Nead an Iolair – that is the house we live in, here in the townland of Cappaghglass, West Cork. That’s it, in the picture above, with a pair of eagles flying overhead… We don’t see them very often. Well, in truth, we haven’t seen them at all – this is a bit of photographic magic – and wishful thinking. Nead an Iolair – our Irish readers will know that this means Nest of the Eagles – is a perfect name for the site, suspended way up above Rossbrin Cove – a good lookout with higher ground behind: exactly the right environment for the big birds. There were undoubtedly eagles here once – and in various other parts of Ireland – but when and how many? As with most things nowadays, someone has carried out the research and there’s a study available online. It’s worth a read, but I can summarise the main points: analysis of place-names and documentary evidence from the last 1500 years enabled the following diagrams to be drawn up:

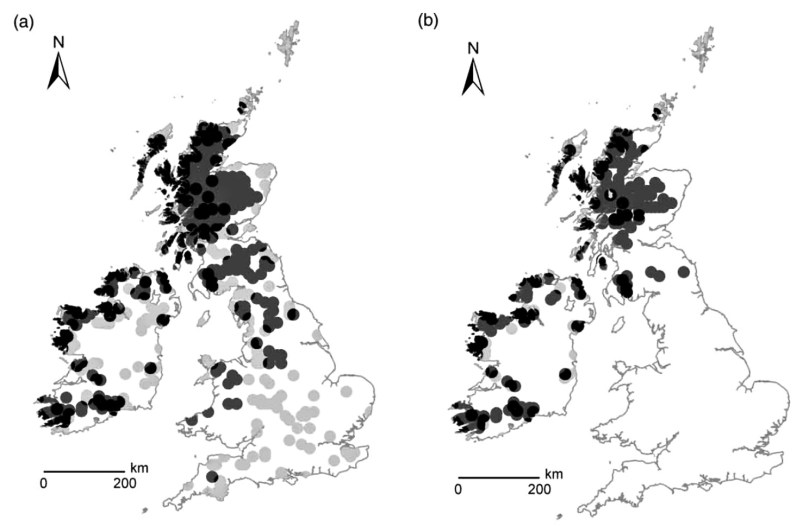

Data from The history of eagles in Britain and Ireland: an ecological review of placename and documentary evidence from the last 1500 years – Evans, O’Toole and Whitfield, RSPB Scotland 2012. Diagram (a) is 500AD and diagram (b) is 1800AD. The dots show Golden Eagle locations in dark grey, White-tailed Eagle locations in light grey and overlapping of both species in black

The diagram shows that White-tailed Eagles have lived here on the Mizen Peninsula 1500 years ago, and both species have been located a little further up the west coast as recently as 200 years ago. In 2001 fifty young golden eagles were released in Glenveagh National Park, Donegal, in an attempt to reintroduce the bird to Ireland. In a similar project to reintroduce white-tailed eagles, one hundred of the birds were brought from Norway to the Killarney National Park between 2007 and 2011, and up to September 2016 thirteen chicks have survived. The aim is to get at least ten chicks flying from their nests each year. Six white-tailed eagle chicks have flown from their nests in Ireland in 2016, making it the most successful year yet; one of these chicks was born near Glengariff, which is only just over the hill from us in terms of an eagle’s range. So we remain ever hopeful that the white-tailed eagles (sometimes known as white-tailed sea eagles) will soon make their way down here to Nead an Iolair – attracted, perhaps, by the name. We’d be very pleased to see them circling overhead – they are the largest birds on Ireland’s shores. Already our bird feeders attract avians of all shapes and sizes, and they generally get along fine with each other, although the smaller birds do make themselves scarce when Spioróg turns up!

A superb photograph of Haliaeetus albicilla – the white-tailed eagle or white-tailed sea-eagle, by Yathin S Krishnappa (via Wikipedia Commons). This was taken in Svolvaer, Norway – geographical source of the birds that were reintroduced into Killarney National Park within the last decade

Whenever we are on our travels we look out for the word Iolair (eagle) in place-names. We found one in Duhallow, a Barony in Cork County, just north of the wonderfully named Boggeragh Mountains. In fact we were alerted by signposts directing us to Nad or Nadd (nest) and found ourselves in a tiny settlement which was determined to point out its links with the eagles.

The village of Nead an Iolair in Duhallow, North Cork makes its associations with eagles very clear. The pub is named The Eagle’s Nest, and there is a fine sculpture of the bird sitting Nelson-like on a column beside it

Besides these features the village has a poignant memorial dating from the struggle for independence: a reminder of harsh realities still within living memory. The words that stand out are May God Free Ireland.

Back to the eagles and – in an interesting diversion into semantics – we noticed that the name over the door of the pub is in old Irish script and has introduced an additional character to the word Iolair – it looks like an ‘f’. Finola tells me that the use of the accent over that ‘f’ – which is known as a búilte – serves to silence the letter. In modern script it would be converted to ‘fh’: so fhiolair would still be pronounced ‘uller’. But we can’t find any precedent for using the word in this form. Perhaps an expert in Irish language can help us here…?

Regular readers will be aware that I am always on the lookout for links between Cornwall and the West of Ireland (and there are many). Interestingly, Nead an Iolair is one of them. Just outside St Ives, on the north coast of Cornwall, is a superb house, also called Eagle’s Nest. It was the family home of Patrick Heron, one of the influential St Ives School artists. When I lived in Cornwall I frequently passed by the house and was always impressed with its location – like us now, it is high up above the coast with a commanding view over the myriad small fields and out to the ocean. I always thought I would like to live there, because of that view… Now I have my own Eagle’s Nest – and I couldn’t be more content.