This is a first – a ‘live’ blog post! I’m writing it inside an art installation running as part of the excellent Skibbereen Arts Festival. The installation is The Souvenir Shop, and it’s a huge hit with visitors. The project is conceived by Belfast artist Rita Duffy and curated by Helen Carey, and is a very unusual perspective on the 1916 Rising commemorations.

The Souvenir Shop was first shown in Dublin earlier this year – here is a review from the Irish Times – and it’s now in the perfect setting here in West Cork: O’Neill’s old sweetshop on Townshend Street in Skibbereen. The premises has been empty for years and stepping inside it today is stepping into the past: a shop unchanged over generations.

The atmospheric and nostalgic interior of O’Neill’s shop brought back to life by Rita Duffy (above): it displays and sells ‘souvenirs’ of the 1916 Rising and the events around it. It’s a piece of art which includes and embraces its customers and the ‘invigilators’ who, today, are Roaringwater Journal creators Finola and Robert

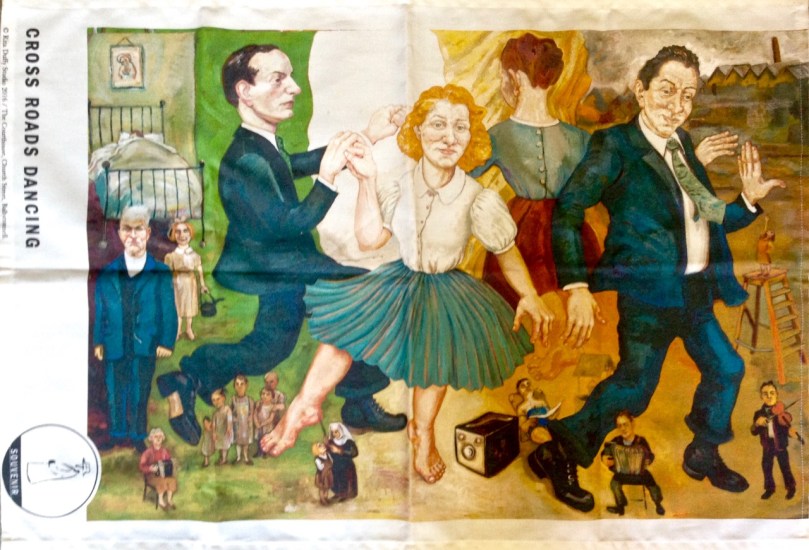

Finola and I are on our second stint behind the counter: we are the shopkeepers! We try to keep order as customers crowd in to look at the wares in display, all of which are designed by Rita. We met her in the shop on the first day of the exhibition and she explained that, during the Rising on Easter Monday 1916, many shops in Dublin were looted: the first was Noblett’s Sweet Shop on Sackville Street, and another was Tom Clarke’s tobacconist shop on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street). She has re-made or re-imagined these shops for the installation, and filled the empty shelves of O’Neill’s with an incredible array of objects – most of which are for sale.

Dublin’s 1916 Easter Rising was accompanied by widespread looting of shops: Noblett’s Confectionery (top left – Dublin City Photographic Collection) and Clarke’s Tobacconist (bottom – National Library of Ireland) were among the first casualties. Tom Clarke himself (above right) was the first to sign the Proclamation of Independence, and was a driving force behind the rebellion

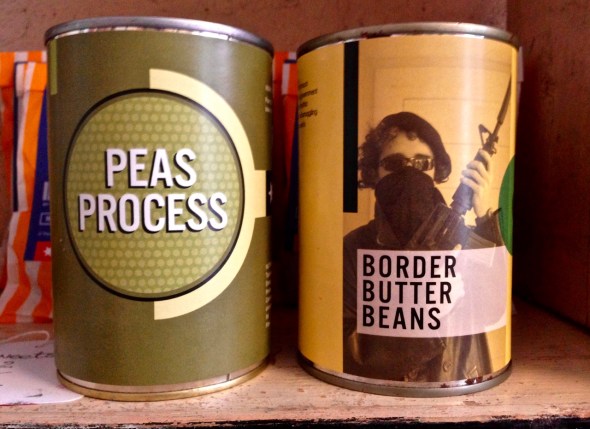

Rita Duffy’s subversive commentary on the Rising and the events that led from that time towards the present uneasy ‘peace process’ includes re-interpretations of everyday items that we would expect to see on the shelves of our local shops – soap, boot polish, tinned foods, tea, sweets, packets of seeds… It all looks very normal when you walk in – with a period flavour. We are finding that many of the customers today have fond memories of O’Neill’s sweet shop recalled from their childhoods and are delighted to come in and see it back in business: we can’t resist nostalgia. The initial impression is exactly that – a rosy-hued look back on our remembered past. Then we all start looking more closely at what is on the shelves and we are jolted out of our reveries…

Just a few of the items on sale today in The Souvenir Shop. Look carefully – ‘No Surrender stain remover’ shows James Connolly’s blood stained shirt worn during the Easter Rising; ‘His Majesties Ltd comforting diasporic foot soak for the wanderer who seeks a better footing’; ‘On The Run embrocation for the sore and twisted limbs of the dissident thinker (apply before sleep in a safe house)’; ‘Put my grandfather back together’ bandages; ‘Towards a New Republic Clear the Air vapour candle’…

It makes you laugh, initially – and then you have to think what you are laughing about. Balaclavas, in powder blue and pink with orange trim, for example. Black and Tan boot polish…? There’s a whole lot more to The Souvenir Shop. Rita Duffy has engaged the services of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association in Cavan (her studio is in Ballyconnell) to make Free State Jam and to knit – the balaclavas for example – but also some wonderfully bizarre religious iconography: did you ever see a knitted Pietá before?

Unexpected knitting courtesy of the Cavan Irish Countrywomen’s Association

Rita has also produced tea towels, t-shirts, and some embroidered place-mats carrying rather uncomfortable messages to entertain your dinner guests with. There are also ceramics: teapots, dishes and glassware. It’s such an eclectic range of goods on offer in this shop. That’s why the crowds come in and spend what seems like hours browsing the shelves that once held jars of sweets and packets of tea. There are sweets and tea here today – children are delighted to be given some free samples – but they probably don’t understand the hidden messages on the colourful packaging.

Most stark, perhaps, are the seeds: Seeds of the Revolution: two packets for 5 Euros. The messages here are fairly easy to read, although harder to digest. They really are seeds in those packets, but you’ll have to plant them to find out what comes up, perhaps something else that has a subversive implication: I’ll tell you what mine are next spring!

There’s so much in The Souvenir Shop that I haven’t included in this little review – and I’m far too busy trying to fend off the demands of the customers while I’m writing this. If only they would get into an orderly queue – it’s like some sort of insurrection in here… But we’ll cope – and encourage you to come and see this piece of artwork while it’s still on (it finishes on Monday 1st August at 5pm). Step inside and you become part of the exhibit – just like we are right now. You’ll enjoy it, perhaps more than you should. It will certainly leave you thinking.

The Souvenir Shop (…nothing is as it seems…) is one of the major projects commissioned by the Arts Council of Ireland’s Art 1916-2016, marking the centenary of the 1916 Rebellion – with the support of Cavan Arts Office and the Irish Countrywomen’s Association. It runs through the Skibbereen Arts Festival between July 22nd and August 1st in O’Neill’s old sweetshop on Townshend Street