We are past November Dark – traditionally a ‘low’ time of the year when the effects of the approaching cold months begin to displace autumnal skies and spectacular sunsets: the term traditionally refers to the appearance of the new moon of the month (which happened this year on the 4th), but is probably inspired by the preceding nights when no moon is visible. For us at the moment, on the shores of Roaringwater Bay, the dark time is emphasised by a constant pervading mist which clings and covers everything in films of moisture, especially the myriad cobwebs on the gorse bushes which surround us. Gone – for now – are our fine views out across to the islands, and there is a feeling of being marooned and suspended in a lifeless grey tract which encompasses sea and sky.

November Dark has brought with it tragedy to our garden. In explanation, I should first paint the idyllic picture of what we like to call our ‘peaceable kingdom’. For many years we have considered this domain a haven. Do you remember our fox – Ferdia – who was a constant companion to us in the first few years here at Nead an Iolair? He visited on a daily basis – often waking us by barking outside our bedroom window at dawn, and presided over a mixed community of birds and animals who share our territory – without any conflict.

Ferdia was happy enough to co-exist with the bird and pheasant families, the rats and mice, and the occasional cat that dropped in. I have a memory of fox and cat sitting side by side on our terrace, clearly having a conversation with each other: I would like to have eavesdropped, but whatever mutual language they share was not available to me! Ferdia vanished from our garden a few years back – gone to his happy hunting grounds no doubt; but the pheasants have remained with us through much of the decade we have been here.

In the upper picture Finnbarr and his young wife, Fidelma, patrol our garden some five years ago. The lower picture was taken just before the start of the Pandemic, in March 2019. The couple have been a daily feature of life outside Nead an Iolair. They always appreciated feeding time, when they got a share of the seeds I put out on our patch for the many bird visitors, small and large. The picture below taken during the summer of last year shows a family group: pheasant chicks have been seen but rarely.

The idyll abruptly ended yesterday, when a bomb hit the garden – in the form of a small but fierce force of nature: only inches long but terrifying. I glanced out of the window where, minutes before, the two pheasants had been foraging as usual along the stone boundary wall. I was shocked to see Fidelma lying on her back, wings flapping, being dragged along the ground: there was a commotion among the small birds and Finnbarr had vanished. At first I could not see the attacker, but as I rushed outside I caught a glimpse of brown fur with a hint of white and black. My first thought – a rat! – could not have been borne out: we have lived side by side with rat families for years: they only ever appear to share the bird food, and are never aggressive.

You can see the conditions that prevailed on this worst of days from Finola’s picture (top), taken from indoors through the windows. And – below that – the brazen culprit, who danced around the garden at breakneck speed, very ready to threaten me if I made a wrong move! It was our first sighting here on our land of an Irish Stoat. Having now read the books, I know in hindsight what a shocking phenomenon had hit us. Although fearing the worst, I quickly removed Fidelma to an indoor refuge and then watched the rampaging of this fur powerball traversing our territory at lightning speed; leaping from walls, trees and bushes and aiming for any likely food source.

Finola has done her best to clarify the images in the photos she rapidly took through streaming wet glass (above) on this appalling day. The weather did not in any way impede the progress of the animal which circumscribed our whole acre, it seemed, in record time.

. . . The Stoat is often called the Weasel in Ireland, but although the weasel (Mustela nivalis) is very similar in appearance to the stoat, it is not native to Ireland and has never been introduced here. In Ireland the stoat or ‘weasel’ was regarded as a very intelligent animal, but also vengeful. For example, since they were believed to understand human speech, if a stoat was encountered the correct thing to do was to greet them politely. In County Clare the custom was to raise one’s hat in greeting, or even to bow. The person who insulted them, on the other hand, or pelted them with stones, could expect to lose all their chickens before too long. Deliberately killing a stoat was most unwise, since it caused all the deceased animal’s relations to descend on the house of the culprit and attack with great savagery . . .

Ireland’s Animals – Myth legends and Folklore, Niall Mc Coitir, The Collins Press, Cork 2010

The Duchas Schools Folklore Collection – gathered in the 1930s – has numerous entries referring to the stoat. Above is an example from Co Carlow. When I was sifting through these, I was struck by the fact that similar stories about stoats are repeated over and over again, but from different parts of Ireland. I could write a volume based on these accounts, but will choose only a few:

. . . One time there was a girl who was very fond of going to the seaside. One day she went to the seaside and lay down and fell asleep. Ten weasels went down her throat. So she awoke when the last one was going down. She went to the doctor and the doctor said she would need to undergo an operation and then she would die. One day she was going to the shop and her granny knew all about cures. So she went into the granny. Her granny told her to get two pounds of salt and eat all the salt and go to the seaside and drink no water and keep her mouth open and the weasels would have to come out for a drink. So this she did. The weasels came out for a drink. The girl counted them. There were ten in it and the girl came home cured . . .

William O’Donnell, Cabra Glebe, Co Donegal

. . . One day long ago two men went to cut the meadow with scythes. They cut away for a while until they came to a weasel’s nest where there were four young weasels out of the nest and left them near by on the ground. After a while the mother of the weasels came home and found her young on the ground and was very angry, She hesitated for a moment and then understood what the men had done. Now the men had had a can of milk with them for a drink which they left near the weasel’s nest, the old weasel saw the can and went to see what in it. When she saw what was in it she spat into it because a weasel’s spit is poison. When the men saw this they were terrified and put back the young weasels into the nest, and the old weasel was pleased and went back and upset the can and spilt the milk from fear the men would drink of it and be poisoned . . .

James Gormley Senior, Aged 82, Commeen, Co Roscommon

Note that the term ‘Weasels’ is used far more often in these accounts than ‘Stoats’. There can only be the one animal, however, as there have never been true ‘weasels’ in Ireland. The story above, from Co Roscommon, is the most common of all ‘weasel’ tales in Ireland, and variants of it have been recorded from all parts.

. . . Many years ago an old woman lived by herself. There was a nest of weasels under the hearth in the house in which she lived and every day the old woman fed them until they became quite tame. When the young weasels were reared they went off but the old one remained in the hearth. One day the woman was sitting by the fire when the old weasel came out and sat with her. The weasel was continually looking up the chimney and at last the woman said “What the dickens are you looking at?” and at the same time looking up herself. She saw a little bag hanging in the chimney and took it down. To her surprise and joy she found it was full of gold. This was the weasel’s reward for her kindness to her and her family . . .

Mrs L Millett, Fiddaun Lower, Inistioge, Co Kilkenny

. . . The Swarm or Drove of Weasels: the following story or rather fact come from a reliable source to wit a teacher in Ballyshannon. In the end of August or about that time some distance outside Ballyshannon a great whistling was heard as if a number of little birds and a mighty drove of Weasels was seen heading for the mountains. An old man said that he heard that weasels used make for the mountains during the Grouse Season. The Priests housekeeper saw or heard of the same thing in Antrim . . .

J Clarke, Navan, Co Meath

. . . Some time about forty years ago there were children playing on the side of a hill and they saw a few weasels. They started to run and cry. They looked round and saw thousands coming after them. Only they got away the weasels would have devoured them . . .

Written by Kathleen McKenna Bragan, Co Monoghan 25th November 1938

I couldn’t resist that little foray into weasel stories from the Folklore Collection. There are many many more pages full of them! Interestingly, stoats are a fully protected species in Ireland. If stoats are proving a problem, by killing chicks or other domestic animals, you must solve the problem by using good fencing; it is illegal to kill a stoat.

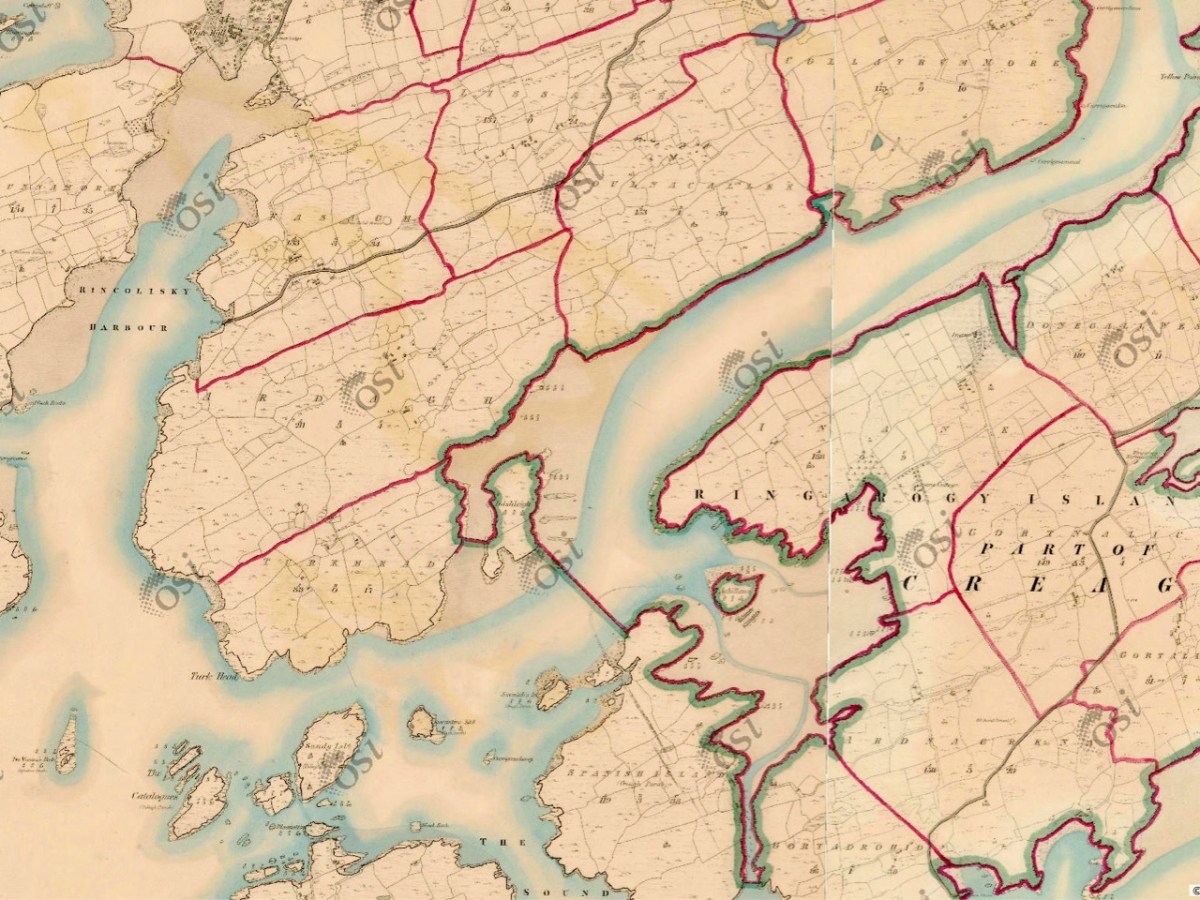

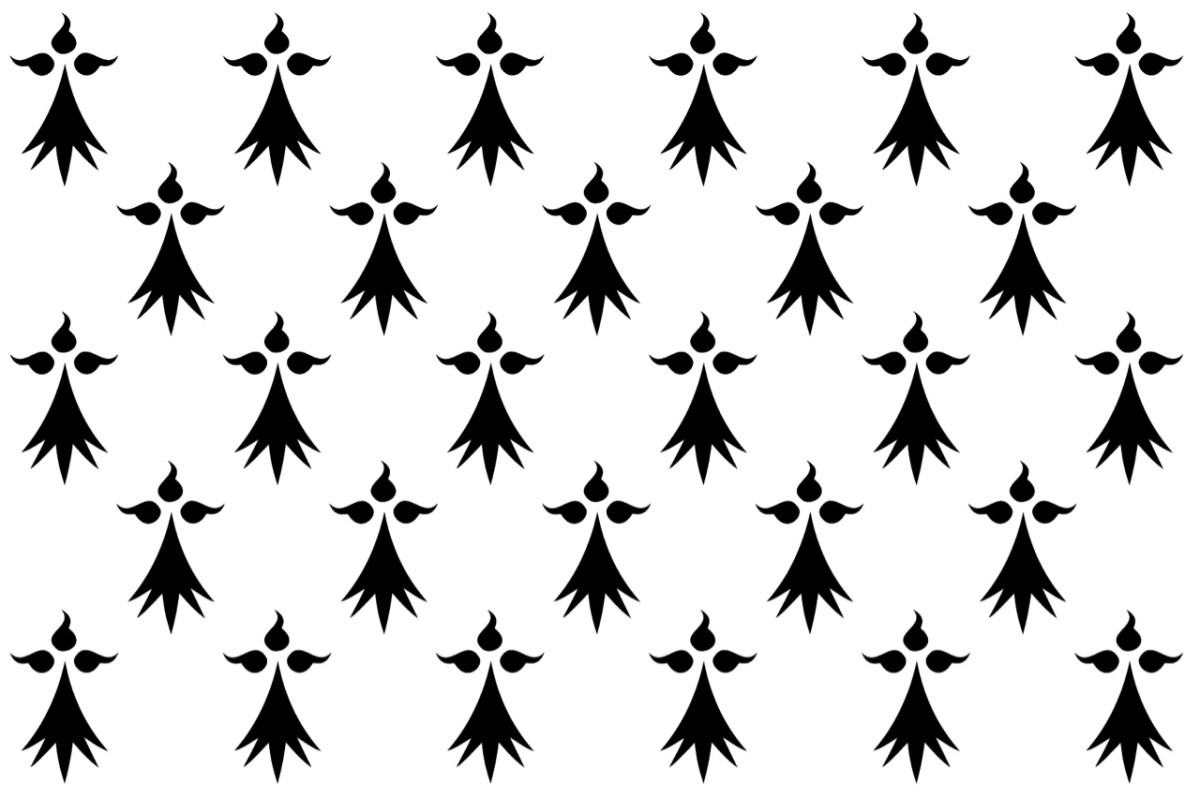

A possible reason for the attention which stoats attract in folklore is the fact that they can change colour, which adds a sense of the supernatural to them. In countries which have harsh winters the coat of the stoat becomes white in those months, offering a level of protection in the open landscape. The fur from the white – or ‘winter’ – stoat we call ermine, and the white fur is considered so precious that only royalty or nobility traditionally wear it. In the drawing above, the white stoat is wearing a cloak on which are printed the symbols of the flag of Brittany (below), which was an independent kingdom in medieval times. The white background represents the ermine fur, and the black markings are said to be based on the black tip of the tail which the animal retains, even in the winter.

Here (above) is another example of the Breton ermine representation: a finely worked silver antique brooch. In Ireland, the species of stoat which has evolved – Mustela erminea hibernica – does not usually turn white in winter, although examples have been noted. The animal is said to have been resident in Ireland from the post-glacial period and, in the present day, the population numbers are unknown: it is not a threatened species.

In spite of our attempts to care for Fidelma, she did not survive. Sadly, I decided to let Nature have her way and laid the body close to a fox-track above the house. Later, I noticed an assembly of corvids gathered in the area. When I returned there in the evening all traces had gone – just a few scattered feathers told the tale.

This morning, Finnbarr was absent from the garden. I did catch a glimpse of him wandering the distant pastures – forlorn and bereft. At least, those are the feelings my human soul projects onto him. He will find another mate, of course, and we hope they will continue to share our little bit of paradise. We will keep a lookout for unwelcome visitors, but we will always have to pay our respects to the ‘weasels’. If our stoat does return we will have to honour him with an Irish name: I am inclining towards Fiáinín – which means Little Wild One.

Lady with an Ermine, painted 1489–1491 by Leonardo da Vinci. The subject is said to be Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of Leonardo’s Milanese employer, Ludovico Sforza. The Ermine is symbolic, rather than realistic – in fact it is pictured much larger than in real life. It has been suggested that the ermine in classical literature relates to pregnancy, sometimes as an animal that protected pregnant women. Around the time of the painting’s creation, Cecilia was known to be pregnant with Ludovico’s illegitimate son.