First Vatican Council

The Protestant Evangelical Crusade of the first half of the nineteenth century in Ireland was able to gain traction for two reasons. First, the Catholic Church, after centuries of suppression, was impoverished and underserved. While over 80 percent of the population was Catholic, there were relatively few priests, no seminaries to train new ones, no institutions of higher learning, few churches fit for purpose, few Catholic resources in Irish (the language of the people), and little access to primary education. Second, for the majority of the rural population, actual religious performance revolved not around church, mass and the sacraments, but around a variety of folk practices such as patterns at holy wells, stations, wakes, funerals and pilgrimages – events which started off with penitential prayers and offerings and often ended in drunkenness, revelry and even faction fights. Religious belief, meanwhile, was based on centuries of folklore, mythology and superstition mixed up with religion, so that saints and giants, pookas and devils, banshees and miracles, all became part of a rich melting pot of stories to underpin everyday behaviours.

Some of the main resources I consulted for this series. All excellent reading, and towering over them all is Patrick Hickey’s meticulously researched study of the Famine in West Cork

During the course of the nineteenth century all of that was to change. The first half of the century saw significant advances. Catholic Emancipation in 1829, the establishment of the National School System in 1931 (soon dominated by, and ultimately controlled by the Catholics) and the Tithe Wars of the 1840s all galvanised the Catholic population into a new assertiveness. Many new churches were built in West Cork, mainly plain, barn-style buildings which were nevertheless a great advance on tumble-down mass houses or the open air, and some of which are still in daily use.

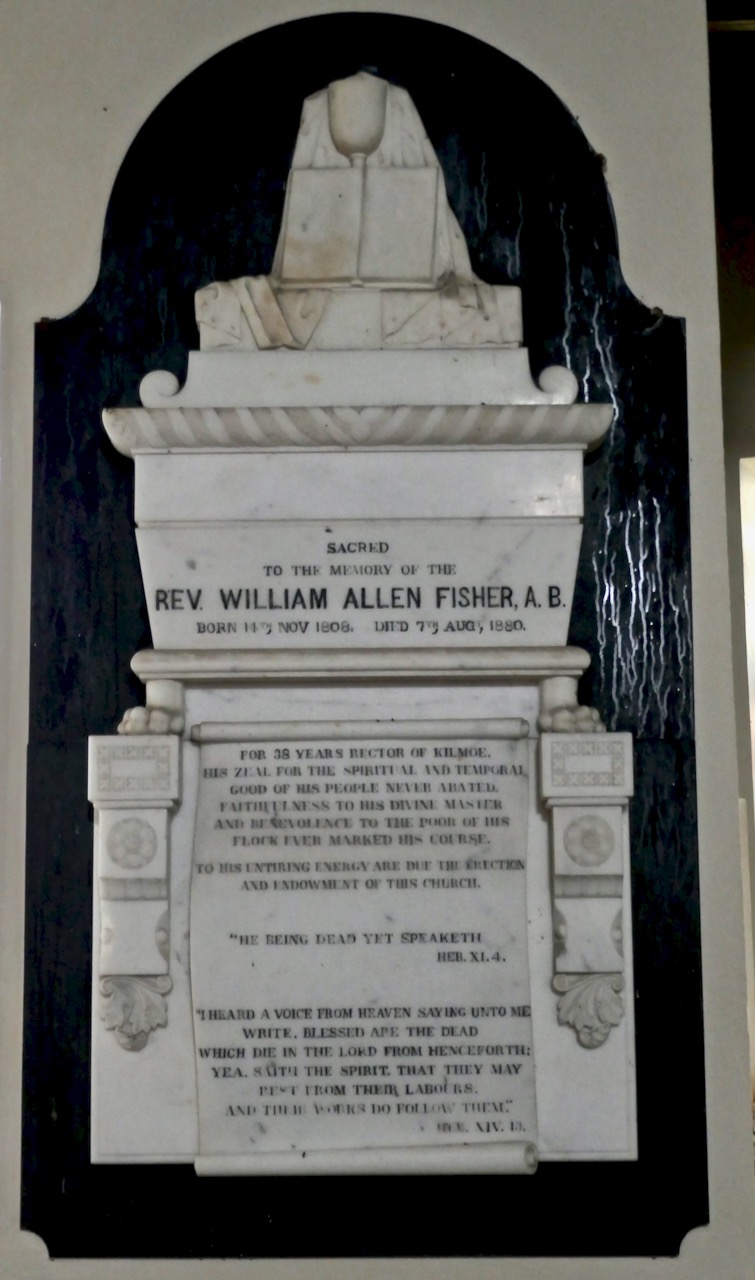

And then Ireland was struck by The Great Hunger. Over the ten years from 1841 to 1851 one in every four people in Cork died or left. Proportionately, of course, the poorer and more remote districts were hit the hardest. In the maelstrom of disaster, Catholic priests and Protestant Clergymen worked to alleviate the situation for their flock often together but sometimes, disastrously, in opposition to each other, as with the Rev Fisher in Kilmoe, and the ‘colonies’ in Dingle and Achill, leading to enormous resentment about ‘souperism’ but also to panic among the Catholic hierarchy about the inroads that the evangelicals had managed to make.

Archbishop John McHale of Tuam, Gallican and fiercely nationalist: Cullen disapproved of him (image licensed under Creative Commons, Attribution: Andreas F. Borchert)

Enter the towering figure of Paul Cullen, Archbishop and later Cardinal, who was to dominate Irish Catholicism from his arrival as Archbishop of Armagh in 1849 to his death in 1878. According to Bowen, because of the increasingly Gallican attitudes of MacHale and his Episcopal supporters and their failure to discipline their clergy or to hold the extension of Protestant authority, the Vatican came to an important decision. The Pope would send to Ireland an ecclesiastic totally committed to the Ultramontane cause, and he would restore order among the faithful. The ecclesiastic who came as papal delegate and Primate was Paul Cullen.

Cardinal Paul Cullen

Gallican, in this context, refers to a philosophy that respects the state in civil matters and religious authority on spiritual matters – a ‘render unto Caesar’ approach to which many Irish priests, trained on the continent, adhered. As Daniel O’Connell expressed it in 1815, I am sincerely a Catholic, but not a Papist.

Cross Keys, The Papal Insignia. This one was spotted in a small Catholic Church in West Cork; look out for it in churches built after 1850.

Ultramontane Catholicism was the opposite – it placed papal authority as central to the conduct of the church and its members. In part, nineteenth century Ultramontanism was a reaction to the horrors of the French Revolution but also to the nationalistic policies of Bismarck which imposed state supervision on church activities. Cullen was an arch-Romanist. In his engaging study Ireland Since 1800: Conflict and Conformity, Theodore Hoppen says, Cullen, one of the towering figures of modern Irish history, had spent virtually all his earlier career in Rome where he had been inoculated against liberalism in its continental form.

Cullen’s first major initiative was the Synod of Thurles in 1850. Hoppen again:

Patterns now stood condemned as potentially immoral. Wakes were to be sanitised and all the other rights of passage – funerals, baptisms, weddings – brought under clerical auspices alone. . .

Before the 1850s were out he had imposed Draconian loyalty oaths upon the staff and insured that both Maynooth and the new Seminary founded for his own diocese at Clonliffe in 1859 were henceforth to produce only priests totally committed, at least in theological and social terms, to his own version of the clerical role. While this did nothing to encourage intellectual endeavour within the church, it proved highly efficacious in producing a steady stream of those dogged pastoral moralists who, armed with the rulebook at once precise and immutable, could alone have furnished the kind of religious justification and guidance which important sections of the laity increasingly demanded and required.

The reference to ‘sections of the laity’ reflects the emergence of a new rural class. All over Ireland population decline after the famine was hastened by mass evictions as landlords took advantage of the situation to consolidate their holdings. In the second half of the century a new class of ‘strong farmers’ emerged who were to become the backbone of rural life. Seeking respectability, conservative, passing on their farms only to the eldest son, finally approaching financially security and land ownership, they supported the hierarchical and puritanical expression of religion represented by this new Catholicism. Cullen came from, and kept in close contact with, this very group.

Pope Pius IX

Cullen was extremely well connected within the Vatican and indeed was a personal friend of Pius IX, still the longest-serving Pope and one of the most centralising and controversial. He could rely on Cullen for support – and needed it to get the infamous doctrine of Papal Infallibility passed at the First Vatican Council in 1868 (that’s my lead image for this post). It outraged not only Protestants but liberal Catholics too – a breed that still clung on to some influence as the century wore on, but were ultimately on the losing end of Irish religious history. Charles Kickham, for example, one of the Fenians and a revered writer, was a constant critic of Cullen’s ultramontane activities. Cullen dismissed him as a cultural Protestant.

Charles Kickham. This image is reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland (with permission)

Others, such as Charles Gavan Duffy, according to Bowen had to flee the kind of Ireland that Cullen had created, where the ‘power of the priest is the one unspeakable, unmentionable thing’. So long as their presence was felt in Irish Catholicism these people were to experience the full force of Cullen’s inquisitorial instincts.

Marian imagery starts to dominate much Catholic Church decoration in this period

It is at this time that the great period of Catholic church building commenced and triumphalist cathedrals and churches were erected all over Ireland, often on the highest piece of ground in the town. ‘Roman’ initiatives such as an emphasis on Marian worship (Cullen helped to usher in the ‘doctrine’ of the Immaculate Conception in 1854), Novenas and Sodalities, ‘Miraculous Medals’ (the Vincentians had distributed these in Kilmoe and they were much derided by the Protestant clergymen) and of course a continuation of the yearly missions or retreats where the faithful were encouraged in their faith (or whipped into line, according to your perspective) by specialist itinerant preachers. Often referred to as Cullen’s Devotional Revolution, forms of worship settled into the pattern we often now consider ‘traditional’ Irish Catholicism.

In this window from Killarney Cathedral a direct parallel is drawn between the baptism of Jesus and the conversion activities of Patrick

Stained glass and statuary of the period is a fascinating mix of the continental (the Italian holy statue factories must have been doing a booming business) and the local, as priests incorporated their own parish and diocesan patron saints into the overall decorative plan. Killarney Cathedral, started in 1842 but interrupted by the Famine, was ready for worship by 1855. Decoration was added as time went by, including a set of windows clearly designed with an Ultramontanist message in mind – they draw clear parallels between Irish saints and martyrs, the life of Christ, and the ultimate authority of Rome. It’s quite a demonstration of verbal and visual sleight of hand, and a powerful message to the congregation.

And in this one the message is direct – look to Rome for spiritual guidance. A message from St Patrick himself

In Kilmoe, Fisher had built his own Church of Ireland church in Goleen in 1843 – the one that is now, for want of parishioners, in use as a sail making workshop. In contrast, the large Catholic ‘Star of the Sea and St Patrick’ Church stands on the hill, dominating the town and is very active. It was built in 1854, only a few years after the devastation of the famine, quite an amazing testament to the resilience of the population and the growth in influence and economic power of the Catholic church.

Goleen with the Catholic Church dominating the skyline

It is also, of course, a reminder that the Church of Ireland was finally disestablished by the Irish Church Act of 1869 under Gladstone.

A typical Punch cartoon, this one showing Gladstone cosying up to the Irish. And of course there’s a pig, potatoes, whiskey and a none-too-subtle reference to Rome – all the tropes of Victorian images of Ireland

This Ultramontanist Catholicism was the church I grew up in, walking up to mass every Sunday in the Holy Redeemer in Bray (built in 1895), going to confession on Saturdays, attending the Children’s retreats and participating in the Corpus Christi parade. Although I knew Protestants because we lived beside them, I had never been in a Protestant church. I attended a national school and an all-girls convent school run by the same order of nuns (the Loreto order) that set up convents all over Ireland in the nineteenth century. It always puzzled me that we called ourselves Catholics but the Protestants always insisted on calling us Roman Catholics. I understand why, now.

This is it, the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer in Bray – note the sodality banners and the extreme ornamentation. It’s much plainer now, having been toned down considerably in the post-Vatican II era. (This image is reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland, with permission)

I’ve learned a lot about my own history in the course of this series and about the kind of attitudes I grew up with (and which, if I am to be perfectly honest, can still stir inside me in certain circumstances, despite the fact that I am now a non-believer). I suppose awareness of our history and constant vigilance against ingrained prejudice and facile assumptions has to be our watchword if we are not to perpetuate the mistakes and schisms of the past.

It’s worth enlarging this extraordinary print and having a good look. It’s an address to Cardinal Cullen, enumerating his many achievements. I love the bottom right image of him defeating the dragon. What evil does this dragon represent? I think you can choose one of several candidates. (This image is reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland, with permission)

And what conclusions have I come to about Fisher – was he a Saint or a Souper? He was both. He worked incredibly hard and succeeded in saving hundreds, Catholic and Protestant, from the worst ravages of the Famine, and he died of famine fever himself. But his enthusiasm for his own narrow definition of Christianity drove him to alienate his Catholic counterparts by seeing the Famine as God’s punishment on Romanist intransigence, and to conflate the need to save bodies with the imperative to save souls.

Fisher’s gravestone, in Mount Jerome, Dublin. I am not sure why he would have been buried there, since he died, I think, in West Cork. Perhaps he is simply commemorated on this stone, on the grave of his brother and sister-in-law (© IGP Archives)

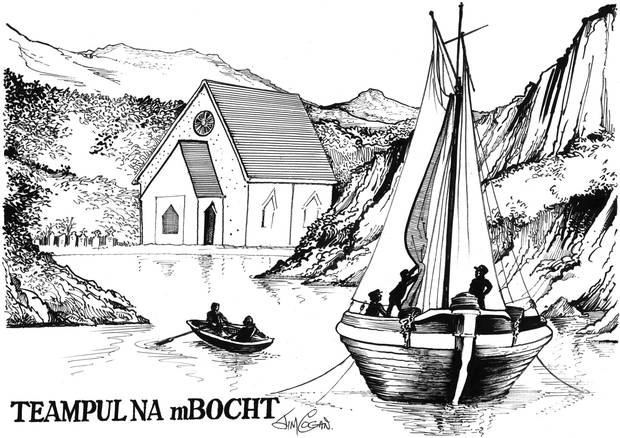

I am left with an abiding sense of sadness that the events of the mid-nineteenth century, as symbolised for me by the story of Teampall na mBocht, have left a legacy of sectarian division in Ireland. Perhaps now we can leave Fisher – and all the other crusaders and reformists and counter-reformists – to lie in peace.

A reminder, in one of the Killarney windows, that Patrick was sent by the Pope

I’d like to end with the words of Carlo Gébler, reviewing John Kelly’s excellent book on the Famine, The Graves are Walking:

It’s tempting, with figures as obdurate and flawed as Trevelyan, to judge them by our standards and find them guilty of crimes against humanity – but. . . be advised: Kelly has no truck with this type of transaction. On the contrary, as he firmly but politely reminds us at every turn, all the participants in this miserable saga were made what they were by their period, should be judged only by standards of their time, and, however, we might wish it weren’t true, did believe they were doing right.

None of this is easy to accept, but part of growing up as a country is that we allow those we hold responsible for our woes the integrity of their beliefs, no matter the suffering they caused.

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7