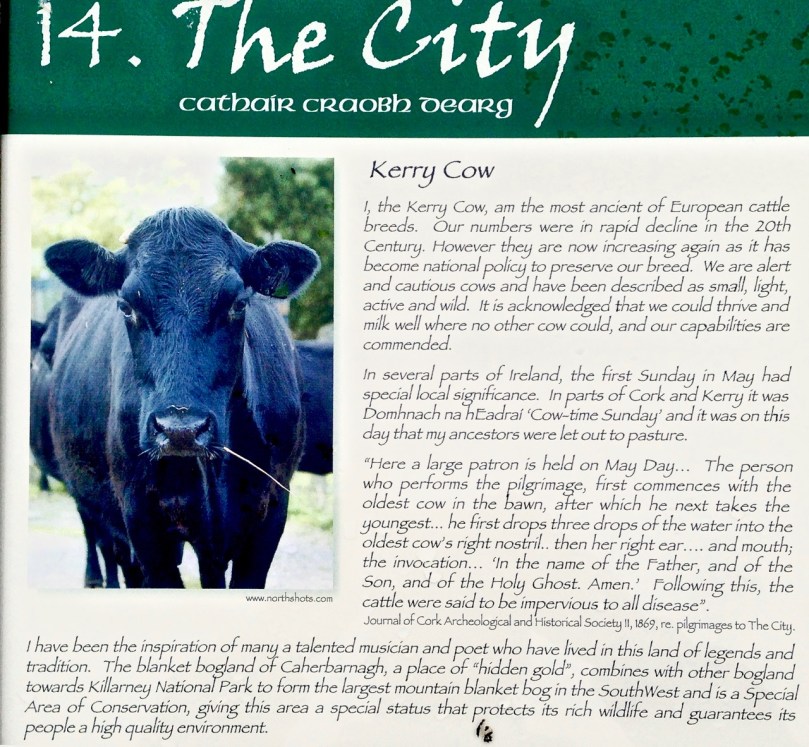

It’s May Day, and we’re in Ireland, so it’s no surprise that we should encounter a talking cow. We are in Kerry County and it’s a Kerry Cow that’s doing the talking. This is an ancient breed of cattle – probably the oldest in Europe – so our cow has a lot of stories to tell.

We found the cow – or, at least, the story she has written – in the City of Shrone. What sort of a metropolis is that, you wonder? It’s a pretty diminutive one: it’s almost certainly the smallest city in the world. It has no skyscrapers and no traffic jams…

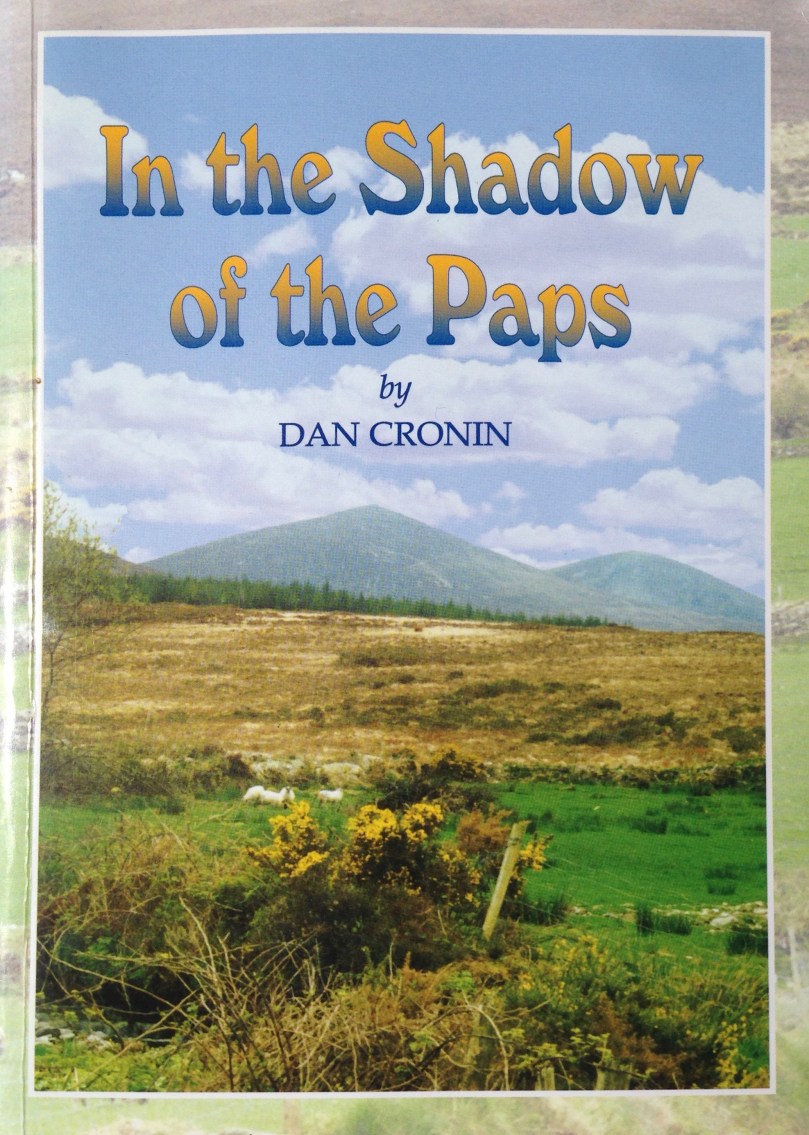

Shrone does, however, have a long, long history. According to the local expert on this subject, Dan Cronin, …Historians have satisfied themselves that The City was one of the first places in Ireland to be peopled. It was here on a barren elevated site that the Tuatha Dé Danann had their base established, naming the mountains at whose base they had settled, Dhá Chich Danann, The Two Paps of Dana…

Dan’s book (published in 2001 by Crede, Sliabh Luachra Heritage Group) is the definitive work on The City, The Paps, and the life and traditions of the Sliabh Luachra – which is the name given to the mountains and rushy glens on the borders of Cork, Kerry and Limerick. It’s an area which has long been famous for its traditional music: at our own Ballydehob Fastnet Maritime and Folk Festival – coming up in June – two of the most notable musicians carrying that living tradition, Jackie Daly and Matt Cranitch, will once again be in residence.

Matt Cranitch and Jackie Daly in Ballydehob, at last year’s Fastnet Maritime and Folk Festival

Meanwhile, back in the City, we have deliberately timed our visit for the First of May: this is Shrone’s big day! The City is 50 metres in diameter – it’s a very ancient stone cashel or ring fort. The Irish name for it is Cathair Crobh Dearg, meaning ‘Mansion of the Red Claw’. On the western side of the finely preserved four metre thick stone walls is an entrance (known as the gap), and anyone coming in that way has to pass by a holy well. Today is the Pattern Day for the well, and elaborate rounds are performed, culminating in taking the holy water. There is much to do with cattle at this site: the Tuatha Dé Danann are said to have originated in Boeotia – the Land of Cattle – in Greece, and the well water is notably good for cattle, especially on this day. The well was formerly in another site nearby and there cattle were driven around it to ensure good health and fertility for the herd. Farmers still take water from here and sprinkle it on their animals.

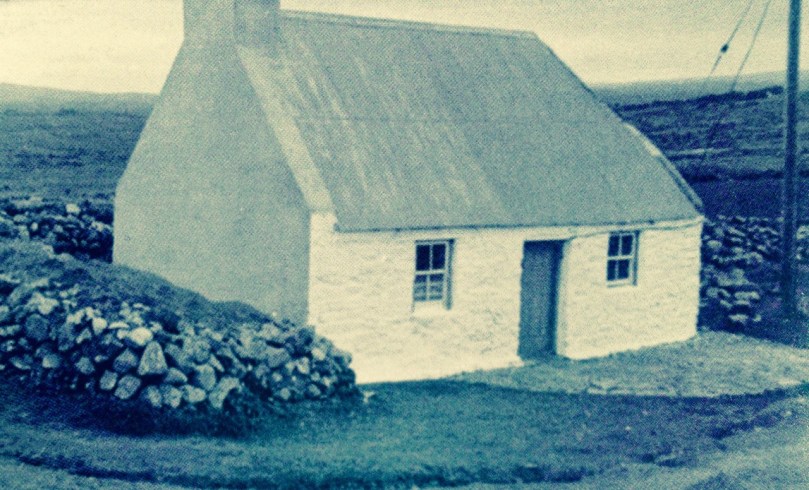

Satellite view of The City of Shrone: the circular cashel wall is clear. On the left is ‘The Gap’ and the holy well. Beside ‘The Gap’ and inside the city is the ruin of Paddy Quinihan’s House (below and bottom): in the 1930s he was the deerhough (caretaker) of the holy well

Today is Lá Bealtaine (pronounced Law Byowl-tinneh): the Irish word might refer to the ‘Fires of Baal’, reflecting a tradition of lighting fires on hilltops or in sacred places. In Ireland it was important to drive cattle through, or by, the flames as a purification ritual. As May Day was usually the first day that the animals were brought out of byres and sent to the summer pastures (booleys), it makes sense that the purification would have taken place at this time. So we have the various seasonal elements of water and fire connected with cattle and their health and fertility: it’s no wonder that our commentator at Cathair Crobh Dearg is a cow!

The holy well water at Shrone is good for animal health and fertility: Robert gives it a try!

The City of Shrone is below the Paps. According to Cronin, the early celebrants – the Danann – …were wont to go up to the top of the Paps for the fertility and immortality rituals. Fragments of ancient pagan altars still remain to this day. Petitions were made to the gods for fertility for man and beast, good return from the land, good crops and fodder. Even today, 4000 years later, several small offerings are placed on ledges near the ruins of pagan altars on top of the Paps Mountains for health of the family and of cattle and for fertility… Many of those acquainted with this old pagan custom have remarked on the peculiarity of its perseverance and continuity… I would like to explore those high parts but, ‘on the day that’s in it’, they are not even visible, and it would be unwise to venture into such a shrouded domain when, at this turning point of the year, the spirits of the hills might be abroad…

The way to the Paps: it’s unwise to venture there when you can’t even see the summits of the sacred mountains…

Cronin again: …So the May Day or Lá Bealtaine festivities were held each year and the years rolled by. On May Day, The City and its surroundings were a hubbub of activity. The music of pipes and fiddles re-echoed from the hills and valleys, and the lowing of cattle mingled with the sweet music of the harp. Jesters and jugglers plied their respective trades, with everybody trying to make themselves heard. It is very evident that ale was brewed here in plenty. Champions were performing feats of valour, while throngs of admirers looked on… What will we find happening today, May Day, at the smallest but most ancient city in the world?

Our Lady of the Wayside guards the sacred site now (above) while (below) preparations are made for the Bishop’s visit

It’s still a sacred site and the crowds still come. But it’s Our Lady of the Wayside who looks out over the City walls now. A Mass is performed within the Cashel on May Day afternoon. This year the Bishop of Kerry is in attendance, as is a devouring Kerry mist. I listen in vain for the echoes of harp, pipes and merrymaking. The City of Shrone on a cold, damp First of May seems a desolate place – yet an absolutely fascinating one. The pilgrims visit and the curious passer-by (like me) pauses to drink from the well. As always here in Ireland, history is writ large on the landscape, and continuity is assured both through holy ritual and piseogs…

Pilgrims leave their marks on a ‘Neolithic altar’ under the statue of Mary

Another record of the day at The City can be viewed on Louise Nugent’s page, here. Amanda has covered the holy well at Shrone here. Voices from the Dawn website published an interview with Dan Cronin, who wrote In the Shadow of the Paps.