We’ve just passed the Equinox – one of the two moments in the year when day and night are of equal length. This happens once in the spring and once in the autumn. This year that moment was March 20th at 9:01AM, but it can fall between the 19th and the 21st, depending on the year. The autumn equinox this year falls on Sept 22, but it can range from the 21st to the 24th.

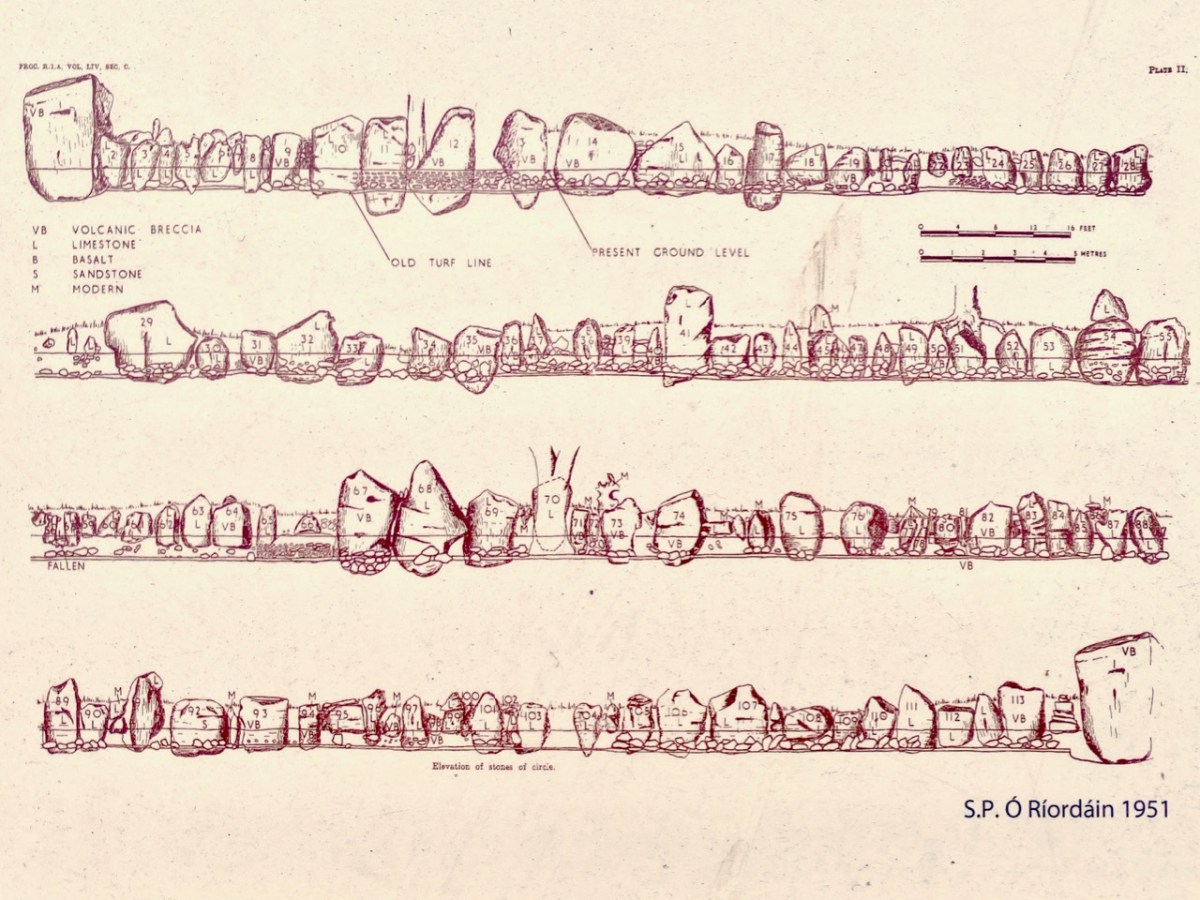

Prehistoric monuments in West Cork often have an orientation – the most famous of course is Drombeg stone circle (above in 2020). It’s a multiple stone, ‘axial’ circle, with two portal stone opposite a recumbent stone. On the winter solstice (this year on Dec 21st) the sun sets behind the recumbent, diametrically across from the portal stones (this is the ‘axis’). Attending this event is always great fun as well as an opportunity to join in a celebration that is thousands of years old.

There is a rhythm to the year provided by these four solar events – the longest day (summer solstice), the shortest day (winter solstice) and the equal-length days (equinoxes). Add to that the cross-quarter days – the points half way between the solstices and equinoxes, and we have a natural calendar of eight divisions.

The cross-quarter days, by the way, are the ones that track most closely to the great ancient Festivals in Ireland of Imbolc, Bealtaine, Luanasa and Samhain. Although nowadays these tend to be celebrated on the 1st day of February, May, August and November, in fact the dates would have varied and in 2025, the accurate dates for the cross quarter days are Feb 3, May 5, Aug 7 and Nov 7. This is important to know as various solar events happen on cross-quarter days, and if you want to see them, you have to turn up on the right day! See this post on Boyle’s Bealtaine for a good example of this – the photo above was taken on May 5, 2018.

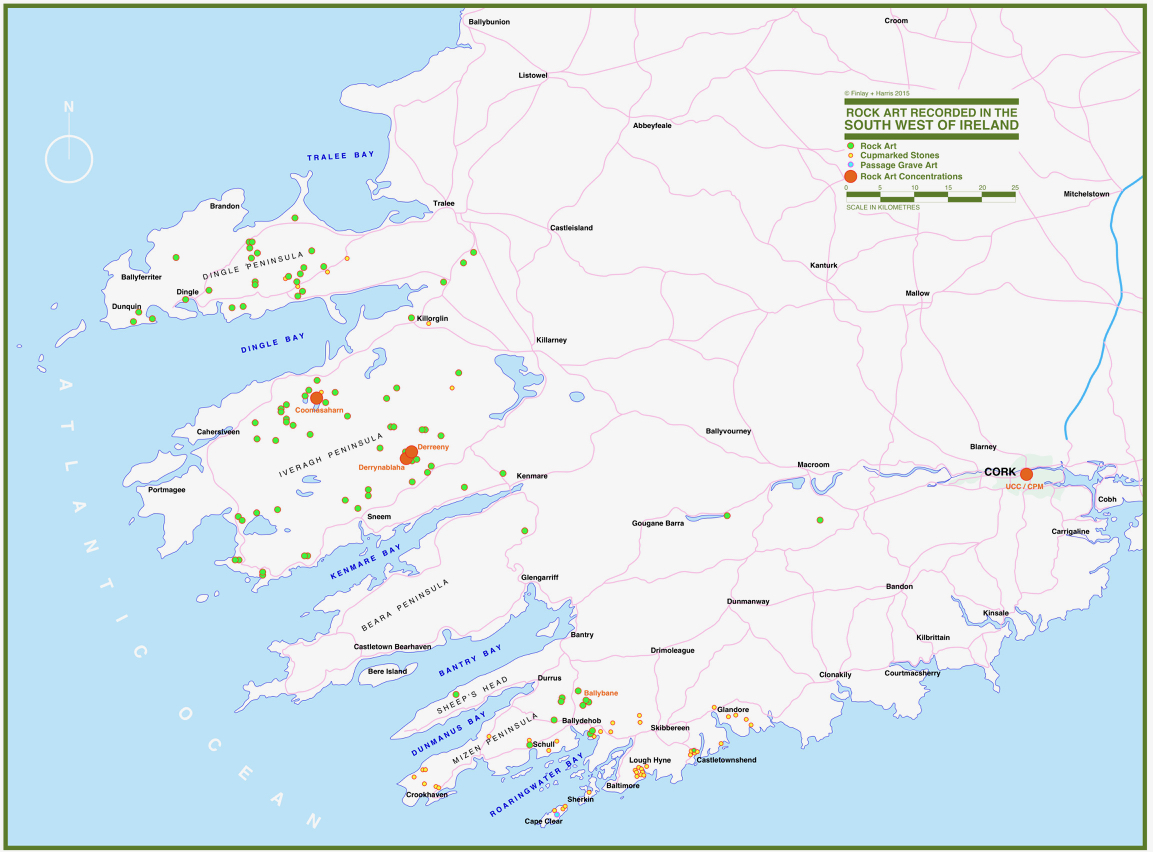

A few years ago, we met up with Ken Williams of Shadows and Stone, to photograph the equinoctial sunset at Bohonagh Stone Circle, near Rosscarbery. Ken is the undisputed master of prehistoric photography in Ireland. His website contains high-quality images of many different kinds of monuments, he supplies photographs for all the best publications, and he was our partner in the Rock Art Exhibitions we mounted in the Cork Public Museum and in Schull.

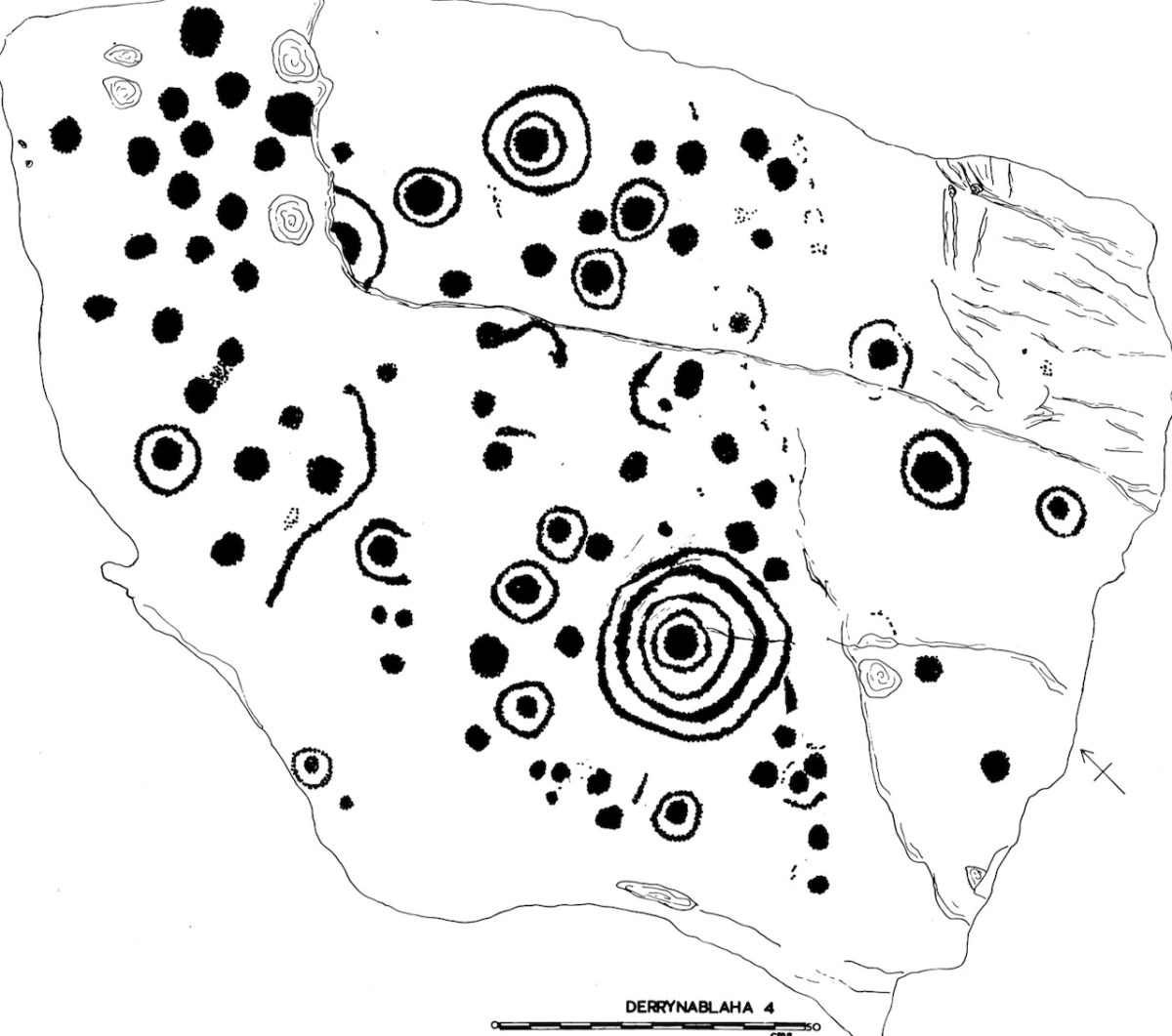

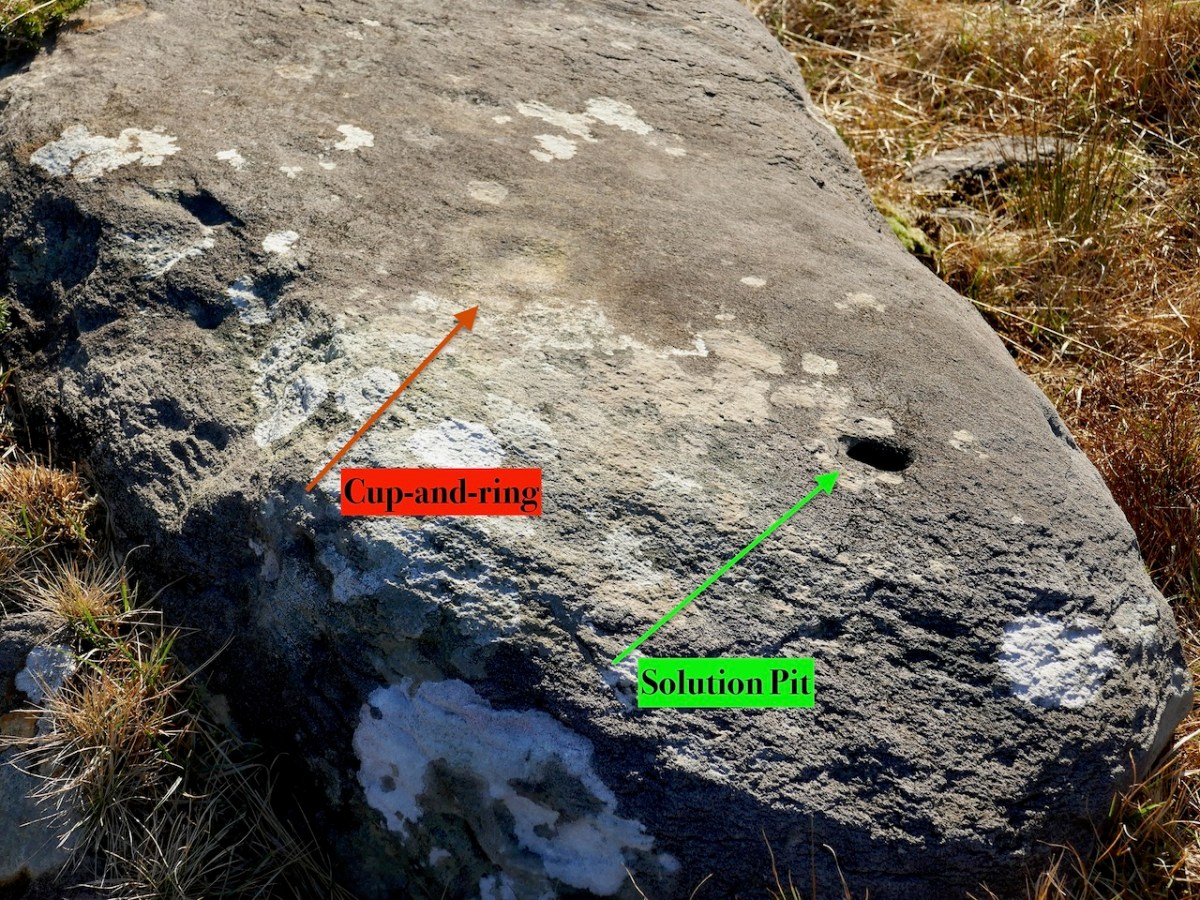

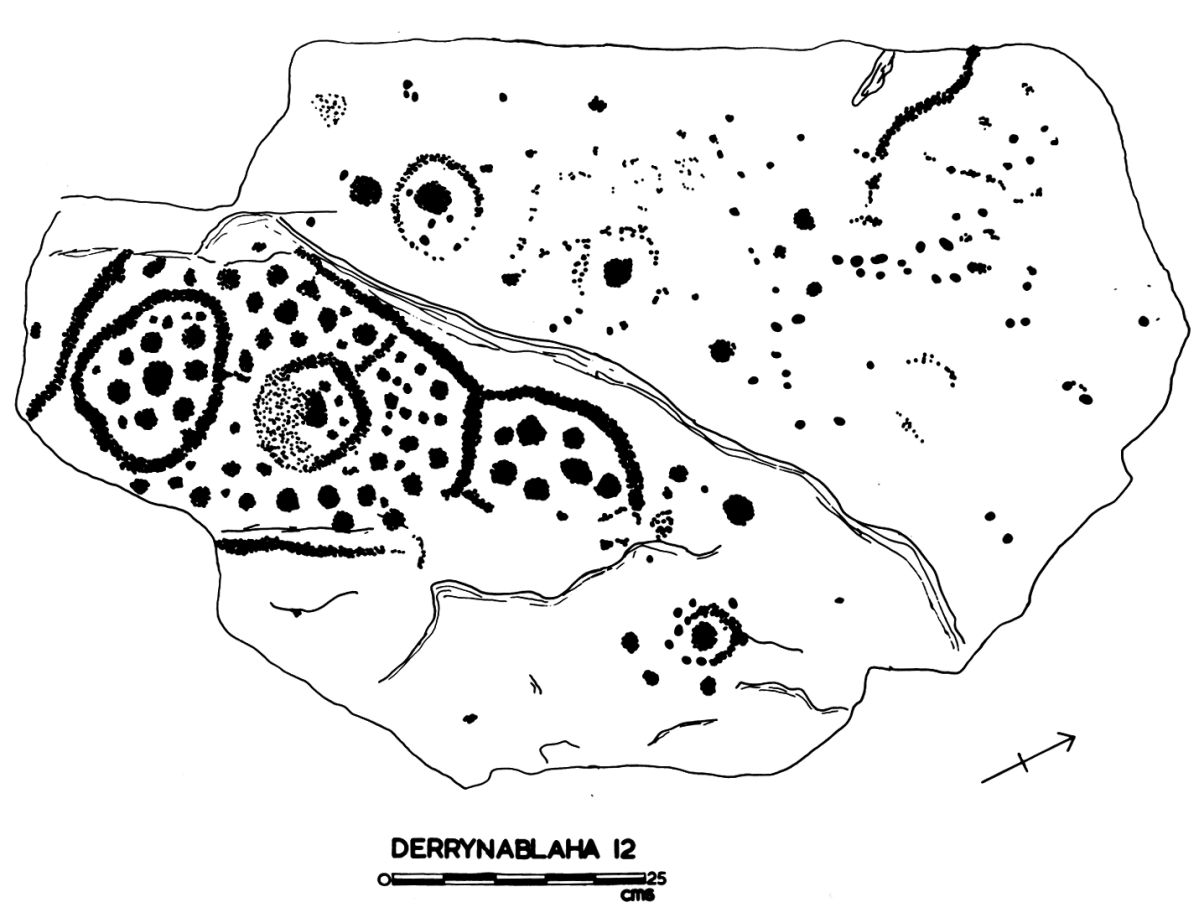

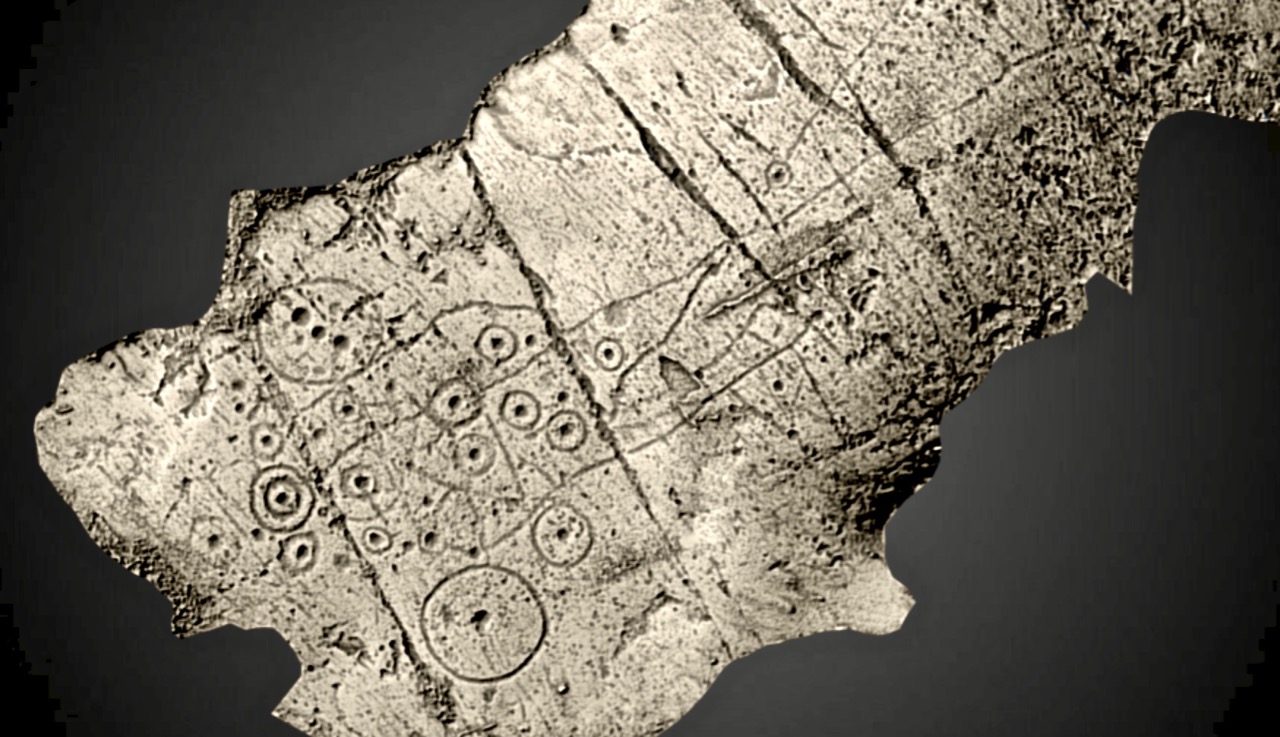

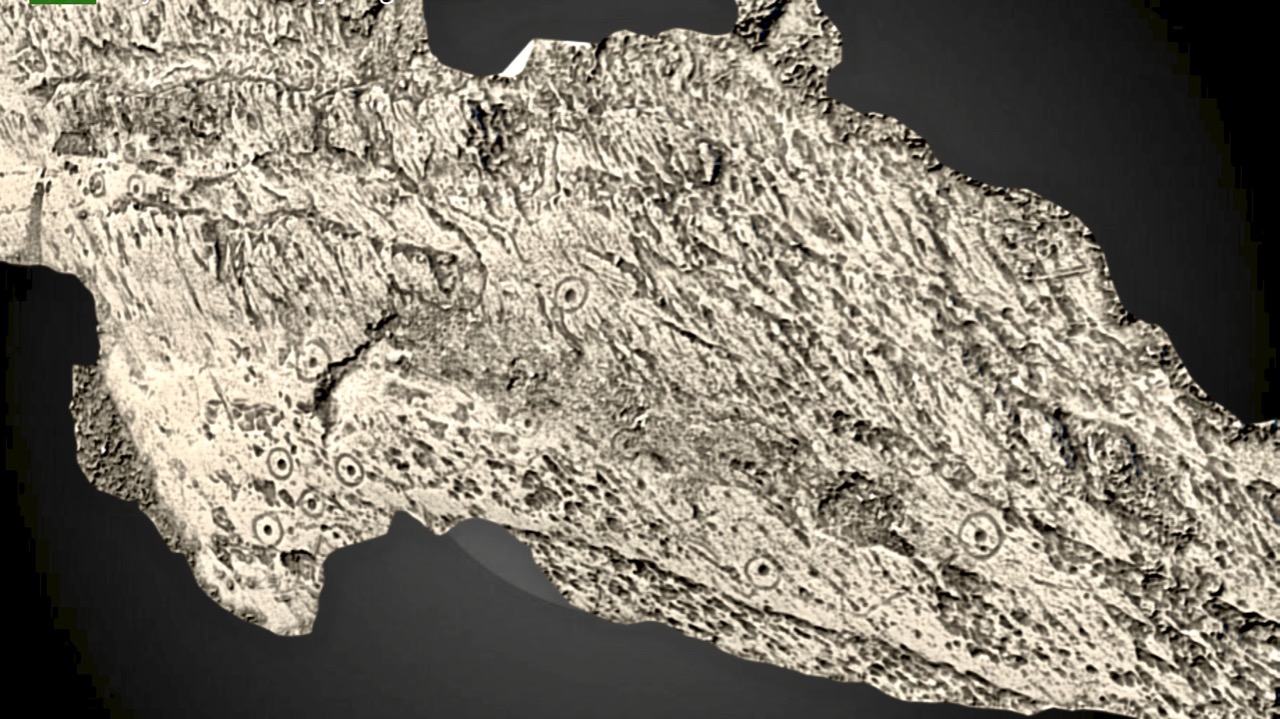

Ken’s work on rock art is astounding. We know first hand how difficult it is to get good photographs of the carvings. Many of them are covered in lichen, obscuring all the detail, and can really only be discerned in long slanting light, such as at sunrise or sunset. Ken uses both natural and artificial lighting to capture his excellent images and when we first met first we asked him how he packed all those lights up to the remote locations in which a lot of rock art is found. He grinned and opened his backpack. “This is my equipment,” he said, “It’s all I use.” Essentially his gear consists of a camera, flashes, and tripods – strategically deployed in the photograph above. If you want to see the difference between what Ken captures and what us ordinary mortals manage to do, take a look at the first two images in the post Revealing Rock Art.

it was a beautiful evening – perfect conditions to see the sun sink behind the recumbent stone. Bohonagh (above) is a complex site. Not only do we have a stone circle, there is also a boulder burial, featuring a rather spectacular quartz supporting stone and cupmarks on the upper surface of the boulder, as well as a cupmarked stone hidden in the undergrowth between the boulder burial and the stone circle. It’s been excavated.*

It was a treat to see a master photographer at work and to have Ken explain how he gets those amazing shots. From previous attempts, I knew how difficult it was to portray a scene when you’re aiming directly into the glare of the setting sun. This time I concentrated on capturing the photographer at work. Ken, meanwhile, worked his usual magic – and here’s the result, included with his permission. Not only can you see everything, including the still blue sky, but his picture captures the mysterious ambiance of the setting and the occasion.

Our thanks to Ken for an inspirational photo shoot.

* A stone circle, hut and dolmen at Bohonagh, Co. Cork, by EM Fahy, 1961