General Charles Vallancey, in the words of one of his biographers, ‘bestrode the world of Irish antiquarians for almost half a century.’ *

His origins are shrouded in mystery – although he is believed to have been born in Flanders to a French family, moved to England as a child, and attended Eton, there is no absolute proof of any of these facts of his early life. Even the date of his birth is contested – any time between 1720 and 1726. What is certain is that he joined the army, was posted to Ireland before 1760 as a military engineer, and spent the rest of his life, until his death in 1812, engaged with many aspects of Ireland, the country that one writer has called the great love of his life. Given that he had three wives (or maybe four) and twelve children (or maybe only 10, or maybe 15), that’s quite an assessment.

Dublin’s oldest bridge still in use, photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. It was designed by Vallancey and originally called the Queen’s Bridge, but re-labelled the Queen Maeve Bridge after independence, and eventually the Mellows Bridge

As a military engineer, Vallancey made real contributions: mapping and surveying large tracts of Ireland including the bogs and the canal systems; proposing a major transport route for Cork which, had it been realised, would have greatly aided trade and commerce in Ireland; building strong defences, such as on Spike Island; designing elegant bridges, and supervising the construction of an earlier version of the famous Dun Laoghaire Pier.

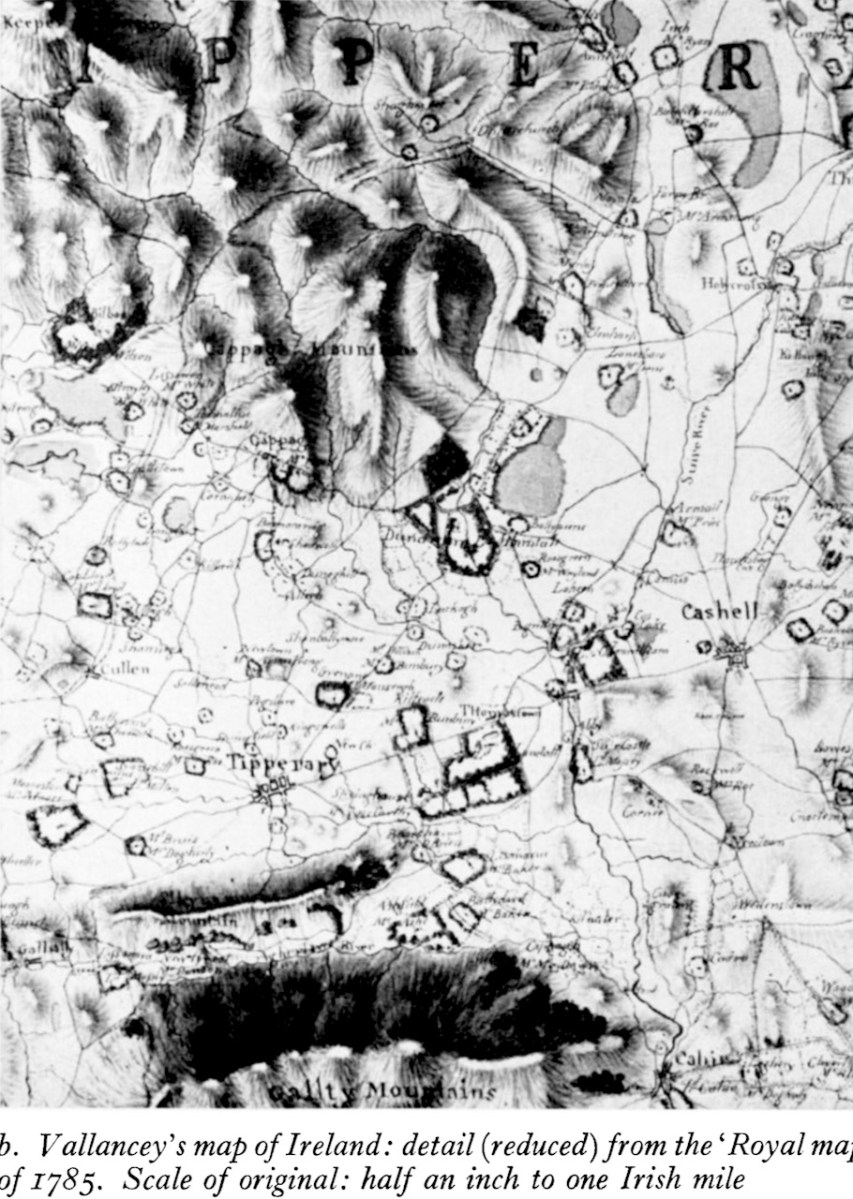

His cartographic achievements have been praised by experts – the extract above from a map of Tipperary is from Charles Vallancey and the Map of Ireland** by JH Andrews, our foremost cartographic historian who notes that Vallancey’s cartographic achievements were far from negligible. He made copies, in Paris, of the Down Survey Maps that had been lost to Ireland when they were captured by the French in 1707 en route from London to Dublin (unfortunately, those copies were destroyed in the Four Courts Fire of 1922).

But it was as an antiquarian that Vallancey made his greatest, and most controversial mark. He was a member, sometimes a founding member, of the serious societies of the time – the Dublin Society, the Royal Irish Academy and its important Committee of Antiquities, and the short-lived Hibernian Society of Antiquarians. Nevin tells us that at least three academic honours were conferred on Vallancey in the 1780s. He received an LLD from Dublin University in 1781 and became a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1784: he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1786. Even the French Academy of Belles-Lettres and Inscriptions honoured him.

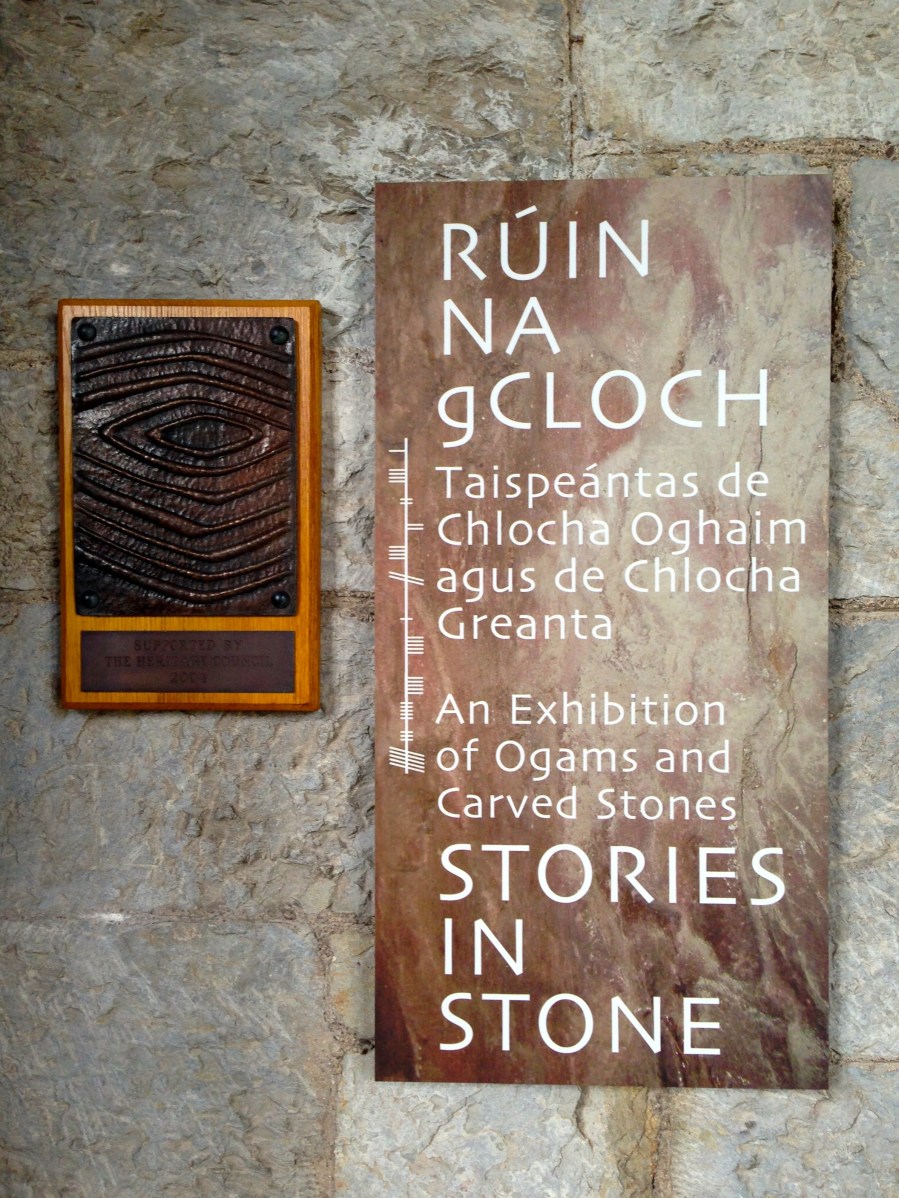

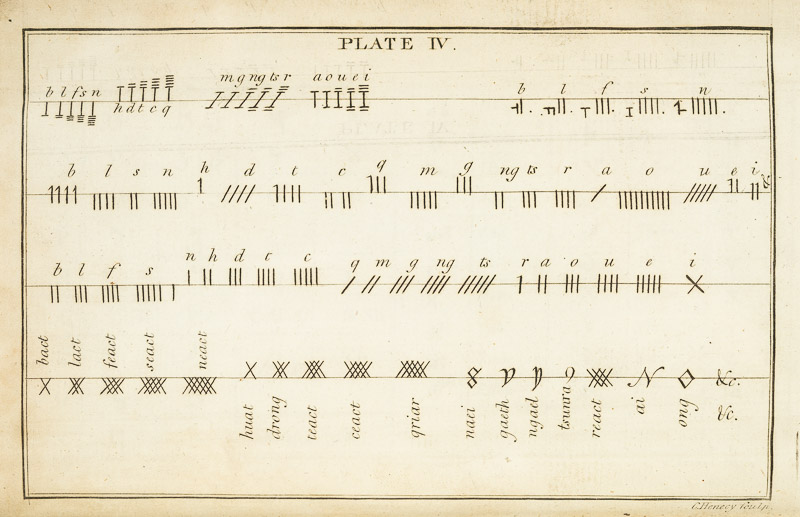

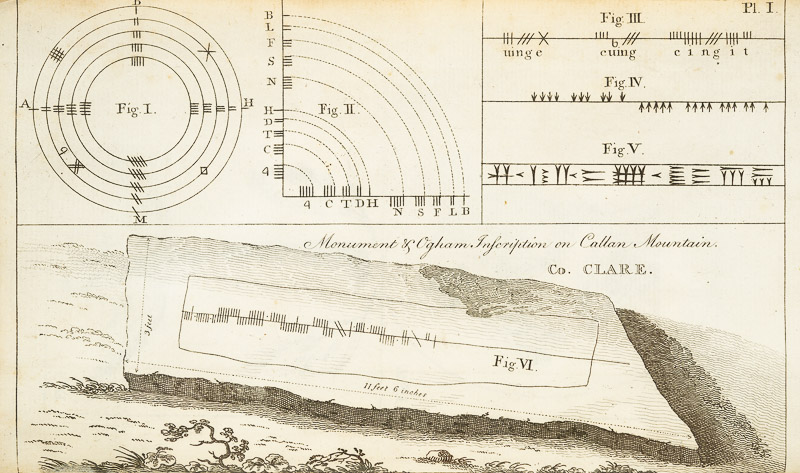

Unusually for the English and the landed classes living in Ireland at that time, he learned Irish. This allowed him to become familiar with the ancient manuscripts and annals which were being discovered and conserved at the time, and to translate some of them, including fragments of the Brehon Laws. It also led to his interest in Ogham, an alphabet used for inscriptions in stone in a form of Old Irish and he recorded examples of Ogham and reported on others.

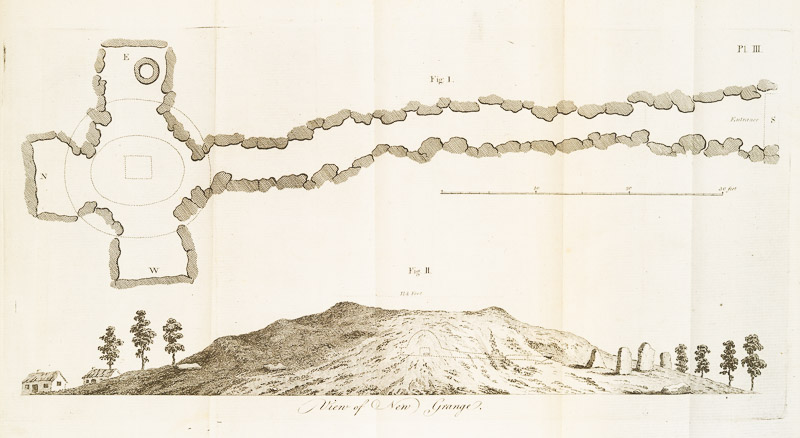

His interest in antiquities, fostered by his extensive travels around the Island, led him to record and draw many, including early plans of Newgrange, and to support the efforts of others, including Beranger, and perhaps Bigari, to record them. In some cases, Vallancey’s drawings are the only early records we have of some monuments.

Most importantly, Vallancey, even if he didn’t always get it right, strove to establish for Ireland and the Irish, a noble heritage, far from the view of most Englishmen at the time of a benighted people speaking a savage tongue. In this, he prefigured the work of Petrie, Wilde, Windel and others to show how the Irish past, and incredible heritage of archaeology, language and mythology, could stand against that of any civilisation.

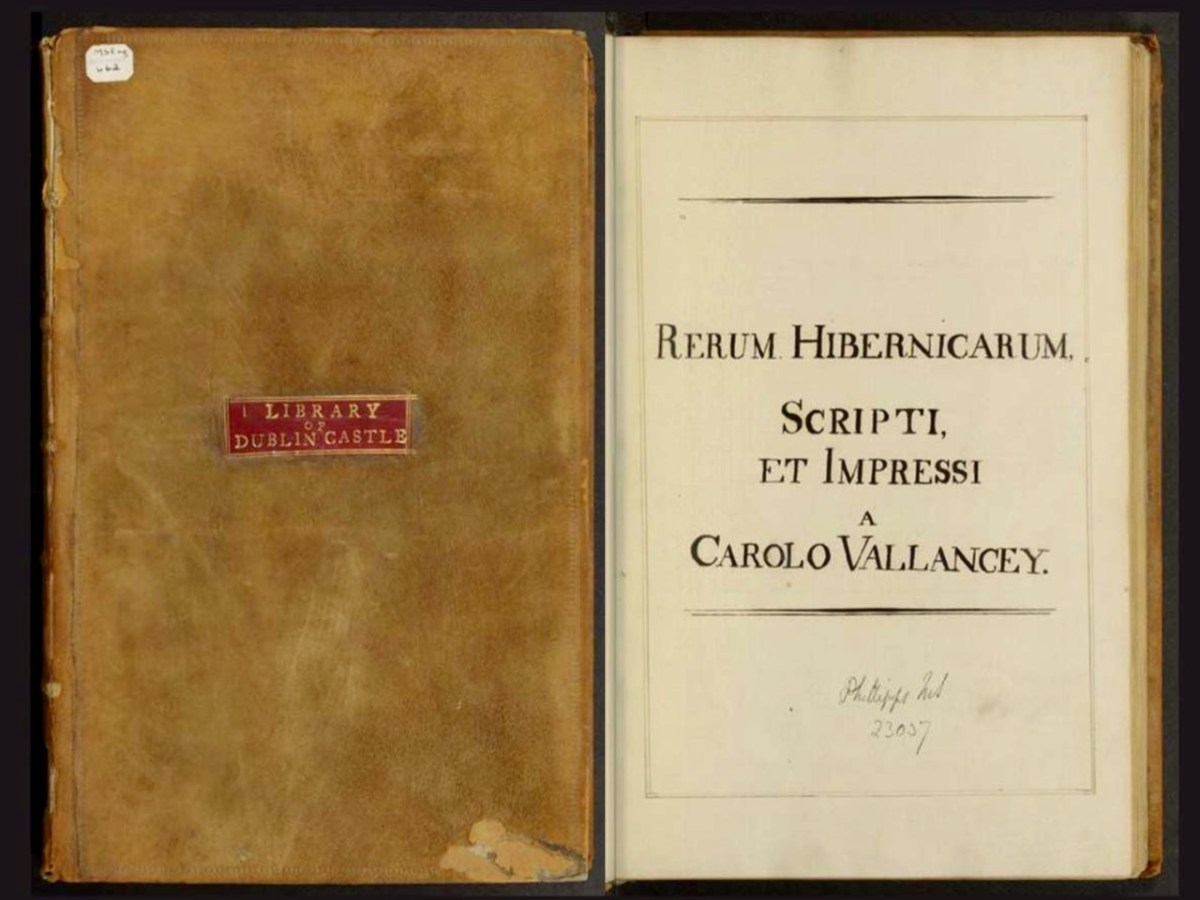

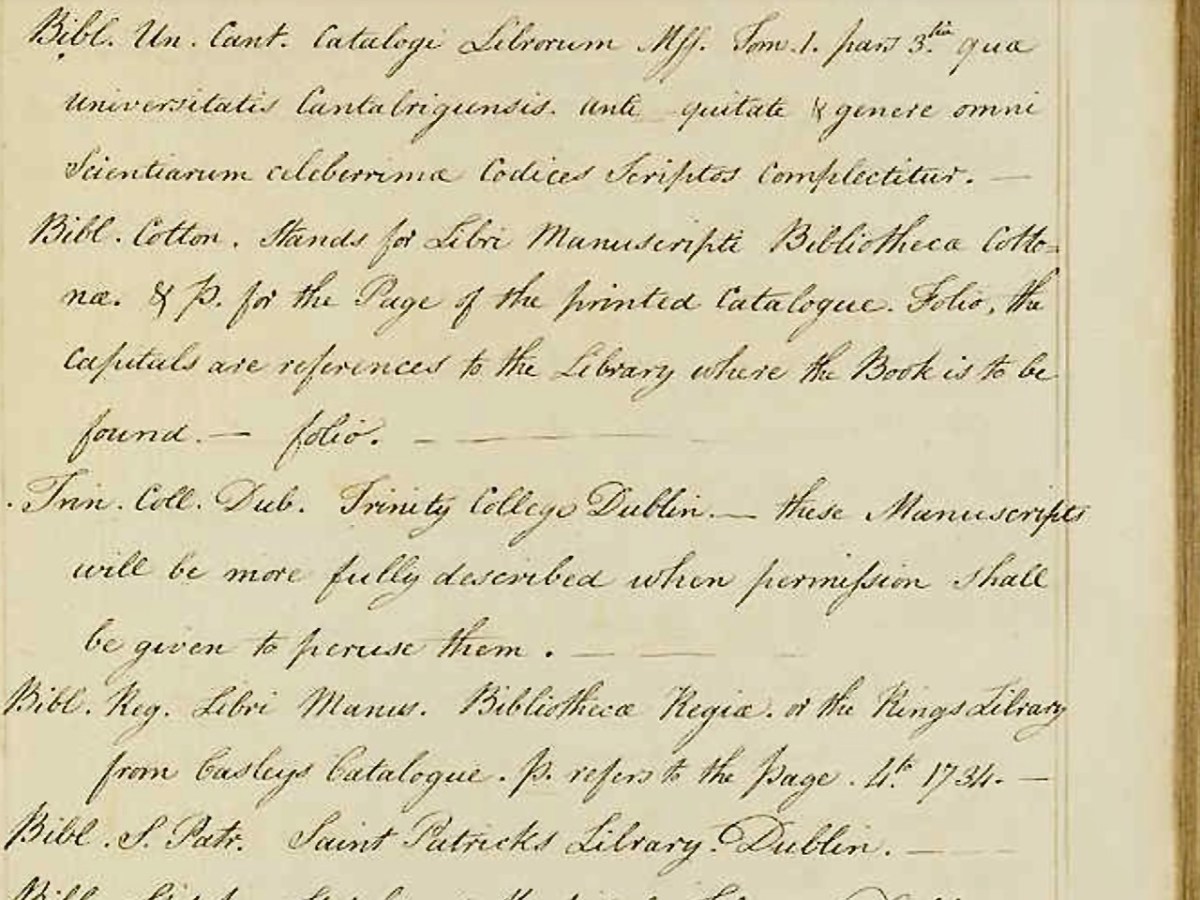

His least known but most important contribution to Irish scholarship was his Rerum Hibernicarum, Scripti, et Impressi. This is a handwritten

alphabetical list of material relating to Irish history divided into two sections; a list of manuscripts held in multiple archives and a supplementary list of printed works. The volume is undated, but as the most recent printed work cited is from 1777 the compilation was probably made shortly after this time.

Taking the long way home: the perambulations of Harvard MS Eng 662, Rerum Hibernicarum, Scripti et Impressi, by Charles Vallancey

Dr David Brown

The Rerum Hibernicarum disappeared – it had an interesting journey, entertainingly told by David Brown in his essay for the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland, in which a digital copy now resides. An incredibly valuable piece of research, it was the seminal book that initiated a more rigorous approach to Irish studies in the nineteenth century by providing sources for Irish manuscripts, folklore and language to the next generation of antiquarians. Brown says:

All four men, Larcom, Todd, O’Donovan and O’Curry, were committed members of the Royal Irish Academy, the institution Vallancey had co-founded in 1785. Together, this quartet placed Irish studies on a scientific basis and at the centre of Ireland’s main places of scholarship.

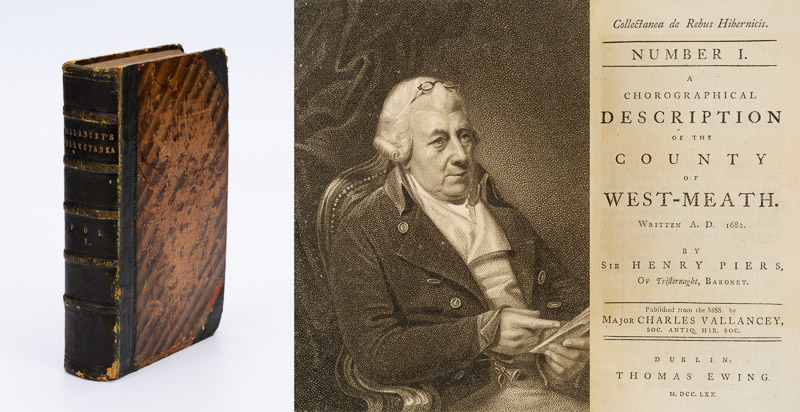

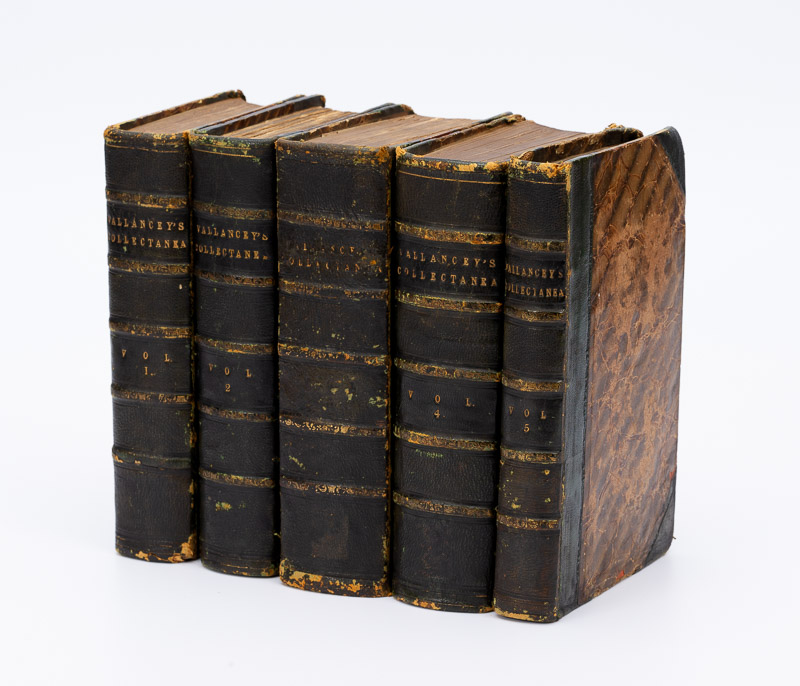

Vallancey’s best known work was his Collectanea de rebus hibernicis – Collection of Irish Matters. It is also his most complex and most characteristic – containing as it does a staggering variety of materials, much of it written by him. It contains work by others too, sometimes credited and sometimes presented as if written by Vallancey. He published it himself in limited editions, so that now it is very rare.

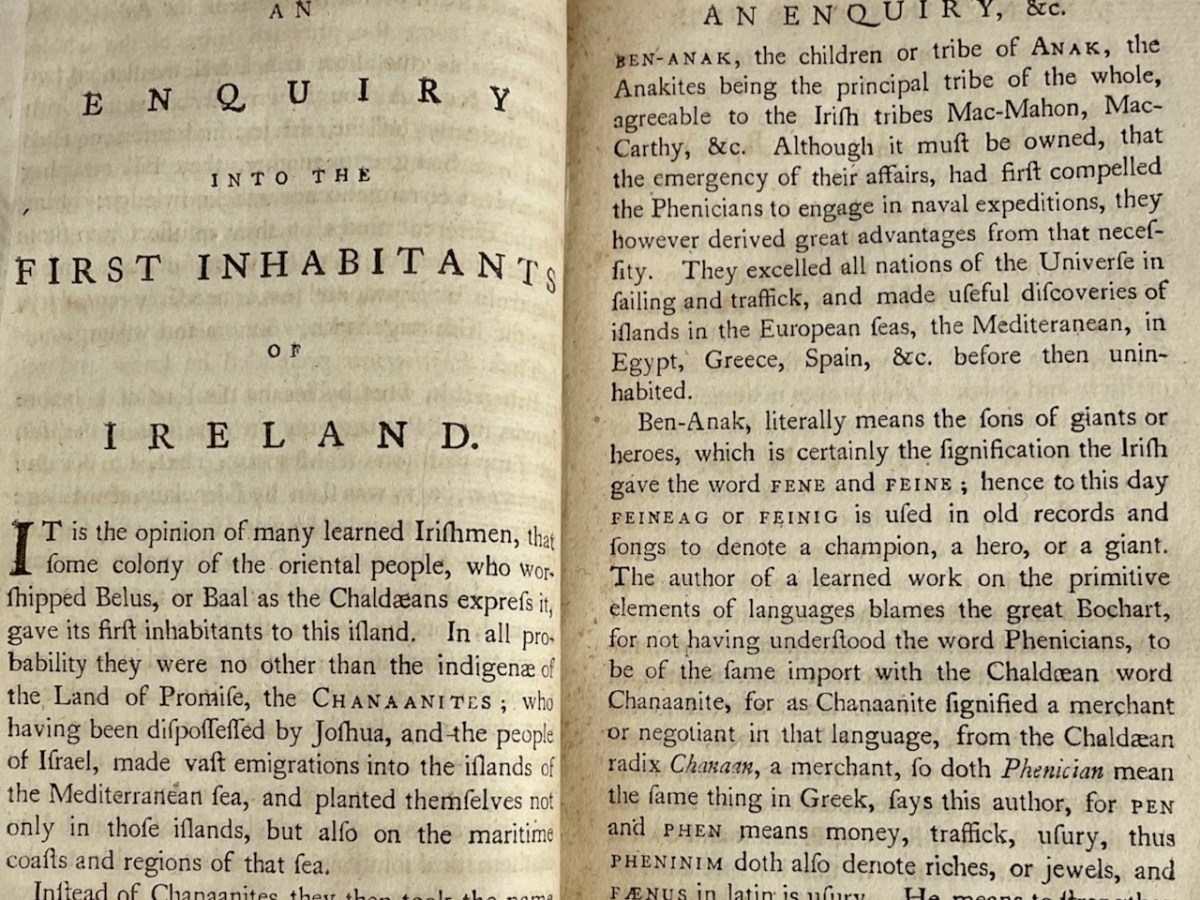

I am honoured to have been entrusted with a set to examine and write about, by Inanna Rare Books and have spent many happy hours browsing through the volumes. Reading it thus, from cover to cover, I began to see how enormously clever he was – and how obsessed, as he returns again and again to his favourite theme: that the Irish were a noble race descended from the ancient Phoenicians.

In this pursuit, Vallancey was not merely riding a personal hobby horse. In fact, he was very much in the mainstream of European intellectual thought. Vallancey believed that the Irish people were descended from the Scythians, Phoenicians, and Indians, and he used linguistic analysis, comparative mythology, and archaeological evidence to support his claims. In his essay, Phoenician Ireland: Charles Vallancey (1725–1812) and the Oriental Roots of Celtic Culture, Bernd Roling posits that Vallancey’s work, while ultimately based on speculation, reveals the powerful influence of ‘orientalizing’ models of history that were popular in the 17th and 18th centuries. He argues that Vallancey’s work is not simply a collection of outlandish ideas but rather a reflection of the enduring influence of ‘baroque’ antiquarianism and its commitment to finding connections between cultures and languages, even if these connections were ultimately based on speculation and incomplete understanding of the past.

Perhaps it was his enthusiasm for technology and the continuous journeys through Ireland required by his work that led Vallancey to find there the great love of his life of his life, namely Ireland herself. . .

In the eighteenth century Ireland was not the centre of the world. It was a land dominated and exploited by England, with a rural population who were regarded as barbarians at best by the gentlemen at home in the clubs and coffee houses of England’s cities. For them, the native language of the Irish was no more than an incomprehensible squawking that needn’t be accorded any further significance. Would it not, then, be a magnificent surprise, almost a humbling of Anglophile arrogance, if the Irish turned out to be the descendants of the ancient Chaldees, Phoenicians, Scythians and Indians, the crowning jewel in a chain of heroic acts reaching back into a prehistory, which was able to supersede any other chain of historical events? Would it not be a wonder if the Land of Saints and Scholars, with its ancient monuments, poetry and songs, were the final record of a primordial European people whose wisdom united the learning of the whole ancient East?

Yes, indeed, Vallancey, himself a bit of an outsider, was consumed with the need for that humbling of Anglophile arrogance. Unfortunately, as with anyone blindly obsessed with a cause, and simultaneously lacking self-doubt, this led him into many false conclusions and leaps of imagination in his interpretations of how Irish Gaelic related to ancient and oriental languages. His philological arguments were thoroughly debunked, starting almost immediately upon publication.

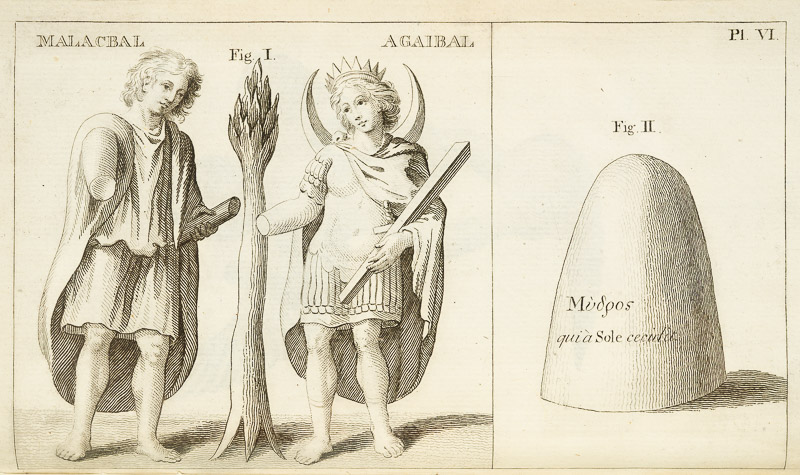

And it wasn’t just language – he had equally startling views about round towers, proposing that they were built by Scythians. He suggested that they were part of the “Scytho-Phoenician settlement of Ireland” and linked to ancient Chaldean religion. He drew on the work of other scholars to support his argument, citing the discovery of similar towers, called misgir or “fire towers,” in the Volga region formerly inhabited by the Bulgars. Vallancey also referenced Geoffrey Keating’s account of a druid named Midghe, who supposedly taught the Irish the use of fire during the third invasion by the followers of Nemed (from the Book of Invasions, a mythological origin story for Irish History). This association with fire, combined with the architectural similarities to the towers in the Volga region, led Vallancey to believe that the round towers served as observatories for an astral, or sun-worshipping, cult that had been brought to Ireland by the Phoenicians.

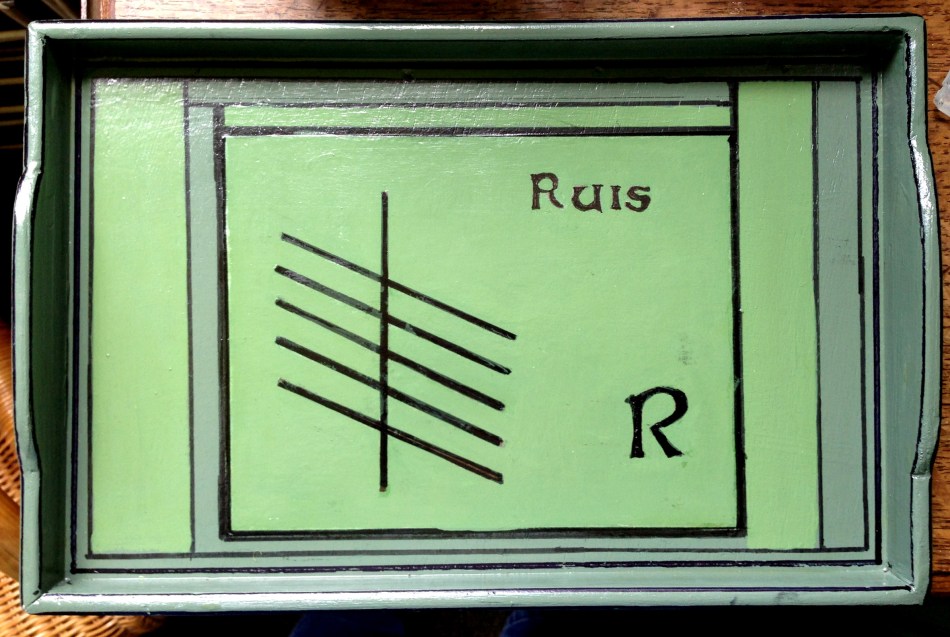

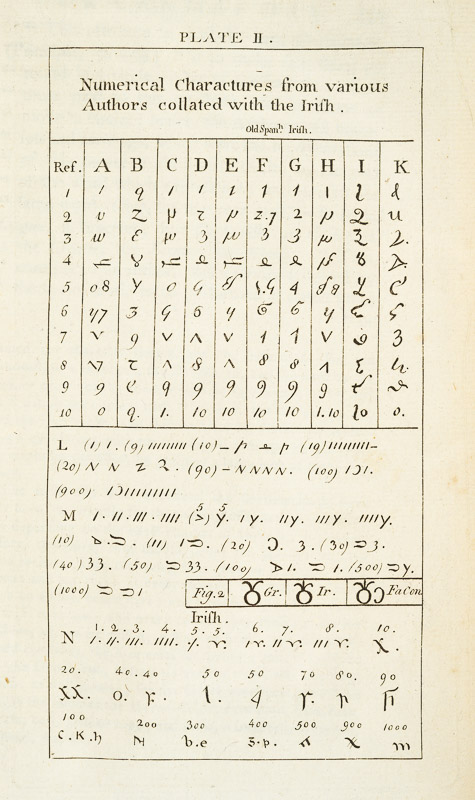

Similarly, with ogham, an early Irish script mainly found carved into standing stones, he argued that the word ogham itself was derived from Sanskrit, meaning ‘sacred or mysterious writing or language’ and pointed to the visual similarities between ogham and the Old Persian cuneiform script found at Persepolis as further evidence of an oriental connection. This view aligned with his broader theories about the druids as practitioners of a sophisticated astral cult with origins in Chaldea and connections to the Indian Brahmans

His research on ogham was extensive, including the study of ogham inscriptions and the publication of scholarly articles and drawings of ogham stones in his Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis. Next week, we will take a deep dive into that Collectanea. Meanwhile, I’ll try to figure out how to pronounce that word correctly.