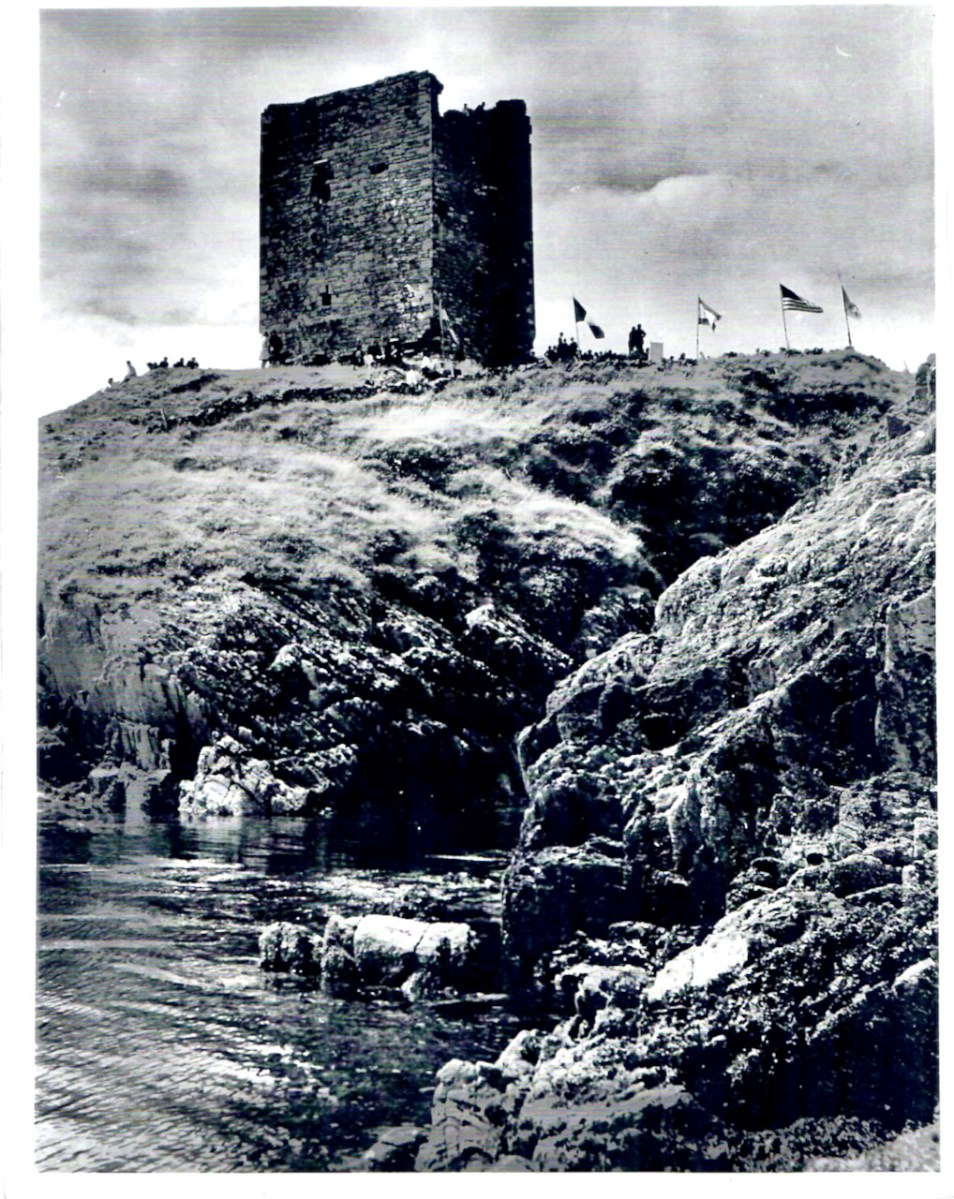

We’ve been wanting to visit this site for ages and the opportunity came this week, thanks to the kindness of Diarmuid Kingston and Tim Feen of Dúchas/the Clonakilty Historical Society, and the landowner, Jim Molony. As the Heritage Council said when they posted the photo below on their Twitter account – it’s a bit of a stunner!

Partly, this outing was to kick off a project I have in mind to follow in the footsteps, 100 years later, of Thomas J Westropp, the antiquarian who did so much to modernise Irish Archaeology and whose special interest was forts and fortified headlands. I already wrote about one of the promontory forts that he documented and we visited last year – Gouladoo, on the Sheep’s Head. I suppose that was In the Footsteps of Westropp 1, Part 1, and this is Part 2.

Let’s review what a promontory fort is. In 2004 Liam Downey laid out the thinking on this type of monument for the Archaeology Ireland/Wordwell Heritage Guide series. He called them ‘enigmatic.’ They are headlands fortified at the narrowest part, or neck, by earth or stone banks, ditches or walls and they vary considerably in the size of the enclosed area and the length of the fortifications. The sea and the cliffs all around the enclosure provide another level of defence, often seemingly impregnable.

This type of fortification may have been built as early as the Bronze Age, although most are believed to date to the Iron Age (from 500BC) or the Early Medieval Period (from 450AD), but many were obviously also occupied in the medieval period, when additional defences were added, as at Dunworley.

Why were they built? Downey says this:

Their overtly defensive character and exposed locations, allied to the admittedly scarce excavation evidence, suggest that they might have been built as temporary refuges for use in times of grave danger. On the other hand, assuming that defence was the purpose, the cliff-top location suggests a fight to the death rather than a safe refuge. Assuming that human nature does not change radically from one era to another, one potential explanation for the location is prestige. Several promontory forts are built on a large scale and some are very impressive in appearance, especially those with closely spaced walls or banks. These may have been status sites, visible from a distance and designed to dominate the adjacent countryside. The spectacular locations, unspoiled sea views, occasional associations with royalty, pagan deities or St Patrick, and even the element dún combine to suggest that the social role of these monuments in ancient times may have been quite complex.

In the light of all this, let’s take a look at Dunworley. It’s unusual, in that the narrow neck of the promontory has had an additional feature built on it, in the shape of a small tower house – a gate house, in fact.

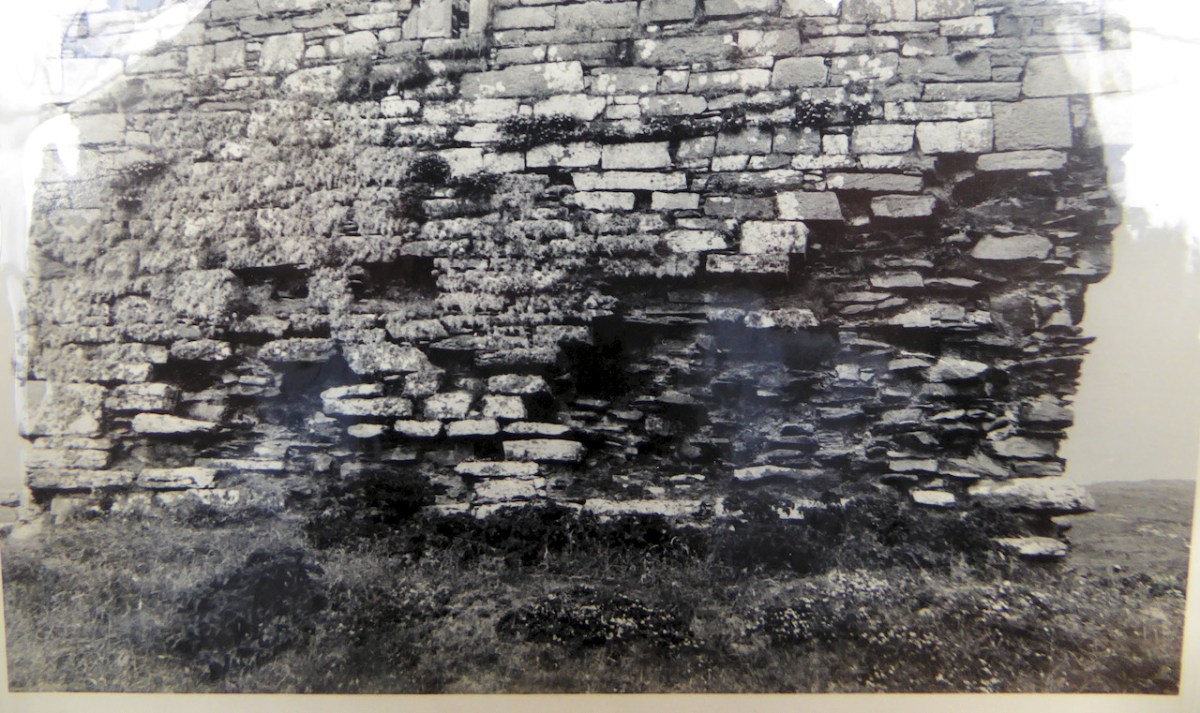

The features of this small tower (our guides called it a wee castle) are pretty typical of fifteenth century tower houses in West Cork (except on a smaller scale), with a base batter (lowest level splayed outwards), rubble construction, and inside one ope with a splayed embrasure (below). The two doors, back and front, are simple affairs and there is no sign of bar holes, eye or spud stones for the doors.

One of the more curious features, noted by Westropp, is that there appears to have been two floors, as evidenced by the corbels upon which the floor joists would have rested (below). However, the corbels are less than a metre apart, so it is hard to imagine how that space would have been used.

The internal vault, which would have separated the lower floors from the topmost floor and the wallwalk, is not a continuous vault but two arches which are covered by large slatey slabs. Although not as common as the continuous vault (see Dunmanus for an example of this), I have seen this type of vaulting in other West Cork towers – at Dunlough, for example, and less obviously at Dun an Óir on Cape Clear and at Rossbrin – all 15th century tower houses of the West Cork Irish families of O’Mahony and O’Driscoll.

Westropp, in his 1916 paper Fortified Headlands and Castles on the South Coast of Munster. Part I. From Sherkin to Youghal, Co. Cork, gives a complicated genealogy for the fort. He says it was destroyed by Fineen McCarthy after the Battle of Callan in 1260 – and this would imply that whatever original fortification was here, it was built by an Anglo-Norman family, since it was the anglo-Norman castles that Fineen destroyed. It may then have been taken over by the O’Cowhigs, but was definitely held by a branch of the Barrys by 1573. It passed to the Travers, the Hamiltons and back to the Travers. Jim Moloney, the present owner, told me that it has been in his family since his grandfather bought it.

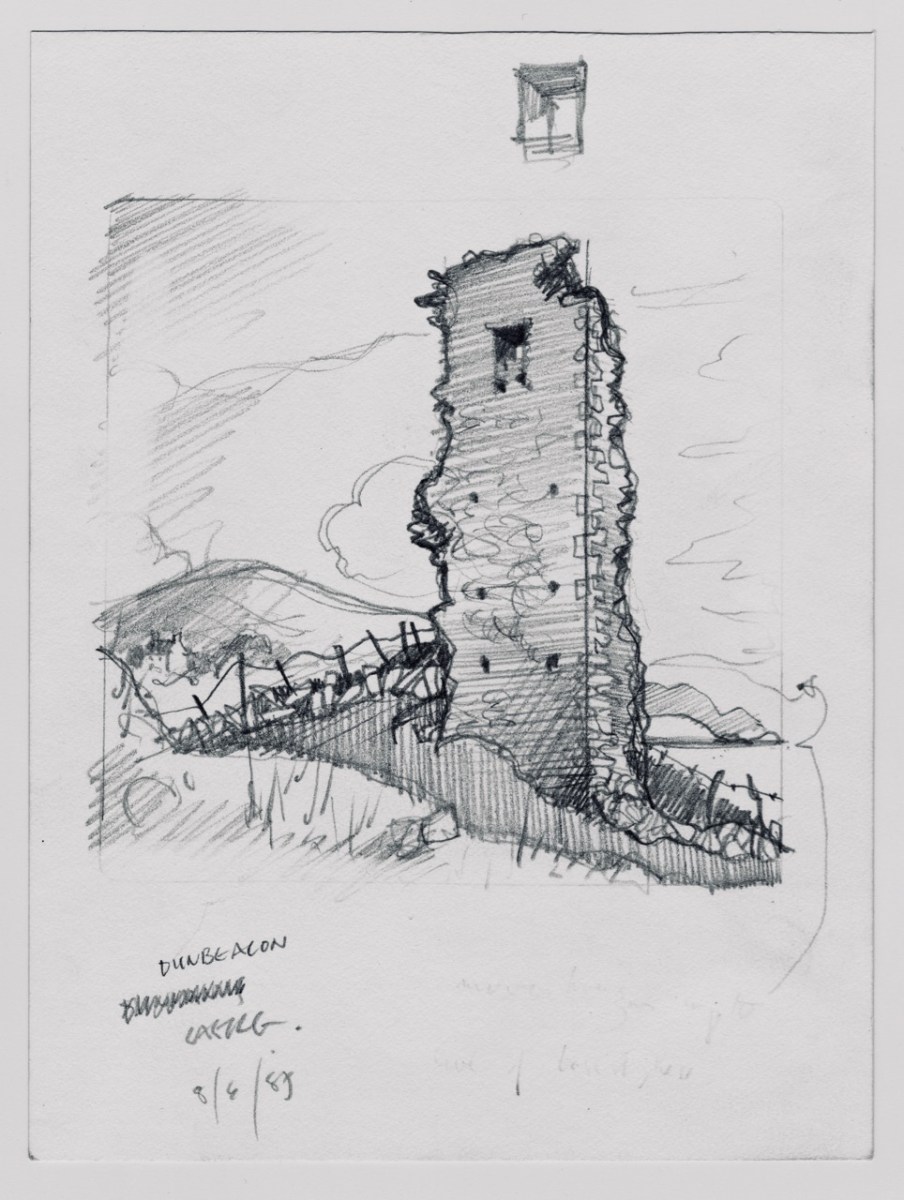

Westropp, in his usual thorough fashion, provides a drawing of the small tower, both its position at the neck of the promontory, and a plan of the building itself – the top left and top centre plans below.

Some accounts mention a house on the promontory, but Westropp saw no sign of one. He did, however, note:

The day of my visit the headland was covered with cattle ; and it was interesting to see them, when called out to water, going in single file, without delay or hustling, through the little doorways, the outer 3 feet 1 inch wide, by 5 feet high ; the inner 2 feet 10 inches wide, and 5 feet 9 inches high. This shows how easily cattle might be brought through the small doors (but usually wider and higher than this gateway) in the dry-stone ring-forts.

This is particularly interesting because the land is considered unsuitable for livestock now, because of the difficulty of getting them on and off the promontory and because there is no source of water on it. In any case, it has been declared an Area of Special Conservation, since the cliffs are home to nesting choughs – a very suitable designation for such an epic place.

The day of our visit was a stormy one – Amanda was actually blown off her feet at one point. It was easy to see how such a place could be defended in times of attack, and act as a refuge. The whole area had such a wild, remote and romantic air that we truly felt privileged to be able to visit it, and to step back in time to imagine it in its heyday.

You can see us below, bracing against the wind. Many thanks to Diarmuid, Tim and Jim for facilitating our visit and answering all our questions.