The enigma begins around 1874, on Cape Clear – the southernmost piece of inhabited soil on the islands of Ireland. Land here is hard won, and the stony fields are laboriously cleared using human power and – most likely – donkey power to improve prospects for grazing and tillage. In this year a narrow field in the townland of Croha West is being improved: the farm belongs to Tom Shipsey. His men – Dónal O Síocháin and Conchúr O Ríogáin – turn up a stone with strange markings on it, reportedly together with ‘shards of old incised pottery’, although these latter have never been traced.

The enigma begins around 1874, on Cape Clear – the southernmost piece of inhabited soil on the islands of Ireland. Land here is hard won, and the stony fields are laboriously cleared using human power and – most likely – donkey power to improve prospects for grazing and tillage. In this year a narrow field in the townland of Croha West is being improved: the farm belongs to Tom Shipsey. His men – Dónal O Síocháin and Conchúr O Ríogáin – turn up a stone with strange markings on it, reportedly together with ‘shards of old incised pottery’, although these latter have never been traced.

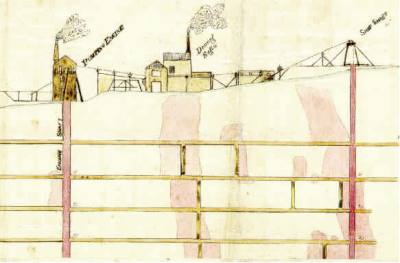

Header: looking towards the townland of Croha West, where Thomas Shipsey and his men discovered the travelling stone. Above left – records from the Shipsey family dating back to the 1800s. Above right – possibly the earliest drawing of the Cape Clear Inscribed Stone, included in Michael J O’Kelly’s article of 1949 in the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Journal

At this time the Curate on Cape is Revd John O’Leary. We might reasonably assume that he takes an interest in the stone and has it set up somewhere to show off its curious and undoubtedly historic decoration. We do know for sure that, when he leaves Cape Clear in 1877 to take up the curacy of neighbouring Sherkin Island, the stone goes with him and becomes a feature in his garden there. It does not, however, accompany him to Clonakilty whence he is transferred to become Parish Priest and Monsignor in 1881: instead it languishes on Sherkin, benignly fading into the undergrowth. Years later – in 1945 – the stone is ‘accidentally rediscovered’ by the then incumbent, Rev Fr E Lambe. Presumably recognising its probable significance he has it shipped off to University College Cork where it is received by Professor Seán P Ó Ríordáin.

1902 World’s Fair, Cork – now Fitzgerald’s Park and the setting for Cork Public Museum

Close to the University grounds in Cork is a residence built by Charles Beamish in 1845 at the cost of £4,000 on land purchased from the Duke of Devonshire. Beamish has the grounds laid out with a variety of shrubs and trees, and due to their density the grounds become known as The Strawberries and the house as The Shrubbery. In 1901 the house and grounds are taken over by Incorporated Cork International Association and used as the venue for the great World’s Fair of 1902. Following this the grounds – now known as Fitzgerald’s Park – are donated to Cork Corporation for recreational use by the public. Eventually The Shrubbery is converted into Cork’s Public Museum which opens in April 1945, under the auspices of UCC: the first Curator is Michael J O’Kelly. The Cape Clear Inscribed Stone completes its travels (for now) and is on permanent display in the Museum.

The highest point on Cape Clear is Quarantine Hill – the trig point can be seen as a ‘pimple’ in this photograph, taken from the north side of the island

There’s a prequel to this story of the travelling stone. We have seen that it was unearthed on Farmer Shipsey’s land in 1874. Apparently this isn’t where it started out. O’Kelly (who became head of the Archaeology Department at UCC in 1946) wrote a monograph on the stone for the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society in 1949 (volume 54 pages 8 – 10):

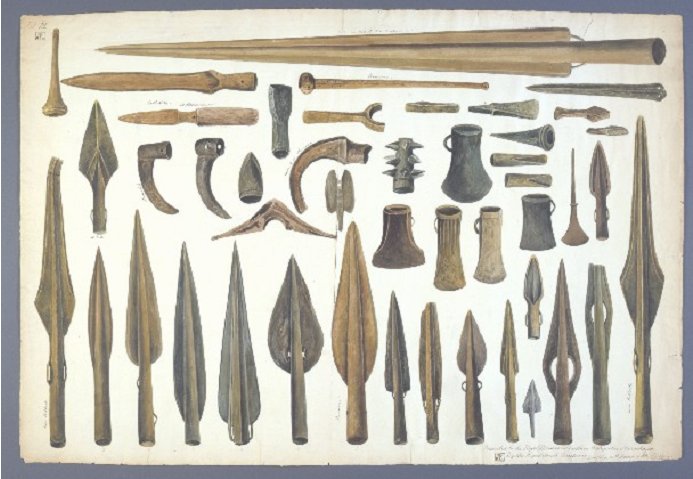

…The motifs clearly belong to the passage-grave group of carvings and can be paralleled at Newgrange, Bryn Celli Du [Wales], Gavr’ Inis [Brittany] and elsewhere. The stone is therefore an important discovery and because of this, the lack of information about the nature of the site on which it was found is all the more disappointing. At this stage only a few vague traditions concerning its finding could be gleaned in the district. The statement of one old man that ‘a mound of stones was being cleared from a field’ may possibly indicate a cairn and if such were the case, the decorated stone may have formed part of an underlying tomb chamber. There is also some reason to think that fragments of pottery were found, though none has survived. This may be a further hint that the stone was associated with a burial. With reserve, it might therefore be assumed that the structure, whatever its exact nature, was erected by a group of passage-grave folk who either by accident or design came to land on this island off the coast of Cork…

This little narrative sowed the seed that the stone might be connected to a passage grave. If so, this would probably date the carving to some five thousand years ago. But, surely, there should be some trace of the passage grave itself if this is the case? No such traces could be found in the townland of Croha West.

Spectacular views from the prehistoric site on Cape Clear, both looking north towards the mainland

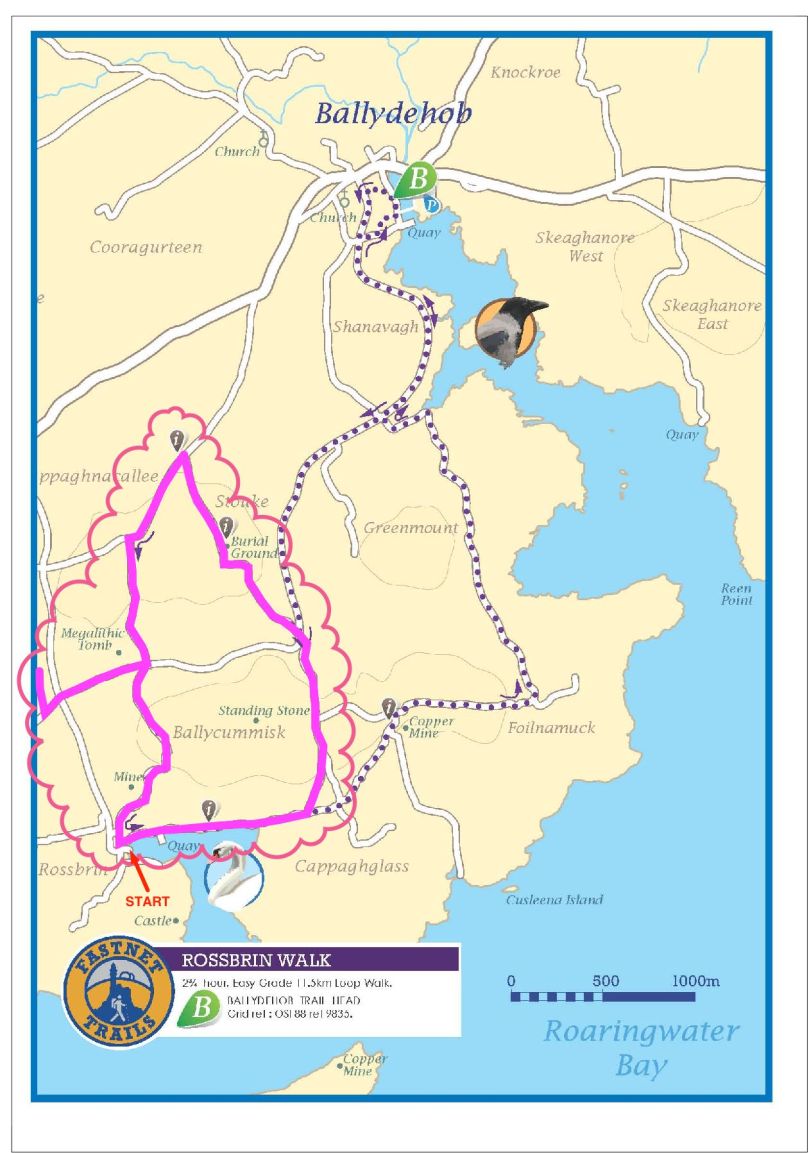

We move forward to 1984 when four archaeologists (Barra O Donnabhain, Mary O’Donnell, Jerry O’Sullivan and Paddy O’Leary) explored the wider area and discovered, on the very summit of the island, the ruins of a prehistoric structure. This site, 533 feet above sea level, is in the townland of Killickaforavane and is known locally as Quarantine Hill. At this time the island was investigating the possibility of producing electricity by wind power: hitherto electricity to some properties was provided by a diesel generating system which had been in place only since 1969. The obvious efficient place for wind generation was the highest point and plans were laid for setting up two SMA Regelsystem Gmbh 33w turbines (which began operation in 1987). In preparation for this installation an archaeological survey of the immediate area was carried out by Prof Peter Woodman and Dr Elizabeth Shee. Paddy O’Leary and Lee Snodgrass were also present at that time. The collective view seemed to indicate that the structure could, indeed, have been a small passage grave.

Probably the chamber of a 5,000 year old passage grave, Killickaforavane, Cape Clear

The wind turbines were sited a little distance from the prehistoric remains and have themselves become archaeology of a more industrial nature. While in use they generated 90% of the island’s demand during favourable winds (force 3+). The corrosive effects of the Atlantic climate – in particular the wild south-westerly gales – rendered the mechanisms beyond repair after some ten years; a submarine cable bringing electricity from the mainland (8 miles away) arrived in about 1995. For a short time the systems operated in tandem and produced sufficient power to feed back to Ireland’s National Grid. According to a letter to the Irish Times by Séamus Ó Drisceoil, who was manager of the island Co-op at the time of the installation …the Cape Clear system is credited with providing the first concrete evidence for the viability of wind energy in Ireland…

Tomorrow’s archaeology: the pioneering – but now defunct – wind generating system on Quarantine Hill, overlooking the passage grave site

Once the concept of the island supporting a five thousand year old passage grave on its summit has been digested, then the question has to be asked – did the Cape Clear stone now in the Cork Public Museum originate at this site? It was found a good half mile away, in a different townland – but this might suggest that an earlier antiquarian (or interested observer) discovered it on the hill and had it moved to Croha West for safekeeping, display, or even because it was thought it might have some value. No-one on the island seems to have any knowledge of this distant event. As O’Kelly says – it’s disappointing that there is no ‘story’: one might almost expect a tale of the person moving one of the ‘old stones’ having met with an unfortunate fate because of interference with the domain of The Other Crowd…

Top: looking towards the summit of Quarantine Hill – there is no clear path up there, and the traveller can be waylaid by gorse and brambles… Below: the prehistoric site – we are probably looking at the orthostats of a passage, which has a summer solstice orientation, and a kerbstone. On the right is a modern cairn while to the left in the background is the remains of one of the turbine towers

There is, surely, a strong likelihood that the Cape Clear Inscribed Stone did originate in the hilltop passage tomb, in which case we have completed the tale of its travels, up to the present day. The tomb is in ruins, although enough remains to show its shape and probable orientation. Paddy O’Leary tells the story of his investigations with Lee Snodgrass in an article for Mizen Journal, Volume 2, 1994:

…We were convinced that it was a passage tomb and that it was orientated on the rising sun of the summer solstice… We planned a two night vigil for June 1993 and were buoyed up by a good weather forecast. Saturday afternoon was sunny and we transported our equipment direct to the top of Quarantine Hill from the boat. We set up our cameras and, taking advantage of the sunny weather, took photographs, especially during the late evening, when there was a lovely sky. On Sunday morning June 20th we rose shortly after 4am to prepare for dawn. It was very cold but the sky was clear. A dull grey cloud began to show to the northeast, we set our cameras and waited for the sun. Shortly after 5am it peeped above the horizon, nestling in the gap between Carrigfada and the hill to its north… Gradually it rose in a 40 degree angle, flooding the sky with first light and mirroring its golden red orb in the brightening sea… A perfect sunrise perfectly recorded. The warmth was now penetrating almost numb fingers and feet. The line of the orientation was exactly as expected, directly along the supposed line of the passage, into the centre of the chamber… The most southerly point of Ireland had its passage tomb, with a summer solstice sunrise orientation; a nice counterpoint to the Newgrange winter solstice sunrise…

Quarantine Hill, Killickaforavane townland, Cape Clear. The view looking east – towards the summer solstice sunrise – from the prehistoric site on the summit

If the inscribed stone was, indeed, incorporated into the Cape Clear passage tomb, where might it have been placed? There are parallels in its design with some of the lintel stones at Fourknocks, but also I am drawn to similarities with stone L19 from Claire O’Kelly’s Corpus of decorated stones included in Michael J O’Kelly’s Newgrange – Archaeology, Art and Legend (Thames + Hudson, London 1982). This one is a standing stone – perhaps our well travelled stone was standing also.

Iconic passage tomb in Meath, Ireland – one of the greatest monuments to the Neolithic people in the world: the top picture shows the east face of the great mound as reconstructed by Michael O’Kelly using the white quartz stones which were revealed during the excavations (Finola took part in these digs!); the lower picture shows the entrance stone to Newgrange – the Cape Clear inscribed stone must be related to this type of prehistoric art, although situated a very long way away…

Here’s a suggestion – probably considered heretical in some quarters: why don’t we complete the travels of the Cape Clear Inscribed Stone by taking it out of the Cork Public Museum and (with some suitable ceremony) transporting it back across the sea to Cape Clear and setting it back up there for all time? For me, museums – while obviously providing safe keeping – sometimes lack the reality of true context… Alright then, if that is considered as inconceivable an idea as I suspect it would be, let’s make a very good replica and send it up to the top of Quarantine Hill. At the same time we could re-establish a pathway to attract people up there: our own pilgrimage to this very special site involved making heavy way through gorse and brambles.

Below: Newgrange Stone L19 from Claire O’Kelly’s Corpus of decorated stones included in Michael J O’Kelly’s 1982 book on Newgrange

With acknowledgements and thanks to those quoted above and the following sources, which have enabled me to pull together the story of this site: Paddy O’Leary and Lee Snodgrass (Mizen Journal Vol 2 1994 and personal communication), Michael J O’Kelly (Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Vol 54 1949), Chuck Kruger (Skibbereen and District Historical Society Journal Vol 6 2010)