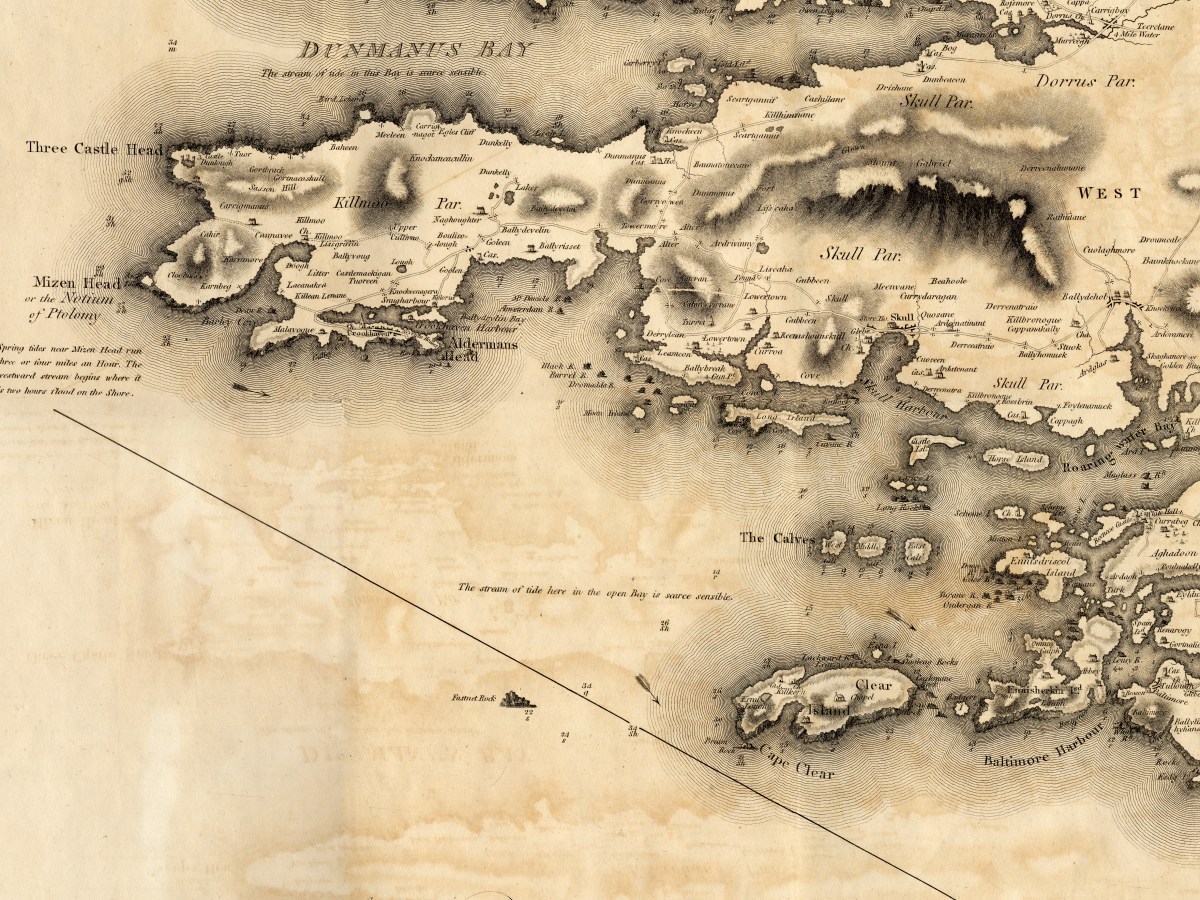

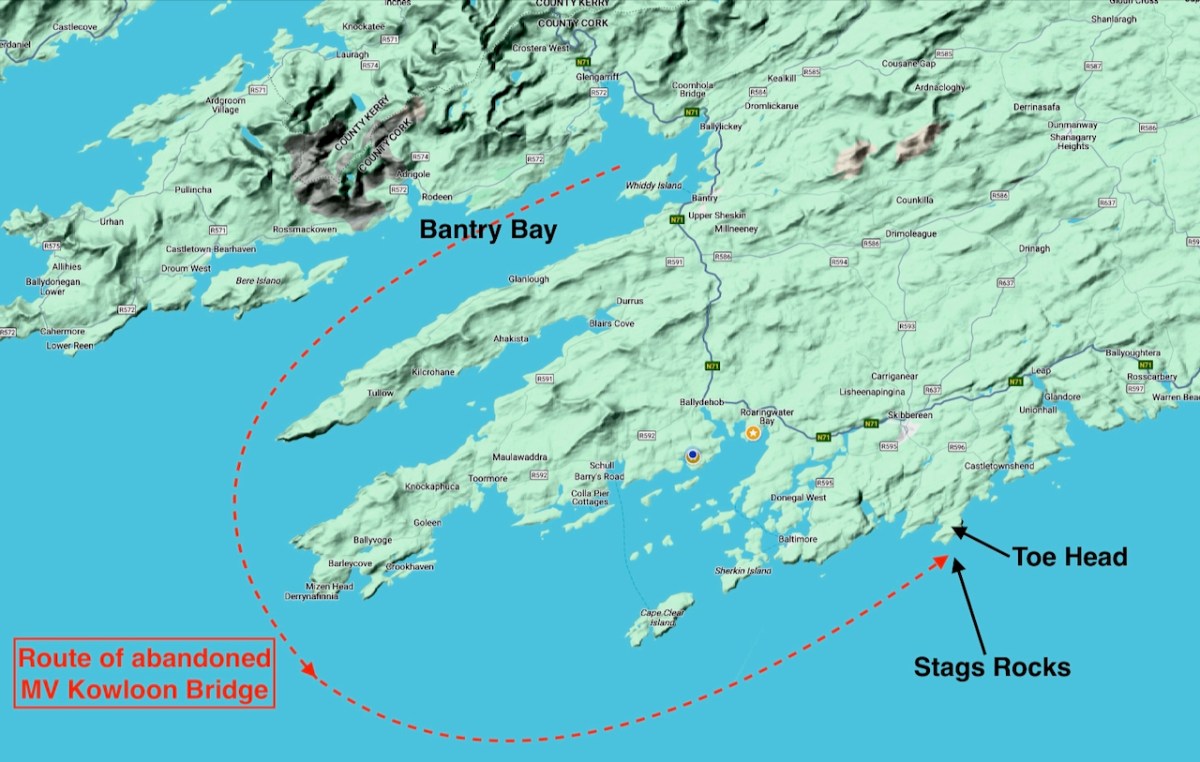

I”m going to try to be slightly less detailed this time (I find that hard!) or we will never explore the rest of Cork. This post will concentrate on the area north of the Mizen – our two other peninsulas, Sheeps Head and Beara.

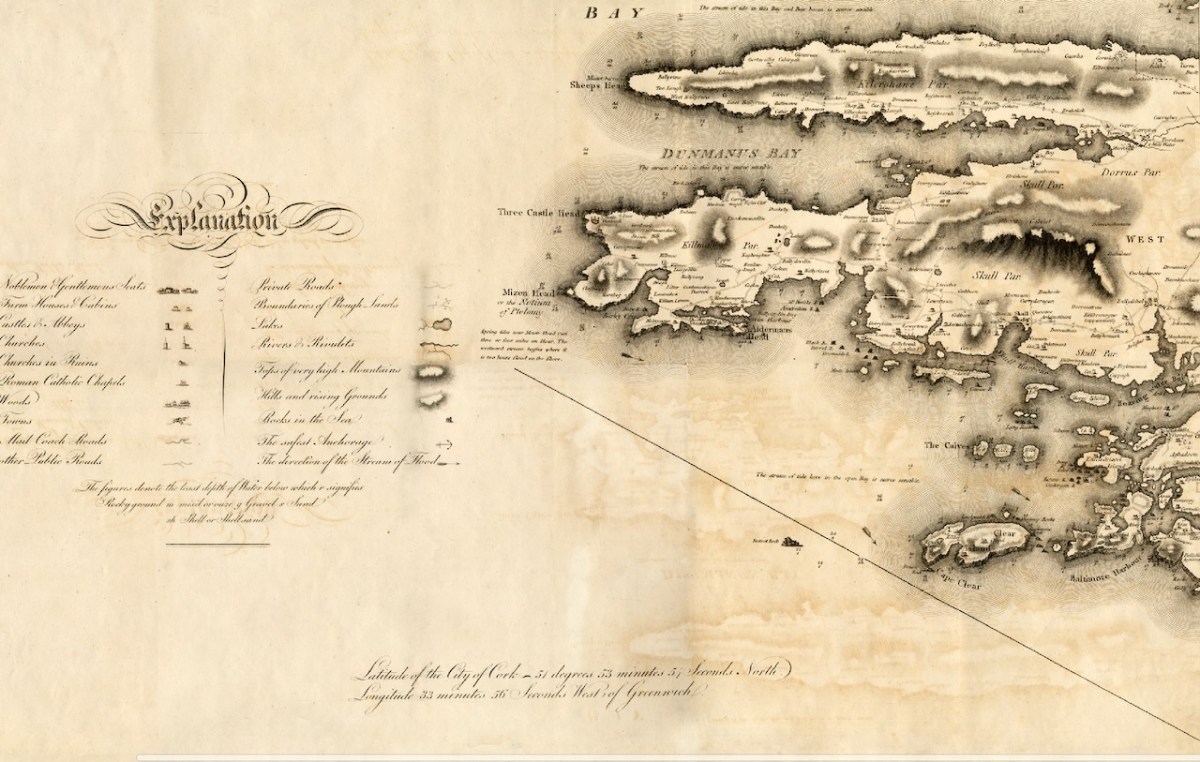

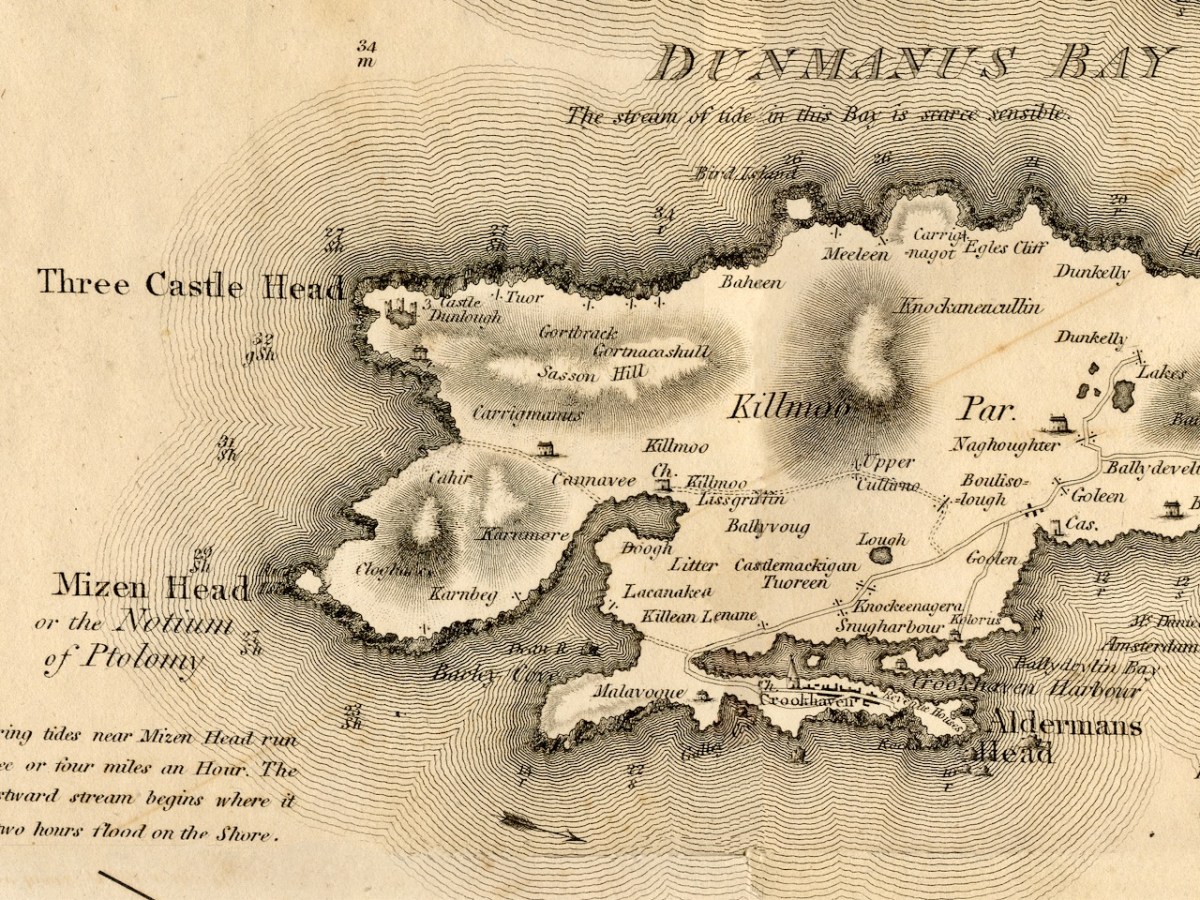

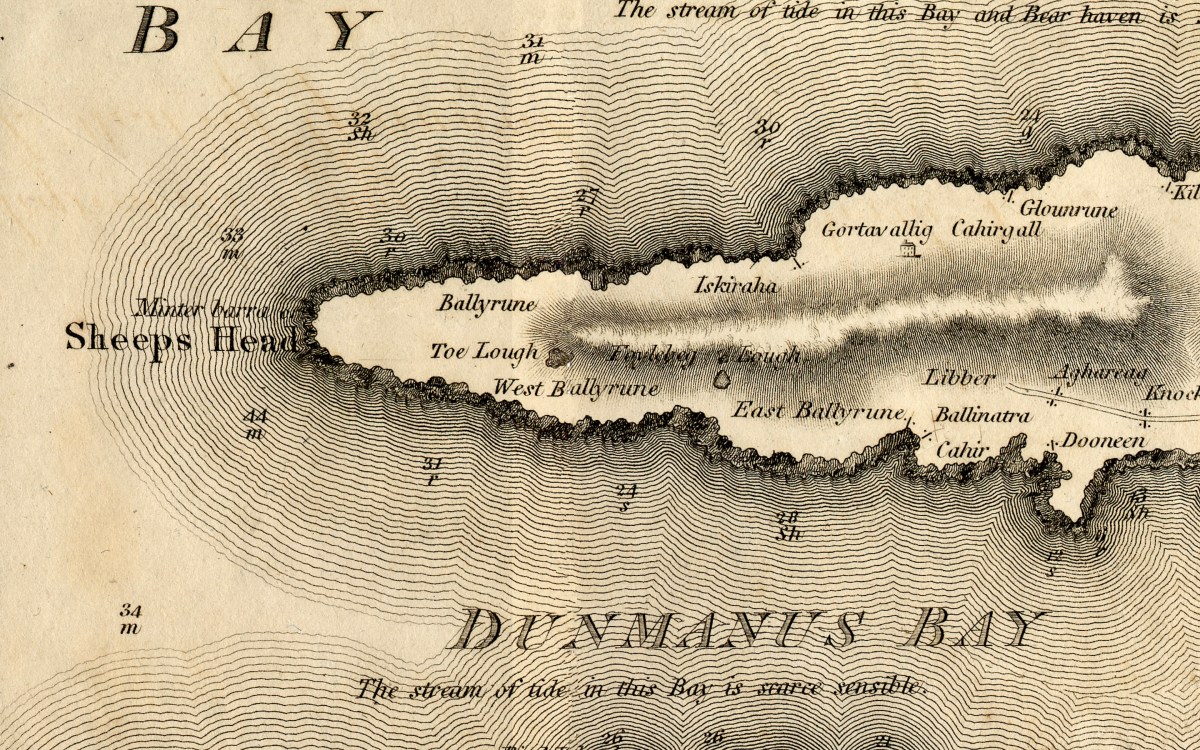

Sheeps Head (and it has an apostrophe in some maps and not in others, so I’m leaving it out) is given here as the head at the westernmost extent of the peninsula. But of course, we now call the whole Peninsula Sheeps Head. Or, if you prefer, by its Irish name of Muintir Bheara (Mweenter Varra) which means, confusingly, the people of Beara.

Besides a single house at Gortavallig, the only words on the east end of the map refer to placenames. The road does not extend beyond Dooneen. Nowadays, of course, this is a well-walked, prize winning set of trails that will bring you off road for the most part into wild and scenic country.

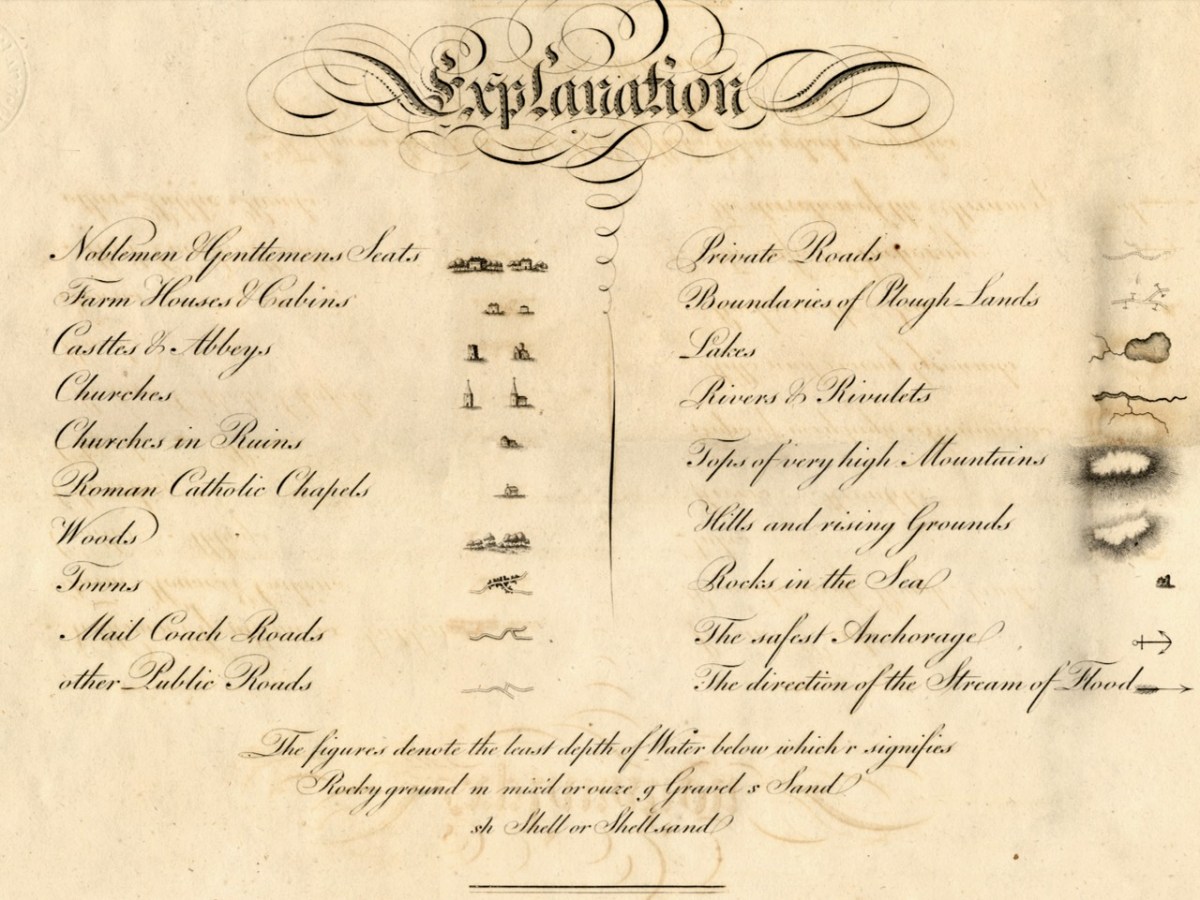

KIlcrohane and Ahakista have churches and chapels but no real communities in the 1790s. The castle near Kilcrohane is the vestigial one built by the O’Daly clan, the famous bards, at Lake Farranamanagh. There are no roads on the north side, and none crossing the Peninsular.

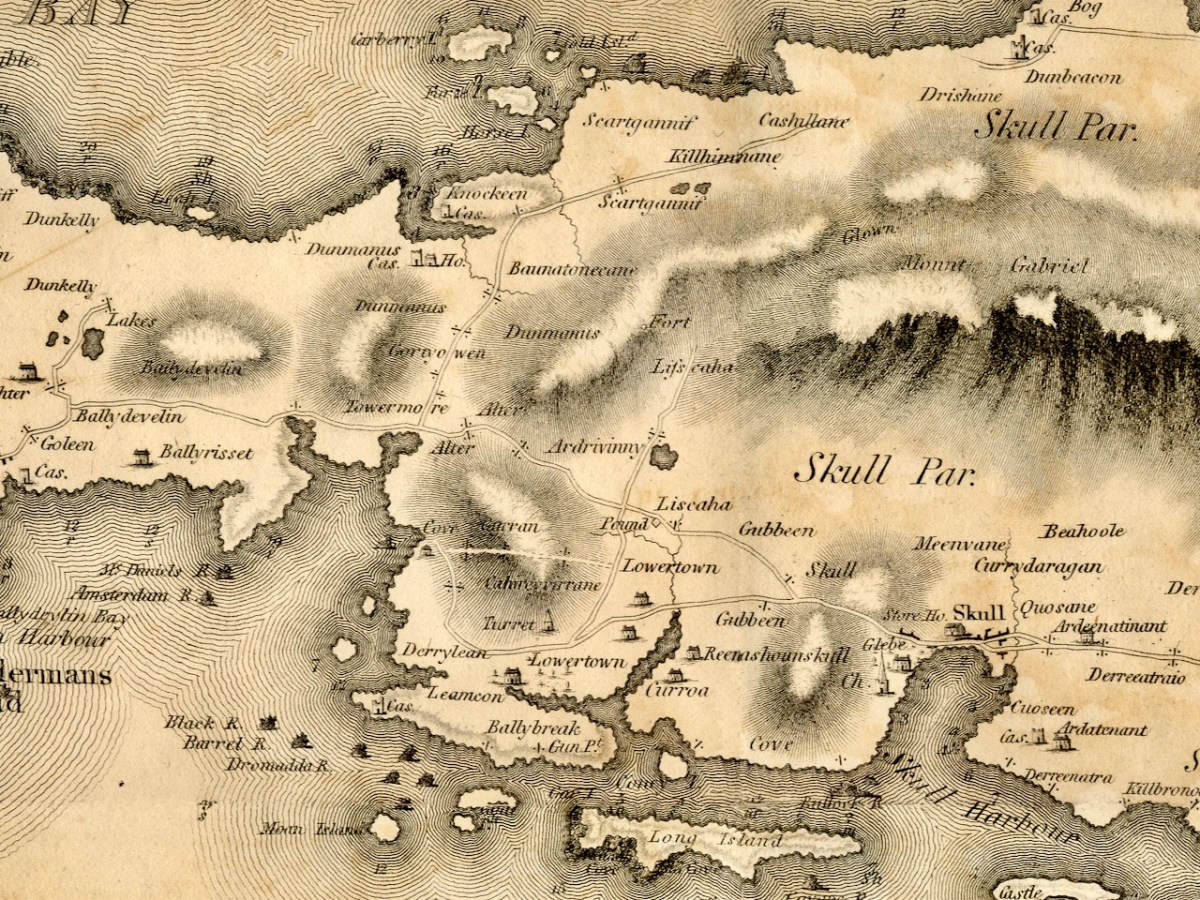

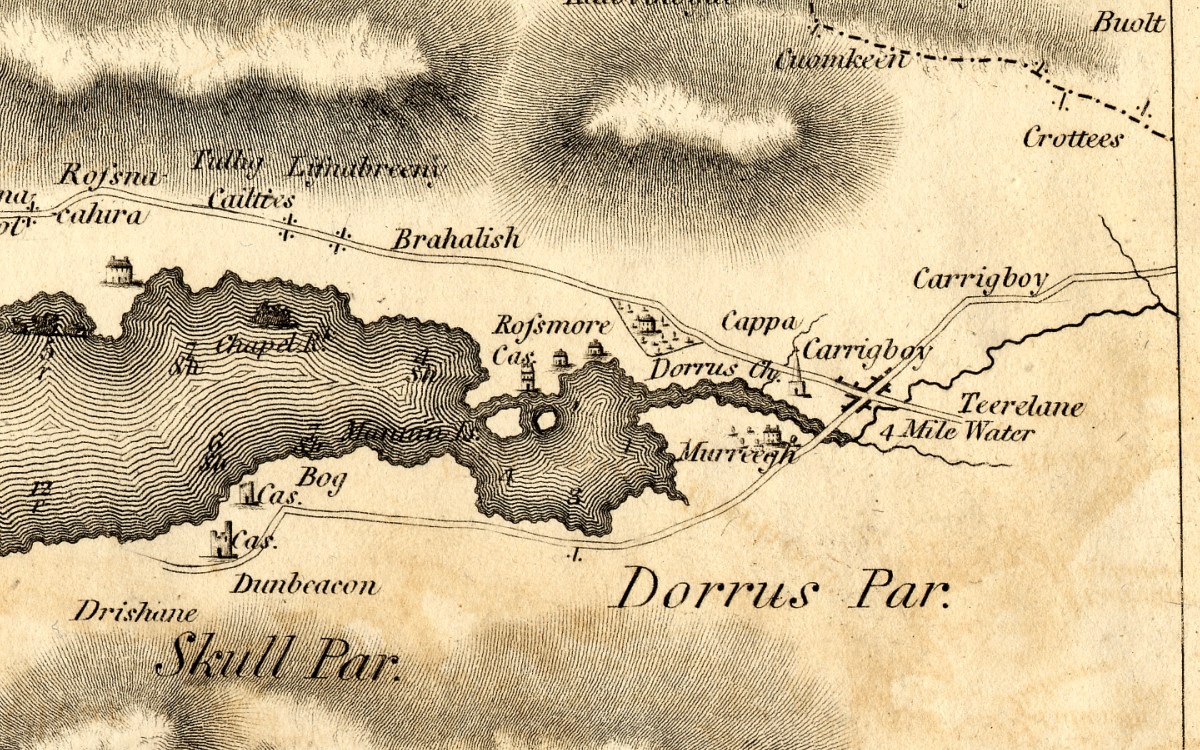

At the head of Dunmanus Bay is Durrus, shown as a community with a steepled church. The small treed estate is Durrus Court, where the 17th century manor house is still standing. The remains of Rossmore Castle can also still be seen. But here’s an interesting thing – there are not one but two castles shown at Dunbeacon! Very mysterious – there is certainly no sign of a second one now, and nothing in the archaeological record.

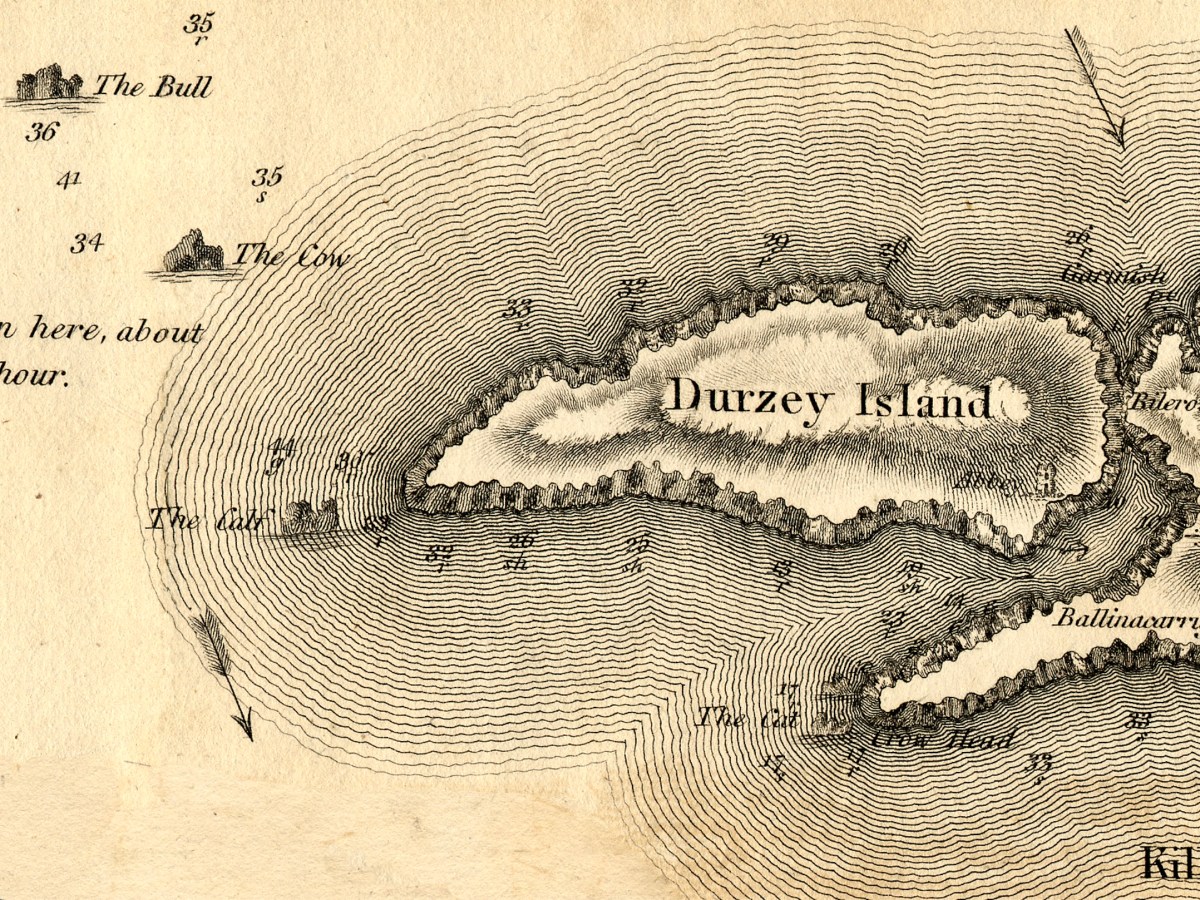

Let’s leap now, as Fionn MacCuamhaill might have done, to the next peninsular up – Beara. The full extent of it is shown in my lead photograph, and above is the eastern end and specifically Dursey Island. The Calf Rock is offshore, with the Cow further put and the storied and spectacular Bull Rock further out again. I do plan to visit it one day! Dursey is the only place in Ireland that you get to by cable car and has a tragic history. An Abbey is shown on the eastern shore. National Monuments tell us that “According to the soldier-writer and native of Dursey, Philip O’Sullivan-Beare, writing in 1621, it was a ‘monastery, built by Bonaventura, a Spanish Bishop, but dismantled by pirates'”.

The western end of the Peninsula is mountainous. A road extend along the southern side but not the northern. This is one of the few places in Ireland we have a very old map to make comparisons. Take a look at my post Elizabethan Map of a Turbulent West Cork and Elizabethan Map of a Turbulent West Cork 2: The Story, for a lively take on mapping this part of Ireland 200 years earlier.

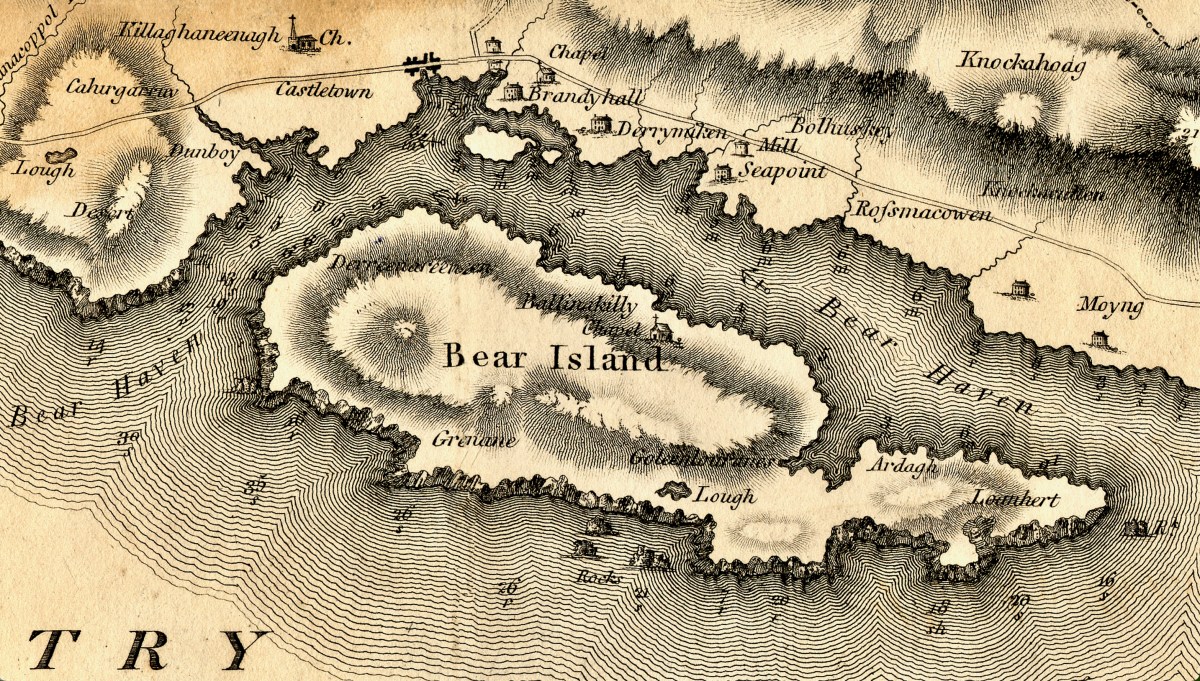

Bear Island is featureless apart from a chapel but Castletown (more properly known as Castletownbere or Castletown-Berehaven) is shown as having a town or village and several substanital houses, a mill, and a church with a steeple. Interestingly, the castle at Dunboy, the siege of which is chronicled in the older map, is not shown at all in this one.

Moving eastward, very little human activity is noted on the map, but Hungry Hill is there and Adrigole Harbour. The dotted line marks the division between Cork and Kerry.

Then, there seems to be a bit missing – Glengarriff (or here, Glengarruv) Harbour is surrounded, then as now, by substantial forests. The only road to Kenmare at that time was the Priest’s Leap, even now a death-defying and vertiginous climb.

I’ve blown up the Ballylickey section as it holds particular interest for me – here depicted is the home of Ellen Hutchins! There’s a large house, surrounded by trees, on the banks of the Ouvane River. This is especially exciting as Ellen was living here at exactly that time! Born in 1785, she was botanising and making all kinds of discoveries until her untimely death at only 29 in 1815. After the sparsely annotated Peninsulas, it’s interesting to see more houses noted as we near Bantry.

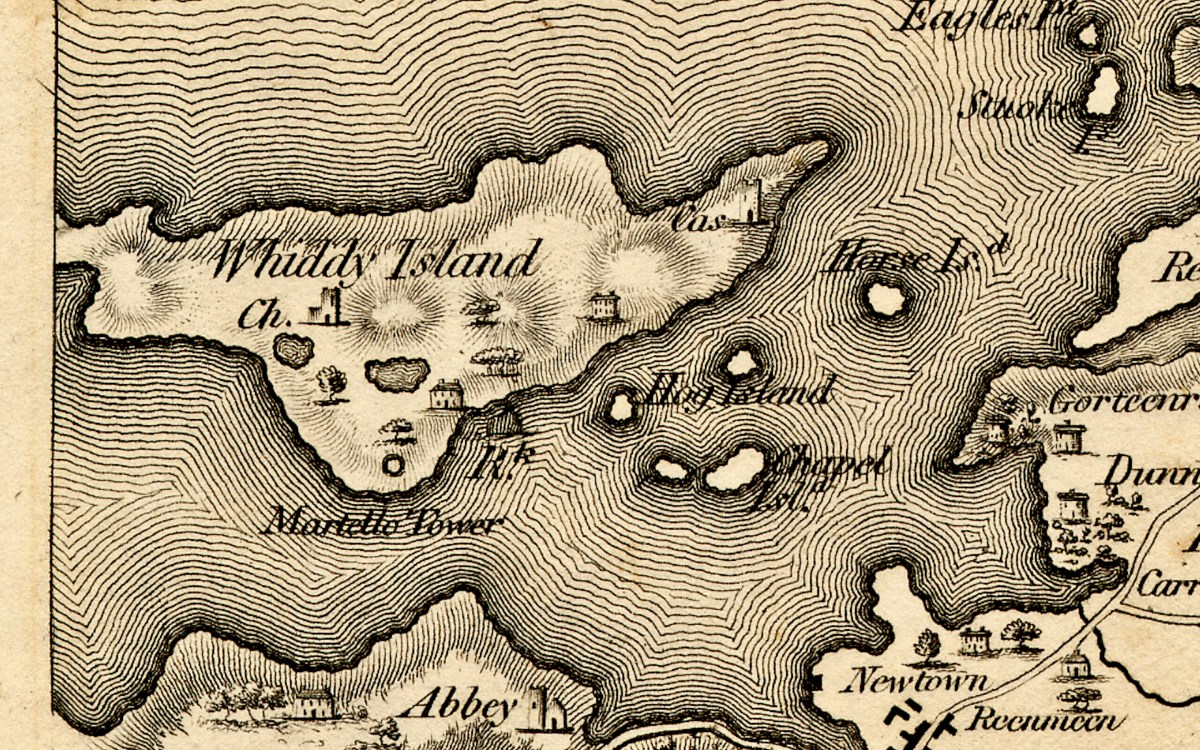

Bantry is shown as a large town – with Bantry House, built on the early 1700s, dominating the landscape just as it does today. The Abbey has disappeared (it was a Franciscan establishment) but has given its name to the Abbey Graveyard at the southern end of town. We’ll finish with Whiddy Island and a genuine mystery – note the Martello Tower (below). There were actually three circular fortifications constructed on Whiddy after the abortive invasion by the French in 1796. Known as the West, East and Centre Batteries (or ‘redoubts’); this is probably the Centre one. They were very solidly built and can still be seen.

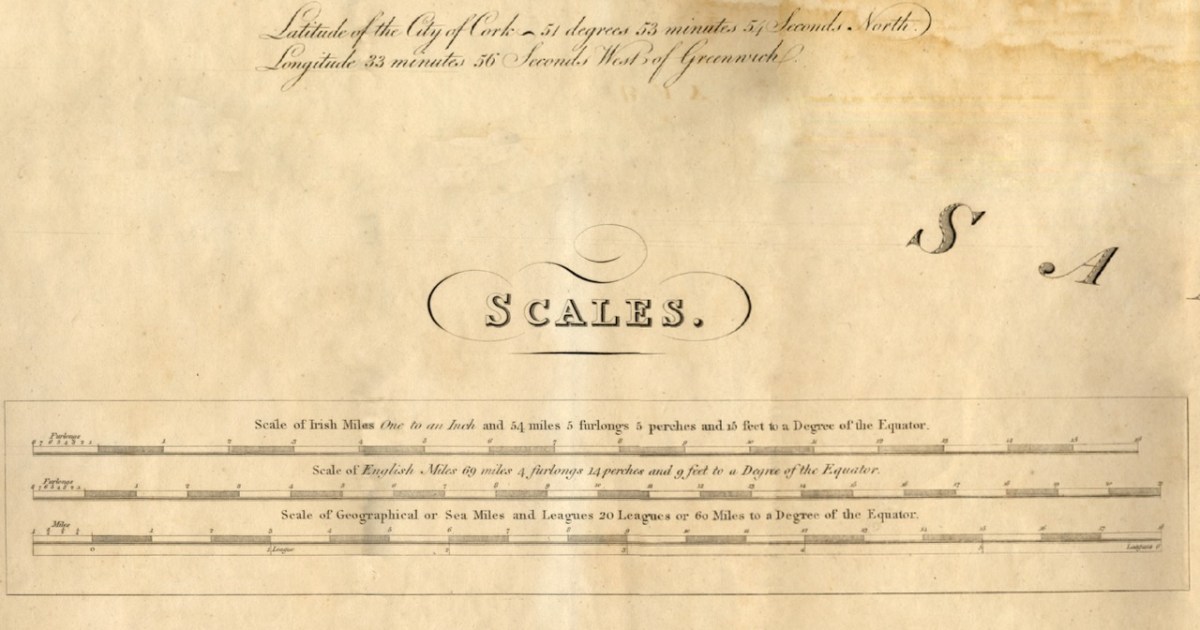

We know this map was done in the 1790s, and these redoubts, like the Signal Towers dotted along the coast, were built to warn of another French incursion and to defend Bantry Bay. The signal towers were built around 1804 and abandoned by 1815 after the Battle of Waterloo. None of them is noted on the Bath map, consistent with our understanding that the Cork map was completed in the 1790s. Martello towers date to the same period – the first of them were built in 1804, mostly along the east coast. The only actual Martello tower in this area is on Garnish Island. It was built in 1804/5 and does not show up on the island in the Bath map – see Glengarriff Harbour, above. The Whiddy Batteries are shown on the National Monuments records as dating to 1804 to 1807. They are round – more like the shape of a martello than the tall rectangular signal towers that were built around West Cork. But was the term Martello common at this time? Might this be a later addition to the map? Although it was completed in the 1790s it was not published until 1811, allowing for the possibility of editing and changes. Anybody have any comments on this – it’s a head-scratcher!