A personal selection of photographs, taken in West Cork in 2022, by Robert and Finola.

Looking forward to sharing many more adventures with you in 2023.

A personal selection of photographs, taken in West Cork in 2022, by Robert and Finola.

Looking forward to sharing many more adventures with you in 2023.

Last week’s post The Twelve Arches of Ballydehob proved a most popular subject. Ballydehob’s railway viaduct – dating from the late nineteenth century can’t be ignored. It was fairly easy to put together another dozen pics of the structure, making a good Christmas Day theme to take your minds off turkey and stuffing!

As we have lived not too far from the viaduct over the last ten years, we have seen it – and photographed it – in many of its moods. And it’s a constant backdrop, of course, to life in our West Cork village. Below – here it is, supporting a very ancient tradition, on St Stephen’s Day (that’s me on the right!):

“No Wrens Were Harmed in the Making of this Post!” That was the title of my RWJ article on the Wren Day festivities in Ballydehob in 2019 – pre-Covid. It was great to be out and about in the village, echoing a custom which has been passed from generation to generation. When I grew up in England I joined in the Mummers’ tradition there: I followed it for much of a lifetime, and even now can recite the whole play without a prompt… “Here comes I, Bold Trim Tram: Left hand, press gang – press all you bold fellows to sea…”

Something else which could do with a revival is the Pedalo tradition. Pedalos were brought out of storage for an unique occasion in the summer – a project named Inbhear, an art installation by Muireann Levis. Here is own my post about it.

I was pleased to have this photo of the viaduct in my collection. If the scale looks a little wobbly it could be because this – and the train – are models sited at the West Cork Model Railway Village at Clonakilty. Below – a local company, in Ballydehob, has chosen to use the bridge in its title.

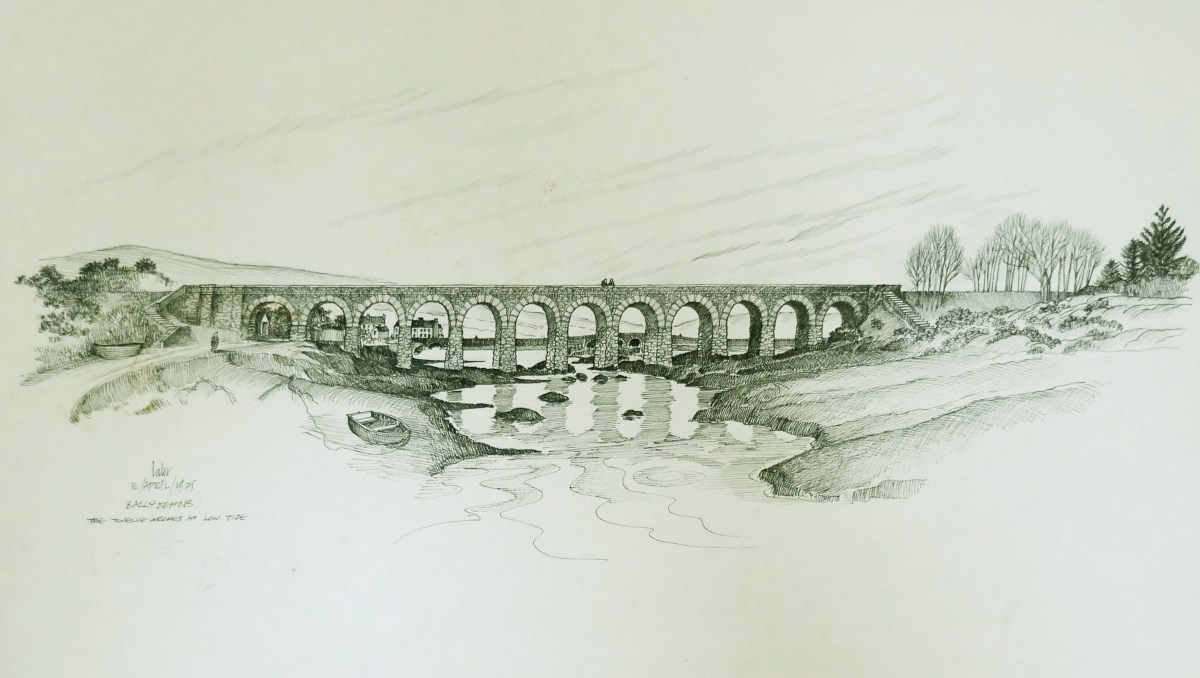

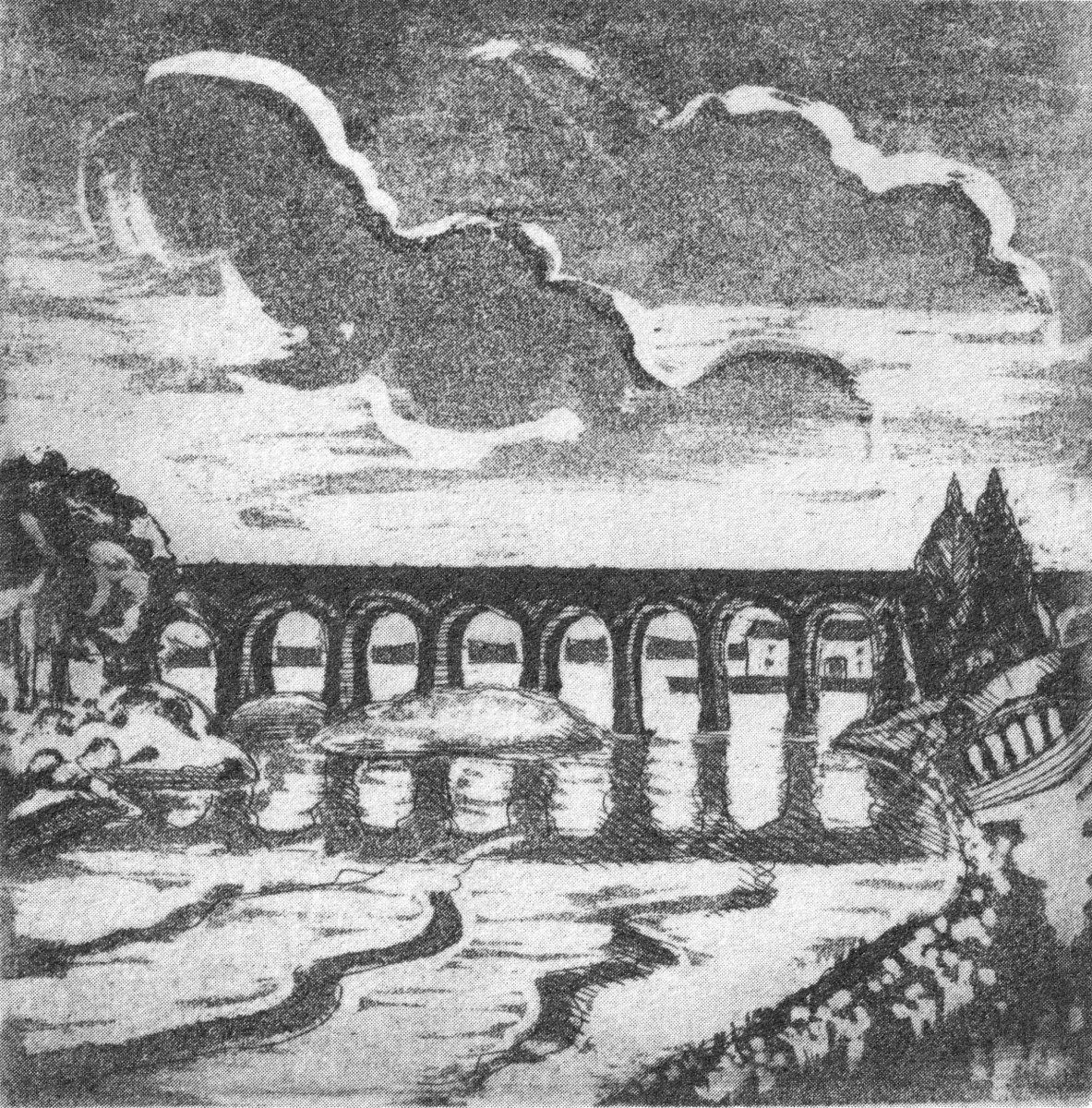

We showed you some of Brian Lalor’s work last week. Here’s another of his drawings. It is dated 1975: he tells me he has plenty more viaduct pics if I write another post in the future.

Atmospherics a-plenty: we have them all the time in Ballydehob. We do live in one of this world’s most inspiring places… Have a very good and atmospheric Christmas, everyone! And – safe journeying if you are out and about.

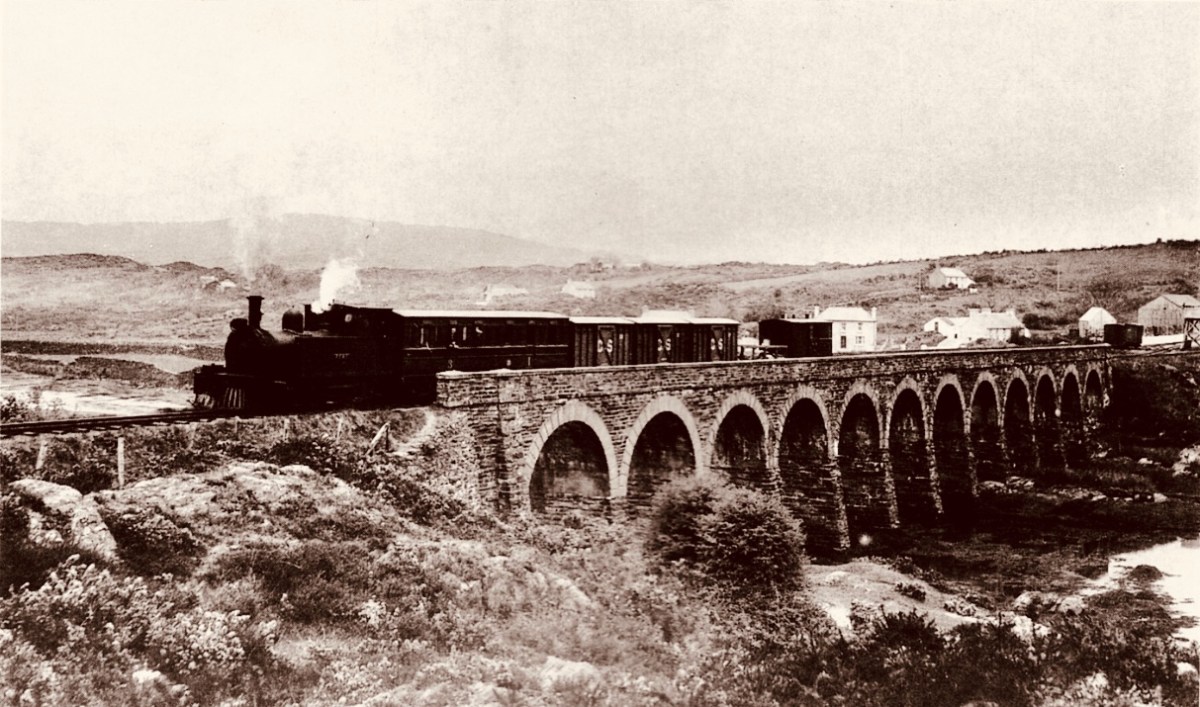

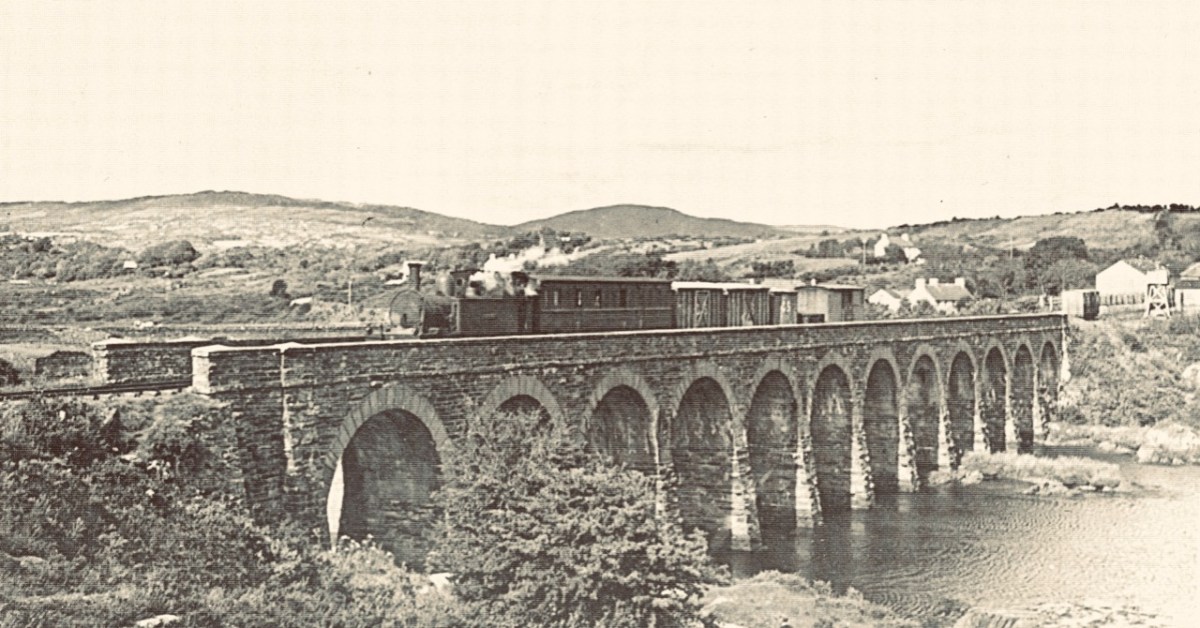

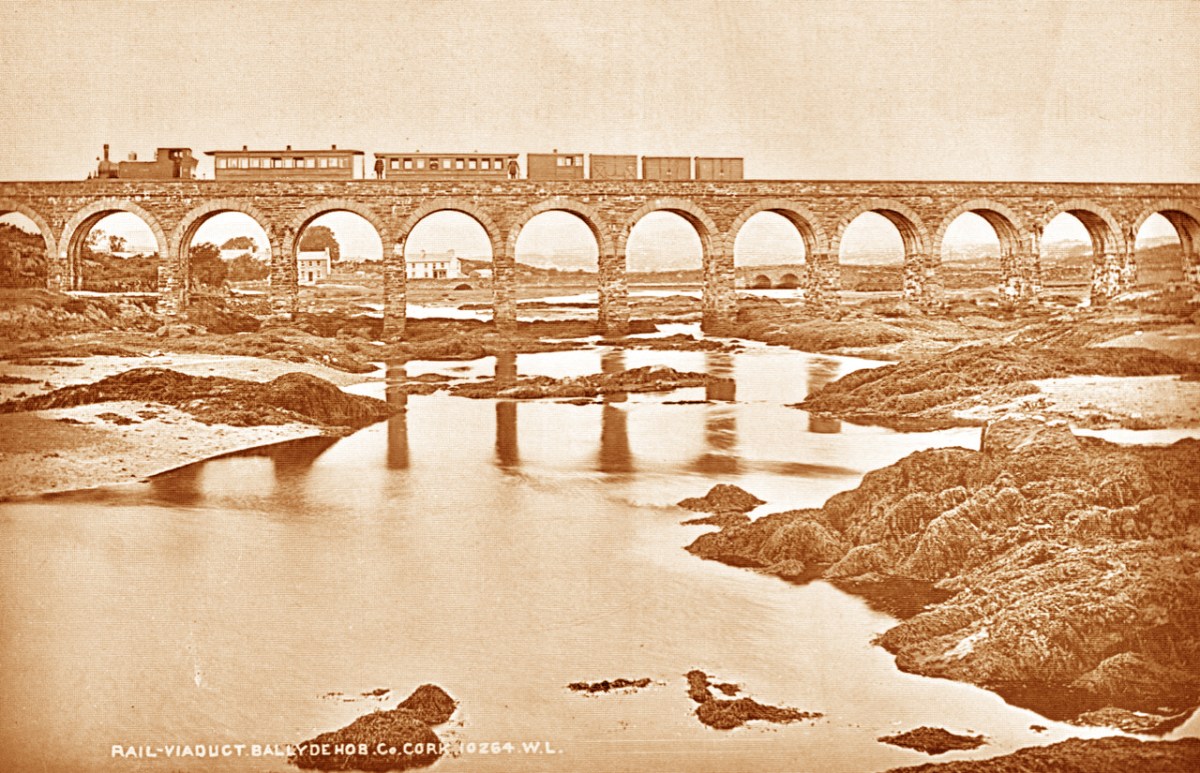

As we are approaching the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas I thought it fitting to give you Twelve views of Ballydehob’s iconic viaduct. Our West Cork village of Ballydehob has many claims to fame. It has been the centre of a great Irish art movement in the mid-twentieth century (have a look at this site). But earlier – between 1886 and 1947 – it was an important stop on the Schull & Skibbereen Tramway. This was a three-foot gauge railway line which must have been a great wonder to those who witnessed it in its heyday. There are fragments of it still to be seen, but its most monumental structure remains with us: the twelve-arched viaduct at Ballydehob.

Above: Brian Lalor was one of the creatives who settled in Ballydehob back in the artists’ heyday (he is still here today). The railway viaduct was a great source of visual inspiration to him and to his artist colleagues.

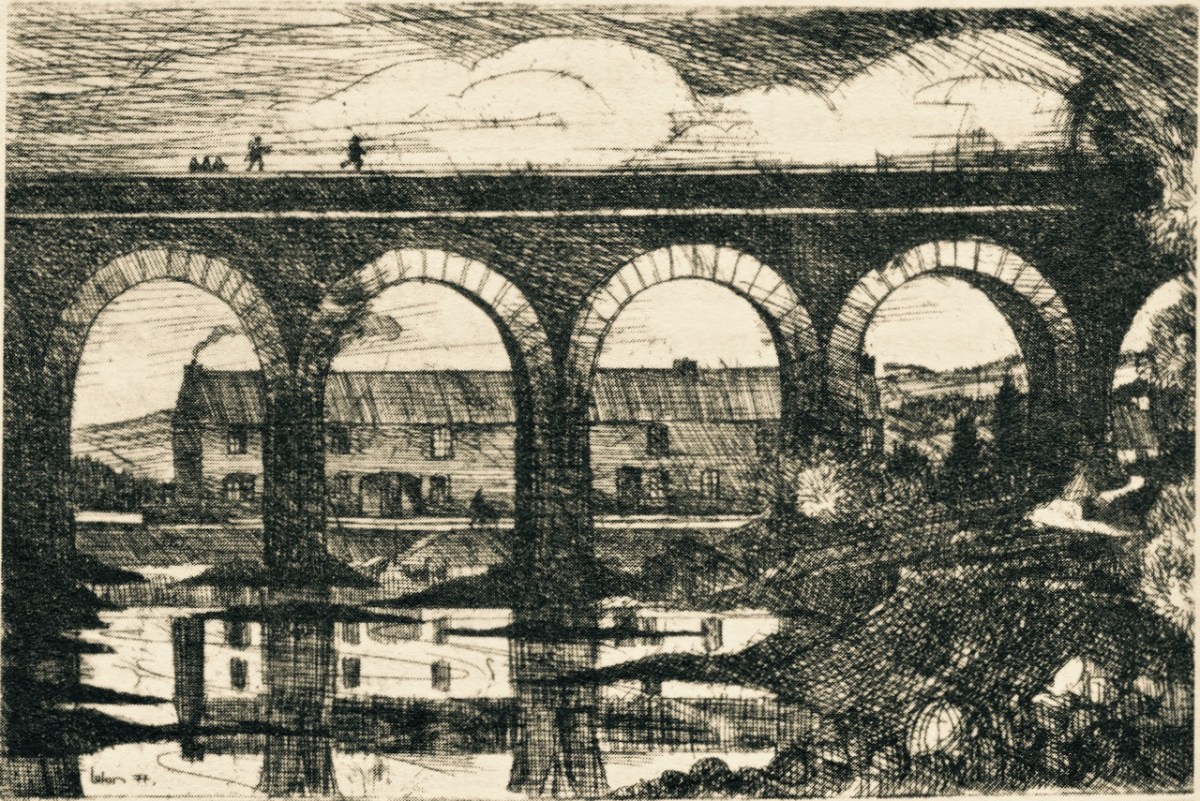

Here (above) is another Lalor work depicting the viaduct (many thanks, Brian). Behind the arches in this print you can see the former commercial buildings on the wharf, now converted to private use. At first glance you might think what a fine masonry structure this is. In fact, most of it is mass concrete. Look at the close-up view of the arches below: they are cast and faced in concrete, albeit the arch-stones are made to look like masonry. Only the facing infills and the parapets are actually of stone. This is quite an innovative construction for its time. Barring earthquake it’s certain to endure.

I was not surprised to find how often images of this engineering feat have inspired artists and others working in creative fields. Here’s a particularly fine example from the days of the artist settlement around the village in the mid-twentieth century (below): this one is a batik by Nora Golden.

I really like this moody photograph by Finola: it demonstrates the elemental nature which repetition and shadow gives to the scene. (Below): we have to see the way over the top, now a public footpath. The railway was a single track narrow-gauge at this point.

The ‘Tiny Ireland’ creator – Anke – has sketched this wonderful caricature of our wharf area, showing the 12-arched bridge in context. Finola has written about Anke. You can buy your own piece of Tiny Ireland through her website, here.

How better to look at the bridge in context than this view from Aerial Photographer Tom Vaughan. Thank you, Tom, for allowing us to use this magnificent image. Here’s the link to his own website. You will find excellent gifts for the connoisseur here. The last of our ‘Twelve Arches’ (for now) has to show us the bridge in its rightful use. I think this postcard – from the Lawrence Archive -dates from the early 1900s. I can’t resist quoting the caption for the rail buffs among you!

. . . A Schull-bound train has stopped especially for the photographer: this is Ballydehob viaduct looking north. The train comprises GABRIEL, bogie coaches Nos 5 and &, brake vans Nos 31, 32 and 38 . . .

The Schull & Skibbereen Railway – James I C Boyd – Oakwood Press 1999

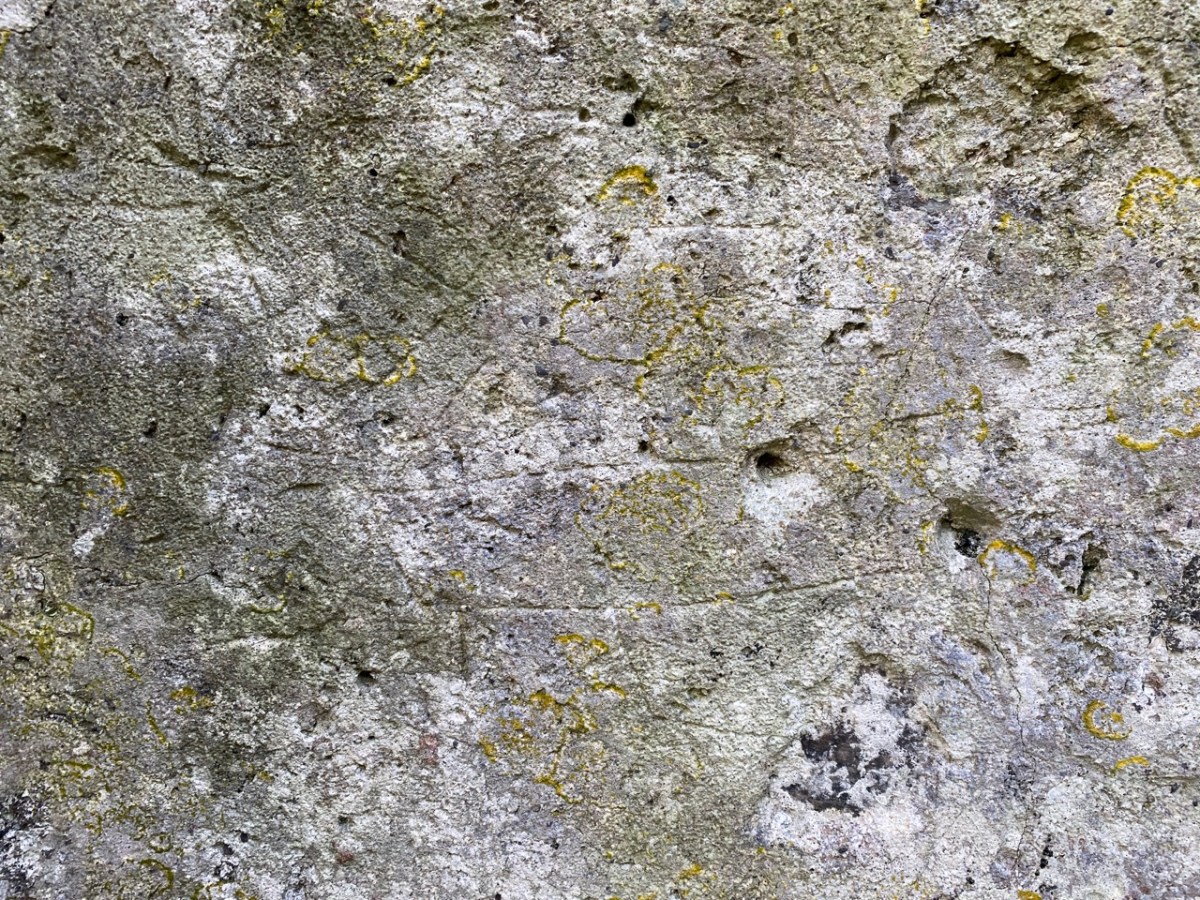

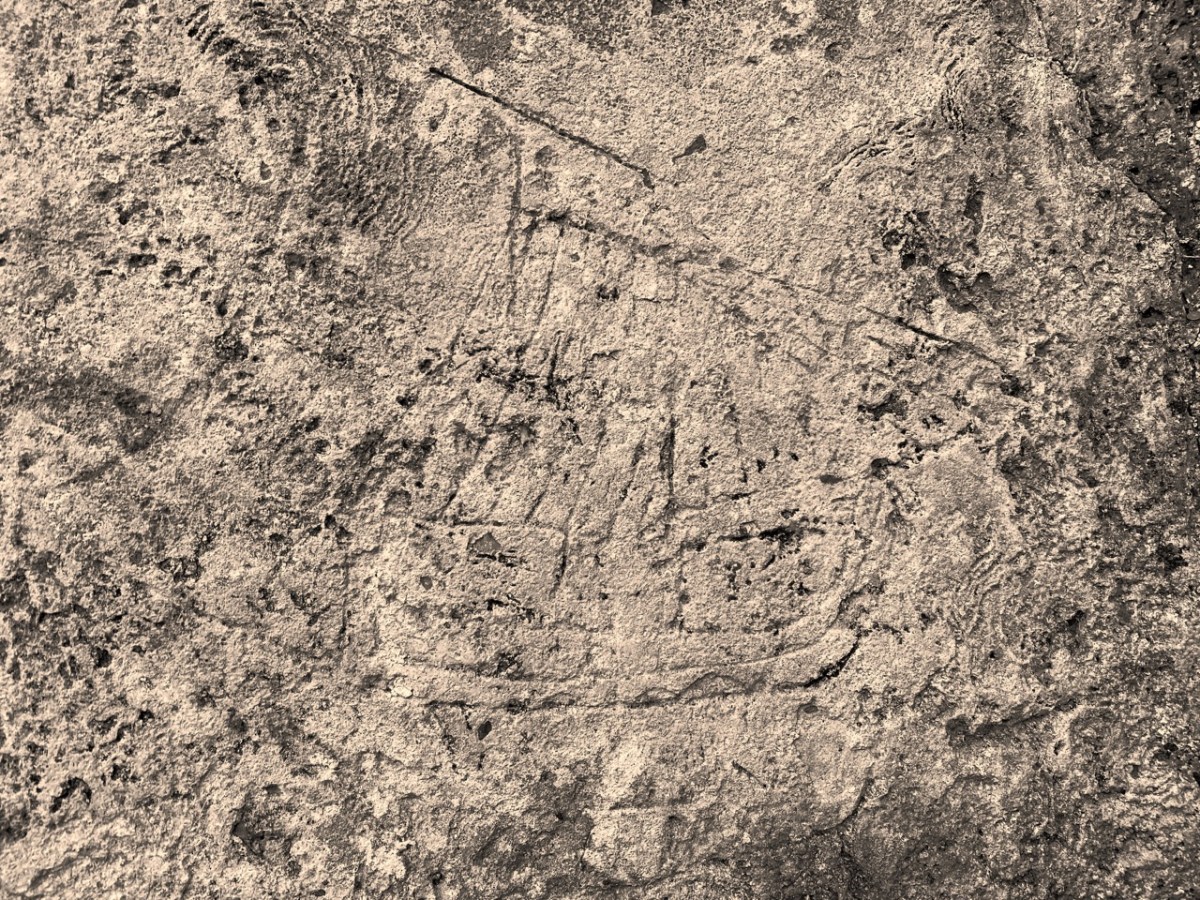

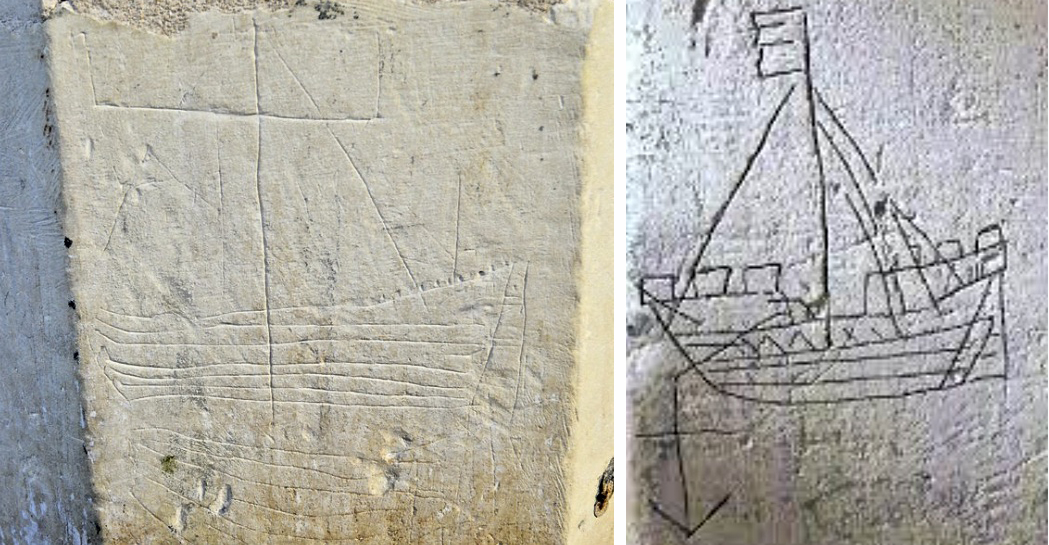

You’ll have to look carefully at the photo above. It’s inside the ruined church which stands in St Mary’s graveyard, Colla Road, Schull.

Here’s the church – a view taken a day or two ago, in a spell of clear, cold weather. It has a fascinating history, which you can read here. Go in through the old main entrance, and immediately look to the wall on your right. Scratched into the plaster there is the ship image. But it’s not the only one.

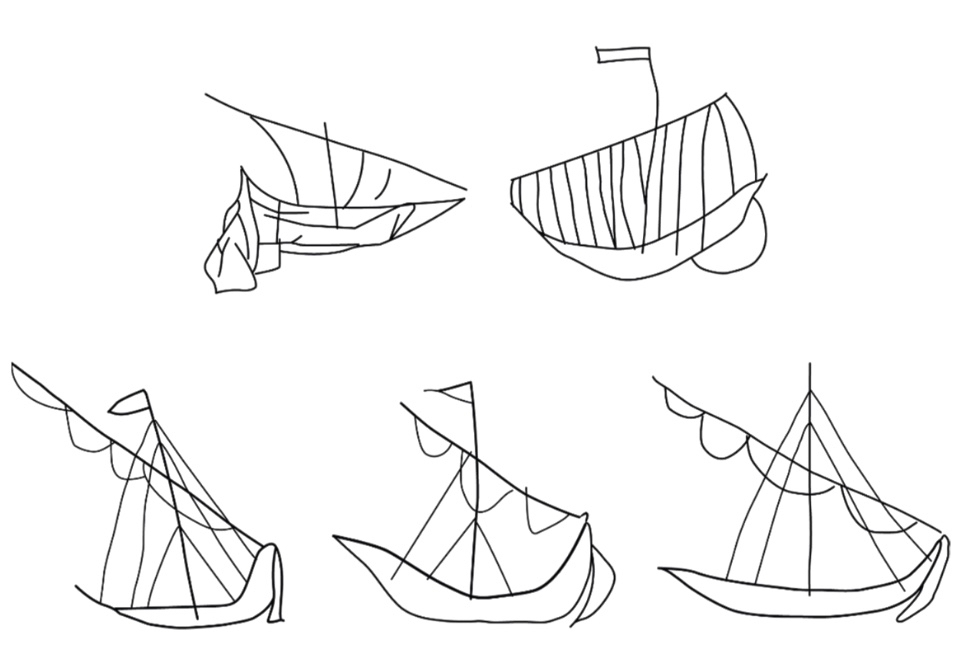

There are more ship images visible on this porch wall; the first – shown in the header – is the most clearly defined. Here are more detailed views of others (I have counted five in total), including further examples on the opposite wall. There may once have been more.

Of course, we would like to know the story of these carvings: who made them? When? And why? As to the ‘when’ we have to sift through the history of the building, although what is known is somewhat fragmentary. One record states that what we see today was built in 1720, but there must have been something there before that, as there is an ogival window in the north-eastern part of the building which is thought to be fifteenth century, and some further architectural features which suggest an even earlier construction:

The north porch – where the ship scribings are – is likely to date from the early eighteenth century, so the ships could not be any older than this. They could have been drawn any time, perhaps, over three hundred years – but are most likely to have been from the earlier part of that period. It has even been suggested that they could have been made by the craftsmen who rendered the walls. Interestingly, ‘graffiti’ which shows ships in churches is not uncommon: there are further instances in Ireland, Britain, and other parts of the Christianised world. The following were traced from St Spas church, Nessebar, Bulgaria. They are possibly the closest examples I have found so far that resemble our main Schull scribing. Interestingly, only one is shown in ‘full sail’. Most examples of this type of graffiti show the vessels without sails, or with the sails furled. Our Schull example is undoubtedly under full sail – and this makes it rare. I attach a further image below the Bulgarian scribings: I have tried to enhance the contrast of the photograph.

What about ‘Who Made Them’? We don’t have an answer to that. We must remember that the Schull examples are a very small part of a very widespread phenomenon and, as I mentioned, there have been suggestions that the ships were a deliberate part of the construction process of the churches: they might have been drawn by the plasterers themselves. Masons left behind their own ‘marks’ on stone walls, ever since medieval times. A British project was started in 2010 to survey all types of ‘informal’ marking on stone and plaster found specifically in Norfolk.

These stone inscribed Masons’ marks are from the Norfolk survey. Below – from the same source – two images of ship graffiti from Cley-on-Sea, Norfolk:

Where do we go from here in our little review of this strange find in Schull? Well, it’s worth noting that these are not the only ‘ships in churches’ image that we find in the corpus of European-wide church architecture. I often remember going into churches and noticing model replicas of ships hanging from the ceiling! I don’t remember seeing such a thing in Ireland, but certainly in Britain and Scandinavia. Here is one from Denmark:

Strangely, I have never looked for an explanation of these. When you start reading about them, it is suggested that they are always in churches which are associated with the sea and with maritime communities, and the church models are seen as prophylactic votive offerings: representing and honouring the ships that the community sail in will prevent them from coming to harm. That begins to make sense, as does the idea that the plaster ship graffiti is also, perhaps, a preventative measure against disaster or ill-fortune.

That theory could be presented as a strong likelihood for finding ship graffiti in churches – but there’s a problem. There are as many examples of ship graffiti in churches which are located far inland as there are on or close by the coast. If you would like my own opinion on this whole quandary, take a look at the photo of Schull church, above. It is built on a mound, perhaps natural but maybe not, with its east wall facing outwards like a ship’s prow. Could there be a far wider symbolism in all this when it comes to the nature of a church building? Is it a stone representation of a vessel, captained by priest or parson, and crewed by the faithful of the community? A final thought on this: when you go into the main body of a church, you enter the Nave. Definition of a nave:

. . . The name of the main public area of the church, the nave, was derived directly from the Latin word navis, meaning ‘ship’ or ‘vessel’, and references dating back to the very earliest days of the Christian church direct that a church should be built ‘long . . . so it will be like a ship’ . . .

MATTHEW CHAMPION – MEDIEVAL SHIP GRAFFITI IN ENGLISH CHURCHES, 2015

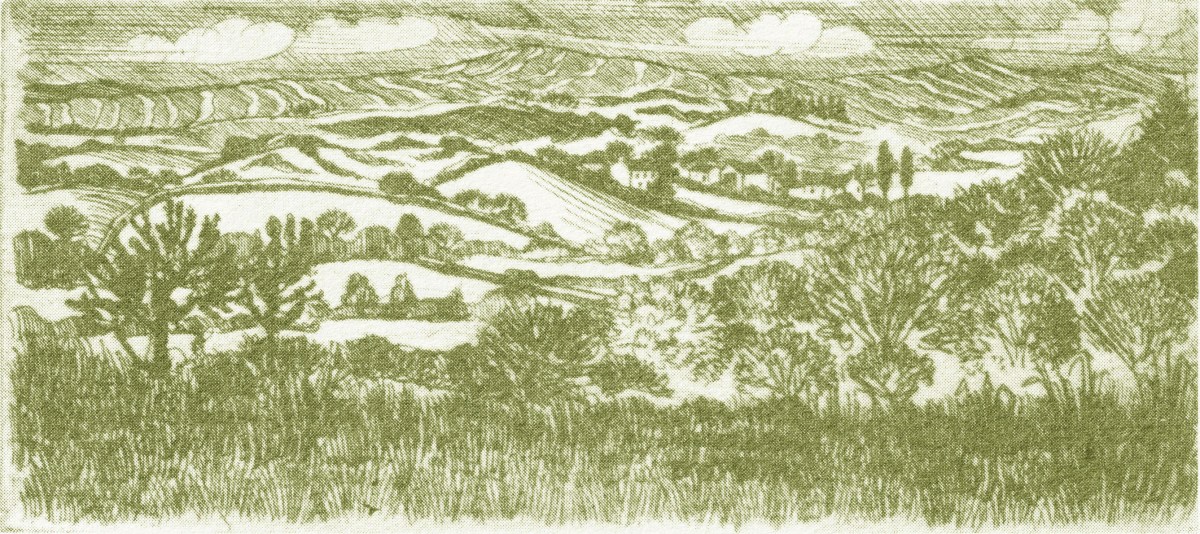

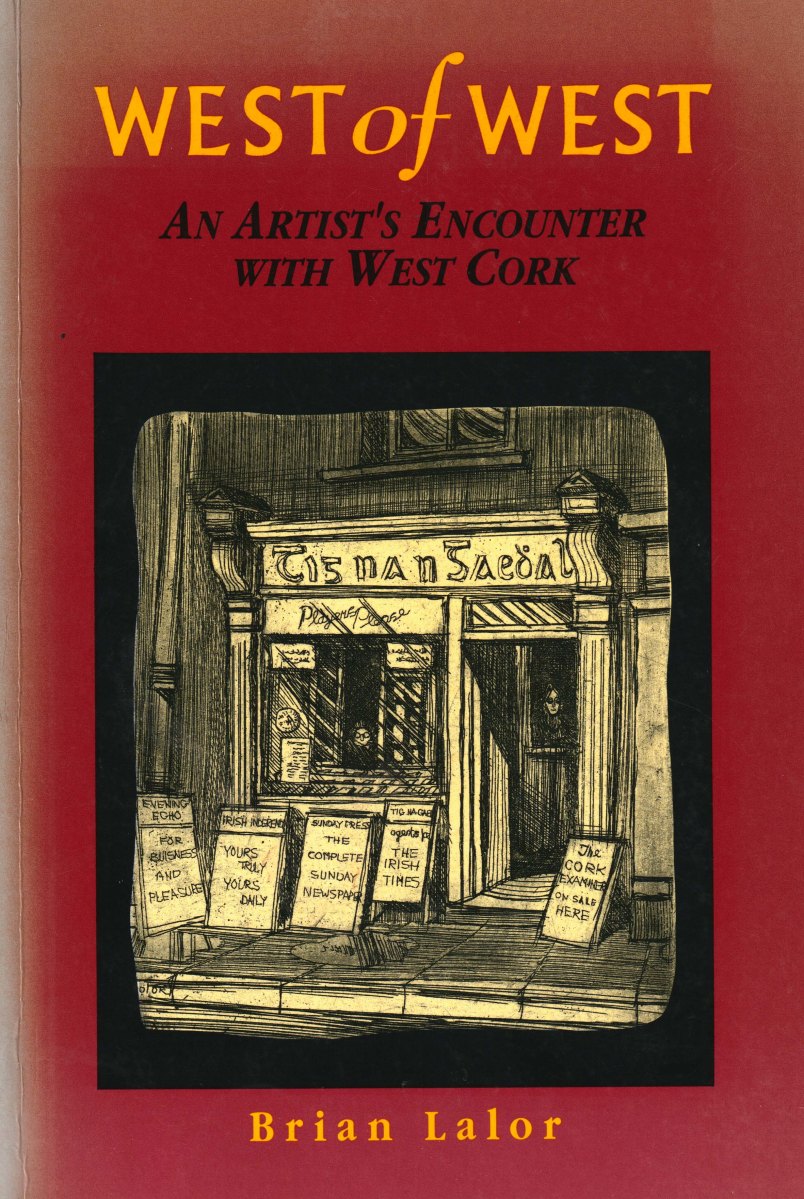

Perhaps this book review is a little late arriving? The book was – after all – published by Brandon of Dingle in 1990: thirty two years ago! The artist, and I, were in our forties then. But – don’t hesitate – although it’s out of print you can find copies readily available on many booksellers’ websites. You can spend a Euro (the postage will cost four times that!) or many Euros: but it’s well worth whatever you have to pay.

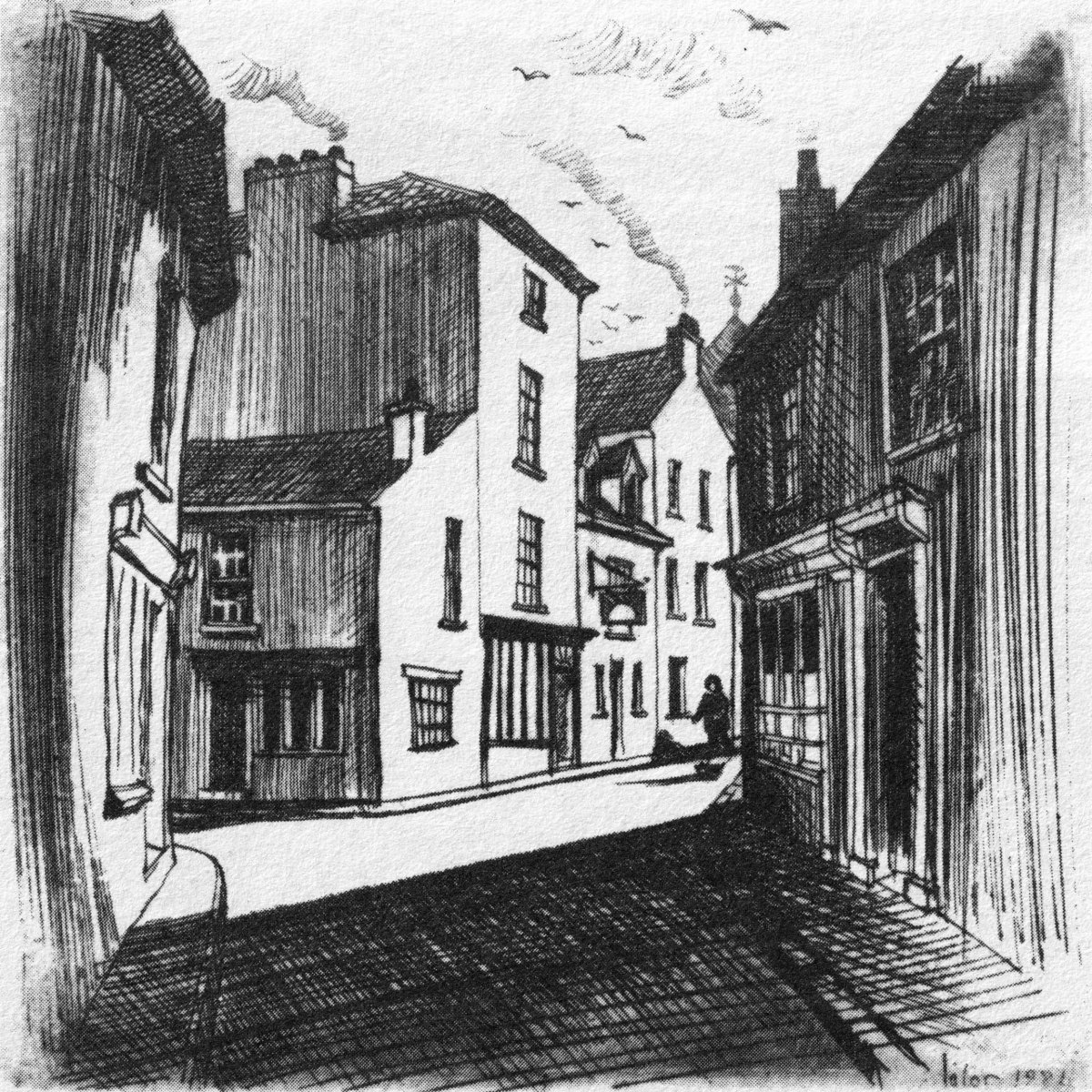

Here it is: a modestly sized paperback volume. But it punches well above its weight. It is beautifully written, and exquisitely illustrated. For everyone who is interested in West Cork, Ireland or the art of engraving it’s a must for your bookshelves. And, historically, it’s fascinating: the cover picture, above, shows Tig na nGaedheal (locally known as Brendan’s) – once described as ‘the greatest and most famous sweet shop ever in Skibbereen’. Sadly, Martha Houlihan, who ran it with her husband Brendan, passed away a little while ago and the shop is no longer trading. It’s still a significant feature in the town streetscape (below). Note the figures looking out of the door and window in Brian’s etching – a typical humorous touch.

The book includes nigh on a hundred of Brian’s engravings. This is only a fraction of the huge body of work he has created in his lifetime to date, and he’s never idle. It’s good to know that Uillinn – the West Cork Arts Centre gallery – has a retrospective of Brian’s work in the pipeline. It will be impossible to show more than a fraction of the art he has produced so far, but we certainly look forward to experiencing that selection.

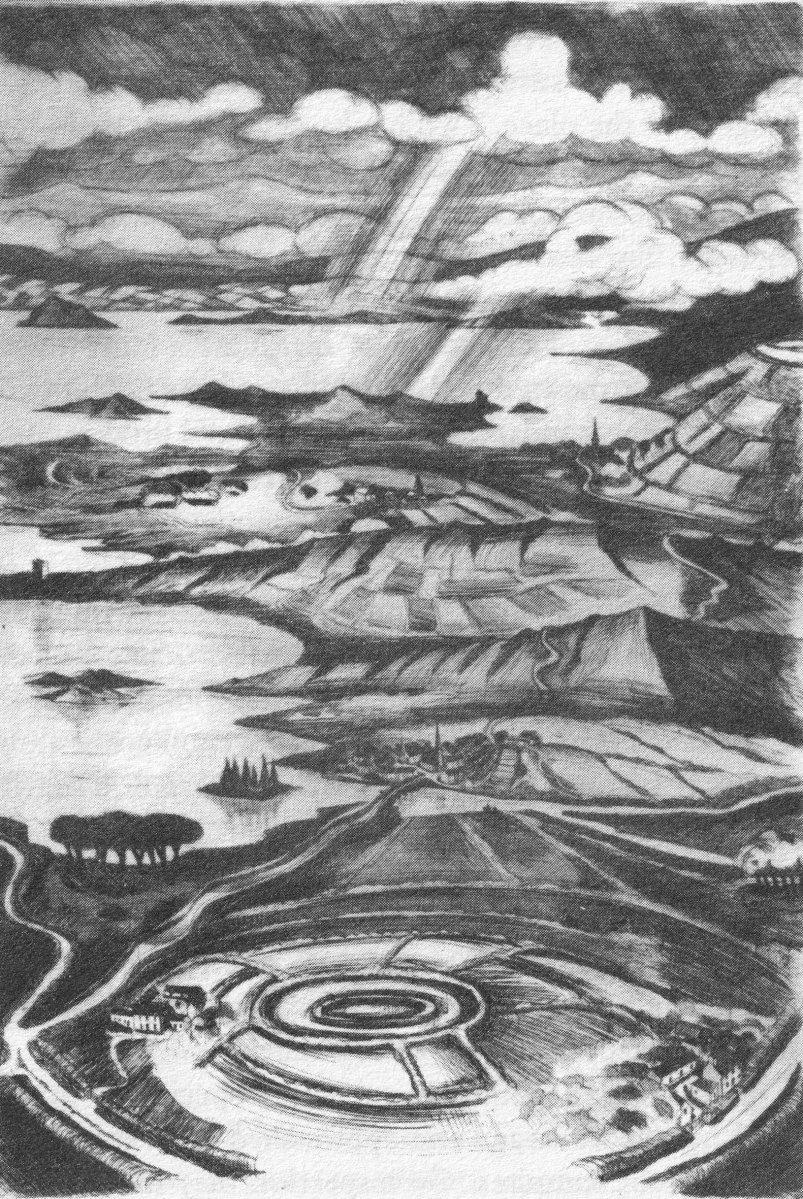

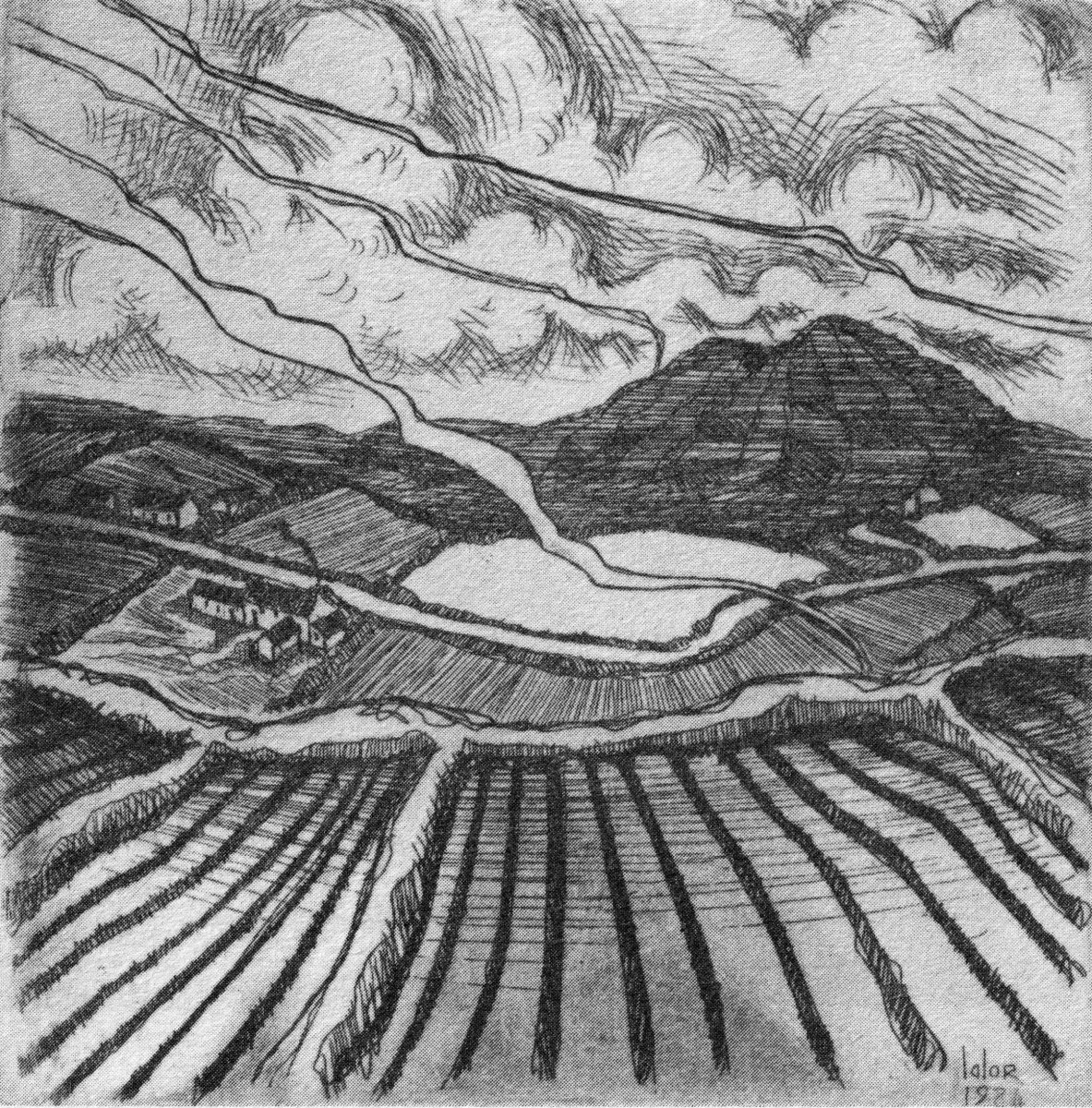

What I personally enjoy about Brian’s works in this book is the atmospherics that they create. Take, for example, The Dark Edge of Europe, above. The breadth of its content is overwhelming: it’s the landscape of West Cork summed up in gradations of grey, with coastline, lanes, settlements, hills and distant mountains, focussed on a foreground which features an ancient hill-fort. A tale of occupation and morphology: an eternal human story. The illustrations in the book are accompanied and amplified by wonderfully crafted written descriptions.

. . . Defining the high spots in the ribs of land, and distributed with apparent regularity all over this landscape, were lush green rings. Single, and occasionally double or triple concentric rings of grassy banks, these features resembled a giant’s game of quoits, forgotten and left to decorate the landscape. The gargantuan quoits are of course the ring forts or fairy rings of the Irish countryside, and outlined the forms taken by the rural farmsteads and dwellings from pre-Christian times down to the sixteenth century. Each ring represented an earthen rampart on high ground, with perhaps a dry moat or further rampart encircling some wattle huts. Simple and utilitarian, this form of dwelling satisfied the political and practical exigencies of the day – or aeon, for that matter. Rural life was lived in the midst of the land, without congregating in towns or villages . . .

The Land of Heart’s Desire: West of West, Brian lalor

Mount Gabriel dominates much of the landscape in our part of West Cork. Brian’s view, above, is titled Mount Gabriel Gorse Fires. The artist ‘discovered’ remote West Cork back in the 1970s. In the book he describes the journey:

. . . The road wound away into the distance, a ribbon of reflected light, and the weaving shapes of the blackthorns threw a black Gothic tracery across the landscape. The immediate surrounding had a silvery sharpness, the precision of a lunar landscape; brightly outlined walls enclosed pools of darkness. We were no longer at the door to West Cork but in its very interior. We had arrived . . .

Well Met By Moonlight: West of West, Brian Lalor

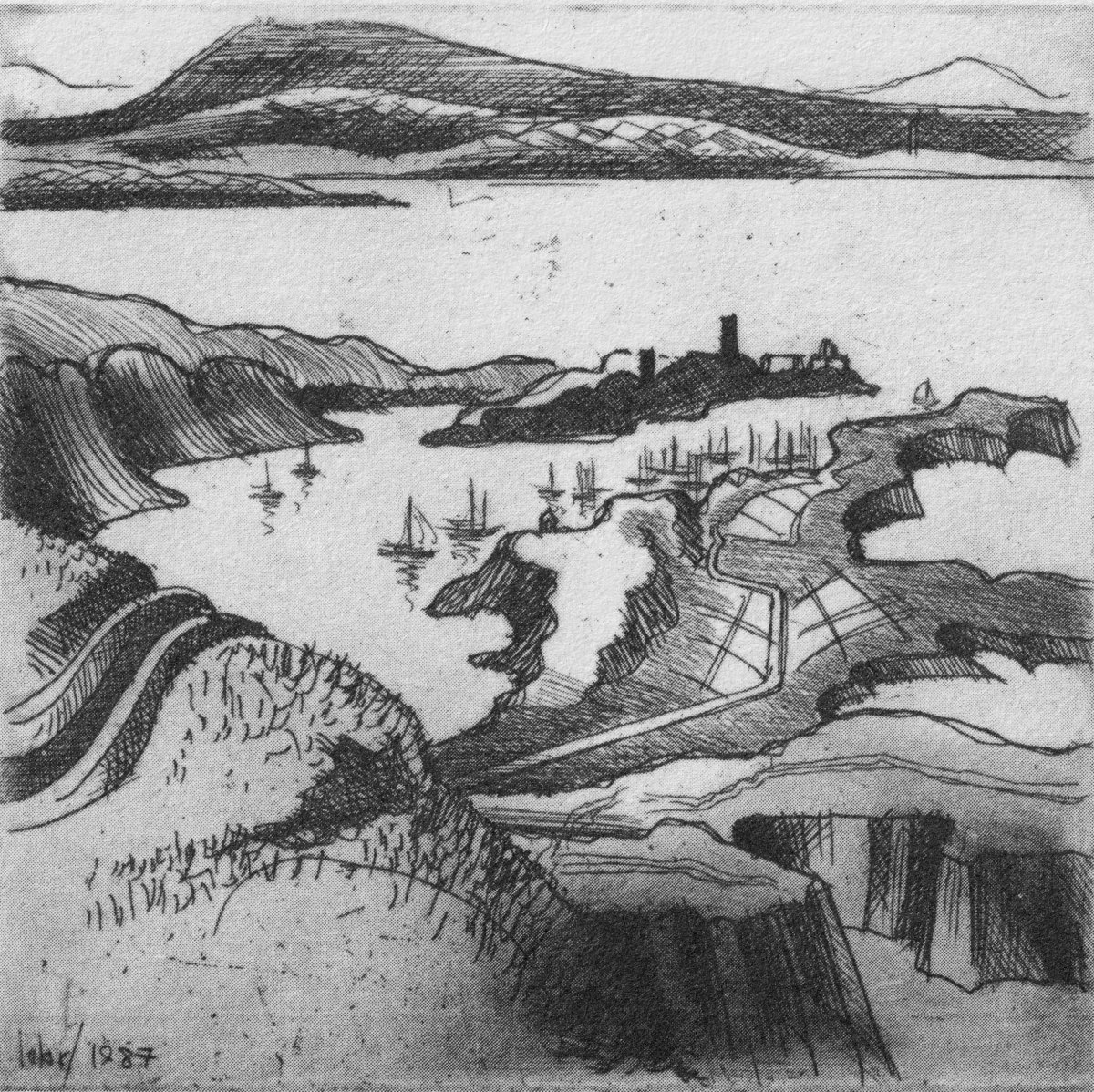

Essential to the intimate knowledge of West Cork’s landscape is the sea – and the coastline which encompasses it. This view is titled Rock Island & Crookhaven. Brian enhances the rendering with a description:

. . . From the heights of Brow Head the outline of Rock Island at the mouth of the harbour resembles a partially submerged submarine, its twin customs-observation buildings the conning towers of this strange naval mammoth. An ill-assorted collection of buildings adhere like barnacles to the back of this submarine: the roofless lighthouse barracks, a defunct fish factory and an abandoned, rambling Victorian mansion suggest an unfavourable location. Wedged in the little cove in front of the mansion is the hulk of an old wooden trawler. A graveyard of vanished days and forgotten hopes . . .

Coastline: West of West, Brian Lalor

Ballydehob’s 12-arch bridge – or railway viaduct – must be one of the most profusely illustrated and photographed features of West Cork. The Schull, Ballydehob and Skibbereen tramway was a significant piece of transport infrastructure that ran from 1886 until 1947. It’s a fascinating piece of Victorian engineering, the first 3ft gauge railway line to be built in Ireland. Everything about it was eccentric: here’s one of my RWJ posts setting out the history of the line. Brian has a little anecdote well worth the recounting:

. . . As it is one of the most pleasing architectural features of the local landscape, I drew the Twelve Arch Bridge on many occasions and it reappears in a variety of forms amongst these etchings. One village magnate commissioned me to do a large picture of this monument for his new house. The price was agreed and the picture eventually produced. I had chosen an angle which showed the bridge emerging as it does from thickets of brambles and conifers on either side of the water. Delicate fronds of foliage wound in the foreground of the picture and the subject itself basked in the distance, looking solid and ancient. I was quite pleased with the results. When I presented it to my patron he gazed at it in silence for a long time. Then with a large and calloused hand he ran his index finger across the view a number of times, shaking his head slowly as he did so. ‘No. no good at all, It won’t do,’ he muttered more to himself than me. He had been counting the arches. In my enthusiasm for the atmosphere of the piece the accurately rendered number of the arches had become obscured, those on the extreme edges becoming partially lost in the undergrowth. The commission was rejected. If you are paying for twelve arches you don’t want to be short-changed with ten and two halves!

Coastline: West of West, Brian Lalor

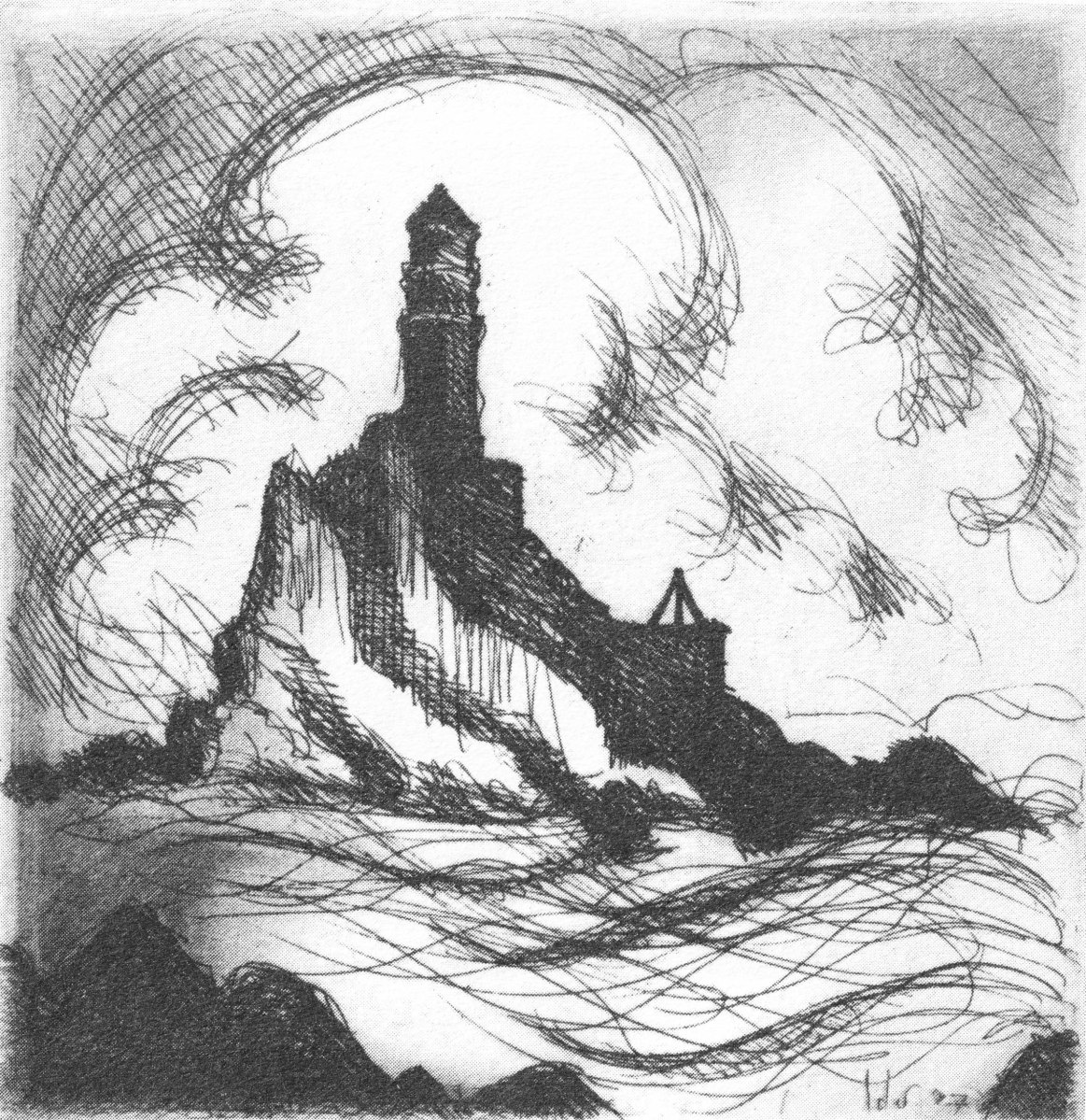

Fastnet. An iconic silhouette – perhaps a fish-eye view? The lighthouse is a ubiquitous element of structure which can be seen from all the waters and islands of Roaring Water Bay. Brian’s words:

. . . Roaring Water Bay encompasses an area of about a hundred square miles of water between Baltimore in the east and Crookhaven in the west. The tortuous coastline of the bay, as of much of the rest of West Cork, is punctuated by small coves, each with an old stone pier or miniature harbour. Up to the mid-nineteenth century these were the arteries of communication and trade and a wide array of lighters, barges, rowboats and yawls plied the coast, ferrying freight around the rim of the land rather than through it. Never far from the safety of land, they darted from port to port with the assurance of safe harbours at frequent intervals to reduce the threat from treacherous seas. Today, however, only the yachtsman holds this perspective on the land; it is a medieval cartographer’s view of the world: good on outlines, vague concerning the interior . . .

Coastline: West of West, Brian Lalor

The eye of the artist searches out ways to tell a story or unfold a scene in graphic simplicity. This is St Brendan Crookhaven: a simple church that is dear to the hearts of mariners, and has long been so.

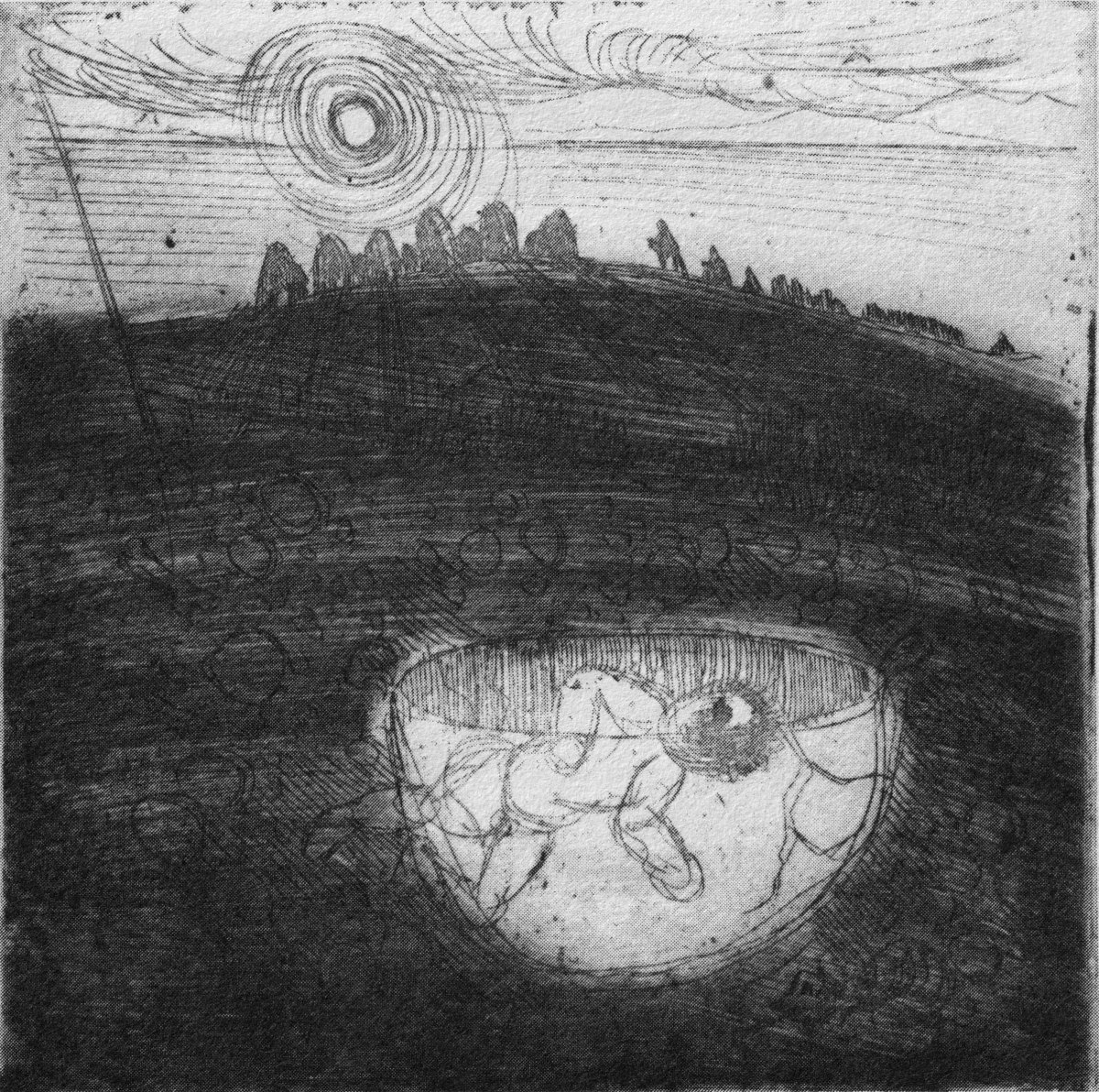

Stone Circle and Child Sacrifice is a thought-provoking piece. These ancient sites date back thousands of years: there are many here, beyond the West. We wonder at them, and can only guess at the significance they had to their constructors.

. . . The Landscape of the mind, which co-exists, interlocks and overlaps with the geographer’s vision, is an intangible, ephemeral thing. You may encounter it unexpectedly on a moonlit night or on some deserted headland, or perhaps in the dim light of a public bar. In this part of the world, soaked in memories and half-memories of the past, much is implied rather than stated. Like the collective unconscious, the landscape, too, is composed of a multitude of intertwining details. This collection of etchings of West Cork is concerned with those details: with small corners of towns and villages, with oddly-shaped fields and erratic skylines. Each etching is a vignette of landscape, architecture or environment. The pictures are organized around a number of themes yet the material as a whole has such an overall unity that what illustrates one section also has relevance for another. The point which they make is a collective one . . .

WELL MET BY MOONLIGHT: WEST OF WEST, BRIAN LALOR

Brian’s book is as much about the human side of West Cork as it is about the natural or supernatural. He illustrates towns – Kinsale, above – and the landscape. For me, this is a very significant little volume: the travels described within it echo my own journeying through this most special of places. Thank you, Brian, for so vividly enhancing my appreciation of West Cork.

Kilcoe

It’s December 3rd (yesterday) – St Barrahane’s feast day, that is. He’s one of our local saints and not a lot is known about him. There are other St Barrahanes – or St Bearchán as it’s more commonly spelled – a whole raft of them, in fact from around the country. But this one belongs to Castlehaven.

Now, I am not normally given to honouring saints’ feast days, but there are exceptions. St Patrick’s, after all, is a national holiday, and St Brigid’s soon will be, so it would be rude not to. St John’s Eve is big in Cork and this year I did the rounds in my local graveyard – see this post for my lovely experience. That’s Castlehaven graveyard, below, right on the sea – the sea that Amanda and I are bobbing around in, in the lead photograph.

You remember Conor Buckley and his adventure and outdoors company, Gormú? To jog your memory, take a look at Castlehaven and Myross Placenames Project and Accessible August. He’s an all-round dynamo, whose idea of fun is to take people swimming at dawn in the middle of winter. But on this occasion, there was heritage to back him up – a local custom of going to St Barrahane’s well to get water on Dec 3rd, as a cure, but also as a talisman against any kind of accident at sea. Important, in this maritime location.

We gathered at the top of the road at dawn and walked down to the sea. Conor invited us to go barefoot as the original pilgrims would have done, and there were actually a few takers.

Then up to the holy well – about 20 of us. Conor told us about the traditions associated with this particular well, and asked Amanda to speak about wells in general. Declaring that she “has done more for holy wells than anyone else in Ireland” he then invited her to be first to the well – being first was also particularly auspicious in the local folklore.

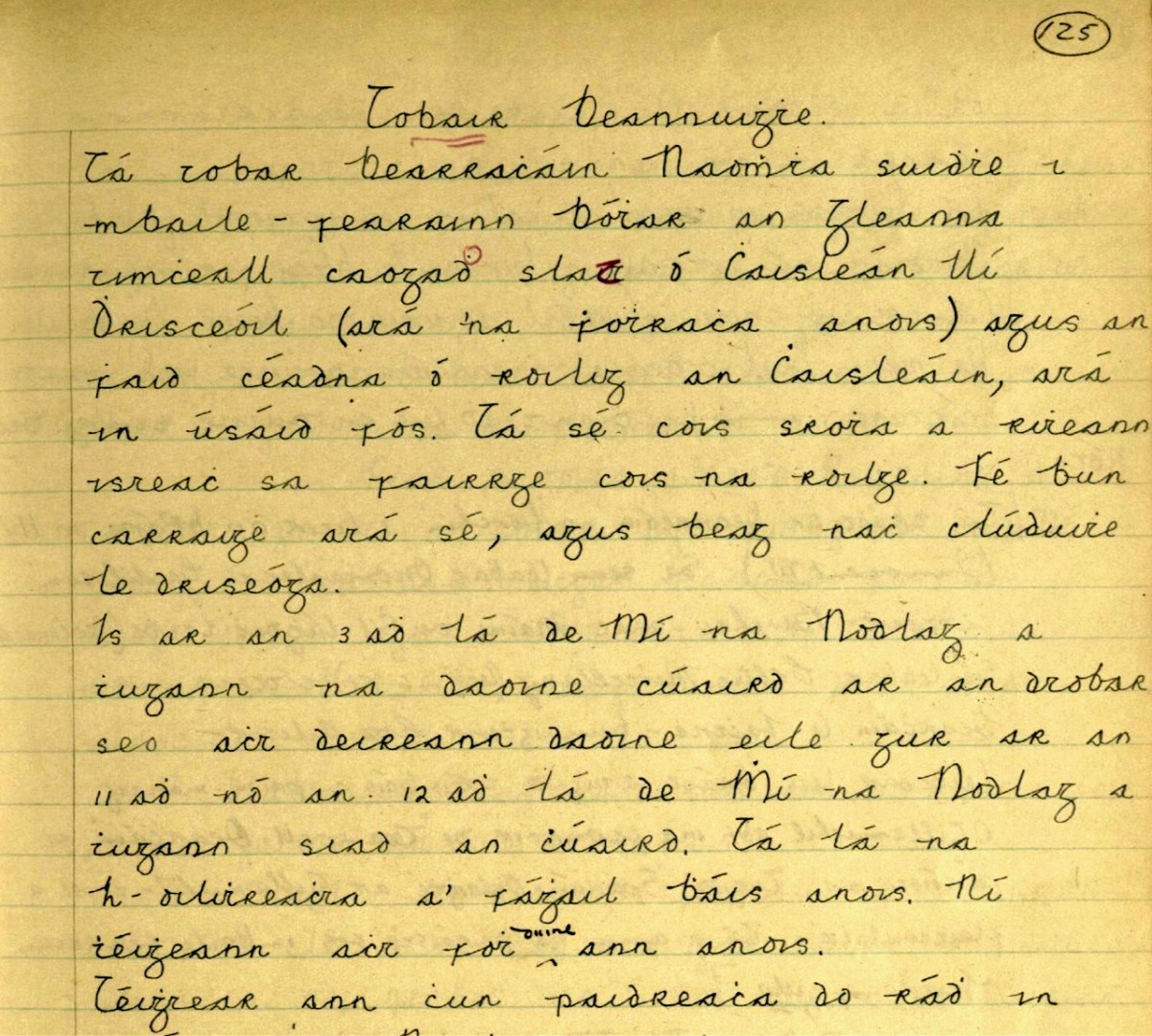

The well contains a sacred eel (to see it brought good luck forever) and a cure for fevers that lasted all year. People would visit at any time, but particularly on Dec 3rd to collect water and take a bottle home with them. By the 1930s, when this account (below, in Irish) from Dooneen School was given in the Dúchas Schools Collection, only a few people were still coming. The onus on the pilgrim was relatively light – just a few Hail Mary’s and the Sign of the Cross and then you could drink the water. Some people left rags or a coin.

After the student’s writing is a Nóta, written by the headmaster, R Ó’Motharua.

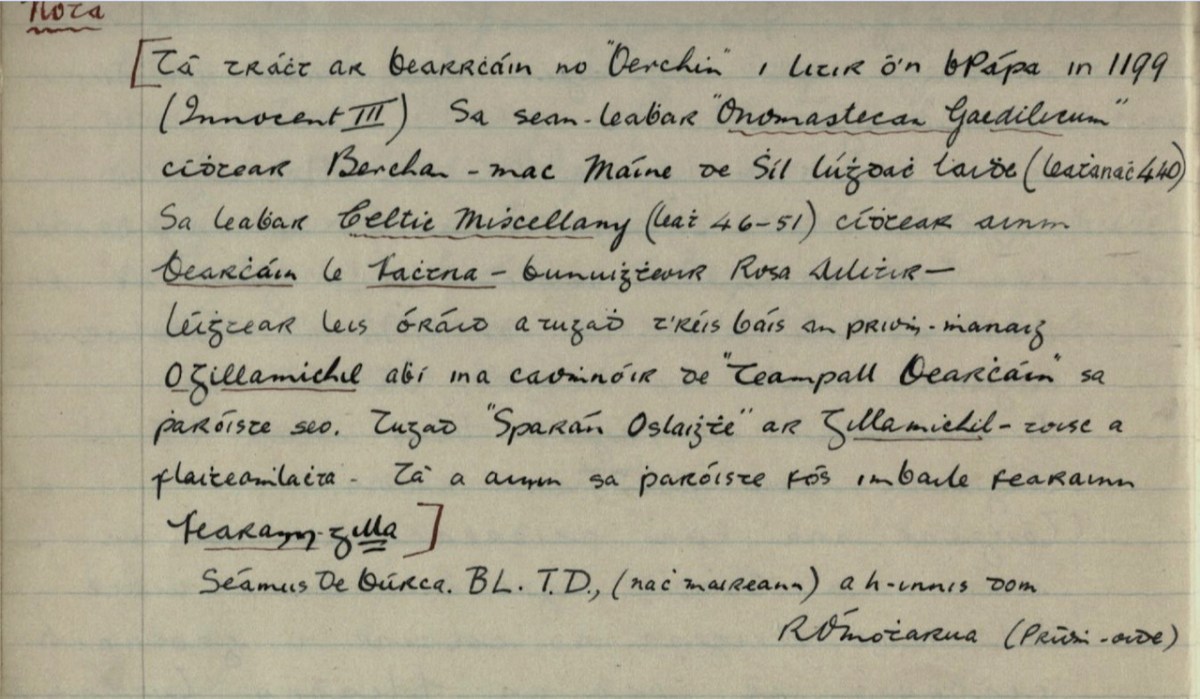

The information for the Nóta came from James Burke, a noted local historian, TD (member of the Dail, or Irish Pariament) and Editor of the Southern Star.* He took a scholarly interest in local saints, of whom Barrahane was a prime example. Here is my translation (corrections welcome).

There is mention of Bearrcháin or “Berchin” in a Papal letter in 1199 (Innocent III). In the manuscript “Onomastecan Gaedilicum” one sees Berchan – son of Máine of the Race of Lúghdach Maidhe (Page 440). In the book Celtic Miscellany (page 46-51) one sees the name of Bearcháin with Fachtna – the founder of Rosscarbery – he was reading with him an oration that was given after the death of the Abbot O’Gillamichil who was the patron of Teampall Bearcháin [St Bearcháin’s Church] in this parish. They called Gillamichil “Open Purse” – because of his generosity. His name is still in the parish in the townland of Farranagilla [meaning Gilla’s Land].

https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4798763/4796172

Farranagilla, by the way, is a townland halfway between Castletownshend and Skibbereen. This accords with other information I have from James Burke about St Barrahane. In a letter to Edith Somerville of February 1917 he says:

When we come to Saint Barrahane (Irish Bearćán) we are in more shadowy ground.

There was a great St Bearchan a noted prophet of Cluain Sosta in Hy Failghe of whom there is much (exhaustive) knowledge but I have elsewhere tried to prove that the patron of Castlehaven parish was a native of West Cork and is identified with the Bearchan mentioned in the genealogy of Corca Laidhe but he is only a name. He certainly was the patron of Castlehaven which as early as 1199 and no doubt much earlier was called Glenbarrahane.

From a letter in the Somerville archives, Drishane House. Quoted with permission**

James Burke had originally set out this information in his paper for the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society of 1905 on Castlehaven and its Neighbourhood, pointing out that the original name for Castlehaven Parish was Glenbarrahane, after its patron saint. In his magisterial work, A Dictionary of Irish Saints (Four Courts Press, 2011, p96), Pádraig O’Ríain agrees with the notion that the saint belonged to the Corca Laighde family, despite some misgivings. He also adds local tradition maintains that Bearchán came from Spain.

Why was James Burke writing about St Barrahane to Edith Somerville? She was researching appropriate saints for the window she and her family had commissioned from Harry Clarke (of which more in a future post). A lack of information didn’t stop Harry Clarke from imagining what Bearchán might have looked like. In his Nativity window in St Barrahane’s Church of Ireland, he gives full reign to his imaginative vision and depicts him as a monk.

He gets the full Harry treatment – large eyes, a face full of wisdom and compassion, long tapered fingers. He is writing on an extended scroll – and the scroll hides a surprise, only visible in close-up and upside down.

The well itself is a little beauty – half hidden in the undergrowth and accessed by a wooden bridge. It is festooned with fishing floats – fisherman left them here to protect them at sea – rags, and rosaries. The water is fresh and clear.

In fact, the water from this well is used to baptise infants in both the Catholic and Protestant churches of Castlehaven Parish!

So there you have it – what we know about St Barrahane and the traditions that surround him. We collected a jug of the water from the well for anyone who wanted to fill a bottle. As Joey in Friends used to say – Could I be wearing any more clothes?

But, this being Gormú, there was more to the day – the visit to the Holy Well was to be followed by a swim! Yikes! Amanda and I egged each other on during the week (I will if you will)) and finally decided it had to be done. And guess what – it wasn’t that bad! In fact, the water felt if anything slightly warmer than the surrounding air. In case anyone thinks I am virtue-signalling here (Look at me, swimming in December!) we didn’t stay in long, and there was a lot of shrieking involved. Some of the real swimmers emerged half an hour later.

There was an immense sense of camaraderie as we chowed down on our hot porridge and tea afterwards. Vincent O’Neill presented Amanda and me with the latest issue of the Castlehaven & Myross History Society Journal.

It is a great thing that Conor and other local historians have taken on the task of re-activating this pilgrimage and it felt wonderful to be a part of it.

Nurturing small native plant/pollinator/wildlife habitat in western Oregon

Travels on foot

Another bicycle adventure in France

In which M & A cycle to — and over — the Pyrenees and into Spain

the town that time forgot

Outside of the Academy

J&M invade the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Encounters with women in Irish theatre history

Our garden, gardens visited, occasional thoughts and book reviews

History of People and Places

This is not an Oxymoron

It's all about the photos.....

Archaeology -- Pseudoarchaeology -- School -- The good, bad, and the ugly about life in the trenches and life as a student

Welcome to the UCD Library Cultural Heritage Collections blog. Discover and explore the historical treasures housed within our Archives, Special Collections, National Folklore Collection and Digital Library

History of People and Places

Virtual Music Making

Take a Chair: talking theatre and creativity