There are parts of West Cork that seem to hold within them all the memories and markers of eons. Such a place is Arduslough, on the high ground across from Crookhaven (below, map and photo) and west of Rock Island (above).

Technically, the places we explored are in three different townlands – Tooreen, Arduslough and Leenane, but mostly they fall within the boundaries of Arduslough. The name has been variously translated – Árd means high place and Lough means lake, both of which seem appropriate, but in fact the placename authority, Logainm, renders it as Árd na Saileach meaning High Place of the Sallies, or Willow Trees. Not much in the way of willows is obvious now, but the lake is certainly central to your view in the townland.

The Lake is the source of drinking water for Crookhaven and is the home, according to a story collected in the late 1930’s, of. . .

. . . an imprisoned demon of the pagan times. He is permitted to come to the surface every seven years on May morning and addresses St. Patrick, who is supposed to have banished him, in the following words “It is a long Monday, Patrick”. The demon does not speak in the English but in the vernacular. The long Monday refers to the day of General Judgement. Having expressed these words his chain is again tightened, and perforce he sinks to the bottom of the lake for another period of seven year His imprisonment will not expire till the last day.

We saw no sign of the demon and the lake looked remarkably untroubled, with its floating islands of water-lilies.

For a relatively small area, Arduslough abounds in archaeological monuments – there are four wedge tombs, three cupmarked stones, a standing stone and a piece described as either an Ogham Stone or Rock Scribings, depending on what you read. The remains of old cabins dot the landscape too, reminding us that this was a much more populous place before famine and emigration decimated the population.

The standing stone, and Robert with Jim and Ciarán O’Meara

Arduslough is the home of esteemed local historian Jim O’Meara, who grew up in Goleen but spent most of his adult life teaching in Belfast. We met up with Jim and his son Ciarán, who very kindly offered to show us the Ogham stone. It was so well hidden under layers of brambles and bracken, and built into a field fence, we would never have found it on our own.

It is impossible to say if it is real, or even false Ogham, as it is heavily weathered and lichened, but if we turn again to the School’s Folklore Collection, we find this entertaining account of it:

There is a stone in Arduslough, a townland on the hill to the north of Crookhaven, on which are very old characters or ancient writing. It is very difficult to discern these markings now as the centuries during which they were exposed to the weather have obliterated them. The following story explains the origin of them.

In ancient times there lived in Toureen a man named Pilib. He informed on some party of Irish soldiers who were hiding in the heather there. The enemy came on them and burned the heather round them in which the soldiers perished. The stone was erected in this spot and the event was recorded on the stone. Years passed and the language underwent a change. In later years the people did not understand what was recorded on the stone, and went to the Parish priest asking him to interpret it. He translated it as follows – ‘that every sin will be forgiven but the sin of the informer Pilib an Fhraoich [Philip of the Heather].

We had previously located one of the three cup-marked stones, including a visit a couple of days earlier with Aoibheann Lambe of Rock Art Kerry (below). Ciarán thought he might be able to find another one, but extensive searching and bracken-bashing failed to turn it up.

The folklore collection is full of references to mass rocks, druid’s altars, and giant’s graves, as you would expect from the number of Bronze Age wedge tombs recorded in this area. (For more on Wedge Tombs, see my post Wedge Tombs: Last of the Megaliths.) Two of them are situated on the slope above the lake (below) and we left them for another day. A third is hard to spot and indeed we didn’t.

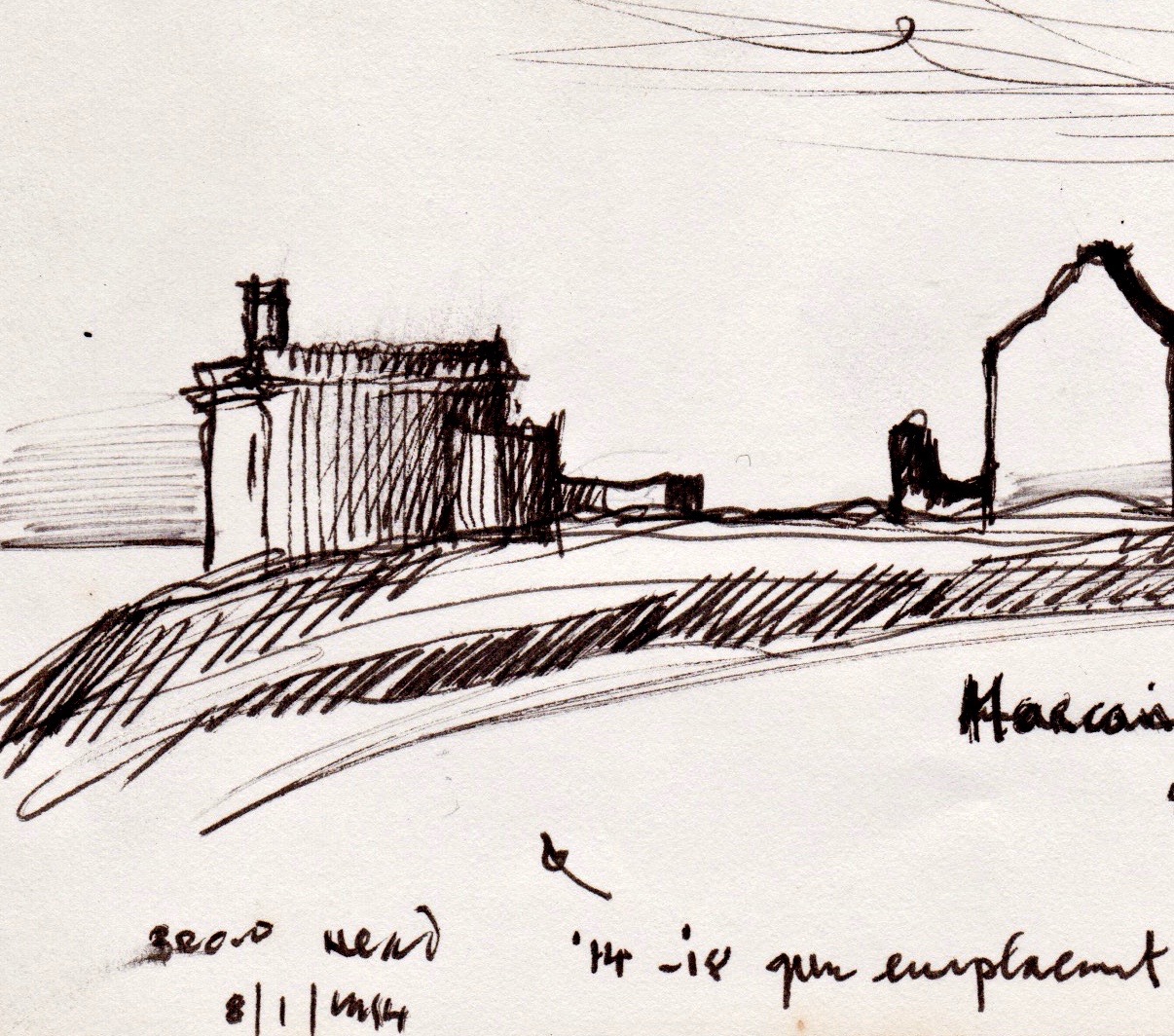

We headed up to the high ground west of the lake to find the one that local people still call the Giant’s Grave. What a spectacular setting this is! First of all, you are now on a plateau with panoramic views in all directions. West lie the two peninsulas of Brow Head and Mizen Head and the boundless sea beyond.

This is heathland, covered in heather and Western Gorse – a colour combination that has the power to stop you in your tracks – and traversed by old stone walls.

From this colourful bed the stones of the Giant’s Grave arose, pillars silhouetted against the sky. It’s actually in the townland of Leenane, just outside the boundary of Arduslough. When Ruaidhrí de Valera and Seán Ó’Núalláin conducted their Megalithic Survey in the 1970s they commented that the tomb was ‘fairly well preserved’ and ‘commands a broad outlook to the south and east across the sea to Cape Clear and Roaringwater Bay.’ They interpreted what was there as a wedge tomb, although with some uncommon features.

First of all, they said the tomb was ‘incorporated’ within an oval mound. While mounds are known for wedge tombs, they are unusual and most of the Cork examples, included excavated ones, show no trace of a mound. Stones sticking up here and there, protruding from the mound, they interpreted as cairn stones.

Secondly they noted two tall stones on the north side of the tomb – one is still standing and clearly visible (above and below) – whose function was ‘uncertain.’

Two tall stones at the south west end (above) seemed like an ‘entrance feature.’ Our own readings at the site indicated that the orientation was to the setting sun at the winter solstice, a highly significant direction to where the sun sets into the sea.

So – an unusual wedge tomb. Elsewhere in their report de Valera and Ó’Núalláin state repeatedly that a hilltop setting and a rounded mound are consistent with passage graves. However, at the time no passage grave had been identified this far south and they were thought to have a more northerly distribution. Since then, two have been identified in County Cork – one at the highest point on Cape Clear, which is visible from this site, and one in an inter-tidal zone between Ringarogy Island and the mainland. Perhaps it is worth considering whether, rather than a wedge tomb, this site may be a passage grave, like the one that Robert writes about this week in Off the M8 – Knockroe Passage Tomb or ‘Giant’s Grave’.

Whatever we label it, this Giant’s Grave is a spectacular site. It’s not hard to imagine, up there, that Neolithic and Bronze Age farmers were just as awe-stricken as we were with the magnificence of the surroundings. Tending their herds, they marked the seasons with the great movements of the sun and moon, and commemorated their dead with enduring stone monuments. More recently, people invested the landscape with myth and stories. Walking the hilltops, you know you are in the footsteps of all who went before.