Amanda started her blog, Holy Wells of Cork, in February and oh my goodness she already has over 100 wells documented. Not just documented – recorded, photographed, mapped, described, researched and written up in a charming cheerful style that’s a hoot and a pleasure to read.

Standard Amanda shot as she checks out St Laitiaran’s Well

Robert and I go along on her well-finding trips every now and then. Between accompanying Amanda, and wells we’ve gone to ourselves, we’ve visited about half the wells in her gazetteer. The sheer variety is astonishing, as also is the varying state of preservation. From muddy holes in the ground to gleaming and designed surrounds – holy wells come in all shapes, all sizes, and all conditions.

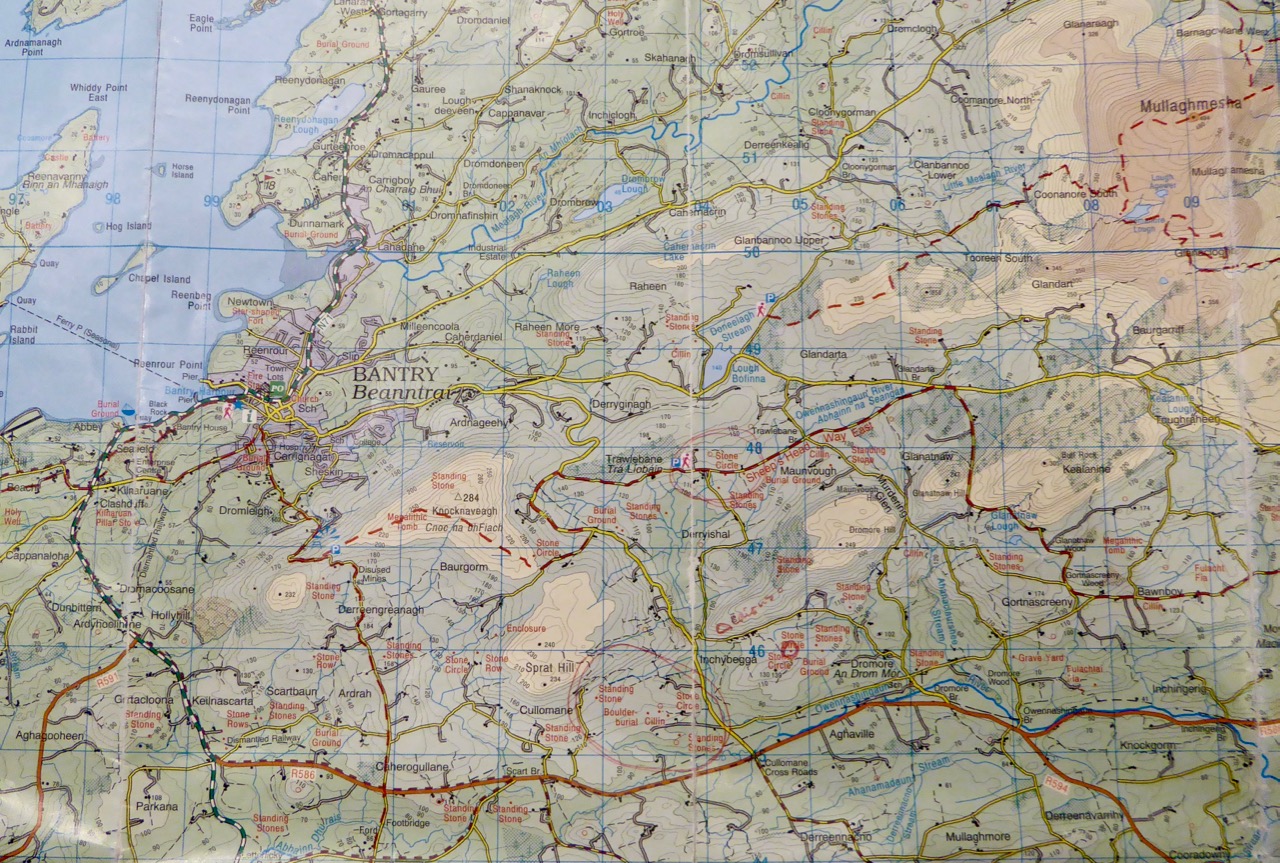

Duhallow – isn’t that a lovely word? It’s a lovely place too – a barony (part of Ireland’s old land division system) that occupies the northwest corner of the county of Cork. It’s mostly rolling hills and farmland, drained by the headwaters of the Blackwater River, with the Derrynasaggart and Boggeragh mountains to the south and the rich agricultural lands of Limerick to the north, while the Kingdom of Kerry lies just over the county border to the west.

Duhallow has its act together when it comes to holy wells – the local development committee has developed a Holy Well Trail. A brochure leads you around the trail and at each well is a detailed history of the well, the saints associated with it, the cures attributed to it, and the rounds and prayers to be undertaken.

Tubrid Well, Millstreet. Robert adds his mark to the cross inscribed by hundreds of pilgrims

Tubrid Well, Millstreet. Robert adds his mark to the cross inscribed by hundreds of pilgrims

At many of these sites mass is still said once a year and cups and bottles are provided so that you can drink, or take away, some of the water. The Tubrid Well outside Millstreeet is the largest and most active. While we were there people came and went and fresh flowers and candles were in evidence. This is a well that even has its own Facebook page!

A rag tree at the well of Inghne Bhuidhe

The well devoted to Inghne Bhuidhe (Inyeh Bwee, daughter of Buidhe, the Yellow-Haired) provided a complete contrast – out in the middle of corn fields, surrounded by a low wall and with a rag-festooned thorn tree looming over it. This one had a remote and tranquil vibe, suitable for contemplation.

My personal favourite was the Trinity Well near Newmarket, mainly because it was built inside a fulacht fiadh (pronounced full okt feeah) – that’s an ancient (possibly as far back as the Late Bronze Age) cooking place where stones were heated and then rolled into a trough of water. Over time, the used stones built up into a horseshoe-shaped mound that surround the trough – now re-purposed as a holy well. It was a marvellous testament to the timeless character of special places in the deep countryside.

Trinity Well, formed from an ancient fulacht fiadh

One of Duhallow’s wells is high in the Mushera Hills and dedicated to St John. The first photo in this post shows the location and extent of it. Back when the veneration of holy wells was at its peak, this one was the site of an enormous pilgrimage on St John’s Eve, June 23rd, every year. As with many such events the prayers and devotions of the daytime gave way to the partying of the night time and eventually the church acted to curb what they saw as the excessive debauchery of the occasion. Read Amanda’s account of the goings-on at Gougane Barra for an insight into the aprés-penance hooleys.

Tullylease had three wells, one devoted to Mary and another to St Beirechert (a saint whose name is spelled in a bewildering number of ways). The third well turned out to be something different – see below. The Marian well is thoughtfully stocked with holy water. Some of it is now in our bathroom to see if a few drops added to the bathwater will fend off the rheumatiz. So far, so good.

St Beirechert’s church has several interesting carvings: St Beirechert himself in an unlikely swallow-tailed coat and tricorn hat, several fragments and a wonderfully worked cross slab with interlace design.

We were intrigued to learn recently that this very cross was used as a model for the design of leather and fabric pieces for UCC’s Honan Chapel, an Arts and Crafts masterpiece, when it was being built a hundred years ago. I can’t show you a picture of that, as it’s undergoing painstaking conservation, but click here to see a modern use of the design!

The final well we saw at Tullylease wasn’t really a well at all but a bullaun stone – a big one. It’s supposed to cure headaches if you rub your forehead all around the rim, so here is Amanda, about to give it a try.

Our last stop was at a well for St Brigid. This one had a kind of cupboard containing a book in which visitors can write their prayers and ‘intentions’. It was fairly up to date, indicating recent visits.

In this post I have concentrated on the Duhallow wells, as examples of how one community has embraced this aspect of its heritage and created a wonderful experience for its residence and for visitors. For a detailed description of each of the ones I’ve mentioned here, browse through the North Cork section of Amanda’s Gazetteer.

In this post I have concentrated on the Duhallow wells, as examples of how one community has embraced this aspect of its heritage and created a wonderful experience for its residence and for visitors. For a detailed description of each of the ones I’ve mentioned here, browse through the North Cork section of Amanda’s Gazetteer.

But following a brochure and a map to wells that are tidy and well signed is not a fair representation of how you find holy wells in the field! In my next Good Well Hunting post I will invite you to come with us as we fight brambles, mud and neglect, as well as discover little gems still intact and visited in the deep countryside.