Two young musicians – from the collection of Tomás Ó Muircheartaigh, who documented life in rural Ireland between the 1930s and the 1950s. We do not know at what outdoor gathering this atmospheric picture was taken, but perhaps there is a polka or a slide being played there…

Way back in the last century (it was the nineteen seventies actually) I first came to Ireland in pursuit of traditional music. I found it a-plenty. At that time, the music of the Sliabh Luachra was very much in vogue: local sessions and Fleadh Ceols were full of polkas and slides…

Classic recordings of traditional music collected from the Sliabh Luachra during the sixties and seventies: The Star above the Garter is published by Claddagh, while the others are from the Topic Record catalogue

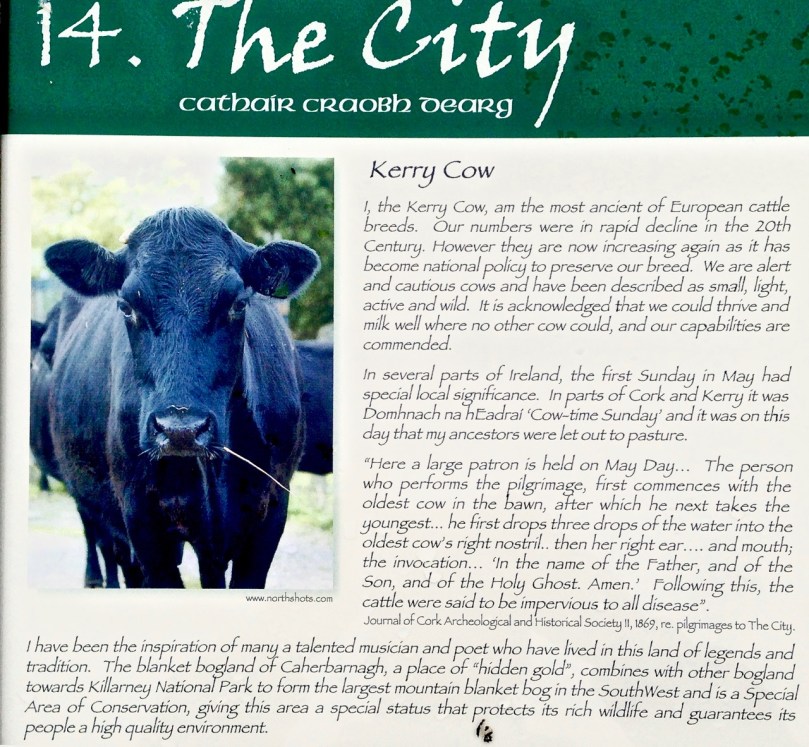

My post last week came to you from the City of Shrone, which is within this area, in the border country of Cork, Kerry and Limerick. The strong surviving music traditions here have an unmistakeable character – fast and lively. I was reminded of that tradition this week when I came to the wonderful Fiddle Fair in Baltimore and listened to Tony O’Connell from the Sliabh Luachra in recital with Brid Harper, a highly regarded Donegal fiddler. They are an excellent duo – here’s a little taster from that concert (Kerry Slides):

As an aspiring concertina player myself I was bowled over by Tony’s playing, especially of the quintessential Kerry slides. But what is a slide you might ask? And how do you tell a slide from a jig?

Saturday’s recital in Saint Matthew’s Church, Baltimore: Brid Harper and Tony O’Connell playing Kerry Slides

Here’s some help, extracted from discussion boards, specifically on the subject of slides and jigs:

…Uninitiated listeners and even some tune-book editors have mistaken slides as hornpipes, single jigs, polkas, or double jigs, since slides share various traits with each. Once you know a few, you realise they are distinct from any of those…

…Note that slides are peculiar to the Southwest of Ireland, and some are directly related to double jigs, single jigs, or hornpipes played elsewhere in Ireland. Musicians quite familiar with slides are generally unfamiliar with single jigs, and some otherwise respectable authorities on the slide have rashly pronounced that single jigs “are the same as slides.” We can have some sympathy with that by understanding that these musicians simply use the term “single jig” to mean “slide,” and are apparently unaware of the existence of the distinctive “single jig” rhythm in Irish music. Over the course of the 20th century the customary notation for slides shifted from 6/8 to 12/8, which I think is an improvement in accuracy…

Both these statements (from irishtune.info) tell us about the confusion between jigs and slides, but they don’t tell us exactly how you define either of them. Let’s try this, from the same source, regarding slides:

…The tempo is rather quick, often in the 150 bpm range, if you were to count each heavy-light pair as a beat. But in practice each beat of a slide (counting around 75 bpm now) gets two pulses, which is either a heavy-light pair (very close to an accurate “quarter note, eighth note” distribution) or a quite even triplet – not a jig pattern. Thus if all four group-halves in a bar were triplets – which is uncommon – you’d have a twelve-note bar. The ratio of heavy-light pairs to triplets in a slide is slightly in favour of the pairs, which again clearly distinguishes them from double jigs. Most slides break the pattern once or twice in a tune by delaying the strong note for a bar’s second group until that group’s second half, creating a cross-rhythm with respect to the foot taps. Other unique characteristics of slides are not necessary additional information for identifying them – only for playing them…!

I’ve puzzled over this (and other advice) for some time: I sort of understand it, but I think it’s impossible to describe a rhythm in words… However, I was pleased to find this mnemonic for slides by the poet Ciaran Carson – it says it all:

“blah dithery dump a doodle scattery idle fortunoodle”

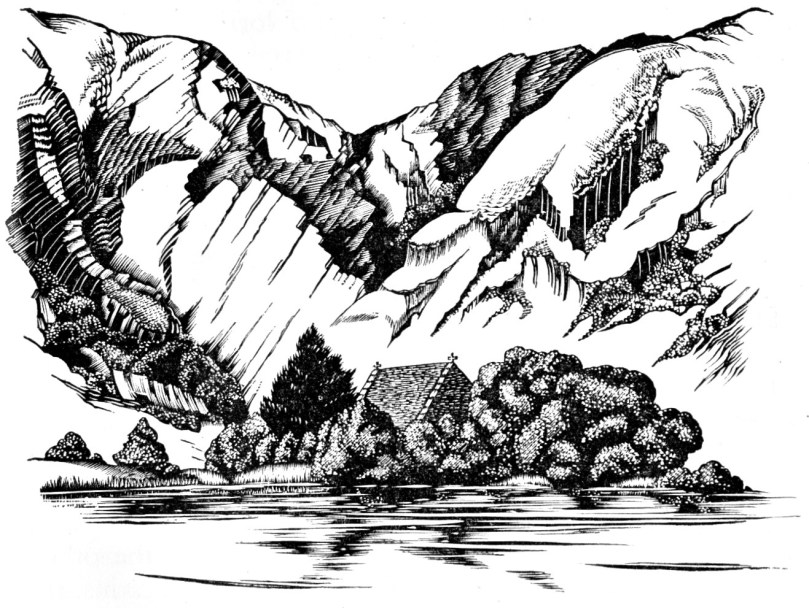

An evocative engraving of Gougane Barra, in the Sliabh Luachra, by artist and writer Robert Gibbings, taken from Lovely is the Lee, J M Dent, 1945

How about polkas and reels? Polkas, in particular, are popular in the Sliabh Luachra tradition:

…The polka is one of the most popular traditional folk dances in Ireland, particularly in Sliabh Luachra. Many of the figures of Irish set dances are danced to polkas. Introduced to Ireland in the late 19th century, there are today hundreds of Irish polka tunes, which are most frequently played on the fiddle or button accordion. The Irish polka is dance music form in 2/4, typically 32 bars in length and subdivided into four parts, each 8 bars in length and played AABB. Irish polkas are typically played fast, at over 130 bpm, usually with an off-beat accent… (Also from irishtune.info)

Reels are probably the most popular tune type within the Irish traditional dance music tradition:

…Reel music is notated in simple meter, either as 2/2 or 4/4. All reels have the same structure, consisting largely of quaver (eighth note) movement with an accent on the first and third beats of the bar…

At the Baltimore Fiddle Fair, informal sessions are essential interludes

Definitions are all very well and these can only be generalisations. In the end it’s what is being played – and what you hear – that counts. For me, the music in Ireland is like history: it’s built into the landscape and the psyche. Irish people are survivors and have travelled all over the world and back. So has the music! This was emphasised today when we had another excellent recital in the church by Dylan Foley and Dan Gurney, fiddle and accordion.

They both come from the Southern Catskill Mountains in New York State. Much of the Irish music they play was learnt directly from Father Charlie Coen who emigrated to the United States from the village of Woodford in County Galway in 1955, bringing the music traditions from East Galway with him. Here’s an excellent example of the music travelling across the world and back again: Fr Coen played The Moving Cloud reel on his concertina, but his instrument had some buttons missing so he adapted it, and the adapted tune is what we heard Foley and Gurney playing in the church today. Listen first to another Fiddle Fair maestro, Noel Hill playing the reel from his 1988 album The Irish Concertina:

Now the same reel which has travelled from Ireland to Baltimore via the Catskill Mountains:

I hope you can hear those ‘odd’ notes! But there’s nothing so right or so wrong in Irish music: the grand finale for us today was a memorable concert with French Canadian fiddler Pierre Schryer, Donegal box player Dermot Byrne and Australian born guitarist Steve Cooney. They played music with an Irish bias but harvested from many traditions. It left us breathless…