It’s October: autumn light is playing on the skies and seas as we set out to cross the Sheep’s Head peninsula on a path which is new to us. The path traverses the backbone of this peninsula – a ridge which is virtually continuous from east to west – and runs from Rooska, a settlement beside Bantry Bay on the Northside, heading south for Coomkeen and then Durrus. Before we take to the hills, however, we need to prepare ourselves with some sublime scenery en-route, a little excursion into vernacular architecture, and an encounter with local expertise.

From upper – a Sheep’s Head pastoral, the view over Glanlough towards distant Beara; a perfect composition in tin and stone; a niche for offerings? Looking to the ridge – and The Big Gap – in the distance; Joe O’Driscoll with his architectural egg-box. Unfortunately the hens are not laying at the moment!

We are heading to the start of our climb and find a busy settlement, historically once a mining centre and now home to a major award winning seafood producer, bravely weathering the Covid storms. It’s worth a look at their colourful website! You might not expect to see such a venture on the wild and remote Sheep’s Head Northside, but it’s a great boost to a fragile local economy. We wish them well in surviving the Covid19 crisis. Parking up at Rooska, we get first sight of the zig-zagging route that will take us over towards Durrus, passing through The Big Gap at the summit of the hill.

Upper – looking north across Bantry Bay from the path; middle – from the south, the path descends through The Big Gap; lower – the path can be seen on the right cutting through the hills: the highest point is 200m above sea level

I tried in vain to find a name for the way we followed. I would like to have called this post The Mass Path, which is given to it on a modern guide, and it does seem probable to us that one purpose of the trackway would have been to take Northside dwellers over to the old Catholic church at Chapel Rock in Durrus, a distance of 7 kilometres (or four and a half miles in older times). There and back would have been a taxing walk for a Sunday morning on an empty stomach (you have to fast from midnight before taking communion)! However, we were told locally that our intended way will lead us through The Big Gap, hence my title.

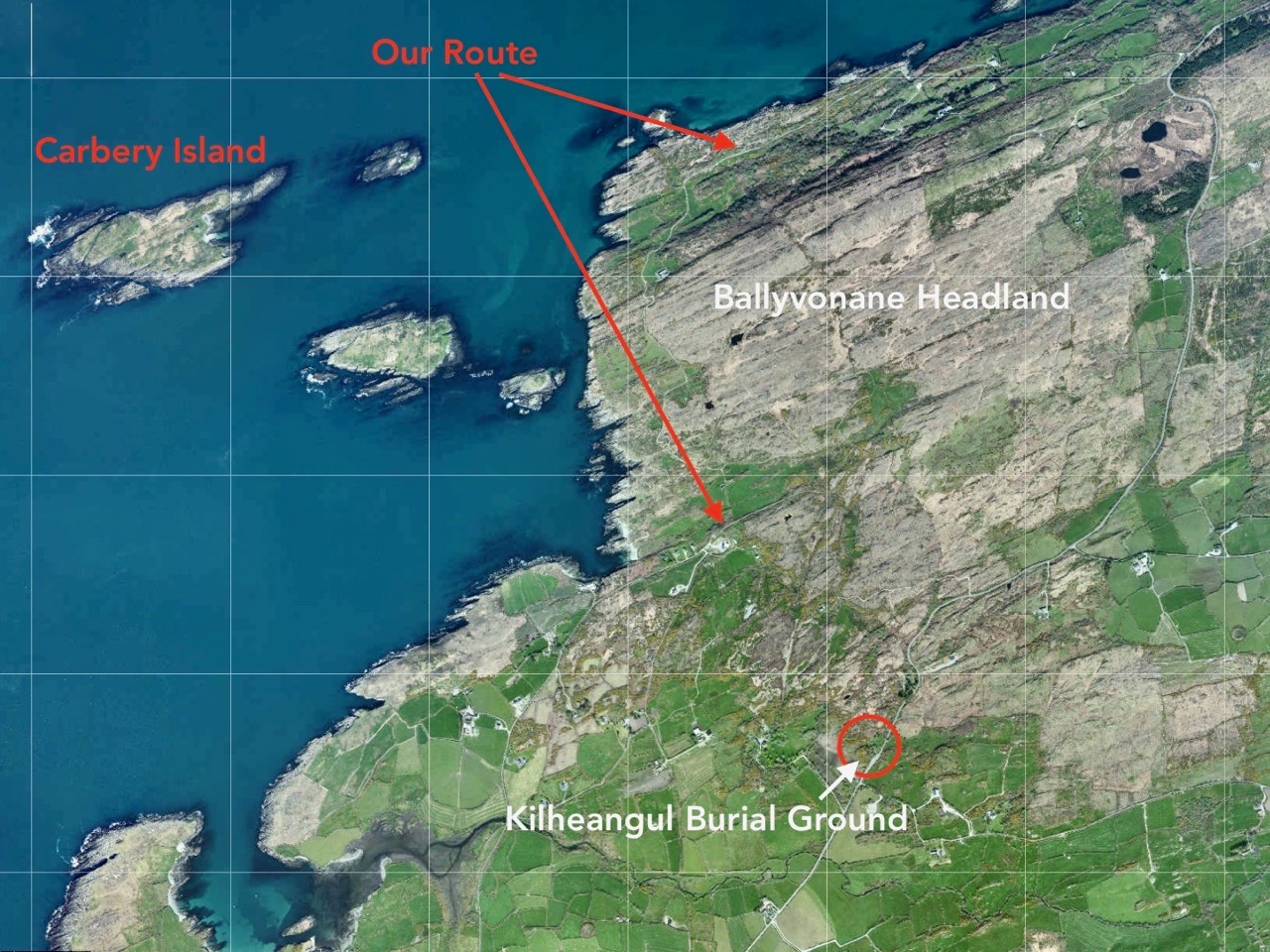

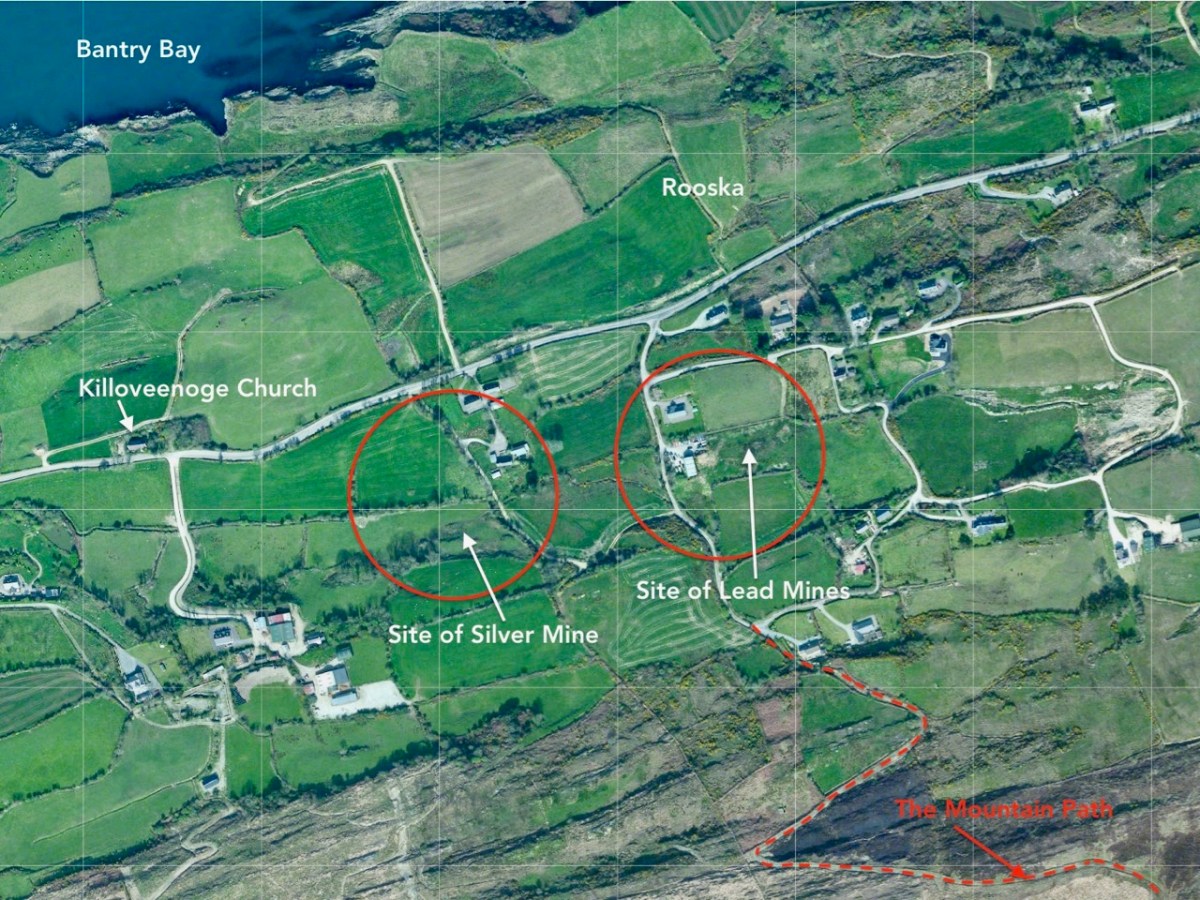

This view over the Northside area of Rooska, above, shows several features and the beginning of the path over the mountain heading south. Notable is Killoveenoge Church, known as a ‘Chapel of Ease’ and said to have been built in the 1860s specifically for the English and Cornish miners who were working in the nearby silver and lead mines at the time. There are scant remains of these mines now, and the Church of Ireland building was closed in 1988 and converted to a studio.

Looking down on Killoveenoge Church from The Big Gap path, with Bantry Bay beyond

The townland name Killoveenoge translates as Church of the Young Women and the only explanation of this I could find suggests that the site was anciently a priory, sacked by the Vikings in 890AD. It is also said that some ruins of this are visible, but we failed to find them – nor any factual historic records. The Schedule of Monuments notes a circular burial ground in the west of the townland with early grave markers, but nothing more. Clearly folk memory transcends recorded history, and that is one of the attractions of Ireland – to us, at least.

Upper – The Sheep’s Head Way trails have a strict code, which benefits all users; middle – the ruins of a cottage almost lost in the furze. The mining records mention a ‘miner’s cottage’ still being visible: could this be it? Lower – gaining height as the path gets steeper: that’s Whiddy Island in the distance

The wider aerial view shows the full length of the old trackway as it crosses the mountain through The Big Gap. Just past the summit when heading south is another landmark, also holding a folk memory. Lough Na Fuilla translates as ‘Lake of the Blood’:

A reed-filled lake suddenly appears; so many different greens, so far from anywhere and the gentle murmuring of the reeds all combine to make a rather unsettling atmosphere . . . Maybe it’s knowing the name of the lough, Loch Na Fuilla, lough of the blood, that plays tricks on the mind. There is a story attached, of course. One extremely hot summer the cattle came down from the mountain in search of water. The lough was empty. Maddened with disappointment and thirst the cattle went berserk and attacked each other and many were killed.

Walking the Sheep’s Head Way – Amanda and peter Clarke – Wildways Press 2015

Lough Na Fuilla, and a nearby tarn on the east side of the trackway. The autumn colours are sublime

Neither the Lake of the Blood nor the nearby tarn are shown on the early OS maps. The few remaining mining records, however, mention that there was some prospecting activity up on the ridge: could this have relevance? And is this another reason for the existence of this path? We are impressed with the views from The Big Gap both north and south. We temporarily divert on to a stony sheep path to get even higher, and to find the best panoramas. From the ridge we also record the contrasting light and shadow effects from a constantly changing sky.

We pause to wonder whether a large rounded outcrop is the Eagle’s Rest which is mentioned by local historian Willie Dwyer, of Rooska:

The gap going through the mountain there, by Loch na Fuilla, the locals always called it, that’s the old people who are dead and gone now, used to call it “Barna Mhór” which means “The Big Gap”, and on the right-hand side (the north-west corner) before you come to the extreme top of the track, there’s a round bald rock which was known as “the Eagle’s Rest”. I don’t know how long the eagles have been gone out of this part of the country, but it must have been a long time ago. This is a tradition now, it has been passed down as tradition, how true or false it is, I can’t prove to you.

Willie Dwyer, Quoted by TOM WHITTY in ‘A guide to the Sheep’s Head way’ 2003

From The Big Gap it’s downhill all the way! As we walk south it’s the Mizen which is always on the horizon, across the waters of Dunmanus Bay.

As we approach the southern end of the trackway crossing the mountain, we look back up towards Barna Mhór – The Big Gap. It has been a most rewarding adventure for us, and one which we intend to repeat at other times of the year so that we can capture the effects of the changing seasons.