First of all, a HUGE thank you to all the readers who sent me such kind messages of support on my last blog. I am normally very good about responding to comments, but moving house took its toll on my time and energy and I just never got to it. But I want you all to know that I read and appreciated SO MUCH every single message and I felt totally supported by this Roaringwater Journal community we have built together.

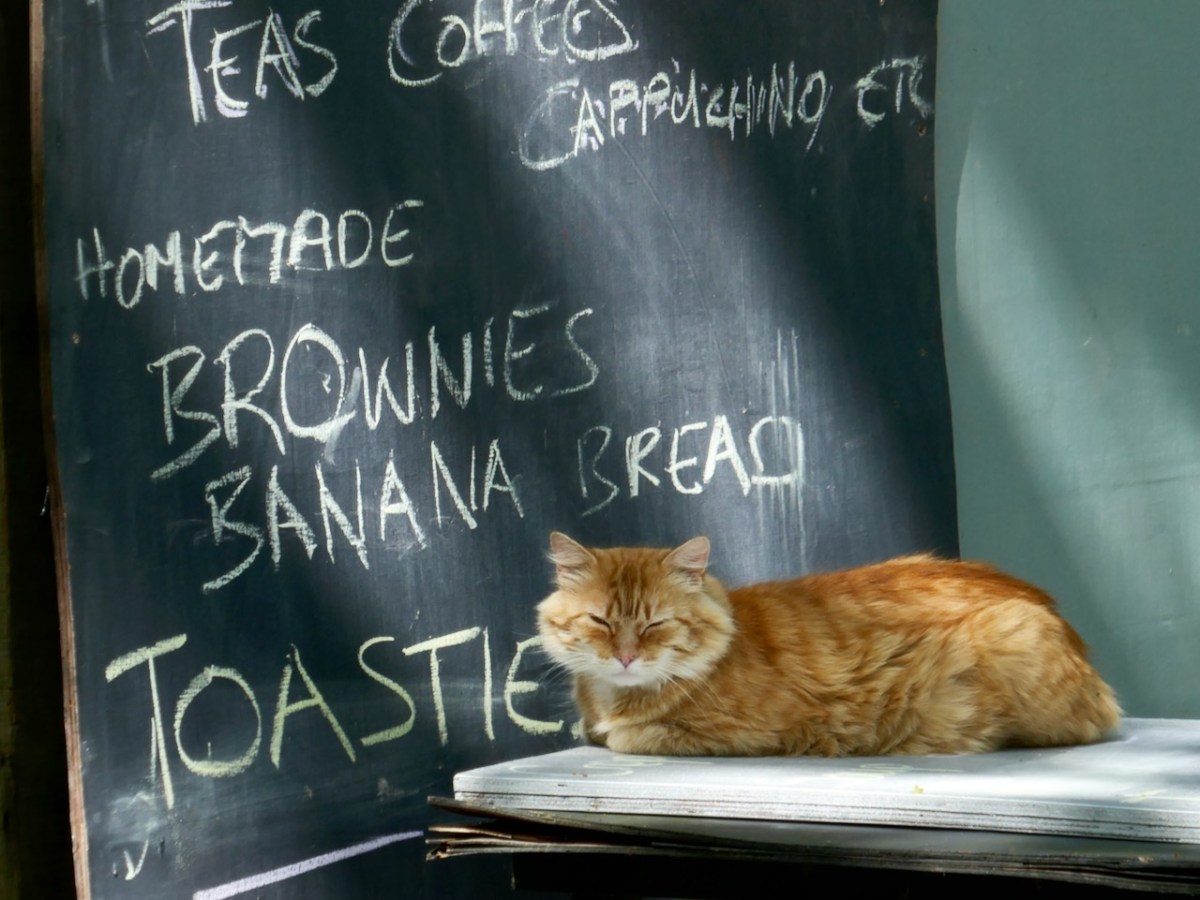

So here I am now, happily settled in Schull, looking back on what we have written about this wonderful village over the years. And what we have eaten as well.

Robert did a series called West Cork Towns and Villages and he wrote about Schull in 2021. (Don’t be confused, by the way, by the fact that the author is given as “Finola” on the top of many of these posts: now that I am the sole administrator of the website, WordPress has automatically assigned all authorship to me and I can’t seem to change it back.) It was during Calves Week in August and Schull was en fete and looking sunny and busy and gorgeous – as it is all summer anyway.

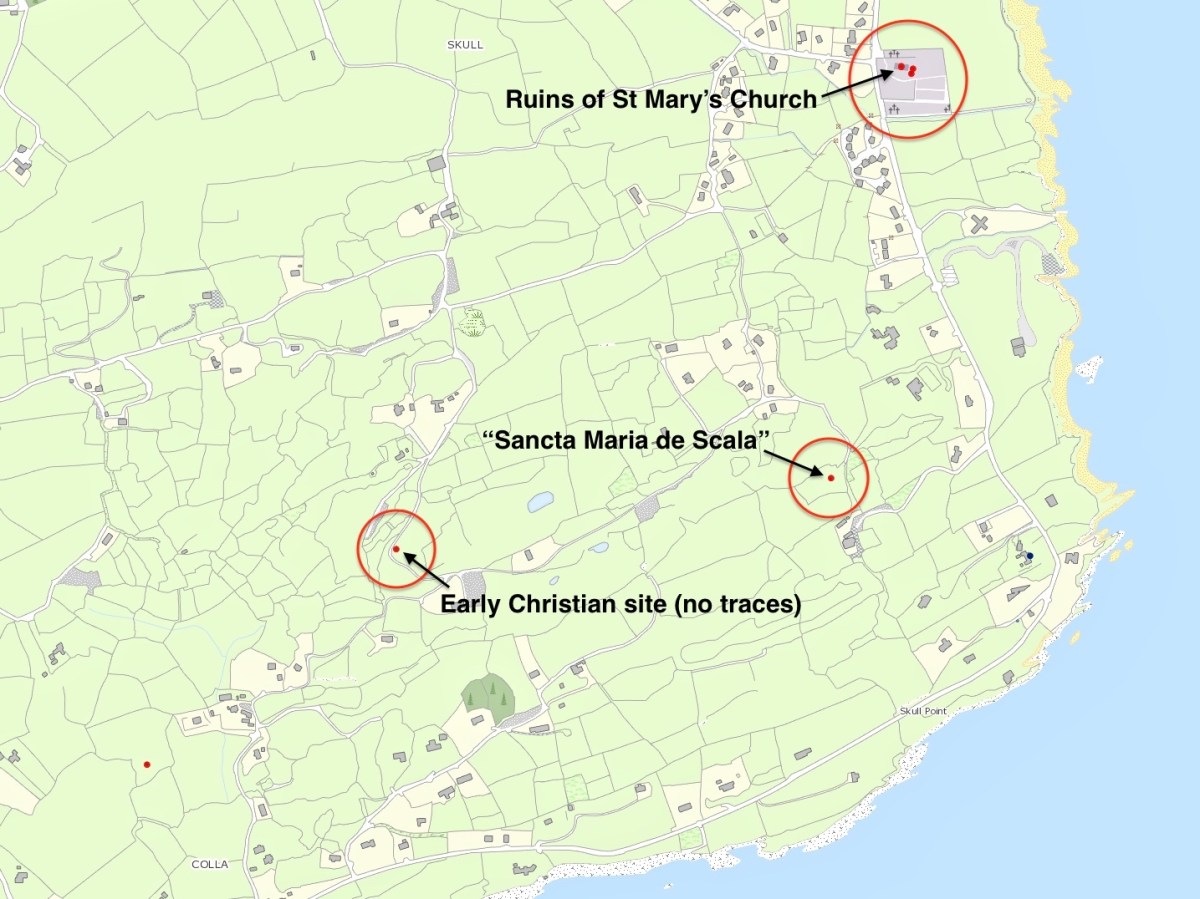

One of the topics Robert tackled was the name – Schull, or Skull as it is invariably given on old maps. In two posts he traced the possibility that somewhere around here was an ancient ecclesiastical settlement named for Mary. In the first one, he referred to the The National Monuments record which states: According to local information, this is the site of Scoil Mhuire or Sancta Maria de Scala, a medieval church and school that gave its name to this townland and to Skull village . . .

In the second, Schull – Delving into History, he charts the various evidence, or mythology, that gave rise to the ‘local information.’ As a corrective, he urged the reader to also look at John D’Altons’s sceptical take on the placename. I also urge you to do so: it’s here.

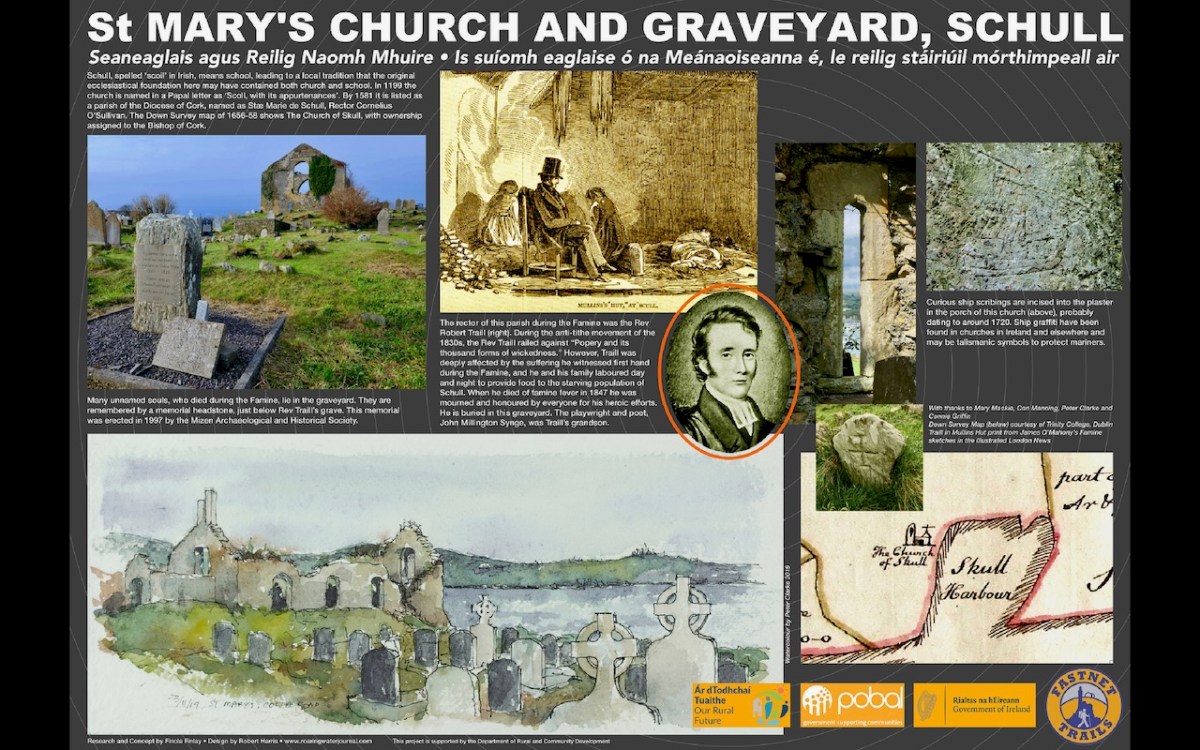

Robert re-visited St Mary’s church in 2022 to write about the ship graffiti in the porch. Subsequently our friend Con Manning wrote an erudite piece for the 2025 Skibbereen Historical Journal on the same graffiti: The ruined church at Schull, Co. Cork, and its ship graffiti

Before we leave St Mary’s I will mention it is the final resting place of many anonymous souls who died during the famine, as well as the Rev Robert Traill, about whom I wrote in my series Saints and Soupers. Traill’s story in Schull started out as that of a typical evangelical clergyman, despising the Catholics and railing against Popery and its thousand forms of wickedness, but ended heroically as he laboured night and day to feed the hungry all around him, dying himself of famine fever. Read more about Traill here and here.

And of course, this is Robert’s final resting place also, with his beautiful hare headstone. I love it that, at the entrance to the Graveyard, is a Fastnet Trails informational board written by me and designed by Robert, about the history of this important place. The watercolour is by Peter Clarke.

Like all the West Cork villages, Schull is also a haven for wildflowers, although you might think they are only weeds. We had a very enjoyable Guerrilla Botany session in early June in 2020 wandering around and chalking in the names of all the plants we found. Time to do that again this spring, I think – who’s up for joining me?

The train used to come to Schull – the Schull and Skibbereen Light Railway came all the way down the Pier and Robert wrote about this rail line in a series of posts. The Schull-related one is here – a set of reminiscences about the stops, the engines, the buildings and the people who made it all run. My personal favourite was Gerry McCarthy who was known as ‘Vanderbilt’ from the careful way he had with money.

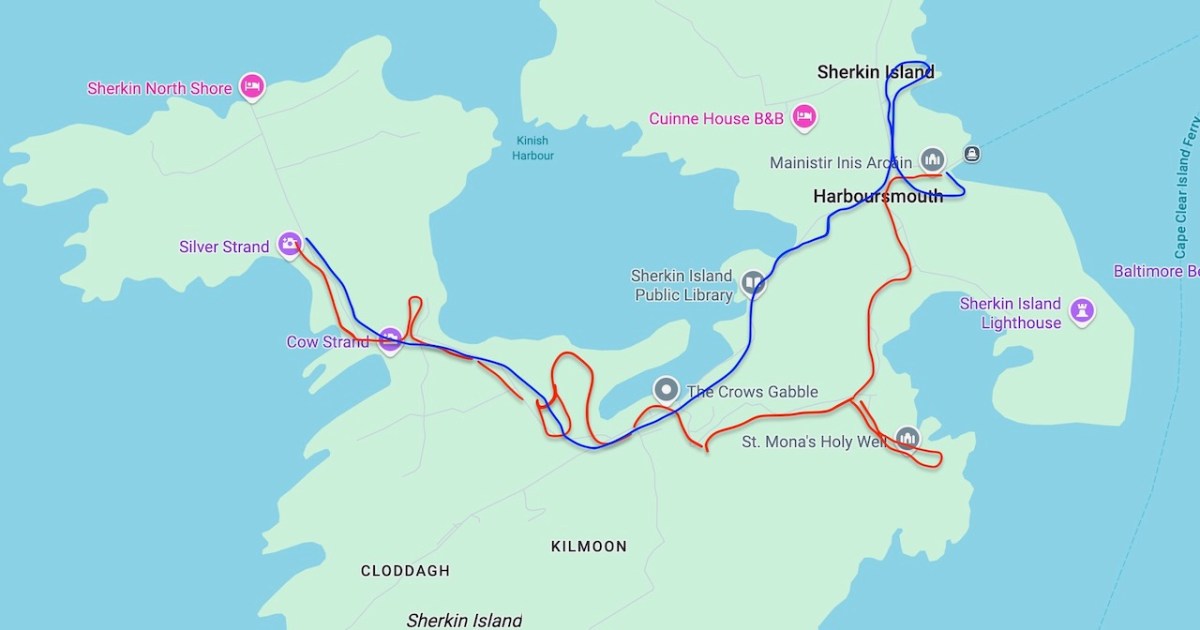

One thing Schull people love to do is walk and there are several lovely walks that start or end right in the village. You can walk from Schull to Castlepoint, or from Rossbrin to Schull. You can do the Butter Road – a green road for much of the way. If you have limited time, you can do the foreshore walk from the Pier out to the graveyard and back (below). Or just keep going out to Colla Pier.

Best of all – you can do Sailor’s Hill, and hope to Catch Connie Griffin so he can explain his stonehenge to you, or lean over the wall and admire Betty’s garden.

Regular service will return soon – I’m already planning my annual Brigid post.