County Cork is well-endowed with the sites of Napoleonic-era signal towers. By my calculations there are 20 sites in this county, almost a quarter of the generally accepted number of sites around the whole island. For a map of the 81 locations identified by Bill Clements in 2013 have a look at part 2 of this series – Ballyroon Mountain. Today’s subject is Downeen Signal Tower, close to picturesque Mill Cove, a naturally sheltered quay around which a small settlement can be found, most active in the summer months.

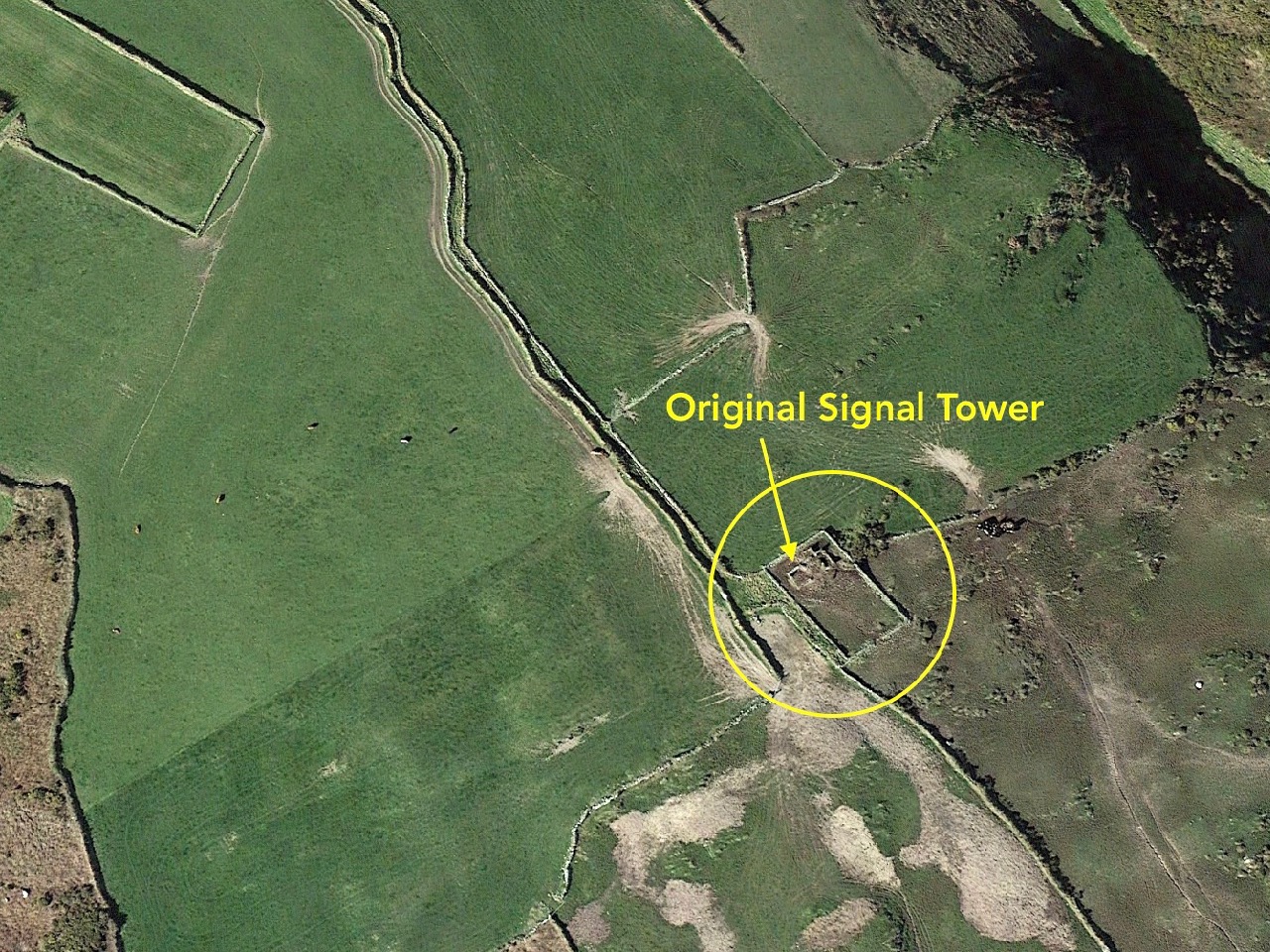

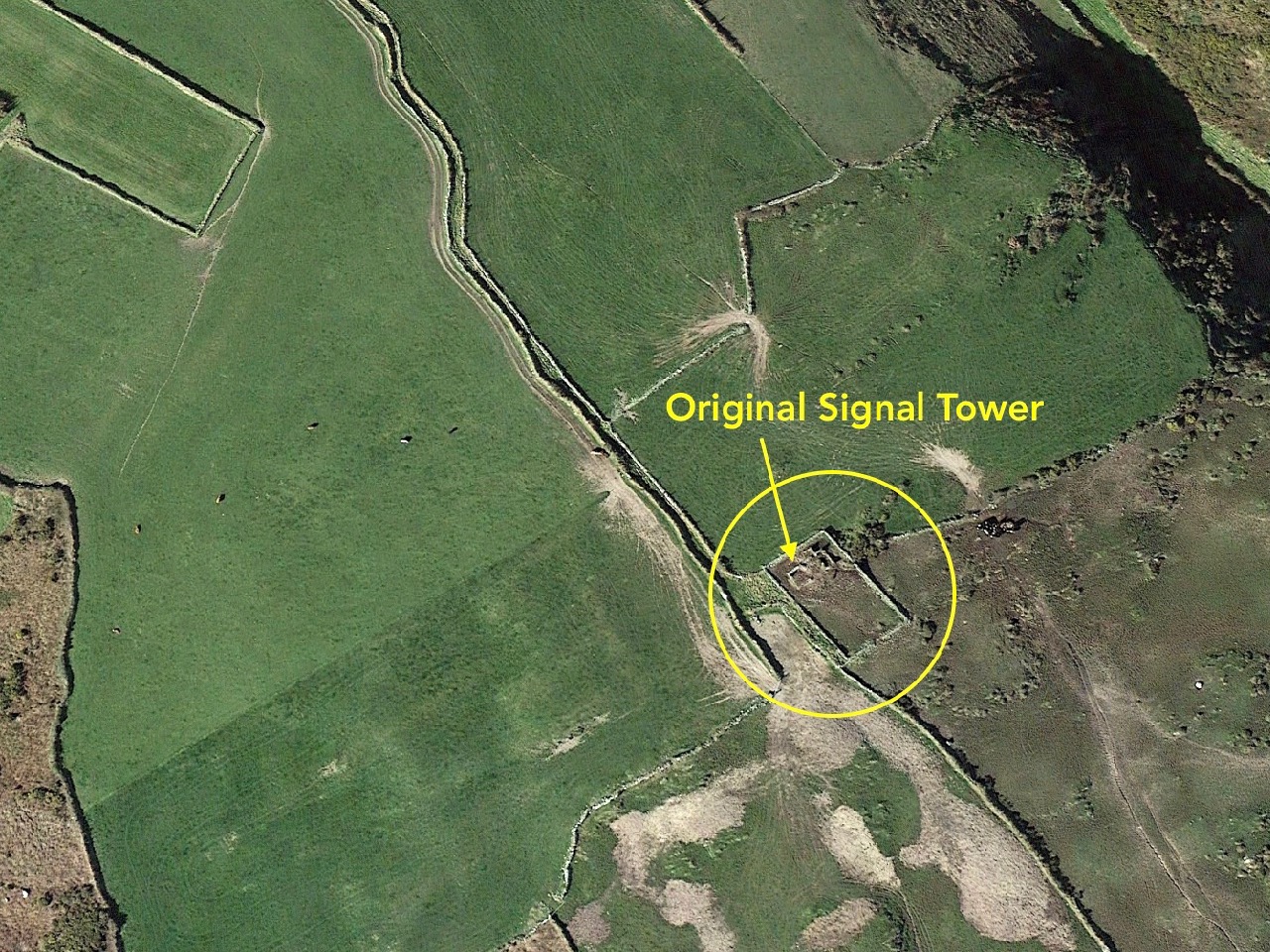

The header picture shows all that remains of the buildings of Downeen signal tower today. In the distance you can see Galley Head with its lighthouse. There was no signal station on Galley Head itself, the next in line to the east being at Dunnycove, in the townland of Ballyluck – this will be the subject of a future post. The aerial views above show the Downeen site: note the well-defined access trackway, a feature of all the locations we have visited to date. This signal tower has been changed and extended over the years, as can be seen by comparing the two OS maps below:

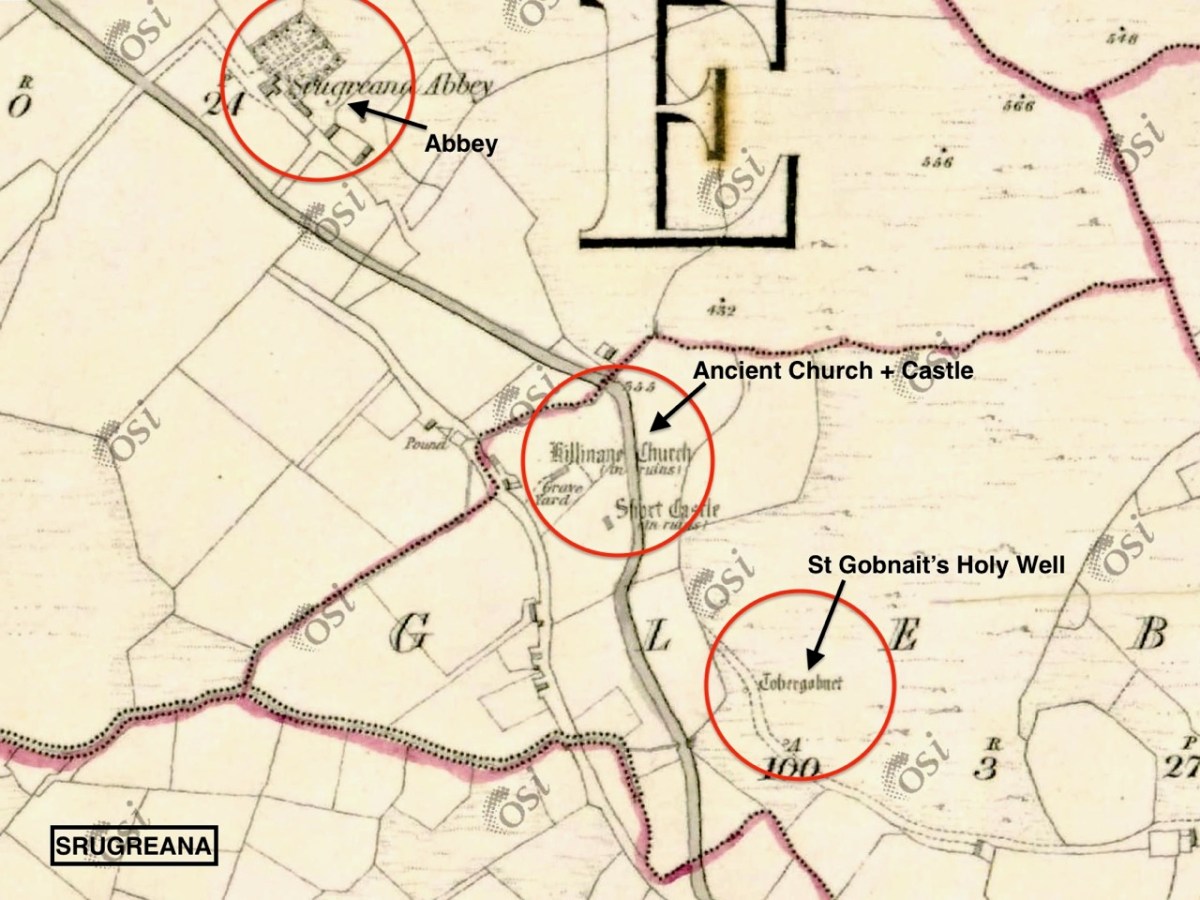

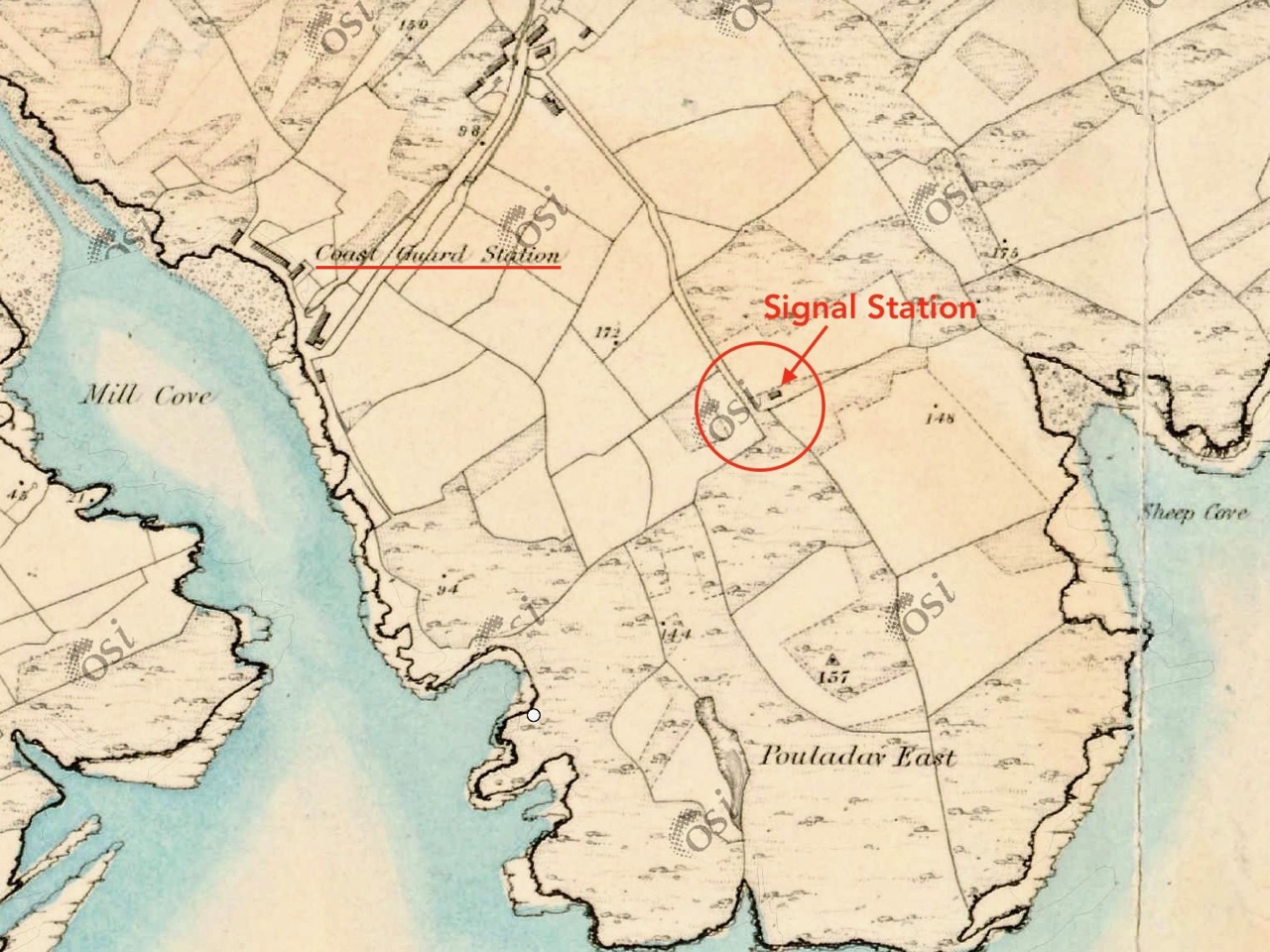

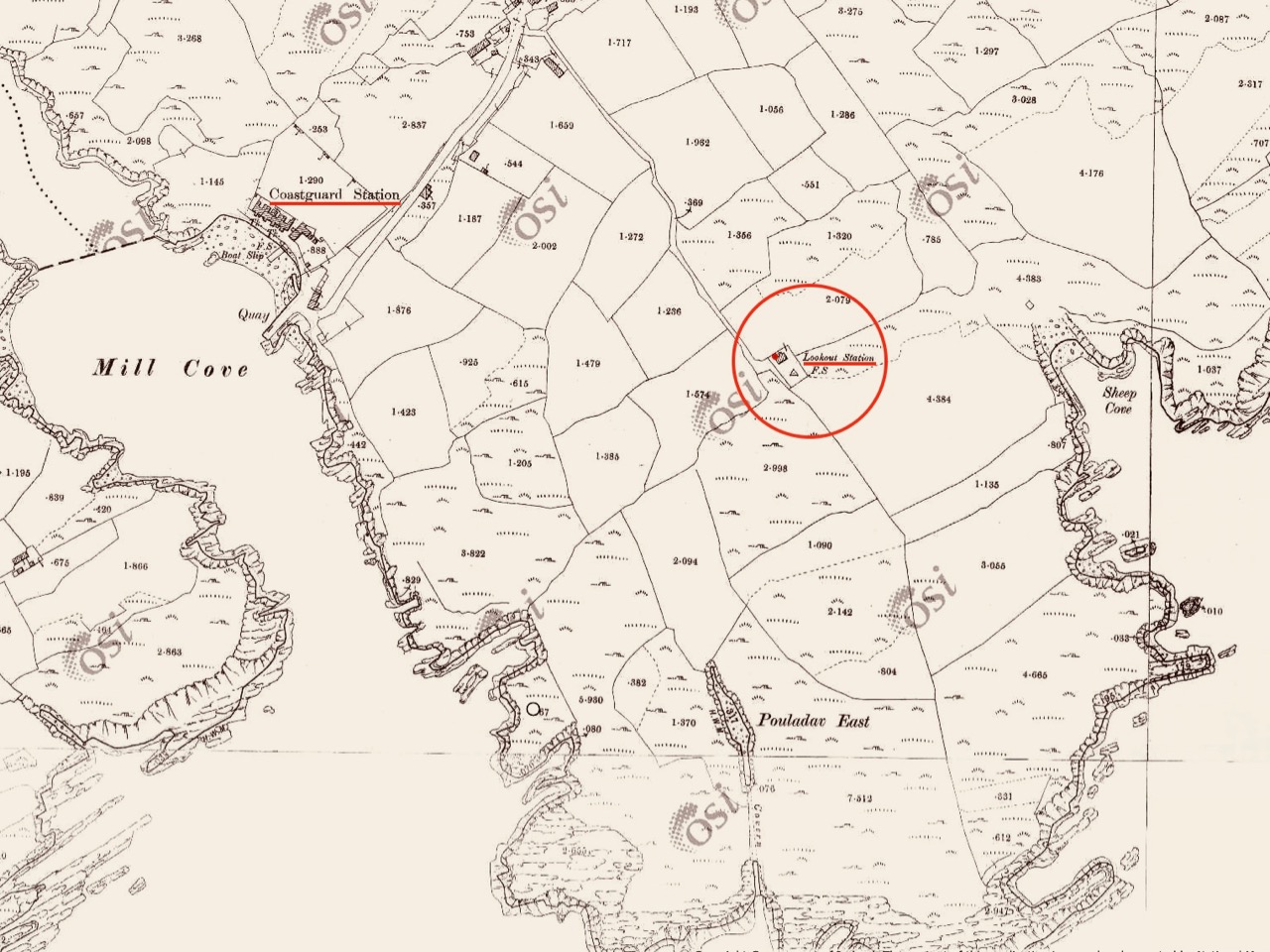

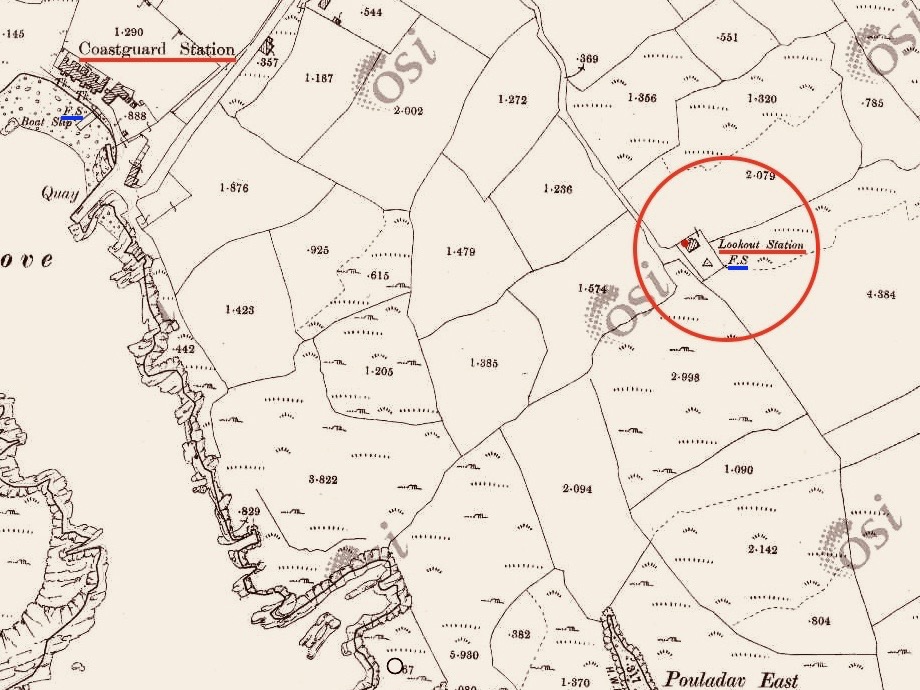

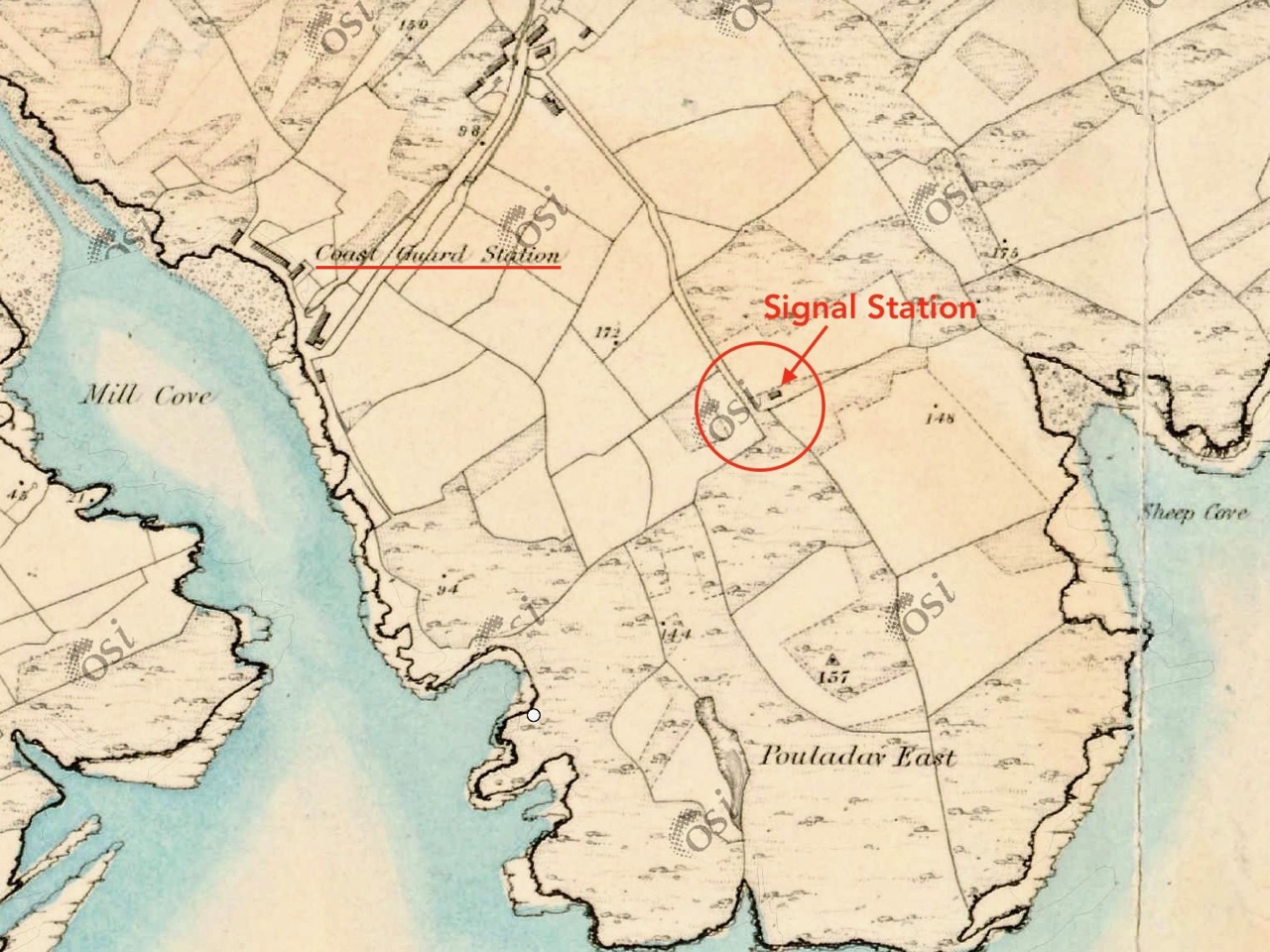

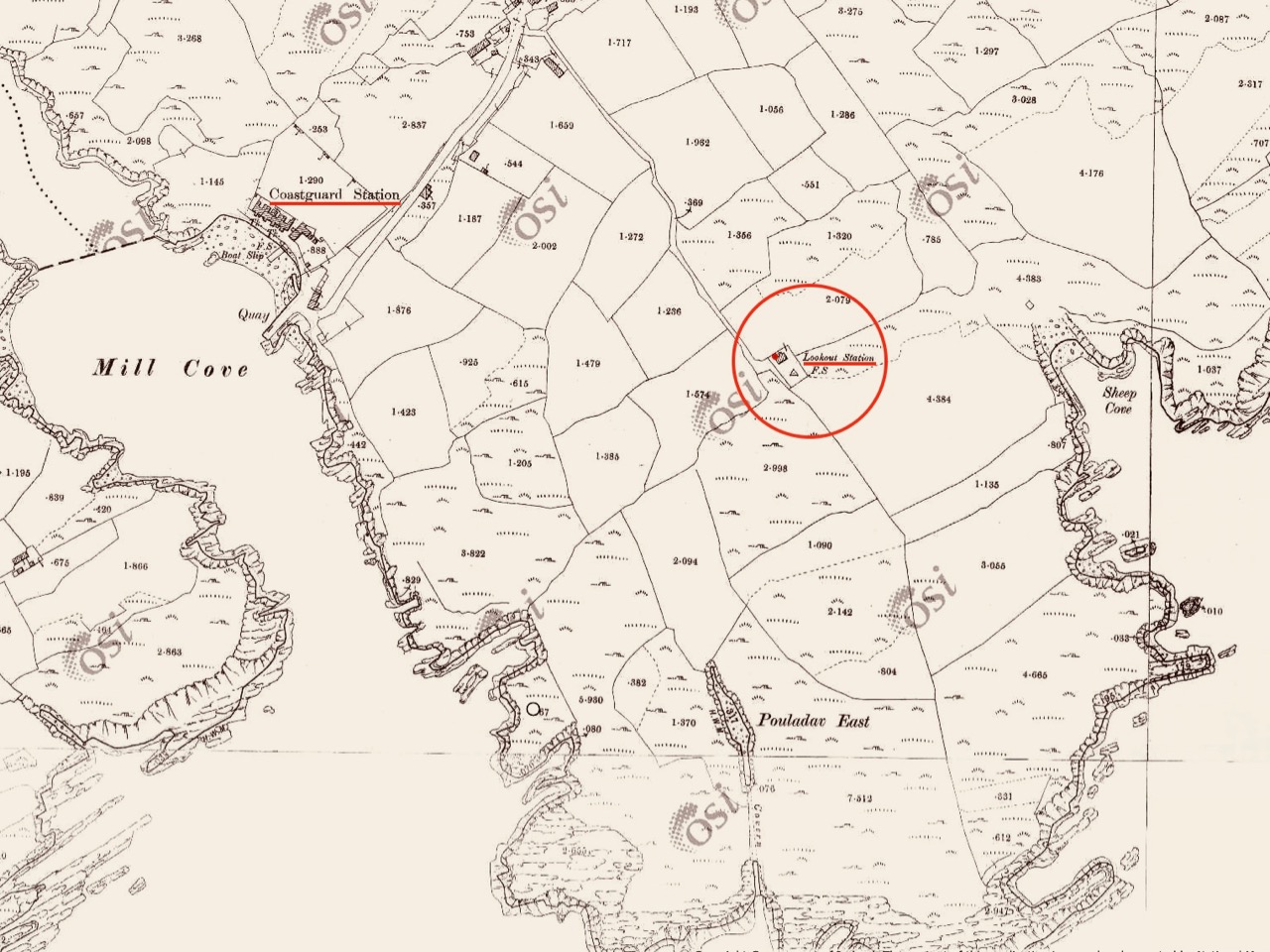

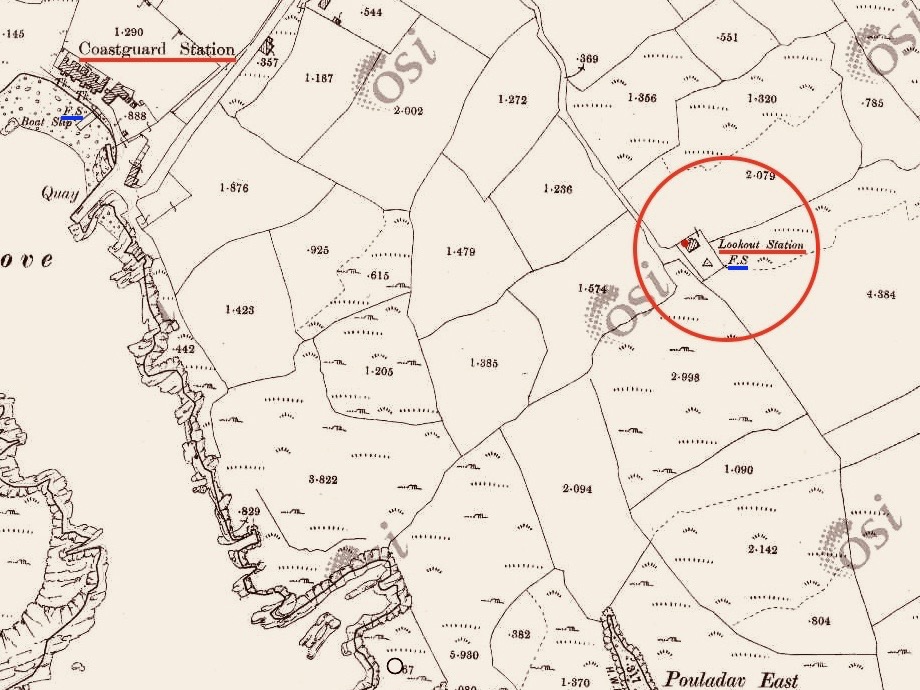

The upper map is based on the earliest 6″ survey which the Ordnace Survey carried out between 1829 and 1841. By that time, of course, the signal towers would have become redundant and this map shows a simple building and the trackway, with no label. The lower map is from the Historic 25″ survey, produced between 1888 and 1913. Here we see the site extended and the buildings altered, more in keeping with the present day aerial views. On this OS map the building is labelled as a ‘Lookout Station’ and there is also ‘F.S.’ shown, which I assume to indicate ‘Flag Staff’. This comparison exercise shows us how invaluable the Ordance Survey can be to historians in providing information often not documented elsewhere. Both maps show a ‘Coast Guard Station’ as the main feature of Mill Cove itself and this gives us the clue to the further incarnations of the original signal tower at Downeen. Here is an enlarged section from the 25″ map:

On this extract I have also underlined the two ‘F.S.’ indicators, which I take to mean flagstaffs – one at the Lookout Station, and the other at the ‘Coastguard Station’. Based on this I am putting forward the opinion that the original signal tower was taken over, extended or rebuilt for the use of the Coast Guards. I don’t have any other supporting evidence for this at Downeen, but at other stations I know this has definitely happened (either from written evidence or – more importantly – direct contact with local recollections). It certainly makes sense, as the towers were generally placed at the highest and best vantage points in the landscape – and had good access, verified by the surviving trackways.

The upper picture is taken from the Downeen signal station looking west – the sweeping vista is commanding. Two views of the access trackway show that it remains well defined by continuous masonry walls, but overgrown. Our only companions on our exploration regarded us with benign curiosity! Attempts to uncover a comprehensive history of Coast Guards and Coastguard stations here have not been rewarded so far – except to establish that, in Ireland, we should correctly refer to them as Coast Guards – not Coastguards. This information is taken from the Irish Government website (gov.ie):

In 1809 the “Water Guard” was formed. Also known as the Preventative Boat Service. The Waterguard was the sea-based arm of revenue enforcement who patrolled the shore. The Waterguard was initially based in Watch Houses around the coast, and boat crews patrolled the coast each night. It was under Navy control from 1816 to 1822, when it and riding officers were amalgamated under the control of the Board of Customs . . . in 1856 control of the Coast Guard passed to the Admiralty . . . In 1921, after Independence, the Coast Life Saving Service was established in Ireland . . . The duties formerly performed by His Majesty’s Coastguard (HMCG) were taken over by Saorstát Eireann (Irish Free State) and the Coast Lifesaving Service (CLSS) was established . . . In 1925 the UK Coastguard Act passed, formally defining its powers and responsibilities. This inadvertently used the single word ‘Coastguard’ for the first time, and affected all crown dominions . . . In 2000 Ireland re-established the Coast Guard as the original two-word variant . . .

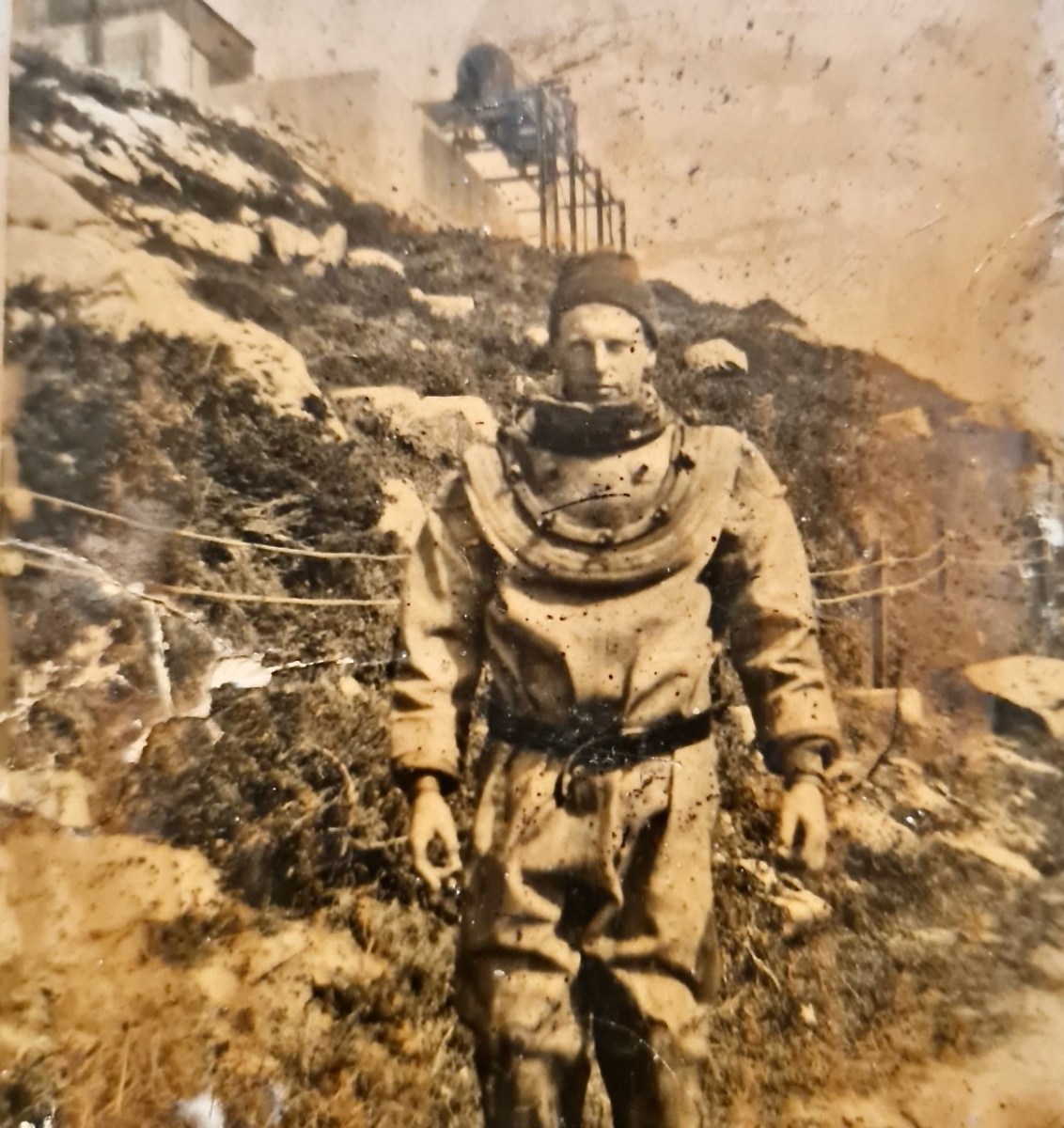

It’s fairly logical that the signal towers built between the 1790s and early 1800s to frustrate a French invasion of Ireland were still intact at the time of the Waterguard, and would have been ideal for the general purpose of watching the coast. (Above) – the ruins of the buildings at Downeen signal tower cum Coastguard lookout station as seen today. They enjoy the conceptual protection of being classified as a scheduled monument, but are unlikely ever to be more than crumbling vestigial stone walls. In their decay they command a poignant respect, and our imaginations can recreate the activities they may have witnessed. Here’s another quote, from the engrossing forum Coastguards of Yesteryear:

Nineteenth-century coastguards must have formed a close-knit group. Mostly ex-naval men, they presumably shared a sense of camaraderie . Often stationed as coastguards in remote spots, moved every few years to prevent them becoming too friendly with the locals, and often viewed with suspicion by those many locals with smuggling sympathies, coastguards were presumably drawn to marrying each others’ daughters. The more generous notion that “every nice girl loves a sailor” was only to develop later in the general population!

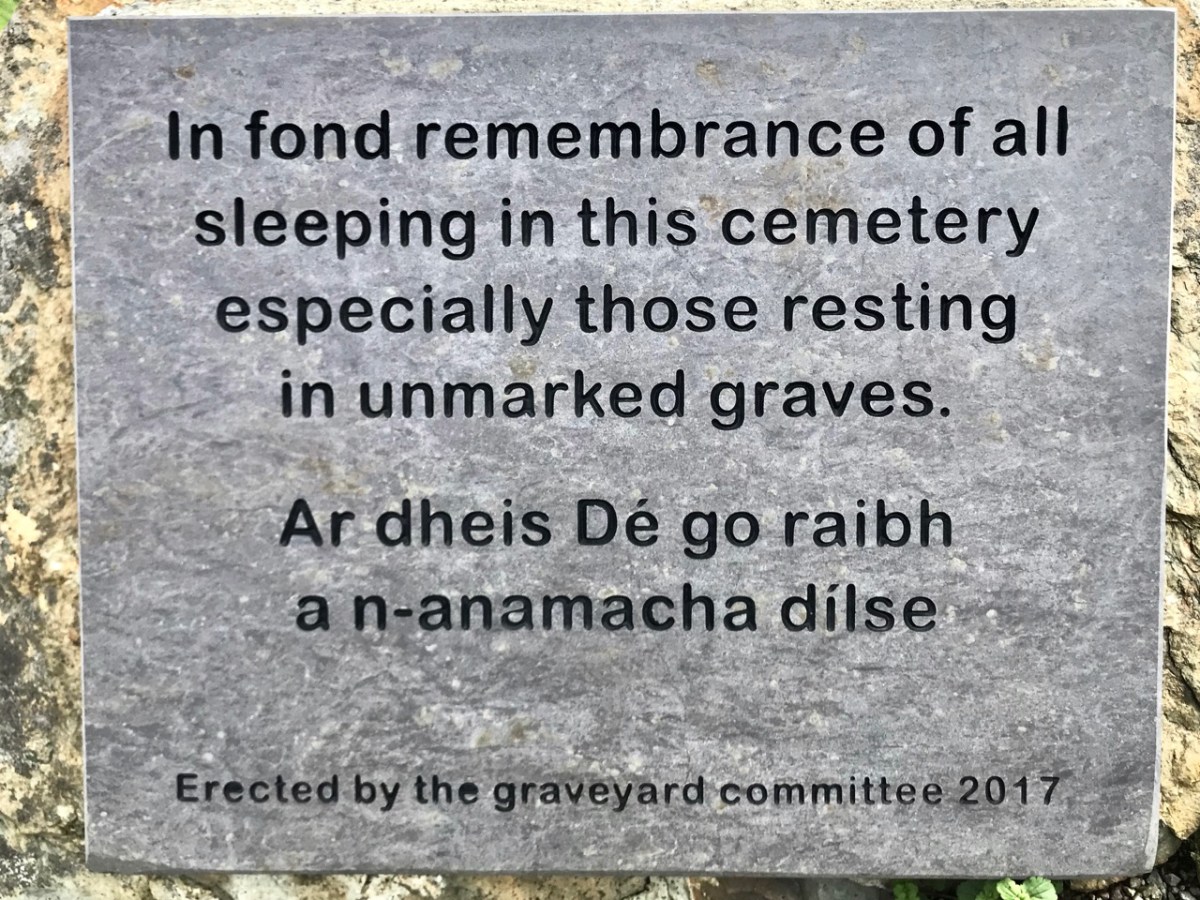

Notwithstanding the slight vestiges of its signal tower, Downeen has significantly more to offer in the way of history – worth a mention as it has led to some confusion in the story of this particular site.

We came across these two further ‘towers’ not too far away from the signal station site – also in Downeen. The first (upper) is classified as designed landscape – a belvedere. The second is a most intriguing tower house, a seemingly impossibly surviving clifftop ruin. On the day we visited, we were unable to get really close to either of these structures, but I was able to find a bit more about them on the internet, including a reference to the belvedere on the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage, where it is described as a ‘Signal Tower’ dating from between 1780 and 1820! In fact, further research has shown that this is a mis-attribution. Both these structures are connected to Castle Downeen. The tower house is described as possibly an O’Cowhig castle taken by crown forces in 1602 and approached by “a little drawbridge of wood”.

Here is the remarkably poised tower house at Downeen. The upper picture is courtesy of rowler21 via Google, 2020. I was delighted to find this small sketch (lower) by George du Noyer, titled Dooneen Castle, Rosscarbery, Sept 1853. Although almost 170 years have passed since du Noyer visited this part of West Cork – possibly in connection with his work for the Ordnance Survey – not much appears to have changed: perhaps the loss of part of the parapet. The ruin was apparently as precariously balanced then as it is now.

Downeen, with its lush valleys, old stone built settlement, former Coastguard station and this trackway serving a site formerly of great importance in the history of communications in Ireland is worth further exploration. As well as the 16th century tower house there are the abandoned and heavily overgrown remains of an 18th century ‘Country house’. This had a walled garden and the belvedere appears to be part of this. We are always surprised – and delighted – by the sheer volume of history that can be found in these out-of-the-way places, and remember – it is always worth talking to local people if you want to get under the skin of that history!

The previous posts in this series can be found through these links:

Part 1: Kedge Point, Co Cork

Part 2: Ballyroon Mountain, Co Cork

Part 3: Old Head of Kinsale, Co Cork

Part 4: Robert’s Head, Co Cork

Email link is under 'more' button.