I have long been a fan of Maura Laverty. I was delighted to receive as a Christmas present from my brother a copy of a book by her called Feasting Galore: Recipes and Food Lore from the Emerald Isle. For more on Maura Laverty, and as background to this post, it might be a good idea to go back now and read my post Kind Cooking.

Feasting Galore appears to have been a book written (or rather compiled, as it seems to have borrowed stories and recipes from her other books) especially for the American market (Emerald Isle in the title is a clue). One of those books, of course, was Full and Plenty and there’s great news, by the way for Maura fans – Mercier Press, who owns the publishing rights to Full and Plenty and currently has an abridged version available, is going to re-issue it in full later this year.* I’ll be lining up!

The forward to Feasting Galore is by Robert Briscoe, the Lord Mayor of Dublin in the 1950s and early 60s (below, with JFK on his state visit in 1963). In his remarks he comes up with the following startling claim, Her knowledge of Irish traditional cooking makes her a leader in this field, and this knowledge she has gained from a detailed study of the lives of the early Irish Saints which are our chief source of information concerning the domestic ways of the ancient Irish. Having read something of Bob Briscoe as he was universally known in Dublin, I can see his tongue firmly in his cheek here and his audience in mind. And having read the book, I see Maura laughing her way through the whole project.

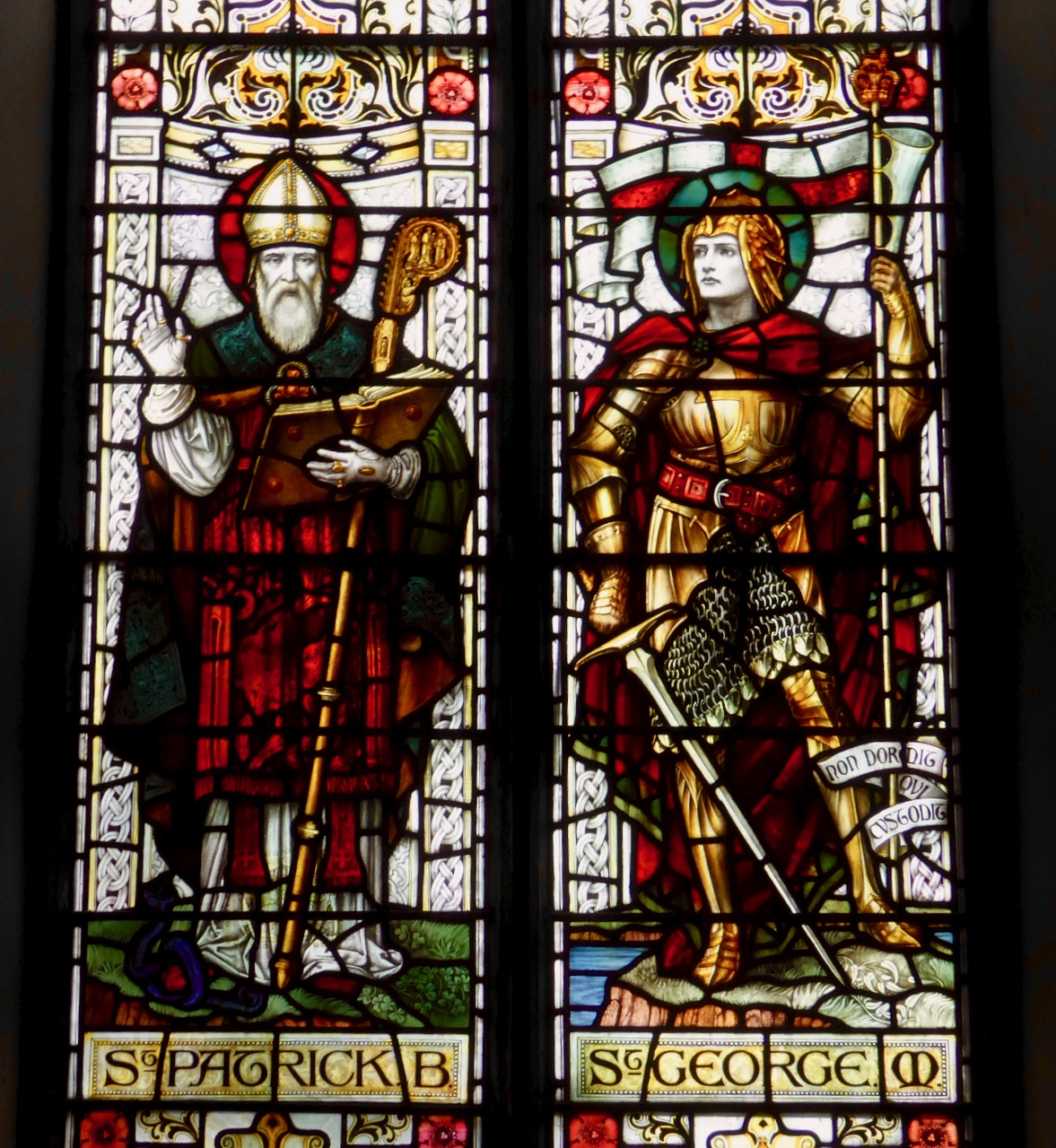

Now, as my readers know, I love a good saint. Briscoe’s reference was irresistible and sent me searching through the book for all the saintly references. I found lots of them! Before I get to the Saints though, I thought you might like a rundown on some of the traditional Irish recipes we don’t hear much about nowadays. After reading the list you might feel there are good reasons for that.

Let’s start with the vegetables. We begin with Brandon Parslied Potatoes, and move on to Slieve na mBan Carrots before reaching Cauliflower Souse. This is followed by Haggerty, Leekie Manglam, Nettle Briseach, Pease Pudding, Potato Collops, and Potato Scrapple. And of course Braised Cabbage and Colcannon make an appearance along with Dulce Champ.

I think you’d have to agree that of all of these Leekie Manglam is the one that needs to be investigated. So here is the story as given by Maura Laverty.

Leeks have always occupied a favoured place in Irish cooking – and with good reason. Their popularity dates back to the days of Saint Patrick. One day, so the story goes, a Chieftain who was being driven out of his mind by his pregnant wife’s demands for leeks (then out of season), employed the Saint’s help. Saint Patrick took a few juicy rushes, blessed them, and turned them into leeks which immediately cured the unfortunate woman’s “longing sickness“ and brought peace to her harassed husband. There and then Saint Patrick ordained that any woman suffering from the “longing sickness“ (modern doctors call it “pica“ or “morbid craving“) should be cured if she ate any member of the onion family.

So now you know! And here is the recipe.

Ingredients: One third recipe for Lardy cakes, three large leeks, four slices streaky bacon, half cup breadcrumbs, quarter cup milk, pepper and salt to taste, one egg.e

Method: parboil the leeks, drain, and cut them into very thin slices, add the diced bacon, mix in crumbs, milk, and seasoning. Divide the pastry in two. Use half to line a pie plate. Fill with the leek mixture. Brush edges with water. Cover with a lid of pastry. Press edges firmly together and flute. Brush with beaten egg and bake 30 minutes in a 425° oven.

As with other traditional Irish cookbooks (see this post about Monica Sheridan for example) every piece of an animal is used. There are recipes for Brawn, Cock of the North, Coddled Coneen, Griskins, Haslett, Pig’s Cheek, Trotters, and Tripe. There’s a bewildering variety of jams, jellies, scented jellies, marmalades and chutneys.

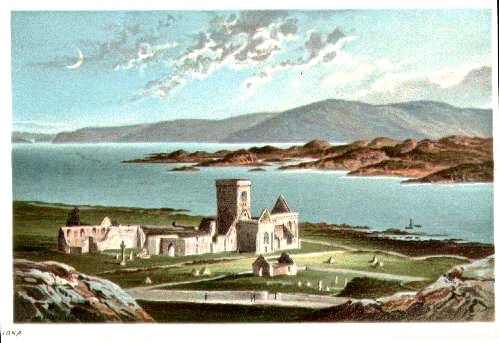

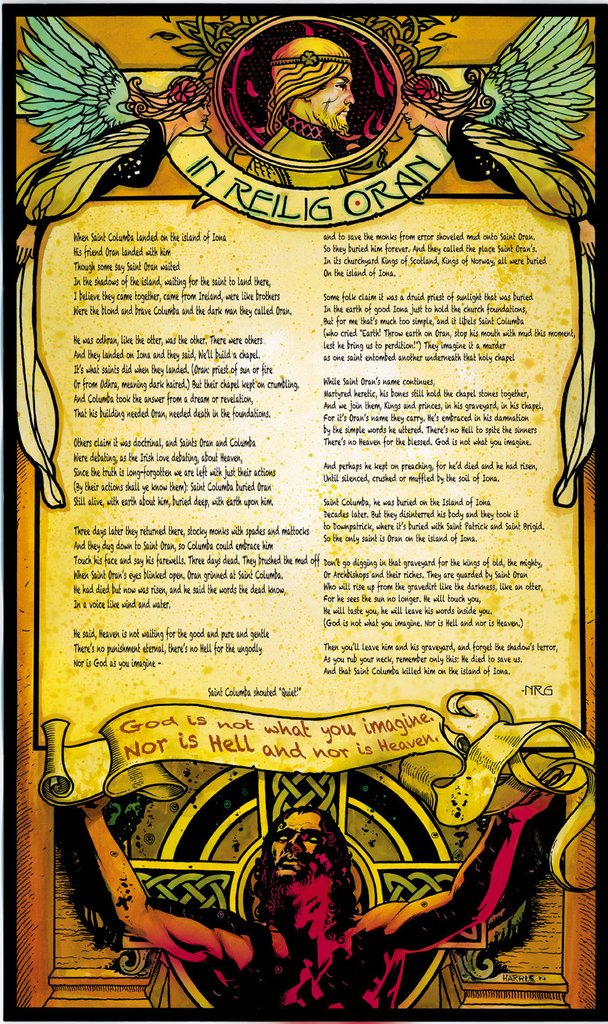

But what about the saints I hear you ask? Well, we’ve already had a taste of Saint Patrick so here’s one about Saint Columba and the recipe is for something called Brothchán Buidhe. Pronounced brohawn bwee, it means yellow broth, which is a savoury concoction of vegetable stock thickened with oatmeal and enriched with milk. It was, Laverty tells us, the favourite pottage of Saint Columba.

When Lent came around the Saint decided to mortify himself with ersatz broth, so he instructed his cook to put nothing into the broth pot except water and nettles, with a taste of salt on Sundays.

“Is nothing else to go into it, your reverence?” asked the cook in horror. “Nothing except what comes out of the potstick,” the Saint replied sternly.

This went on for two weeks. The Saint grew thinner and weaker, and the cook grew more and more worried. And then, all of a sudden, Saint Columbus started to put on weight again and the worried look left the cook’s face. The devoted lay brother had made himself a hollow potstick down which he poured milk and oatmeal. Thus he was able to preserve his master from starvation and himself from the horrible sins of disobedience and lies.

When questioned by the Saint he was able to assure him honestly that nothing went into the broth save what came out of the pot stick.

I will save you from the recipe because it looks very unappetising indeed and I can’t imagine anyone would want to make it for any reason.

The next Saint we encounter is Saint Keevóg, and he comes at the end of a version of the Children of Lir. For the complete and very sad story of the four children who were turned into swans by their wicked stepmother, you can read Robert‘s post here. Here’s Maura’s ending:

At long last the day came when they heard the mass bell of Saint Keevog. The four swans winged their way to the Saint’s little church where they were baptised. It is said that immediately after their baptism, their feathers fell from them and they reverted to human form, but incredibly aged and wrinkled.… And this story of the children of Lir explains why Swan, which was considered royal food elsewhere, is never mentioned in accounts of ancient Irish banquets. Until this day to kill a swan is an unforgivable sin in Ireland.

From poetry to pike is not such a long step, particularly when the pike is from Lake Derravara and is made into a poem of a dish in this way.

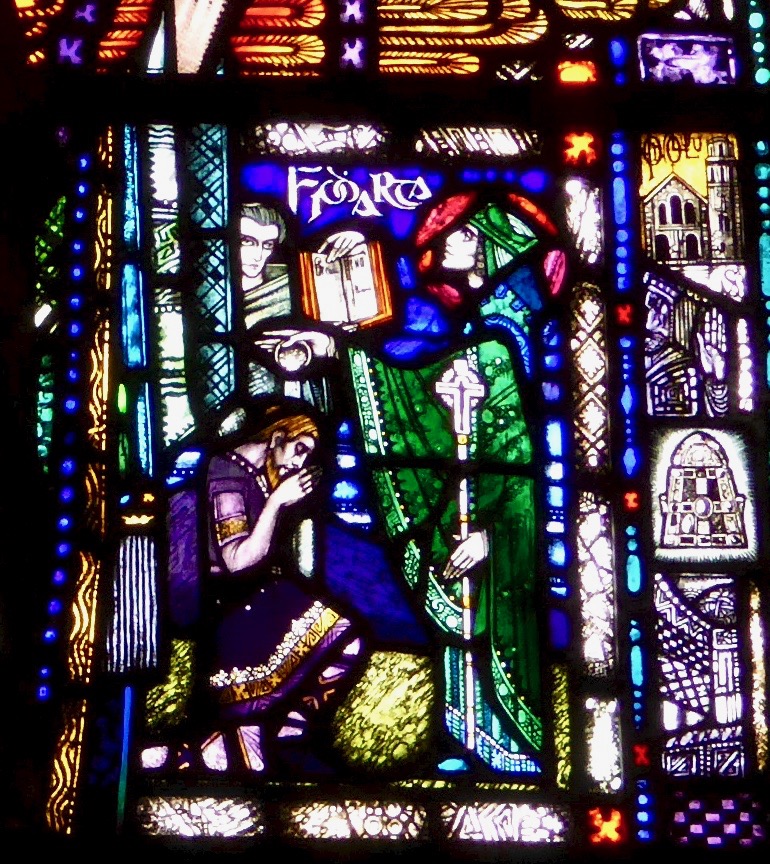

This is followed for a recipe for Pike Derravara – a bit of a stretch perhaps. Keevog is St Mochaemóg, the founder of Liathmore monastery about which we wrote here. In Robert’s version he is called Saint Kemoc, a hermit who found them, four ancient, withered people.

Did the cookie, Maura Laverty asks us, come from Ireland? Here is her answer.

The first written mention of cookies occurs in the ancient Book of Lismore.

It seems that when Saint Patrick came to Ireland he found that Ogham – the only form of writing then known here – was the closely guarded secret of the Druids. Patrick in his wisdom realised that education was a necessary preliminary to conversion from paganism, and he introduced the Roman alphabet to the people to whom he was bringing the gifts of enlightenment and salvation.

In the book of Lismore we are told that the child who grew up to be Saint Columcille found difficulty in learning the alphabet. To encourage him his mother baked A-B-C cookies with which he was rewarded as he mastered letter after letter.

It is very probable that this sweet way of coaxing children to learn became common throughout Ireland. And I think it quite likely that it was introduced to America by Saint Brendan the Navigator who discovered the New World long before Columbus set foot there.

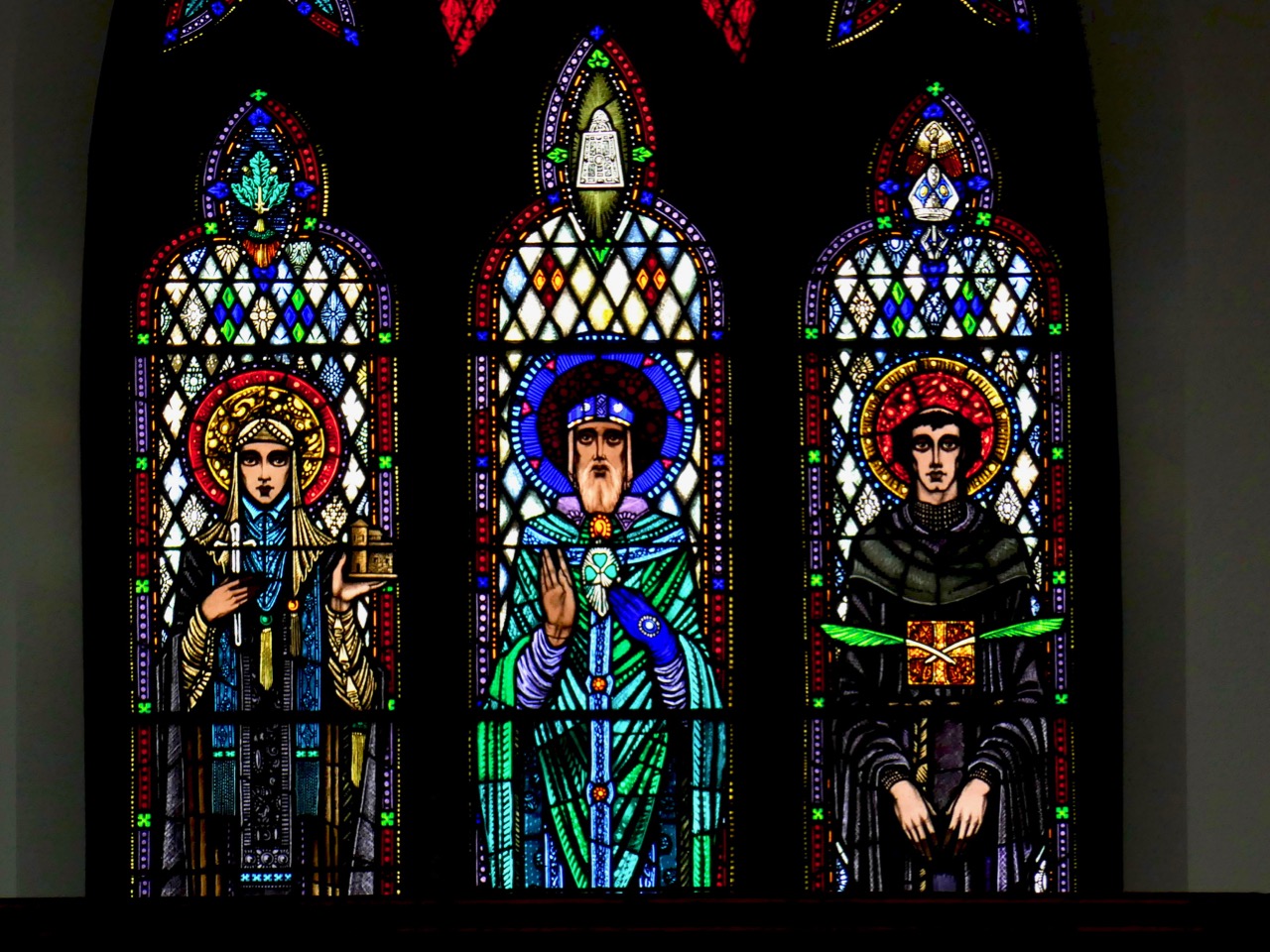

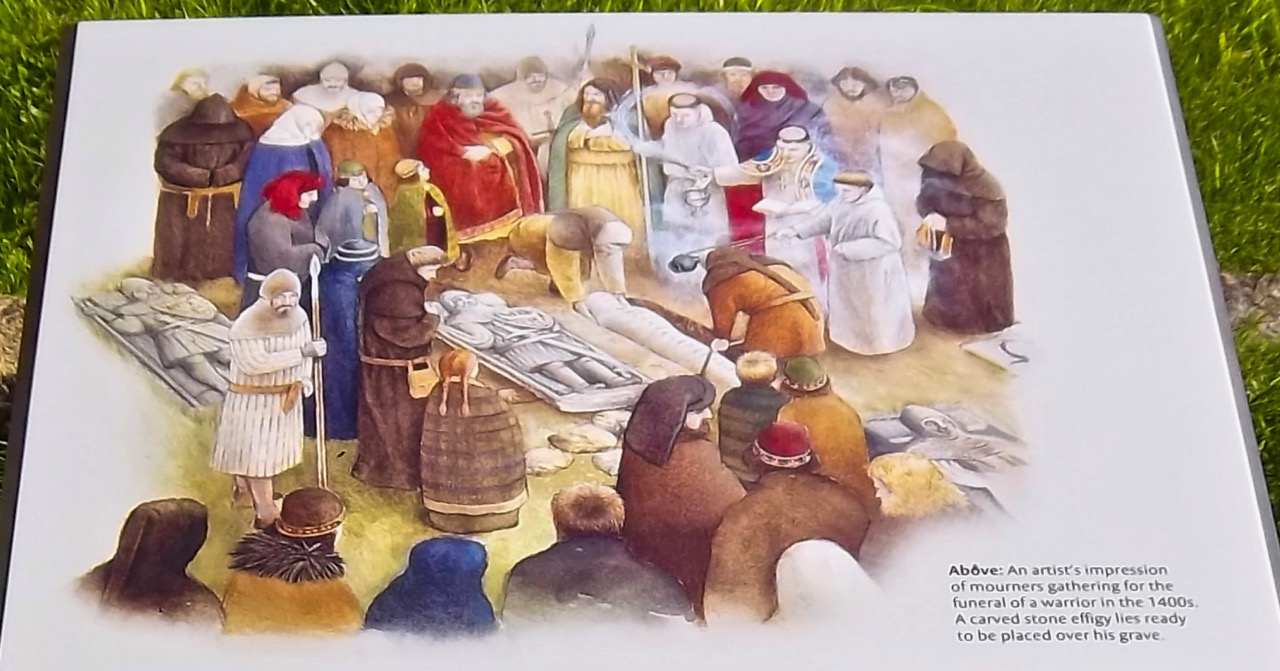

And so it goes on, over-the-top names and recipes designed to, er, feed every leprechaun-and-shamrock preconceived notion that Americans might have of the Irish. There’s a chapter on Fast-Day Feasts, and recipes for Convent Loaf and Nun’s Cake. I can only imagine the fun she had writing it. The illustrations, by Bill O’Gorman (I’ve found nothing about him – anyone?) also add to the chuckles – it’s hard to imagine a more stereotyped set of cartoons.

Each chapter is preceded by a story, mostly around the theme of food being the way to a man’s heart, and that age, girth or criminal records were no impediments to true love. I leave you with the one with which she introduces the vegetable chapter.

Now, seeing as it’s the season that’s in it, I’m off to cook up some St Brigid’s broth.

*Many thanks to Mercier Press – although they do not claim rights for Feasting Galore, I appreciate that stories and recipes in it have been taken from Full and Plenty. Feasting Galore was issued by Hippocrene Books, but is no longer in their catalogue.