Originally posted in 2015. Re-posted now, 8 years later with an update at the end.

Some posts are hard to write. In the case of this one, there are such complex emotions – sadness and anger being the dominant two, but overlaid with pride and gratitude. I will explain.

On June 23rd, 1985 – 38 years ago this week, but 30 years ago when this post was originally written – a bomb on board Air India Flight 182 exploded when the plane was just off the coast of West Cork. Everyone on board, 329 people, were killed. One in every 4 victims was a child. Eighty percent were Canadians.

The bomb was the work of Sikh extremists, operating out of Vancouver. A botched investigation, jurisdictional disputes, and massive incompetence at many levels has meant that no perpetrator of this heinous crime has ever been convicted for it – a travesty that is a dark stain on Canada’s judicial system and that has left the families of the victims with no sense of justice to this day.

Members of the victims’ families began arriving immediately after the bombing and, deeply affected by their plight and by their own traumatic involvement in the the recovery operation, the people of West Cork opened their hearts and homes to them. Ahakista residents took on the task of petitioning governments for a memorial garden and of arranging a yearly commemoration service. The memorial is beautiful and perfectly maintained year round. Beginning in 1986 the service has been held every year without fail and family members who come are welcomed, supported and fed, in the Irish way. Many friendship have been forged over the years.

In contrast, it took the Canadian Government a long time to acknowledge that this terrorist attack, in the words of Prime Minister Harper’s official apology ‘…was not an act of foreign violence. This atrocity was conceived in Canada, executed in Canada, by Canadian citizens, and its victims were themselves mostly citizens of Canada.’ This speech was made in 2010. The first Canadian memorial to the victims was erected in 2006 and there are now four. There are no memorials in India.

Because 2015 was the 30th anniversary the ceremony was a large one, with dignitaries from Canada, India and Ireland in attendance and about twenty family members. For us, it started the night before, with a poetry reading in the West Cork Arts Centre in Skibbereen. Renée Sarojini Saklikar is a Canadian poet who lost an aunt and uncle in the disaster. She read from her book Children of Air India, and also some new pieces. Deeply influenced by the opacity of official documents, by memory and loss, her poems carried a quiet power that seeped into our souls almost without our noticing. She elicited our participation in one poem – a piece made up entirely of acronyms – and she spoke to us about the process of writing poetry from trauma and invited our stories and comments. It was a deeply emotive experience – a good preparation for the following day’s ceremony of remembrance.

The ceremony timing mirrors the events of the original June morning when the bomb exploded in the plane, with a minute’s silence at 8:12AM, broken by chanting by family members. The Irish Navy were on hand to signal the moment with a siren blast, and a Coast Guard helicopter performed a formal fly past. A choir of children of the local National School sang and there were speeches and wreath-layings. I was pleased to see Canada’s Minister for Justice, Peter McKay, in attendance as well as the Canadian Ambassador to Ireland.

Speaking to the family members brought home to me as nothing else could do the enormity of the tragedy and the still-raw emotions at the core of this event. Saroj lost her father, a teacher. “He was a proud Canadian,” she said. “He loved Canada and taught Canadian children in Newfoundland. He cared so much for his new country, but when he died, suddenly in the eyes of Canada he was no longer a Canadian but an Indian.”

Saroj (below) had sat through many days of the Vancouver trial of the accused bombers (who were eventually acquitted) and still could not get her head around the outcome when the evidence was so clear.

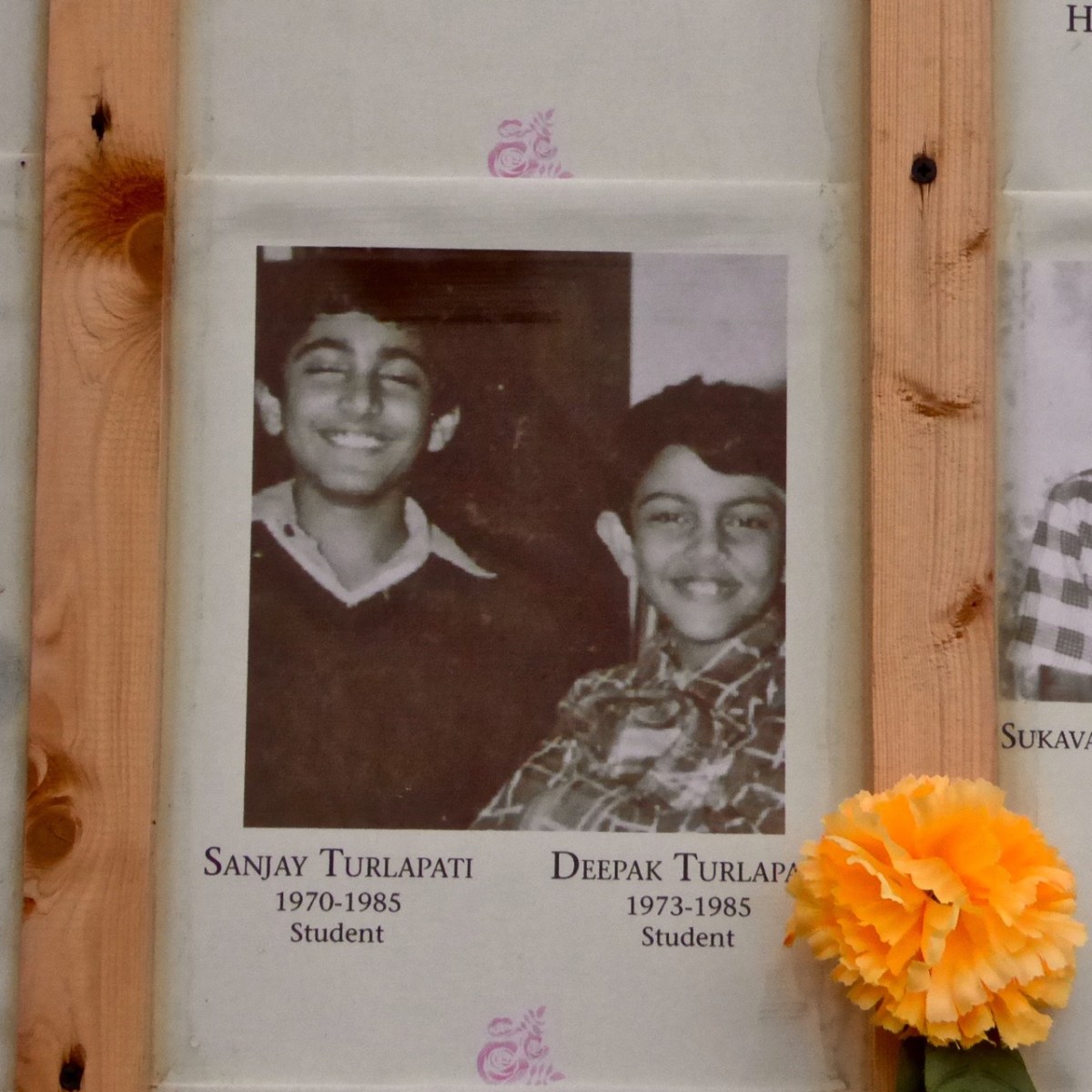

Dr. Padmini Turlapati (in the sari, below) was the spokesperson for the families. She lost her two sons. They had just finished school and were going to India for the summer to see their grandparents.

She showed me their photograph – two merry kids, laughing and carefree. Because they were visiting their grandparents they had taken with them their albums of mementoes and photographs – Padmini had to piece together a few photos from their school and friends. Sanjay’s body was recovered, but Deepak is still out there, and so she comes back every year to the place which has become a focus for her grief. In her speech she encompassed all the emotions that the families still feel – unspeakable sadness, anger and – gratitude.

Over and over speakers spoke about the warmth, the generosity and the support of the West Cork people who had been there for them in their despair when it seemed that their governments had abandoned them. Several used the same phrase. Addressing themselves to the people of Ahakista, to the fisherman and coast guard volunteers, to those who built and maintain the memorial and who organise each year’s ceremony. “You”, they said, “are a model for the world.”

Renée was there, honouring her aunt and uncle, both doctors, both contributing enormously to Canadian society.

As a Canadian who listened nightly to the reports of the Vancouver trials I can have an inkling of the unfathomable well of loss and anger that these families feel. As an Irish person who is now living in West Cork I am proud of how our neighbours and friends stepped in to support and comfort these devastated families.

Perhaps the best way to end is with one of Renée’s poems. I will try to reproduce it faithfully on the page.

In the home-house, in the basement, there is the mother — she is singing a sweet song.

It is before —

June 1984

Of her name, there are redactions.

Of her mother tongue, there is no record —

this is the life of a woman, made in India,

living in Canada.

In the home-house, in the basement, there is the mother

And she is absent, sister

Update, 2023

We visited the memorial this week, on Friday the 23rd. The ceremony had taken place, as always, in the morning and the site looked beautiful despite dismal weather. Fresh flowers had been laid, including, most poignantly, for Sanjay and Deepak.

Nothing has changed for the families. The man who was tried and acquitted in the infamously botched trial in Vancouver, Ripudaman Singh Malik, was shot dead last year in what appeared to be a targeted gangland-style killing. Although two men were charged for the murder, the trial has yet to be held. Malik had many enemies and had earned more by a recent turn-about in his support for the Indian Government, and nobody has linked his murder to the Air India Bombing. In the last few days, another prominent Canadian Sikh activist, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, has also been murdered in a similar way. It is speculated that his, and other recent deaths, are linked to the movement for a Khalistan state as a Sikh homeland.