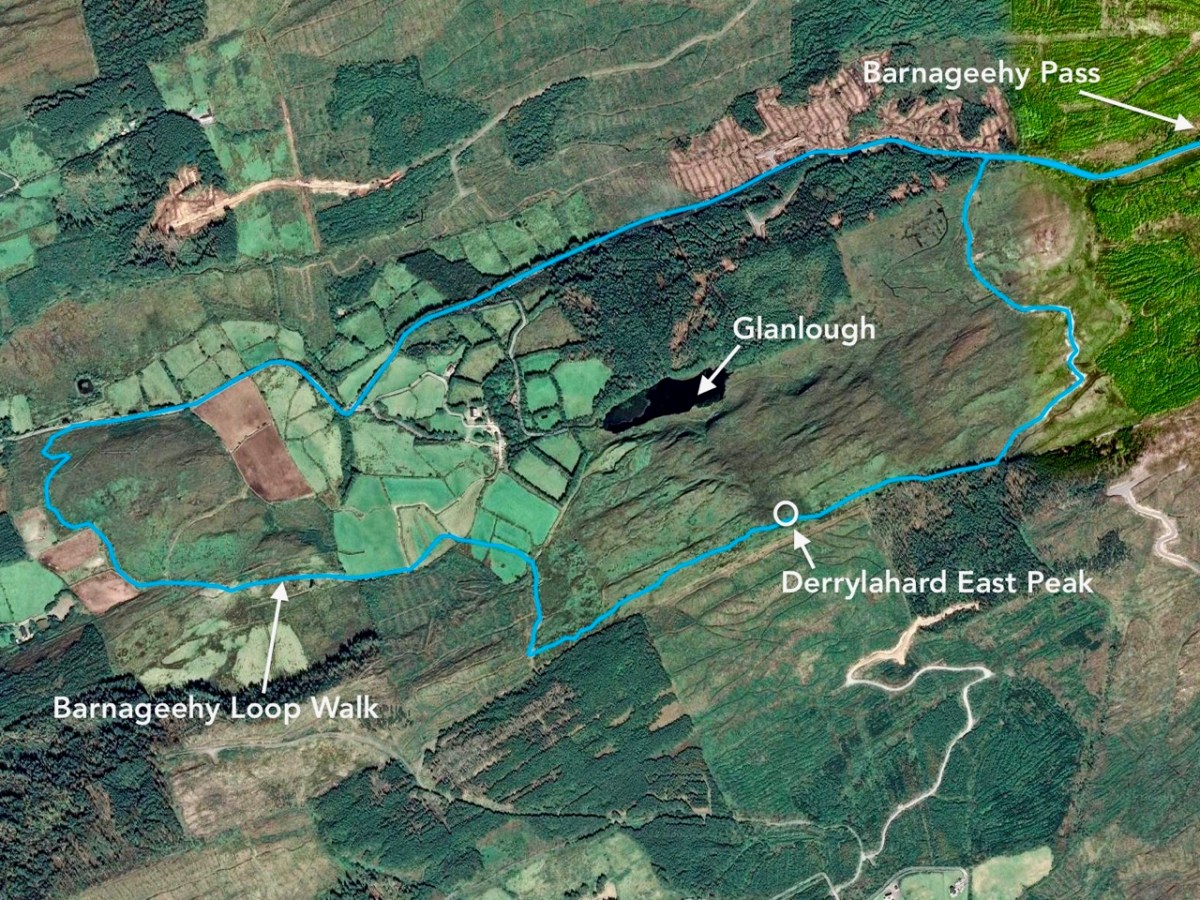

We started the walk at the western end of the loop: we accessed it from a road that runs through the forestry from Barnageehy down to Durrus. As we gained the higher ground we could see the ridge path that would lead west through to Mount Corrin – currently closed due to storm damage. We turned uphill and kept close to the townland boundary. Below – Finola is correctly negotiating the stile by going backwards down the steps!

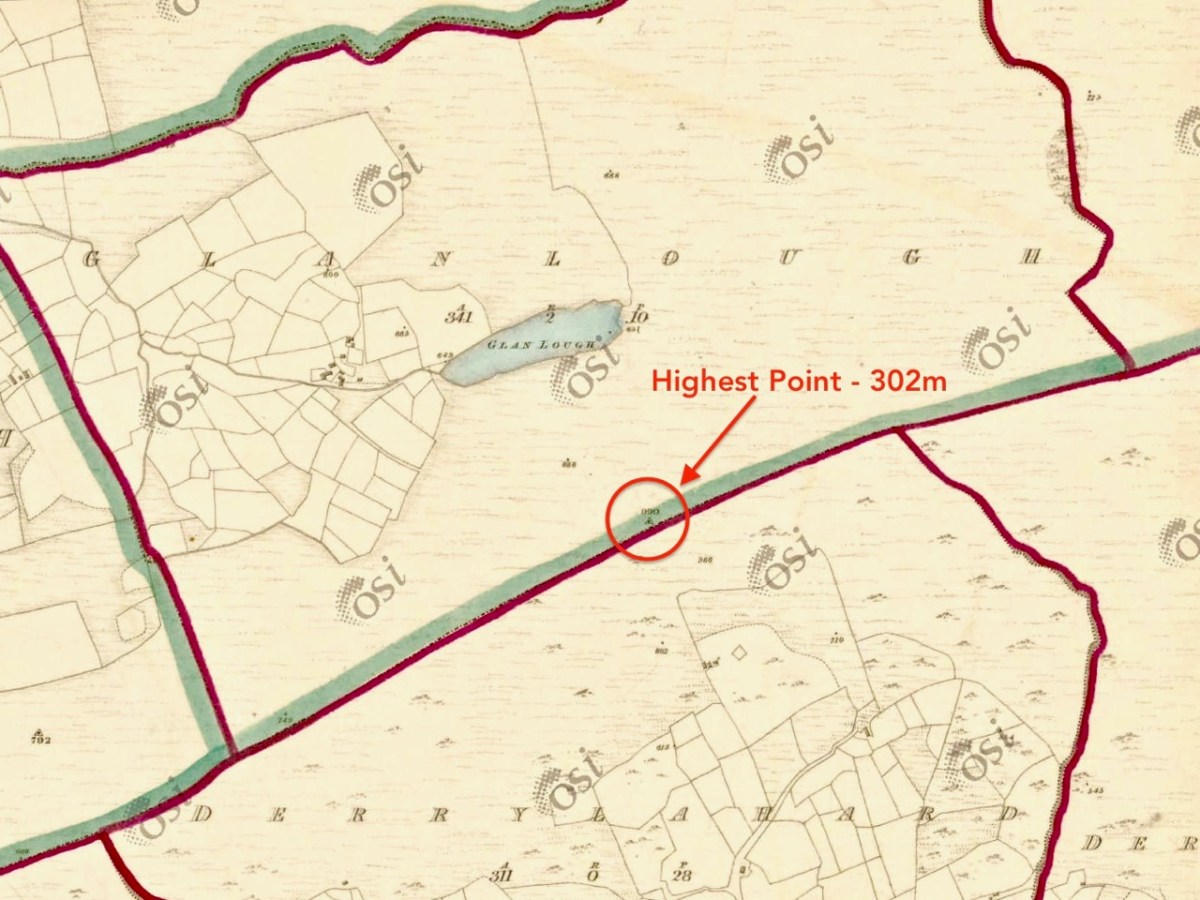

We followed the Sheep’s Head Barnageehy Loop Walk in an anti clockwise direction, circling the lake of Glanlough and looking out for the summit, which is known as Derrylahard East Peak, even though it appears to be within the townland of Glanlough. According to the 6″ OS map, which dates from the 1840s, there was once a trig point at this summit: a height of 990ft – 302 metres.

At the peak: Finola looking back towards Gabriel – always dominating the landscapes in West Cork – with the islands and ocean in the distance; Dunmanus Bay and the Sheep’s Head to the west, with the Beara Peninsula visible beyond; the view east encompassing the Ballybane West turbines and Mount Kidd.

Upper map: the 1904 OS showing Glanlough lake in context with the wider topography of West Cork. Above – the Down Survey, made between 1656 and 1658: this section covers the area shown in the OS above it, and is at a comparable scale. The red asterisk shows the position of the lake at Glanlough: I had hoped there might be some notation on the Down Survey that would give some insight into the name of Glanlough, but the old map is fascinating for the fact that very few of the names are familiar to us and barely a scattering of them can be easily equated with place names today.

I said at the outset that the peak of Derrylahard East is perplexing. For one thing, it is clearly in the townland of Glanlough, yet bears the name of the neighbouring townland. Then there is the altitude of the summit: mountainviews.ie shows two figures for the height above sea level: 301m (which I would – almost – agree with), but also the figure of 353.9m, which must be a mistake. Unless, of course, there is something preternatural in this small patch of West Cork territory: I’m thinking of the legend of the ‘floating’ islands in the lake on Mount Gabriel. According to John Abraham Jagoe, Vicar of Cape Clear – from the Church of Ireland Magazine 1826 – they ‘…float about up and down, east and north and south; but every Lady-day they come floating to the western point, and there they lie fixed under the crag that holds the track of the Angel’s foot…’ Perhaps our peak fluctuates at will to confuse us? The shape of the summit is also intriguing: we sensed there are traces of a circular platform and a number of loosely scattered stones – could there have been a megalithic structure here?

The views from this peak would justify it being marked out as a special site, and we could expect to find some stories recorded in the folklore archives, but no: the Duchas Schools Collections reveals nothing of the peak, the lake, nor the townland.

As we descended the track we were grateful that the recent forestry removal has opened up the extensive views to the south, over Roaringwater Bay, but we are also reminded of the devastation that this type of monoculture creates. The scarring of the landscape will last for years, until eventually covered by further spruce planting: then the views will vanish again.

As we left behind the havoc of the ravaged hillsides it was good to find some pastoral prospects, reminding us that West Cork always has unfolding delights and juxtapositions, wherever we wander.

Previous posts in this series:

Knockaphuca, Corrin, Letterlicky Cairn, Lisheennacreagh, Knockatassonig