My eye was taken by an article in the Irish Times this week which stated that the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope have agreed to work towards a fixed date for Easter. Currently, that festival can occur anywhere between 22 March and 25 April – this year it will be an early one: Easter Sunday will be on 27 March. This has meant that, in Ireland, the Easter school holiday will last for three weeks, from St Patrick’s day (17 March – and always a day off school) until 4 April. Evidently the church leaders believe that a fixed date for all Christians around the world to celebrate Easter would be logical and practical. So much for logic – what about history and tradition?

It’s all about the sun and the moon, and the Vernal Equinox. That’s the point in the first half of the year when day and night are of exactly equal length. We are used to thinking of the equinox occurring on 21 March but this won’t happen again until the 22nd century! From now until 2044 the equinox will be on 20 March, then on the nineteenth. This is in part because our Gregorian calendar is inaccurate, but also because the Earth’s axial precession is gradually changing. In 325 the Council of Nicaea established that Easter would be held on the first Sunday after the first full moon occurring on or after the Vernal Equinox, but that was taken to be 21 March. You can begin to see the complications…

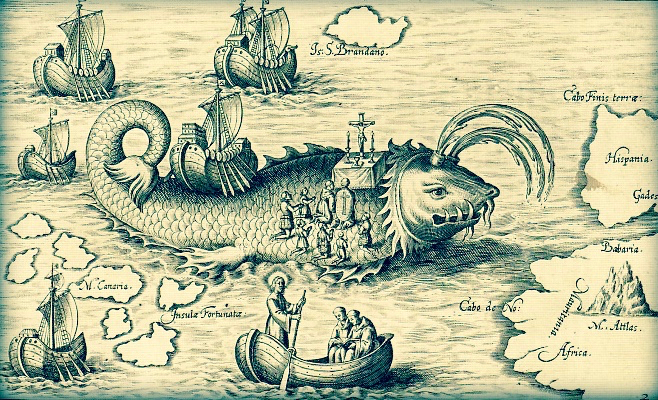

As you might expect, Ireland has had a lot to say about all this. The early church here, established by Saint Patrick, didn’t necessarily agree with the Roman church over certain issues, including the date of Easter. Matters came to a head in 664 when a synod was convened in Whitby, Yorkshire attended by delegates from the Ionian tradition and the Roman tradition. The Ionians were led by the Irish Saint Colmán, Bishop of Lindisfarne. They supported the older traditions, but the debate was won by the Romans and Saint Colmán resigned his post and returned to Ireland, where he founded abbeys in Inishbofin and Mayo and – presumably – continued to celebrate Easter in the ‘old way’.

The situation today is still confused. While Roman Catholic and Protestant churches use the ‘Alexandrine rules’, agreed in the 7th century and adapted when the Gregorian calendar was introduced (1582), Orthodox churches generally follow a method based on the earlier Julian calendar but, in fact, there are different systems used by the many different branches of Orthodoxy around the world so the Easter festival in any year may be celebrated on varying dates in divergent places.

Let’s look at tradition, especially in Ireland. Although the churches here did eventually conform to the Roman calculations, there was always some dissent. Folklore tells us that the monks on the Skelligs – isolated rocks off the Kerry coast which housed a monastery back in medieval times – followed a calendar which was several days behind the rest of the country – this sounds as though they were still basing themselves on the Julian system. This was useful, however, if you missed out on getting married before the beginning of Lent (you couldn’t marry during Lent): the period we are in now – between Little Christmas (6 January) and the beginning of Lent – was in Ireland always the most popular time for weddings. ‘Going to the Skelligs’ was a joking expression used unkindly against confirmed bachelors and spinsters.

From Danaher The Year in Ireland – Mercier Press 1972:

In much of the south-west of Munster there is a vague tradition that the festival of Easter was celebrated a week later on the island sanctuary of Sceilg Mhichil than on the mainland. Whether this tradition is a distant echo of the ancient controversy on the date of Easter is a matter of speculation, but it did give the occasion of another form of disapproval of the unmarried. These had lost their chance of marrying this year on the mainland, but they could still be married on the Skellig, and steps must be taken to send them there… All over County Kerry, in parts of west County Limerick, in much of County Cork, especially along the coast, and in west County Waterford the negligent were greeted, in the first days of Lent, with a barrage of chaff and banter. ‘You’re off to the Rock, I suppose?’ ‘Don’t miss the boat!’ ‘Is it Mary or Katie you’re taking on the excursion’ etc etc. The victims had to grin and bear it… In many places the custom was carried further, and local poets were encouraged to compose verses on the occasion, verses which told of a grand sea excursion to the Skelligs, praised the splendid vessel which would take the party there and gave a long list of the participants, linking together the names of the bachelors and old maids as incongruously as possible. These verses – most of them mere doggerel – were written out and circulated about the parish so that all might enjoy them, and were sung to popular airs, often in the hearing of those lampooned in them… The custom has in more recent times taken the form of large posters, giving details of the ‘Grand Excursion’ with a list of the couples taking part in it. These notices were hung in prominent positions on the first Sunday of Lent, where they might be read by all on their way to church… In south-east County Cork the Skellig joke appeared in its most extreme form. Here bands of young men went about on Shrove Tuesday evening, and if some inveterate bachelor ventured out and fell into their hands he was bound with ropes and had his head ducked under a pump or in a well; this drenching was called ‘going to the Skelligs’

The Skelligs have been in the news recently, as the setting for a scene in the new Star Wars film: The Force Awakens. Filming on the historic site provoked considerable debate and discontent among archaeologists and conservationists. Despite our own reservations, Finola and I went to watch the film in Vancouver and – although we had to wait until the very end (the Skelligs appear only in the last scene) – we were delighted to see one of the West of Ireland’s most magnificent seascapes on the big screen – and in 3D!

Shrovetide is nearly upon us. If you haven’t arranged your pre-Lent weddings yet don’t forget there’s always the Skelligs!